“In the state of Georgia, Spelman College is a historic Black [sic] college and university, an HBCU. It has no diversity. And by that I mean that all the students at Spelman are women. All of the students at Spelman are African American,” Edward Blum notes in a New York Times interview. “These are African American women that want to go to this college knowing that there is no skin color diversity or sex diversity at their college,” Blum explains. “This is where they want to go.”

Edward Blum is the man who just won just won his case at the Supreme Court against Harvard and the University of North Carolina in a decision that effectively ends affirmative action policies in American college admissions. Blum has been working toward the end of race-based admissions in higher education for years, bringing his first case before the Supreme Court in 2012 with Fisher v. University of Texas. After he lost that case, the 71-year-old legal activist founded a group called Students for Fair Admissions, and tried again. This time he prevailed.

As for Spelman College, so much for diversity. It’s a scam. They’re dividing us by race. Who are those who are dividing us by race? Progressive elites. The Democratic Party. The administrative state. Corporations. Elite institutions cherry pick tribal leaders, token members of recognized and elevated groups the corporate state wishes to pull into the hegemonic political culture to manufacture organic control over society.

It’s obvious that the elite have no interest in pulling into this system poor black and brown people. A system based on social class would result in an overrepresentation of black and brown students at elite colleges and universities. That’s because blacks and brown are overrepresented among the poor. This would raise new problems, to be sure. Poor black and brown students are ill-prepared for the rigors and standards of elite colleges and universities, expectations and criteria that are being watered down or eliminated. But one need not worry about that. Affirmative action was never really based on righting historic wrongs. It followed the abolition of American apartheid for a reason; race-based control over populations is too effective a strategy to relinquish. The elite are interested in the minority children of the professional-managerial strata, especially the offspring of the black intelligentsia. Affirmative action, DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion), the proliferation of ideological degrees, such as African-American studies, and all the rest of it are components of a racial control strategy.

As political scientist Adolph Reed, Jr., put it so well in “Antiracism: A Neoliberal Alternative to a Left,” published the May 2018 issue of Dialectical Anthropology: “At a 1991 conference at the Harvard Law School, where he was a tenured full professor, I heard the late, esteemed legal theorist, Derrick Bell, declare on a panel that blacks had made no progress since 1865. I was startled not least because Bell’s own life, as well as the fact that Harvard’s black law students’ organization put on the conference, so emphatically belied his claim. I have since come to understand that those who make such claims experience no sense of contradiction because the contention that nothing has changed is intended actually as an assertion that racism persists as the most consequential force impeding black Americans’ aspirations, that no matter how successful or financially secure individual black people become, they remain similarly subject to victimization by racism.” Reed charitably adds, “That assertion is not to be taken literally as an empirical claim, even though many advancing it seem earnestly convinced that it is; it is rhetorical. No sane or at all knowledgeable person can believe that black Americans live under the same restricted and perilous conditions now as in 1865.” Obviously.

