Recently I organized a session at the 2020 Mid-South Sociological Association Meetings, held virtually: Contemporary Penology: Thinking About Transformation of Systems and Persons. I am Associate Professor in the Democracy and Justice Studies program at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay where I teach mostly on matters of criminology and criminal justice. My paper was titled “Rehabilitation in the Norwegian Correctional System,” and I want to present the textual basis for my talk. Here is The FAR Podcast covering the talk:

I am on sabbatical conducting a crossnational comparative study of the character and efficacy of various correctional approaches in the reduction of criminal recidivism for a range of purposes: providing scholars and practitioners with detailed and focused knowledge on advancements in penology; developing programs for students studying and preparing for careers in the fields of criminology and criminal justice administration; and making available to the public sound information and methods appropriate to the development and implementation of policies conducive to building inclusive, safe, and just communities. In this talk I discussed is an evaluation, very much in development, of US-style penology in light of the innovative approach of Norwegian penology, with some attention paid to the Swedish situation as a near comparison. This text is the rough sketch of a paper, which I am working up for publication.

A little bit of background. I traveled to Norway and Sweden in the summer of 2018 to gain access to educational and correctional institutions in the cities of Oslo, Stockholm, and Göteborg. In Norway, I traveled to the University College of Norwegian Correctional Service (KRUS), or Kriminalomsorgen, in Lillestrøm, outside of Oslo. My trip to Stockholm involved meetings with researchers at the Swedish Prison and Probation Service (SPPS), or Kriminalvården, in Liljeholmen, a district in the Stockholm archipelago.

In the fall of that year, I was invited by Sociology and Work Science to come to the University of Göteborg for my sabbatical semester. They agreed to host my visit and provide me with office space. In June 2019, I was awarded a sabbatical for fall 2020 to travel to Norway and Sweden to continue my research. Unfortunately SARS-CoV-2 emerged in early spring of this year and my university cancelled all international travel until at least the end of the year. My research continues, but under obviously constrained conditions.

In his landmark 1940 work, The Prison Community, Donald Clemmer coins the term “prisonization,” which he defines as “the taking on” by inmates “of the folkways, mores, customs, and general culture of the penitentiary” (270). According to Clemmer, the phenomenon plays a critical role in determining the success of rehabilitation. The acquired habits of institutional life replace the inmate’s prior sensibilities to the detriment of reformation. “The net results of the process,” Stanton Wheeler writes in his 1961 American Sociological Review article “Socialization in Correctional Communities,” is “the internalization of a criminal outlook, leaving the ‘prisonized’ individual relatively immune to the influences of a conventional value system” (697).

While Clemmer identifies several structural elements shaping prison society, including the antagonistic relationship between correctional officers and inmates, cliques and gangs, and prisoner demography (age, ethnicity, race, and so forth), he is concerned primarily with detailing the dynamics and results of prisonization, not with the origins of the “convict code,” that is the system of sanctions (McCorkle and Korn 1962), or the structural features underpinning it. Clemmer’s insights provoked the development of a large body of literature on prison culture and socialization, the findings of which have generally supported his thesis that imprisoned individuals are at risk in time to acquire the prevailing role-specific beliefs, norms, and values of the institution, and, crucially, adumbrated the institutional logic that gives rise to the dynamic.

Many observers root prisonization to the austere realities of incarceration. Like concentration camps, military service, and psychiatric facilities, the penitentiary is a manifestation of what Erving Goffman described in his 1961 Asylums as “total institutions,” sites where all life unfolds according to externally imposed inelastic rules and schedules. Responsibility for decision-making largely removed from his purview, the inmate finds himself fundamentally reliant upon the penitentiary routine, which is markedly different from the outside world. Goffman argues that total institutions produce a “self-mortification” that sharply limits personal autonomy and stamps the inmate with a new identity. Ann Cordilia’s 1983 The making of an inmate: Prisons as a way of life characterizes this as a form of “desocialization.” We might say that prisoners are resocialized and new loyalties and solidarity relations emerge.

Prisonization is a species of institutionalization, specifically assimilation or integration with inmate culture, what Gresham Sykes (1958) characterizes as “a society of captives.” It’s Sykes’ catalog of the “pains of imprisonment” that informs the conceptual model used in this paper. Sykes identifies five deprivations underpinning inmate adaptation to prison life, deprivations of autonomy, goods and services, heterosexual relationships, liberty, and security. This is commonly known as the “deprivation thesis.” Those things prison deprives are understood as human needs that inmate culture ameliorates, corrupts, or serves.

