The fetish for expertise in narrow disciplinary scientific divisioning, a fragmented knowledge system that appears totalistic, reflects a desire for a priesthood (The Cynical Appeal to Expertise). For this is a chief marker of scientism. Scientism is not be confused with science. I write in my previous blog (Biden’s Biofascist Regime), “Science is comprised of rigorous methods of producing knowledge that proceeds objectively in the context of free and open inquiry. Scientism, in contrast, is an ideology that pulls about itself scientific jargon to conceal its quasi-religious spirit.” Scientism does not tolerate criticism of its “findings.” It relies on state power and corporate governance to establish its conclusions as official truth. I further write, “We see this in the manufacture of COVID-19 policy and the cult of personality surrounding Dr. Anthony Fauci. We see it in social media platforms censoring and deplatforming those skeptical of corporate power and product. We also see it in the elevation of critical race theory.” The priesthood tells you that you can’t understand the things it purports to know. You’re supposed to proclaim your ignorance and practice cerebral hygiene. Keep your thoughts clean of apparent contradiction (to miss the real ones). Practice ritual gullibility.

Elites use this attitude to sanction technocratic control over the masses. It’s a fundamentally anti-democratic doctrine, profoundly destructive to liberty, especially cognitive liberty. People stop thinking for themselves. Not thinking for oneself invites tyranny. The corporate state’s response to COVID-19, to take a pressing case, is not a rational response to SARS-CoV-2, but rather a strategy for building in totalitarian control of society. Control depends on a mass subjectivity for legitimation, for transforming corporate power into authority, and that subjectivity is the attitude of scientism. It’s a faith-based doctrine. A new religion. Moreover, it’s fascistic.

Circumstances have handed me an illustration. Every year, typical of universities across the nation, the institution where I teach adopts a common theme and organizes classes, curricula, and events around it. This year, the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, or CAHSS (cleverly pronounced “cause”), is rolling out its annual “Common CAHSS” with the theme “Truth: Information, Misinformation, and Democracy.” As you will see, Common CAHSS 2021-22 reeks of progressive angst over the rise of the popular voice and the concomitant decline in the faith in the academic priesthood.

Here is the theme description:

The public’s ability to distinguish truth from falsehood seems to have deteriorated significantly in recent years. There is a widespread deficit in the ability to recognize subject expertise, critically evaluate sources, and synthesize ideas. The very notion that facts exist has been called into question through phrases like “alternative facts.” This deficit has proven catastrophic during the Covid-19 health crisis, where conspiracy theories and YouTube health “experts” have carried more weight for some than the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Meanwhile, unproven and debunked claims about widespread election fraud threaten to undermine our democracy. While these problems can be explained in part by technologies that allow for the rapid spread of information regardless of quality, intentional efforts to misinform the public have resulted in frequent questioning of the existence of scientific truths like climate change, racial and sexual discrimination, and the health benefits of masks and vaccinations. Common CAHSS 21-22 will explore the role of the modern university in supporting the “continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone truth can be found,” which has been part of the University of Wisconsin identity for over a century. In an era where information—both true and false–can be readily accessed from our phones, the function of higher educational institutions must include not only generating and sharing high-quality information but also teaching the critical information literacy skills required to navigate a complex terrain. Such skills are essential to democracy and to making progress on the key issues of our time, including human rights, racial justice, and sustainability.

It concerns me that the persons organizing the theme this year, while almost assuredly the same persons who make a fetish of demographic diversity (what often becomes, to lean on Musa al-Gharbi concept of “curated diversity,” an exercise of white progressives fixing the standpoints of the other groups for whom they claim to make room and give voice), do not appear to be committed to the viewpoint diversity that is an essential element in any valid system of knowledge production. Posing the problem of knowledge in terms of how to immunize consensus or official claims against challenges presumed to be illegitimate gives away the game. In the mind of the authors of the theme description, the problem is not the crisis of science brought on by technocratic government and the corporate imperative of shareholder profits, but by the dissent of conservatives, socialists, and others from corporate state control that threatens the legitimacy corporate governance and thus imperils the status upon which academics depend for reputational promotion and occupational climbing. Insecurity lies at the heart of condescension.