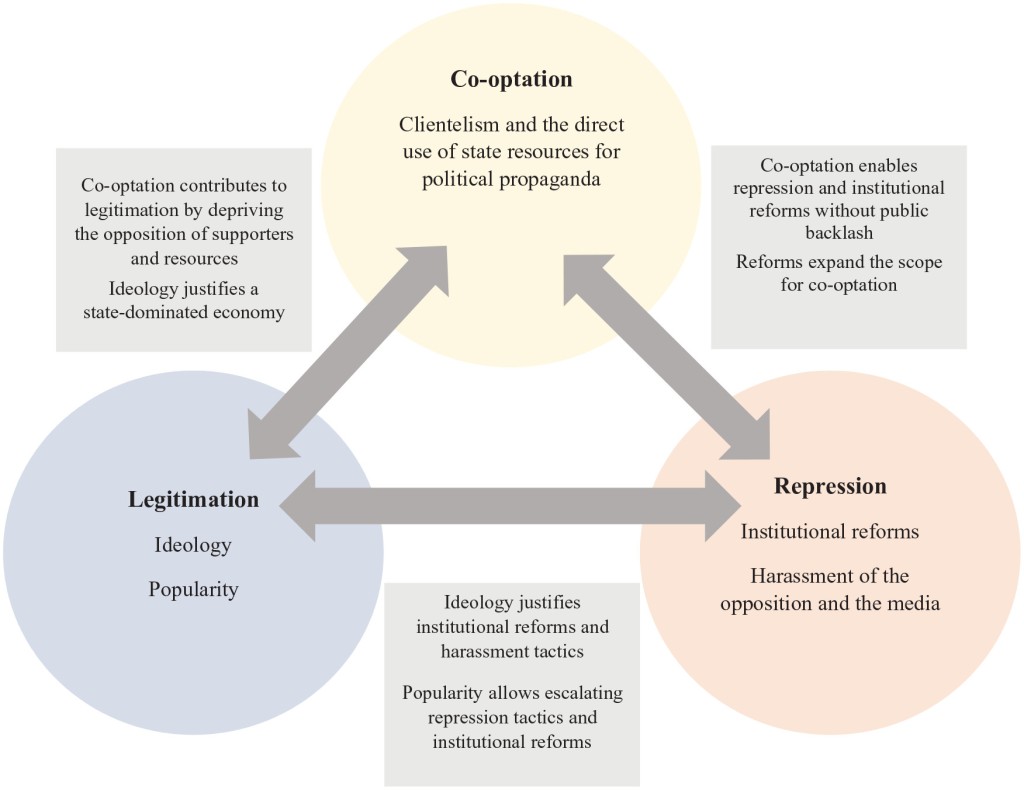

Of course, as Reed points out, things had to have changed for Bell’s rhetoric to have any force. At least some things changed. The need to corporate elites to control the masses did not, and, as noted, racism remains a powerful weapon in the arsenal of control, so the practice of exclusion and subordination to which 1865 brought an end was eventually replaced by a system of patronage and co-optation—after Jim Crow could no longer cling to legitimacy. The new method of race and ethnic control is not new, of course. This is the way hegemony is practiced around the world and has been for thousands of years. This is the work of empire. It signals that what pretends to be the American republic has jettisoned its democratic creed and shifted to a strategy of administrative control and bureaucratic management, a strategy legitimated by a false rhetoric of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

To provide a contemporary third world example of the strategy under analysis, in Jordan, a country in which I spent some time in teaching at the United Nations University (see my lengthy blog entries Journey to Jordan, November 2006 and Journey to Jordan, April 2007), the Jordanian King, Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein, a member of the Hashemite dynasty, the reigning royal family of that country since 1921 (Jordan became a country on May 25, 1946), incorporates influential members of the various tribes that make up Jordanian society into the national leadership structure, which he can then use to exercise indirect control over those populations. One of the values of the historical-comparative method is that it allows the thinker to consider the way control systems work across different cultural and historical contexts.

Despite its degree of modernization (a bicameral parliament consisting of the house of representatives and the senate, with members of the house elected through a mixed electoral system which allows citizens to participate in the political process), Jordan retains significant tribal elements, and tribal affiliations continue to play a role in the social and political fabric of the country. Tribalism has deep historical roots in Jordan, and tribal networks and loyalties influence various aspects of Jordanian society, including economic, political, and social relationships. Tribes in Jordan are organized around kinship ties, with a hierarchical structure and a prominent tribal leader. These tribal affiliations are based on common cultural traditions, land ownership, and shared ancestry. In the political sphere, tribal connections impact electoral dynamics and political representation. Tribal leaders and influential figures play a role in mobilizing support and endorsing political candidates during elections. Political parties in Jordan maintain ties with tribes and seek their support to secure electoral success.

In terms of social relationships, tribal affiliations shape interpersonal networks and influence access to resources and opportunities. Tribal identity carries implications for education, employment, and social mobility, particularly in areas where tribal structures are more prevalent. Not all Jordanians identify strongly with tribal affiliations. Education, modernization, and urbanization, have led to the emergence of more diverse identities and social structures, and many Jordanians prioritize national identity over tribal identity. There are efforts among these groups to foster a more inclusive and equitable society that give the appearance of a desire to transcend tribal divisions. Maintaining tribal society, indeed, reconstructing the tribal system in a way that allows that system to integrate with the Jordanian national identity, again a construct of recent vintage, is a crucial piece of the control structure. Put another way, the detribalizing force of nationalism is strategically restrained in order to maintain a fractured and thereby controllable system of triple affiliations.