In his landmark 1958 work, Gresham Sykes characterizes prison as “a society of captives.” His catalog of the “pains of imprisonment” informs the conceptual model used in this paper. Sykes identifies five deprivations underpinning inmate adaptation to prison life: deprivations of autonomy, goods and services, heterosexual relationships, liberty, and security. I will come to those in a moment. Sykes also explores in The Society of Captives the question of power, which he believes is not naked in the penitentiary setting but based on legitimacy. In other words, power as authority. This is arguably true in any complex real-world relationship. According to Sykes’ thesis, what he calls the “the defects of total power,” power involves a twin dynamic of (a) inner moral compulsion to obey by those who are controlled and (b) the legitimate effort or right to exercise control. Control over coercive machinery is not enough to control a society of captives. Although correctional officials are vested with the power to demand compliance from prisoners, their power is in actuality limited and depends to a very real degree on inmate cooperation. It is not possible day-to-day for correctional officials to coerce prisoners into compliance. This suggests that correctional officials can leverage recipricol social relations in the rehabilitative process. Prisons are a community, as Clemmer noted, but a community built upon power asymmetries. This is where degradation and abuses come in.

In James Austin and John Irwin 2001 It’s about time: America’s incarceration binge report affective dimensions to Gresham’s pains, finding among inmates’ feelings of alienation, detachment, meaninglessness, normlessness, and powerlessness. From Austin and Irwin’s perspective, the culture of penitentiaries in which inmates are socialized is caused by their anomic state of existence, as inmates, struggling to make sense of their world, develop their own normative and value systems. The general hypothesis is that empirical research should find a negative relationship between degree of prisonization and the success of rehabilitation but also the presence or absence of pains. Thus, the deleterious effects of imprisonment on life beyond prison depend on the frequency and intensity of association with other inmates, the length of time spent in penitentiary settings, and the character of the prison experience. Putting the matter simply, the more time inmates spend with other prisoners, and the longer their sentences, the more prisonized they will become. But it also depends on the pains of imprisonment—that is, which deprivations are present and in what degree.

Presently, the US incarcerates more persons than any other country and has the highest incarceration rate in the world (see chart below). According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, there were 2.09 million persons in state and federal prisons, jails, and juvenile correctional facilities (738,400 in jails, 1,176,400 in state prisons, and 179,200 in federal prisons), with an incarceration rate of 639 per 100,000 residents. Nearly ten percent of prisoners are female. The US carceral system is notable for significant class, ethnic, and racial disparities, which largely reflect the demographics of crime commission using the categories from the Uniform Crime Report.

The United States overall has a poor record of rehabilitating those it incarcerates (there is wide variations among the states). According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, recent data show that 68% percent of those released from prison in 2005 were rearrested within three years of their release. This rises to 83% in nine years. This measure of recidivism is a rough but useful indicator of the problem of reoffending after leaving custodial supervision. The United States is well-known among advanced democracies for its punitive approach to corrections, policies guided by deterrence theory. The typical punishment regime in the United States emphasizes harsh and degrading conditions.

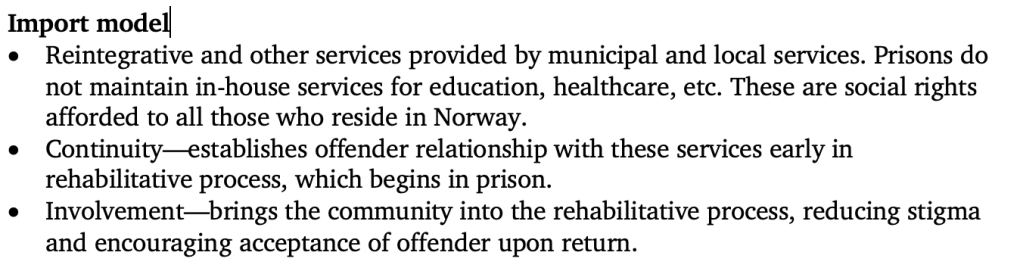

During approximately the same period, according to the World Prison Brief published by the Institute for Criminal Policy Research, prison population in Norway in 2020 stood at 2,653 in 34 correctional facilities, with a rate of 49 per 100,000. Just over six percent are women (see chart below). Twenty-nine percent of prisoners are foreign born. Evidence presented by the Norwegian government indicates that 20 percent prisoners in Norway are recidivists. Correctional institutions in Norway are 73 prercent of capacity.