Christopher Freeman, philosophy professor at William and Mary College, opines in his Inside Higher Education article “In Defense of Viewpoint Diversity,” “we have good reason to think that the teaching and research missions of higher educational institutions are better served when those institutions welcome dissenting opinions.” That good reason should be obvious, but it’s not, and it’s that blindness that speaks to the crisis of higher education. “Truth is a process, not just an end-state,” writes social psychologist Jonathan Haidt. In his book, The Righteous Mind, Haidt identifies “obstacles to that process, such as confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, tribalism, and the worship of sacred values.” These are manifest in demands (identified in “The Coddling of the American Mind Haidt published in The Atlantic) for “safe spaces,” “trigger warnings,” and administrative mechanisms for disciplining “microaggressions.” The fact that microaggressions (an Orwellian euphemism for the faux pas) are so real to the academic that administrators will assign mandatory training on the matter shows just how deeply tribalism has corrupted the endeavor. Such training is required at my institution and almost certainly the authors of the text in question are in full support of such mandatory training. Just as they are for mask and vaccine mandates.

While I am reluctant to deconstruct the work of colleagues whom I regard as friends, the theme description shared above is a paradigm of the problem we are facing in higher education. The Common CAHSS 2021-22 theme description is a clinic not only in these obstacles, but in the way academics expertly couch the obstacles in a rhetoric that presumes to bear the truth. In the case of Common CAHSS 2021-22, that rhetoric is drawn from corporate media propaganda. In this blog, in what will appear as something like Karl Marx’s 1875 critique of the program of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Germany (Critique of the Gotha Program), I focus on the text and its relationship to ideology and power. Methodologically, I deconstruct the description’s rhetoric in light of critical media and propaganda studies, as well as the logic of institutional analysis, relevant fields of study of which—given the parroting of corporate media characterizations throughout description, and the absence of any mention of the problem of corporate governance, power, and profit—its authors appear unaware.

Media studies has its roots in the work of American pragmatists, such as George Herbert Mead, the founder of symbolic interactionism (a term coined by his student Herbert Blumer), who argued that democratic society requires forms of communication that allow individuals not merely to be exposed to, but to appreciate the opinions of others, especially from those unlike themselves, as well as develop empathy towards others with whom they disagree. In agreement with his friend and fellow pragmatist John Dewey, Mead saw open and deliberative communicative forms as essential to arriving at genuine consensus and authentic community. Media and propaganda studies formally appears at the New School in New York in the early twentieth century and becomes a central focus of the Frankfurt School, where critical theory is applied to mass communications and propaganda. A contemporary instantiation of work in this area is the work Mickey Huff and his colleagues carry out over at Project Censored.

If one is interested in accessible examples of how to pursue critical institutional analysis, I recommend two documentaries, both by Zeitgeist Films: Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick’s Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media and Mark Achbar, Jennifer Abbott, and Joel Bakan’s The Corporation, the latter based on Bakan’s book by the same name. I show these documentaries in two courses I teach: Freedom and Social Control and Power and Change in America. In Freedom and Social Control, the semester project involves students producing an institutional analysis of a student-selected for-profit corporation or industry. Pharmaceutical corporations and related areas of the medical-industrial complex are always popular topics. Is it the opinion of authors of the theme description that I should criticize students whose findings contradict the edicts of the CDC and FDA?

As will become apparent, the description of Common CAHSS 2021-22 theme is an expression of the same technocratic desire that animates Silicon Valley’s Big Tech oligarchs, a desire captured well by the great propaganda and public relations men of early twentieth century United States, principally Edward Bernays and Walter Lippmann, and the concept of “engineering consent” or “manufacturing consent.” From this standpoint, the goal of apparent intellectual activity is not to interrogate claims but to indoctrinate the public, including deploying strategies to exclude arguments that increasingly resemble what George Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four described as a “thoughtcrime,” aimed at controlling politically unorthodox thoughts that contradict the dominant ideology. Orwell detailed a list of terms associated with the official language of his dystopian world Oceania called “Newspeak,” among them “crimethink,” which refers to politically-wrong thoughts and actions.