The Jordanian government recognizes the significance of tribal affiliations and seeks to maintain a balance between the ancient traditions, however much reconstructed by modernity, and modernization, i.e., capitalism, as an explicit goal of economic and social development. The Jordanian state has established mechanisms to engage tribal leaders and representatives in the political process, aiming to maintain the appearance that the interests and concerns of tribal communities are taken into account in governance and policymaking. Thus the relationship between the monarchy and the tribes involves elements of incorporating tribal leadership into the government to establish national hegemony. The monarchy recognizes the importance of tribal affiliations and seeks to maintain a strong connection with the tribes to ensure their support and to foster national unity and political stability. The Jordanian monarchy has historically relied on tribal alliances and the support of influential tribal leaders to consolidate power and maintain stability. Tribal leaders serve as intermediaries between the monarchy and their respective tribes, helping to mobilize support and maintain order within their tribal communities.

To foster national hegemony and incorporate tribal leadership into the government, the state employs several strategies. Patronage and co-optation is an obvious one. The monarchy includes members of influential tribes in key governmental positions, such as ministerial positions or governorships. This practice helps ensure that tribal interests are represented within the government and allows the monarchy to maintain a broad base of support. Co-optation is institutionalized; the Jordanian political system includes mechanisms for tribal representation in the parliament. The appointed members of the Senate often include representatives from tribal backgrounds, ensuring that tribal perspectives are considered in the legislative process.In a process of consultation and engagement, the king routinely engages with tribal leaders, seeking their input and involving them in decision-making processes—obviously in a controlled way. Consultation gives the appearance that the state is hearing and addressing the concerns and interests of the tribes, enhancing their sense of inclusion and participation in the governance of the country. Addressing concerns of the tribes often involves economic and social development initiatives. The monarchy implements social and economic development projects in tribal areas, aiming to improve education, health care, infrastructure, and job opportunities. These initiatives help to alleviate economic and social disparities and address the needs of tribal communities, fostering a sense of loyalty and support for the monarchy.

I spent some time describing the Jordanian context because understanding that system helps me see how a similar process has marked certain times and places in the United States and, more broadly, the European world-system. Like Jordan, the United States was established in the context of a tribal society. Historically, in the United States, policies of forced assimilation and removal of indigenous populations were implemented, leading to significant hardships for and displacement of American Indian tribes. In recent decades, there have been efforts towards recognition of tribal sovereignty, emphasizing reconciliation and collaboration with indigenous nations. The US government has worked on initiatives like tribal self-governance and resource-sharing agreements to address the concerns and improve the well-being of the tribes. There is a nation-wide push to convey attention to the problems plaguing the American Indians—cultural preservation, educational challenges, health disparities, land and resource rights, socioeconomic inequalities, substance abuse and mental health, violence and crime—with symbolic acknowledgements of the history of colonization and the responsibility of Europeans in creating these problems.

In place of integrating American Indians into the general population, in part because of American Indian resistance to assimilation, a strategy of cooptation of leaders of the various tribes was instituted, with talent cultivated by the government for the purpose of controling Indian lands. This was what Wounded Knee in 1973 was about. The occupation of the town of Wounded Knee, located on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, was a significant event in the American Indian civil rights movement. One of the arguments put forth by American Indian Movement (AIM) leaders during the occupation was that the tribal leadership had been coopted by the federal government. There was widespread dissatisfaction among Indian activists and communities with the perceived lack of autonomy and self-governance within tribal governments. AIM argued that tribal leaders, albeit often elected officials, were nonetheless controlled by federal policies and funding, which they believed undermined the rights and popular interests of the people. AIM leaders, such as Russell Means and Dennis Banks, voiced concerns that tribal leaders had become disconnected from the needs and aspirations of their the people due to their alignment with federal policies. They argued that tribal governments had been coopted by Washington, DC, and were not or could not adequately representing the interests of their communities.

The term scholars use in the field of international political economy and social change and development (one of my areas of specialization in my PhD program) to describe the role the co-opted individuals play is colonial collaborator. This term refers to individuals who or groups that align themselves with or actively collaborate with colonial powers in various capacities. These collaborators play a role in assisting, benefitting from, and supporting the colonial enterprise, often at the expense of their own constituents. Colonial collaborators can be found in different contexts and regions around the world where colonialism takes place. They include local elites, administrators, officials, intermediaries, and individuals seeking personal gain or protection within the colonial system. These collaborators could be from the indigenous population or from other ethnic or social groups.

