Thomas B. Edsall, in an opinion piece, “How Racist Is Trump’s Republican Party?” published in the March 18, 2020 edition of The New York Times, concludes that “there is a large divide not only over the definition of racism, but also over the level of racism in the nation.” Edsall does not provide a direct answer to the question posed in the title of his essay, but rather implies one in course of reaching his conclusion. His essay provides yet another example of how academia participates in the depoliticization of a new type of racism, one that insinuates racism where racism isn’t and identifies supposed perpetrators on the basis of race.

“What this boils down to is that racism is detected, determined and observed through partisan and ideological lenses.” Edsall writes. “This is hardly shocking. Yet what is still quite striking is how much the perception of the importance of racism has changed in recent years.” This could be the starting point for a useful essay on how the perception of racism has shifted from race prejudice and the imposition of legal structures rooted in it or the violation of laws against it (discrimination on this basis) to the characterization of nationalism, populism, and group-based disparities as racist in essence, as well as the assumption of concrete individuals into abstract demographic categories—and then rendering a judgment. In this critique, I will repurpose Edsall’s piece for this end.

Without any critical interrogation of the way in which the perception of widespread racism has been ramped up in the wake of a historic movement that not only dismantled Jim Crow and criminalized discrimination against non-white and non-Asian persons, but also established a system of positive discrimination (affirmative action) providing opportunities for non-white and non-Asians not available to whites and Asians, amounting to, in essence, reparations paid for by generations of Americans who cannot be tied to racial inequities, Edsall implies his opinion (that the Republican Party is racist) by leaving the definition of racism and the degree of racism in American subject to “partisan and ideological lenses.”

This obscurantism is irresponsible for a man who has been reporting on city and national politics since 1967, when he started as a reporter at the Baltimore Sun, before moving to The Washington Post in 1981-2006, and then on to The New York Times where he writes opinion. His experience as a student at Brown University and Boston College over the first half of the 1960s must also be considered here. Edsall is a witness to the radical transformation of American race relations that occurred during that period—a ring-side seat. How could such a transformation escape his ability to make an opinion? From this privilege purchase he could have described the shift from the old civil rights struggle to dismantle the racial hierarchy and establish equality under the law for every person to a post-civil rights movement to reorder the racial hierarchy by defining everything post-structuralist identitarian terms, a movement organized by progressives.

Edsall’s essay starts off on shaky legs, taking as its theme Stuart Stevens’ claim that the Republican Party is the “white grievance party.” Stevens, for those of you don’t know, was the lead campaign strategist for George W. Bush’s 2000 and 2004 elections, elections that saw the return to power of the Cold War liberal and the affirmation of neoconservative policy, a policy that took us into wars in the Middle East and Central Asia. Stevens makes this claim in his forthcoming book It Was All A Lie, which concludes that Republicans turned racist with Barry Goldwater. Stevens tells Edsall that “race is the original sin of the modern Republican Party.” Social justice warriors will find that conclusion grossly inadequate. Race is the original sin of the United States of America, in their view—indeed, race is the original sin of all white people. With this view in mind, a myriad of grievance parties has emerged, animated by the gospel of “intersectionality,” an oppression olympics that identifies whites, especially white males, as the common oppressor. This is is a movement that transforms egalitarianism in oppression.

But Stevens is a way into a discussion that allows Edsall to associate Trump and Republicans with racism. He must do this because he only a few short months ago advised Democrats to eschew political correctness and seek moderation in a piece published in The New York Times, “Democrats Can Still Seize the Center,” on November 1, 2019. There he argued that “President Trump is unpopular, but that doesn’t mean defeating him is going to be easy. Democrats will have to tackle issues that may alienate—and even give offense to—progressives, women, Latinos and African-Americans.” He continues, “Putting together a broad enough coalition to finish the job—to win 270 Electoral College votes—will require navigating fraught cultural arenas: race, immigration and women’s rights—while dodging the broadly loathed set of prohibitions that many voters, including many Democrats, file under the phrase ‘political correctness.’”

In that November piece, Edsall cites the work of Matt Grossman, a political scientist at Michigan State, who found, in a essay published at the Nikanen Center, “Racial Attitudes and Political Correctness in the 2016 Presidential Election,” that “[m]any people dislike group-based claims of structural disadvantage and the norms obligating their public recognition. Those voters saw Trump as their champion. The 2016 election produced greater candidate and voter division around the celebration of diversity and accepted explanations for group disparities.” This fact has not gone unnoticed by political strategists. For example, it led John Feehery, a Republican lobbyist, to suggest that, if they want to win, Democrats “drop the elitist attitude that currently suffuses the Democratic Party which has morphed into an insufferable army of virtue-signaling know-it-all’s who spend all of their time looking down their noses at the unwashed masses in flyover country. It has less to do with specific issues and more to do with the unbridled arrogance that is currently deeply embedded in the DNA of the once great Democratic Party.”