In the 1920s, Harold Lasswell, a student of the work of Mead and Dewey’s, as well as Freud, defined propaganda “in the broadest sense is the technique of influencing human action by the manipulation of representations. These representations may take spoken, written, pictorial or musical form.” The Institute for Propaganda Analysis (1937-1942), a think tank founded by a group of historians, journalists, and social scientists, announced its purpose this way: “To teach people how to think rather than what to think.” I am sure many of your have heard that before. That is what should be occurring at the university—not telling people to accept the claims that the 2020 election was the most secure election in the nation’s history, that masks and vaccines are the best way to deal with a pandemic, that blacks are the victims of systemic racism, or that global climate change is caused by human action. The IPA defined propaganda as “expression of opinion or action by individuals or groups deliberately designed to influence opinion or actions of other individuals or groups with reference to predetermined ends.” Almost everything about the theme description speaks to the desire to seek predetermined ends without facts and reason. Only one of the four claims listed in this paragraph highlighted by the theme description enjoys empirical support sufficient to warrant belief, and that is the problem of global climate change.

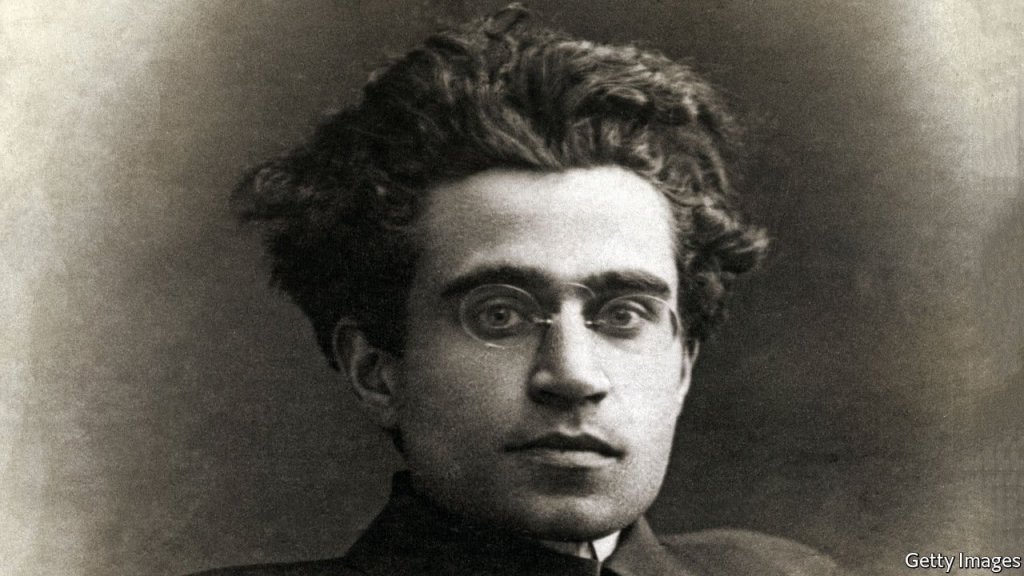

The concept of manufactured consent appears also in the work of Italian Antonio Gramsci in his Prison Notebooks, so named because the notes were written from a prison cell where fascist dictator Benito Mussolini threw Gramsci for crimethink, where it is referred to as ideological hegemony. Gramsci argues that the ruling class governs in two ways: control over the means of violence (the iron fist) and control over the means of ideological production (the velvet glove). Governing a people requires suppressing opposition and leading a majority of the rest. In other words, rule is established through coercion and consensus. Gramsci’s theory is concerned with identifying those institutions that function to bring the masses under hegemonic control, primarily by constructing a consensus reality that conceals or distorts objective reality and dissimulates power. Gramsci understands that economic (or structural) coercion and culture provide an essential context for the work of violence and manipulation. Elites establish a social logic in which its interests are presented as common sense. Thus citizens are conditioned to accept elite interests as their own interests, to accept elite opinion as correct opinion. Those so conditioned not only do not require discipline and punishment, but they often serve as social controllers for the elite on their own volition. Sometimes, they take up the duty with zeal. Oftentimes, in fact.