The motivations for collaboration with colonial powers vary. Some individuals may see collaboration as a means to gain power and privilege and wealth within the colonial system. They may seek personal advancement or protection for themselves or their families. Others may believe that collaboration will accelerate development and modernization of their communities, or lead to improved living conditions. Collaborators are rewarded with positions of authority, such as local leaders, administrators or chiefs, appointed or approved by the colonial authorities—or elected in rigged elections. They act as intermediaries between the colonial powers and the local population, facilitating the implementation of colonial policies, the extraction of resources, and the imposition of control. However, the actions of colonial collaborators, where consciousness exists, which we saw in the case of Wounded Knee, are viewed negatively by their own communities. Colonial collaborators are seen by opponents as betraying the people’s interests, contributing to the marginalization, exploitation, and subjugation of their own culture, land, or resources. Collaborators are viewed as complicit in the perpetuation of colonial rule and as obstructing efforts for liberation and self-determination—again, if enough people have awakened to create a critical mass.

The Black Panthers understood this, as well. Party theoreticians—Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver, Fred Hampton—often talked about how black America are treated very much like the subjects of a colonial power. The relevant concept here is internal colonialism, which refers to a theoretical framework capturing the dynamics of colonial-like relationships within a single country. the concept focuses attention on the ways in which dominant groups or regions within a nation exercise control and exploit other subordinate groups or regions within the same national boundaries. In the context of internal colonialism, the dominant group or region assumes a position of power and even authority, while the subordinate groups or regions experience various forms of marginalization, exploitation, and cultural suppression.

Key characteristics and dynamics of internal colonialism include economic exploitation, cultural suppression and marginalization, political power imbalance, and resource extraction and environmental impacts. The dominant group or region controls and benefits disproportionately from economic resources, industries, and infrastructure, while the subordinate groups or regions face economic disadvantages, limited opportunities, and resource deprivation. This can result in uneven development and persistent economic disparities. Subordinate groups or regions experience cultural suppression, discrimination, and marginalization, as their languages, customs, and identities are devalued or undermined by the dominant group or region. This leads to the erosion of cultural heritage and a loss of self-determination. The dominant group or region possesses greater political power and influence, shaping policies, institutions, and governance structures in ways that reinforce their control. Subordinate groups or regions often face limited representation and voice in decision-making processes, perpetuating power imbalances. The dominant group or region exploit the natural resources within subordinate territories, often resulting in environmental degradation and the displacement of local communities.

In order to apply these insights to the current corporate-capitalist context in the United States, to shift the focus from past colonial relations and, moreover, colonialism as metaphor, to corporate governance and the administrative management of population groups within the modern nation-state, which are the concrete sources of power in the system, one needs to adjust the language only a bit. Moreover, and more importantly, I think, the neo-Marxist critique of the system suffers from the corruption of New Left ideas that comprise an ideology that, with its emphasis on identitarianism, presents itself is divisive ideology that functions to establish a different type of totalitarian control over the population. Indeed, the surface similarities between the New Fascism of the progressive-captured corporate state bureaucracy, on the one hand, and the totalitarianism of state socialism that inspires the anti-imperialist critique, on the other hand, has led folks on both the left and the right to confuse fascism with socialism.

With this in mind, the following is an accurate empirical re-specification: Key characteristics and dynamics of corporate bureaucratic control include economic exploitation, cultural suppression, the marginalization of popular ideas, political power imbalances, and resource extraction and environmental impacts. At the bottom of the system are the proletarian masses. The dominant corporate entities control and benefit disproportionately from monopoly control over economic resources and industries, as well as command of the infrastructure, while the proletarian fractions face economic disadvantage, limited opportunity, and resource deprivation. Class relations are the source of persistent economic disparities. Proletarian fractions see their customs and identities co-opted, debased, devalued, and undermined by corporate power. These processes lead to the erosion of cultural integrity and a loss of self-determination—and class consciousness and effective political organization and mobilization. All of this is disorganizing. Corporations possess greater political power and influence, shaping policies, institutions, and governance structures in ways that reinforce their control. The proletariat faces limited representation and voice in decision-making processes, perpetuating power imbalances.

With the emergence of the corporate state, affirmative action became a progressive tool for managing the class struggle in a way similar to the previous examples—granting the historical particulars of the current situation; to be sure, concrete circumstances are variable, but the dynamics of control are highly similar across their cultural and historical instantiations; variability is explained by the particular challenges faced by actually-existing historical systems. In the US experience, the control system is seen in, among other things, the strategy of multiculturalism established by cosmopolitan elites in the early twentieth century to control urban immigrant populations and to isolate the heartland—Middle America—from decision making. The idea here is to move away from the detribalizing force of nationalism and move the West towards transnationalism via multiculturalism, which back then was called “cultural pluralism,” with culture here understood as ethnic and racial identification. Thus transnationalism is at the same time the re-tribalizing of world society. (See An Architect of Transnationalism: Horace Kallen and the Fetish for Diversity and Inclusion.) Affirmative action followed from the social logic of multiculturalism, wherein race is re-conceptualized as cultural, moved away from its original biological conception. Its recognized incompatibility with the values of individualism and equality inherent in the American Creed provides us with hope that the Creed is still alive.