However, Edsall points out that the Democratic Party is no longer the party that enjoyed significant participation from blue-collar workers. Based on polling of Democratic primary voters in 2008 and 2016, the party now tilts toward minorities and well-educated whites. This demographic shift is associated with a shift in the proportion of those in the party who identified as conservatives or moderates towards those who identified as very liberal. In its efforts to weave together a multicultural coalition, which mirrors the public relations of the modern-day corporation and university with their emphasis on “diversity and inclusion,” the Democratic Party has marginalized working class Americans, whom progressives portray as disgruntled and reactionary white men. Edsall’s concern a year out from the general election is that centrism is troubled by primary voters who want a liberal candidate (liberal here meaning progressive). This does not reflect the general election. Edsall must surely be happy with where Joe Biden is at present. So the essay at hand appears meant to raise the racism specter on the other side without triggering those who Grossman found to “dislike group-based claims of structural disadvantage and the norms obligating their public recognition.”

In his latest essay, after introducing Stevens’ thesis, Edsall shifts to a discussion problematizing the definition and conceptualization of racism. Edsall starts with an actual definition by quoting Darren Davis, a political scientist at Notre Dame. Davis is co-author of “Reexamining Racial Resentment,” published in 2011. Davis: “I define racism as an attitude or a belief that stems from hatred or anti-black affect,” writes Davis. “Therefore, a racist is a person who is motivated by hatred or beliefs about the inferiority of African Americans.” Edsall next quotes Chloe Thurston, a political scientist at Northwestern, who argues that “racism, very loosely defined, is an ideology whereby racial groups are organized according to a hierarchy, and members of these groups are often thought to have immutable traits based on their group membership.” This is not very loosely defined, actually. It’s pretty tight, in line with the definition I have developed: racism is an ideology holding that the human population can be meaningful subdivided into categories differentiated by superficial phenotypic characteristics that predict abstractly cognitive ability, behavioral proclivities, and moral sensibilities. (Obviously, race realists would disagree. But the concept of race has been thoroughly debunked. See my Freedom and Reason podcast on this topic below. See also “Race, Ethnicity, Religion, and the Problem of Conceptual Conflation and Inflation” for more details.)

Erick Kaufmann, to whom Edsall next turns, presents a four-fold definition: “Attitudes or behavior that assert that one race is superior to another, or that is intended to promote fear, anger or hatred toward a racial group.” This is well put and uncontroversial. “Favoritism that results in denial of equal treatment under the law to people with regard to race.” A matter of established law. “Race essentialism: the belief that races have biologically sharp boundaries; a belief in racial purity.” (See the various sources above.) Finally, structural racism. This is “institutional practices put in place for racist reasons which have not been modified,” also “where non-racist people behave in a racist way to fit into an institutional norm/peer pressure which applauds racism.”

Kaufmann is a political scientist at the University of London and author of Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration, and the Future of White Majorities (2019). He insists that racism must “be defined rigorously.” The first three folds of his definition are consistent with the way “racism” and “racialism” were defined and understood when coined in the first decade of twentieth century. The fourth fold conceptualizes the world as fundamentally shaped by abstract social forces that concrete persons animate. Individuals are personifications of general categories. This is a sociological view and it demands a lot of those who claim it.

Edsall picks up on the shift and pivots on Kaufmann’s fourth fold. He cites Lafleur Stevens-Dougan, a political science at Princeton, who, in an email, tells him that America (and presumably the trans-Atlantic community) has “baked racism into our political institutions and economic systems.” She argues that if the answer to why black and Latino neighborhoods struggle with poor schools and high crime rates, is that blacks and Latinos are “less smart, less hardworking, or less disciplined,” and so on, then the answer is “racist.” This would be racist if the claim were that blacks or Latinos (an ethnicity not a race, but let’s put that aside for the moment) were all these things because they were racially inferior to whites or other races who do not have these struggles. But these struggles could result from cultural forces. Culture is not race. Culture is a set of attitudes, beliefs, customs, habits, and values. Race is a creature of racism, which I have defined above.

The difference between culture and race is crucial to grasp. Culture is a shared set of instructions for navigating daily life, for finding meaning in one’s existence, and for organizing social roles. Poor whites struggle with poor schools and high crime rates, too. In fact, in concrete numbers, there are many more of them than there are poor blacks. Is it racist to suggest that culture plays some role in determining the situation of whites? I think most of us would agree that it isn’t. Of course, those of us who study poverty know that it isn’t nearly a complete theorization of situation, either. Poverty, black and white, is substantially a consequence of capitalism. So why is it automatically racism if the poor person is black? As I have argued on this blog, because it obscures class relations. This is the function of progressivism: to normalize corporate capitalism.