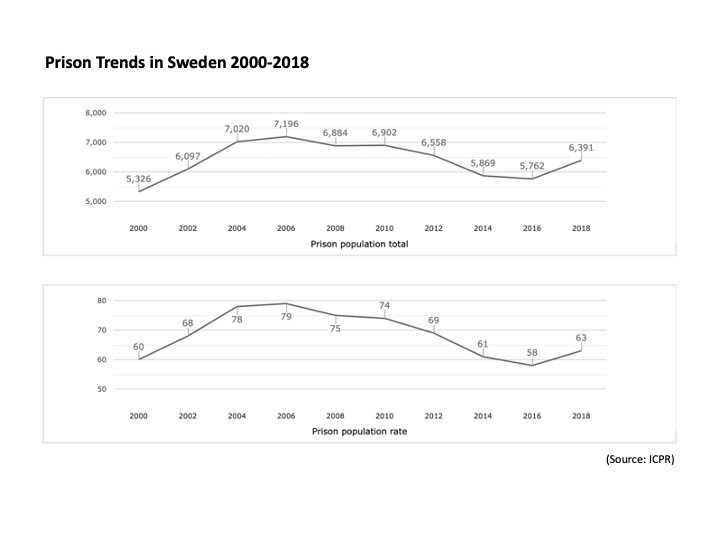

According to the same source, inmates in Swedish correctional facilities in 2020 numbered around 7,000 in 79 correctional institutions, with a rate of 68 per 100,000 (see chart below). Just over six percent are women. Just over 22.1 percent are foreign born. Recidivism rates, at around 40 percent within three years, are lower in Sweden than in the United States but considerably higher than in Norway. Sweden’s correctional system is 101.6 percent capacity.

When I began my project, the evidence indicated that prison populations were rising in Norway while falling in Sweden. Norway was on a get-tough-on-crime kick, while Sweden was in a period of lienency. However, since 2016, the respective trends have reversed in each country. I want to explain this in the following manner, and this is based on other work that I am doing on the political economy of penal institutions and political-sociological trends in these three countries.

Reduction in the size of the penitentiary in the United States is a function of historically low rates of crime and especially violence in the United States. The country has seen significant reforms over the last few years, but we likely won’t see the results of that, all things being equal, for a few years now. Why crime has fallen is beyond the scope of my talk today.

While crime has declined in the United States over the last several years, it has increased in Norway and Sweden. There are complex reasons for this, but what is relevant here is that the two countries have responded to the crime increase very differently. Until recently, while Sweden did not move aggressively to control crime through the traditional means of criminal justice, Norway, on the other hand, did. This has a great deal to do with the politics, with Norway having moved substantially to the right politically over the last 15 or so years, while Sweden has kept its more progressive attitudes. This changed over the last few years. We now see prison populations rising in Sweden while falling in Norway.

One might be inclined to credit the downward trends in Norway to the deterrent effect of a more aggressive Norwegian response, which involves a major shift in the focus of crime control to more serious criminal offenses. To be sure, deterrence probably explains some if not much of it. However, at the same time, Norway endeavored to become a model of rehabilitation in order to reduce recidivism, which its penologists agreed would further enhance public safety and reduce the size of the prison population. While Sweden prisons are now at capacity, Norway’s prisons have gone from overcrowded to three-quarters capacity.

A big piece of understanding the Norwegian system is understanding what Norway calls the “principle of normality.” The normality principle limits punishment to restriction of liberty only. No other rights are explicitly compromised by the sentencing court. Punishments are designed so that no one will exist in stricter circumstances than necessary for the sake of the community, a principle that emphasizes placement in the lowest possible security regimes. Life inside prison is to resemble, as much as possible, life outside prison.

When in Norway, I toured the services and shown a cluster of prison cells where correctional workers are trained. Prisoner cells have a living space with a bed, bookshelves, desk and chair, television, and private bathroom with a toilet, sink, and shower. When we asked about the efficacy of various alternatives, the explanation is that alternatives are ordered as a progression that is part of an overall process of rehabilitation. By the time they are freed from the system, they require no more engagement with the system (unless they reoffend).

The Nordic model is focused on preparing inmates for successful reintegration with society after release by focusing on individual variability or within-subject change and the needs of people in the greater society. Norway is especially known for an emphasis on restorative justice, an approach that seeks to repair the harm caused by the offense rather than punish the perpetrator. Restorative justice puts victims, offenders, and community members in charge of determining harm done, the needs of those involved, and ways the damage may be repaired. Moreover, Norway and Sweden stress the importance of avoiding isolating prisoners in order to prevent the phenomenon of prisonization, a type of institutionalization that makes it difficult for ex-convicts to transition to life outside of custodial care.

A very good documentary is Breaking the Cycle, directed by Tomas Lidh and John Stark, concerning Halden Prison in Norway. They compare to Attica Correctional Faculities in Wyoming County, New York. They also show North Dakota State Penitentiary which is taking the inititative to build a more efficacious rehabilitation experience.