The paradigm of modern tribal control by the corporate state is command of the black community by the Democratic Party and the administrative state, which is fully captured by progressivism. That this is a form of class control is seen by a cursory examination of the socioeconomic stratification internal to the demographic (this is what Reed is talking about); there is wide variability in wealth and income in the black demographic. Well-off blacks are incorporated into the structure of power through affirmative action and used by elites to indirectly control rank-and-file blacks across the class structure by assuming positions of leadership in education, politics, etc. DEI sustains the tribal arrangements of modern corporate, academic, governmental structuring of power through the distribution of rewards based on tribal identification (race, gender, etc.). The system works to sharply decrease the proportion of the proletariat in the structure of power in order to continue the isolation of middle America from decision making—further delegitimized by manufacturing the falsehood of a white middle America that is racist, nativist, xenophobic, etc.

Black progressives who run the cities are drawn from the well-off ranks of blacks to maintain Democratic Party hegemony over the black populations there—and everywhere. This has resulted in over ninety percent black support for Democrats despite progressive policies keeping blacks in impoverished and crime-ridden circumstances. In fact, it was the Great Society programs that destroyed the black family and permanently ghettoized blacks. Democrats believe this strategy will work with other racial and ethnic groups, which is why they have opened the borders. The trick is to avoid assimilation of immigrants into mainstream American culture. Hence aggressive DEI programs and the praxis of multiculturalism. It’s all very anti-proletariat. While transnationalists offshore production and open the borders to devastate the American working class, which has the greatest negative effects on black and brown people, the same elites elevate token blacks in the system, shifting the perceived locus of oppression from class oppression to identitarian struggles which are manufactured by progressive elites. DEI is a system designed to reify the divisions the corporate state has manufactured. This is why assimilation and integration have become dirty words.

This is, or at least was, the function of affirmative action: to cultivate what Manning Marable called the “black Brahmins” in his book How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America (inspired by How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, a 1972 book written by Walter Rodney that describes how Africa was divided among the colonial powers). Marable empirically examines the role and function of the black underclass, working class, farmers, entrepreneurs, preachers and Brahmins. These different strata and classes have been incorporated into the structure and logic of the corporate state in different ways in order to perpetuate capitalist hegemony.

I want to be careful not to attribute to the late Manning Marable my use of his work in formulating my argument. But I think it does follow from it. Marable draws on the term “Brahmins” from the Indian caste system to highlight the social and economic stratification within the black community. He argues that the black Brahmins represent a privileged segment of the black population that occupies influential positions, including intellectuals, politicians, and professionals. They were often associated with the educated elite and had access to education, resources, and social networks. Marable’s point regarding the black Brahmins is twofold. First, he argues that the existence of this privileged class within the black community obscured the pervasive socio-economic inequalities faced by the majority of blacks. By focusing on the achievements and successes of the black Brahmins, the larger structural issues of economic exploitation is obscured. Secondly, Marable critiques the political and ideological tendencies of the black Brahmins, who he argues align themselves with the interests of white elites and neglect the needs and aspirations of the broader black working class. This alignment, according to Marable, served to reinforce the existing power structures and hindered the progress of black workers.

So affirmative action is gone. At least we hope so. But affirmative action was just one string of a web of race-based control strategies deployed by the corporate state to keep the proletariat in a state of perpetual disarray marked by invented and exaggerated antagonisms and resentments. Curricula founded upon critical race theory (CRT), DEI programming, multicultural policies—the web is an intricate one and teasing it apart will not as easy as saving Delambre-fly from the spider by crushing them both with a stone. From the New York Times article that started us off: “Now, with a legal victory in hand, Mr. Blum is thinking about what’s next in his work to remove the consideration of race from other parts of American life and law. In a wide-ranging discussion, he told me about how he’ll be watching to make sure elite institutions of higher learning abide by the court’s recent decision, and why he thinks corporate America will be facing scrutiny next.” Indeed. This is the location where we must now move our struggle.