The point of Edsall’s pivot becomes clear when he turns to this question, which he puts to Davis: would he find racist Asian-American protests of “the potential elimination of entrance exams as the sole determinant of entry into selective high schools”? He asked Davis several questions along these lines: Is “the opposition of well off suburbanites to affordable housing in their neighborhoods racist? Is the number of African-Americans in prison evidence of racism? And is white opposition to the decarceration moment or the prison abolition movement racist?” Davis answers that “not all racialized behavior and expressions stem from racial hatred or hating African Americans.” However, people, “without being racists themselves, may do and say things that are consistent with a racist ideology.” In the example of Asian-American protests, he does not believe they are racist because there are other motivations beyond “just beliefs about the inferiority of others.” What Davis is pointing out here is why it is so important to retain the standard definition of racism. Defining racism as things that lack racist motivation makes it impossible to oppose these things without appearing to be a racist. Racism becomes a smear used by those who lacks the consideration and patience for making actual argument, a tactic to delegitimize oppositional arguments.

Yet, surprisingly, Davis draws the opposite conclusion. “My overall point is that we have forgotten what racism means,” he tells Edsall. “In doing so, we have focused attention on bigots and white nationalists and not held ordinary citizens accountable for beliefs that achieve the same ends.” But would that not involve holding ordinary citizens responsible for racist acts that had no racist motivation? Moreover, holding them collectively responsible? Edsall buttresses Davis’ conclusion by suggesting that immigration restrictionists concerned with backgrounds stubborn to assimilation are racist in effect. But, once again, culture is not race. Finding some cultural systems stubborn or undesirable is not necessarily a racist argument. Furthermore, one can be an immigration restrictionist on economic grounds, for example in defending the livelihoods of citizen workers against foreign competition, and still have that position characterized as advocacy consistent with the ends racists seek. That makes workers trying to find and keep jobs complicit in racism because supporting restrictions on immigration is by definition racism. Thus is absurd. It puts people in a no-win situation. Thurston expands on this view. “People can participate in and perpetuate racist systems without necessarily subscribing to those beliefs,” she argues. “People can recognize something they participate in or contribute to as racist but decide it’s not disqualifying. And people can design racist policies and systems. These are distinctive manifestations of racism but not all of them require us to know whether a person is expressly motivated by racism.” Rather than meeting the burden of proof that comes with making the accusation, the logic here is that situations so defined are by definition racist.

This is critical race theory. This is not social science, but ideology, the (il)logic foundational to identity politics. The (il)logic shifts principle, from assigning the burden of proof to the party making an accusation, while presuming the accused is innocent of the charge, what critical race theorists call the “perpetrators perspective,” to a prima facie assertion of injustice presumed inherent in inequitable conditions with a guilty party assumed. This is called the “victim’s perspective” in this standpoint. Questioning whether the accuser is a victim becomes “victim blaming.” Victim blaming is racist. (See my essay “Committing the Crime it Condemns” for more discussion of this.)

His sense of charity in gear (or perhaps strategically), Edsall provides a nice counter view from Cindy Kam, a political scientist at Vanderbilt. In an argument consonant with Randall Kennedy’s essay “The Boundaries of Race,” published in the Harvard Law Review (which I summarize in the essay “Race and Democracy”), Kam writes that, as a social scientist, she would entertain a variety of other motivations, including economic consideration, self-interest, and values, such as commitment to a free market, that shape a person’s attitudes and decisions. Examples of the latter are the cases of Milton Friedman and Barry Goldwater with respect to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which both opposed on the grounds of the rights of businessmen. She “would hesitate to label an action as ‘racist’,” she tells Edsall “unless racial considerations seem to be the only or the massively determinative consideration at play, based upon statistical modeling or carefully calibrated experiments.”

The debate over Barry Goldwater’s racism illustrates the controversy and challenges Stevens’ claim that the Republican Party’s racism starts there. Martin Luther King Jr. said that although he did not consider Goldwater a racist, but that the Senator “articulates a philosophy which gives aid and comfort to the racists.” This is Thurston’s view. Roy Wilkins, executive director of the NAACP, agreed. “Senator Goldwater himself is not regarded as a racist in their minds” he said, referring to black Americans, “but they note with dismay that among his supporters are some of the most outspoken racists in America.” Wilkins clarified: “Their quarrel with the Senator lies in their opinion that the federal government must act to protect the rights of citizens against infringement by the states, and the Senator’s belief that the federal government has no such rule.”

