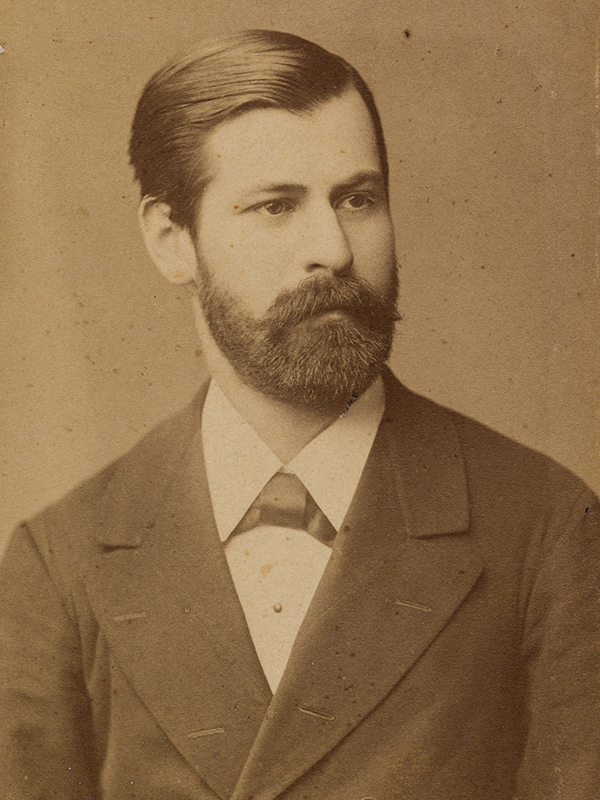

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) was an Austrian neurologist and pioneering figure in the fields of psychology and psychiatry, renowned for his revolutionary theories that reshaped scientific and popular understanding of the human mind. Born in Freiberg, Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic), Freud’s innovative ideas and concepts, such as the interpretation of dreams, the structure of the unconscious mind, and psychosexual development have left an indelible mark on modern psychology and continue to influence the study of human behavior and emotion and the complexities of the psyche.

Sigmund Freud’s early career and his theory regarding the role of child sexual abuse in causing neuroses are crucial aspects of his development as a pioneering figure in the field of psychology. Freud’s ideas evolved significantly over time, and his later work diverged from initial notions. However, too little attention is paid to Freud’s early work and the reasons why he moved away from his theory concerning child sexual abuse during their period. In this brief essay, I explain why. Crucially, it was not because of the rational development of his thought. Rather, it was because of cultural and political pressure he endured in his surroundings and professional life in the late nineteenth century.

In the late nineteenth century, Freud was working as a neurologist and psychiatrist, exploring various topics related to the human mind. In the late 1890s, he began to consider the idea, which he developed from observation of patients under hypnosis, that repressed sexual experiences, particularly those from childhood, might play a significant role in the development of pathology, including neuroses. He theorized that repressed memories could resurface in the form of symptoms of psychological distress. The point of psychoanalysis was to bring these repressed memories to the awareness of the consciousness mind so that the patient could deal with them forthrightly.

Freud’s initial views on the causation of neuroses were centered around child sexual abuse as a potential trigger. In “The Neuro-Psychoses of Defense” (1894), Freud introduces the concept of defense mechanisms as a way individuals protect themselves from distressing thoughts and feelings. This becomes a cornerstone of Freud’s later psychoanalytic theory. However, it is also a key part of his early work on child sexual abuse. In an unpublished manuscript, penned some time around 1895, in what is sometimes referred to as “seduction theory,” Freud considers the possibility that his patients’ accounts of childhood sexual abuse were significant factors in the development of their neuroses. He proposes that experience plays a role in the formation of unconscious conflicts and symptoms.

In his 1896 paper “On the Aetiology of Hysteria,” Freud presents case studies of patients with the condition and proposes that their symptoms might be linked to unresolved sexual experiences from their past. He expresses his belief that patients’ reports of childhood sexual abuse experiences were key factors in understanding their mental health issues. In “Sexuality in the Aetiology of Neuroses” (1898), Freud continues to develop his thoughts on the role of early sexual experiences in the causation of neuroses. He discusses the complex interplay between sexual factors, traumatic events, and psychological symptoms.

These papers were met with skepticism in the psychiatric community. Indeed, his ideas became quite controversial. Obviously, one of the factors that led to the rejection of Freud’s early theory was the prevailing cultural and societal norms of the time. Discussing child sexual abuse was taboo. Freud’s seduction theory challenged these norms and thus were met with resistance from both colleagues and the wider society. He was a young professional and the controversy threatened to derail his career.

At the time, Krafft-Ebing (1840-1902) was an influential Austro-German psychiatrist and pioneering researcher in the field of psychology, renowned for his significant contributions to the study of human sexuality and mental disorders. Krafft-Ebing, who coined the term “sexology” (as well as “sadism” and “masochism”) focused his work on describing various sexual behaviors and paraphilias rather than on the developmental aspects of neuroses. His most famous work is the 1886 Psychopathia Sexualis which established him as the leading expert in the field. Krafft-Ebing shared the overall conservative attitudes of the psychiatric community of that era, which, combined with the societal taboos surrounding sexuality, contributed to Freud’s ideas being met with skepticism and rejection.