Kaufmann’s views are useful not only for Edsall’s recent essay, but could have been used in Edsall’s November 2019 essay. Kaufmann expresses concern over using the racist label others have worried about. He worries that “fear of being labeled racist may be pushing left parties toward immigration policies, or policies on affirmative action, reparations, etc., that make them unelectable.” He is also concerned that “overuse of the word ‘racist’ may lead to a ‘cry wolf’ effect whereby real racists can hide due to exhaustion of public with norm over-policing.” This phrase “real racists” sticks out in the piece. Indeed, Edsall writes, “[n]one of the examples I cited, in Kaufmann’s view, ‘are racist’ unless it could be explicitly demonstrated ‘in a survey that those espousing the policies were mainly motivated by racism.’ If not, he said, the ‘principle of charity should apply.’” I won’t hide this from the reader. I agree with Kaufmann in this debate on this point (I do not agree with Kaufmann when he characterizes antipathy towards Mexicans or Muslims as “racist.” Nor do I find his overall approach, which roots in psychology, to be the most useful way to approach these questions.)

LaFleur Stephens-Dougan does not share this view. “In all the examples you have provided [speaking to Edsall], communities are marshaling their resources to exclude other Americans, who are disproportionately black and brown.” She sees this as racist action. This is a familiar refrain in the immigration debate. However, this view ignores the fact that American communities have been resistant to marshaling resources to those of European descent or supporting immigrations from European countries. These populations are not racialized (see my “Race, Ethnicity, Religion, and the Problem of Conceptual Conflation and Inflation”). Since it would make no sense to claim this was racism, it makes no sense to assume racism in the other cases. These are cultural prejudices and self-interested economic choices.

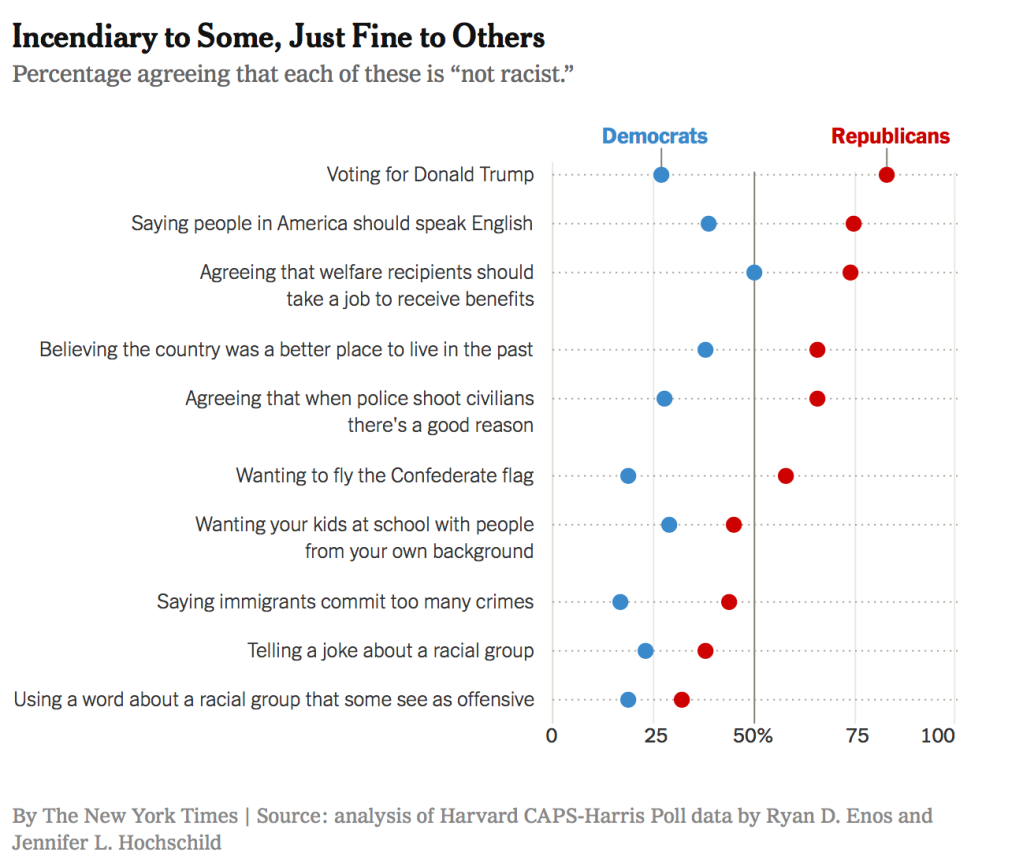

Satisfied that The NYTimes reader has a definition of racism that is useful to him, Edsall turns to the question of the popular definition racism held by partisans of the two-party system. Edsall cites a 2017 survey of 2,296 American adults to rank on a five-point scale ranging from racist to not racist ten statements (see below). The results show that Republicans have a better grasp of racism than do Democrats by a substantial margin. A majority of Democrats see racism everywhere. At the same time, Republicans consider things racist that have nothing to do with race, demonstrating the creep of the post-civil rights redefinition of racism.