Due to the challenges and skepticism he faced regarding his initial theories, Freud underwent a significant reevaluation of his approach. He shifted the focus from external factors, such as childhood sexual abuse, to internal mental dynamics and conflicts. While he initially believed that women suffering from hysteria and neuroses had experienced sexual abuse, he later began to consider that these patients might have developed fantasies in the context of their early sexual development. These fantasies, even if not grounded in real events, could still generate unresolved intrapsychic conflicts. But the idea that they were so grounded faded from his work. This transition marked a pivotal point in Freud’s work, leading to the development of his psychoanalytic theory and its dissemination.

Freud indicated the shift in his thinking in “On the Aetiology of Hysteria.” There he proposed that certain neurotic symptoms in his patients might not necessarily be tied to actual experiences of sexual abuse, but could also be linked to unresolved psychological conflicts, fantasies, and unconscious desires related to sexual development. Freud continued to develop and refine these ideas in subsequent works, such as the 1905 collection of three essays “The Sexual Aberrations,” “Infantile Sexuality,” and “The Transformation of Puberty.” In these essays, he introduces the concept of infantile sexuality and suggests that all humans go through different stages of psychosexual development in childhood. (It is in these essays that Freud theorizes sexuality as a continuum ranging from heterosexuality to homosexuality.)

We now know that as many as one in five individuals worldwide has experienced some form of childhood sexual abuse. This can include a wide range of abuse, from unwanted sexual comments or touching to more severe forms, such as rape. Because childhood sexual abuse is underreported due to factors such as fear, shame, and stigma many cases go undisclosed, leading to an incomplete understanding of the true prevalence. Regardless of prevalence, it is well-established that childhood sexual abuse carries profound and lasting impacts on individuals’ mental, emotional, and physical well-being. These effects may extend into adulthood and may contribute to various psychological and interpersonal difficulties. (See my essay What is Grooming?)

Needlessness to say, on this point, Freud was not a profile in courage. At the same time, as we have seen up close in our own time, the consequences for telling the truth about matters the powers-that-be want people to lie about can be severe. The obvious example is gender ideology. Telling the truth about gender, that there are only two and that humans cannot change their’s (no mammal can), can result in cancellation, demotion, deplatforming, and disciplinary action. Forcing people, especially those who occupy places of authority, as Freud did as a prominent neurologist, to deny the truth and accept an obvious lie is a function of power. Had Freud stuck to his original conclusion that hysteria and neuroses often had child sexual abuse and child sexualization at its core, our understanding of these problems, as well as the problem of grooming, would be much further along. It might have carried a child protective function given Freud’s reputation. Then again, the man might never have had a reputation had he stuck to his guns.

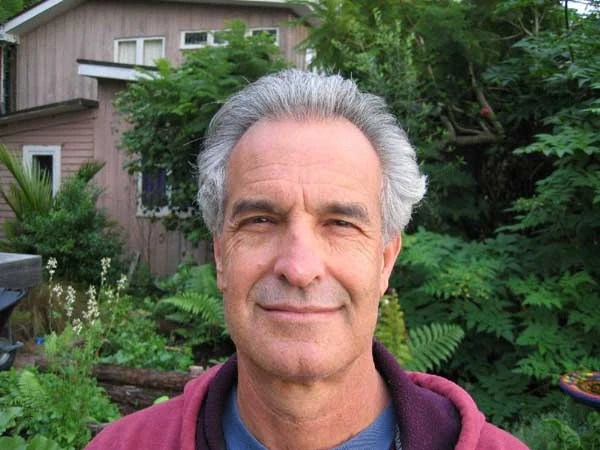

The major work concerning Freud’s and his shift way from his original theory is The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory, penned by psychoanalyst Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson in 1984. Masson had a front row seat to Freud’s transformation, serving as Projects Director at the Sigmund Freud Archives, where he had access to several unpublished letters written by Freud. Masson contends that Freud intentionally withheld his early proposition (seduction theory) that hysteria stems from sexual abuse during childhood. Masson asserts that Freud suppressed the hypothesis due to his reluctance to accept that children could fall victim to sexual violence and abuse within their own families. Masson also argues that Freud worried that his seduction theory would lead to a reluctance in the field to accept his psychoanalytic theory and method. My contention is that Freud’s reluctance was, at least in part, due to his awareness of the consequences for advancing such a claim. Freud was rightly concerned for his career path and reputation.

Masson himself felt cultural and political pressure for his argument. The book was met with unfavorable, even hostile reviews, with several critiques cloaking politics beneath a dismissal of Masson’s interpretation of psychoanalytic history. Within the field, reviewers categorizing the book as the latest installment in a series of assaults on psychoanalysis, emblematic of the prevailing reaction against Freudian. Notably, Masson’s conclusions found support among certain feminists. However, predictably, with the rise of gender ideology, which puts central to its politics the sexualization of children, a movement that has since become embedded in western institutions, Masson’s proposition that children possess inherent innocence and lack of sexuality was especially offensive—and potentially harmful to movement objectives. With child sexualization having become a major part of the sexual revolution, unfolding during the 1960s and 1970s, Masson was perceived as an organic intellectual for the reaction against the sexual revolution that marked the 1980s.

Fascinating.