The consensus Gramsci describes is not finding common understanding in the manner pragmatists propose. Rather it is a manufactured consensus in the sense that enough people are swayed by versions of reality constructed by societal institutions under the control of the ruling class. The significant institutions in modern society are the corporation, the state and its administrative officers and regulatory agencies, the organized media (owned by the corporations), including book and journals, established educational institutions, and major religious organizations. The latter two have often been marked historically as institutions where traditional intellectuals work to some degree outside hegemonic power. This changed over the course of the twentieth century. Gramsci could see that early on.

(For those interested in research deploying Gramscian insights, I use a Gramscian framework in my analysis of anti-environmentalism in my award-winning article “Advancing Accumulation and Managing its Discontents.” published in 2002 in the Sociological Spectrum. This work is relevant to the subject of the present blog. In that paper, I apply Gramsci to the study of corporate-funded climate research largely lying outside the university framework. Crucially, hegemonic production proceeds both inside and outside the university. Maybe some day I will blog about what happened to me when I critiqued anti-environmentalism inside my university.)

I emphasize that my argument is not that there is no objective method for determining the validity and soundness of truth claims. Quite the contrary. Not all arguments that examine the intersection of knowledge and power are postmodernist in character. My argument is that scientific practice, which has a normative basis that I detail below, one that derives from the materialist standpoint, is corrupted by money-power. For this reason, I do not argue for the neutrality of science. Crucially, as philosopher of science professor Sandra Harding noted, objectivity and neutrality are not synonymous. The desire to weed out corrupting influences degrading objectivity in science cannot be a neutral endeavor since it requires identifying forces that bias the scientist.

In his 1942 essay “The Normative Structure of Science,” sociologist Robert Merton, a founder of the sociology of science, developed what has been called “The Merton Thesis,” captured in the acronym CUDOS, composed of four principles of normative science: communism, universalism, disinterestedness, and organized skepticism. I will detail each of these in the next three paragraphs, where it will become obvious to many of you why the problem posted by Common CAHSS is misspecified. Communism here does not refer to the social system envisioned by Karl Marx, but is rather used, according to Merton, “in the nontechnical and extended sense of common ownership of goods,” specifically scientific goods, to represent an ethic wherein discoveries become the common property of the scientific community and society at large. Proprietary control over scientific method and results by corporations corrupts the ethic of communalism in science. Science is the property of humankind.

Universalism means that truth claims are evaluated not on the basis of abstract demographic or ideological categories (class, gender, nationality, race, religion) but on transcultural and transhistorical grounds, that is on the basis of objective and universally accessible methods. Identitarian and postmodernist epistemology corrupts the ethic of universalism. The ethic of disinterestedness follows from the ethics of communism and universalism: the researcher’s work should neither be one of self-interestedness nor one constrained by the narrow group interests that may direct his work. Like corporate power, tribalism corrupts disinterestedness.

Finally, organized skepticism means ideas must be subject to community or popular scrutiny. When the claims elites and intellectuals make are met with doubt and skepticism, when the people lose faith in their institutions, and academics find this unwelcome, and corporations censor and deplatform speech and speakers, indeed when intellectuals and elites smear the skeptical community as “backwards,” “racist,” and so on, we have clear indication that the institution of science has been captured by a subjectivity generated by money-power that dictates practices (for the most part without direct orders) working at odds with the ethos of science.

Merton provides a powerful example of the contradiction between the ethos and practice of science in his observation that a handful of scientists receive a lion’s shared of awards, coveted positions, and grants. This has at least as much to do with the strategic distribution of the means to achieve these than it does with talent. Merton saw the problem early on as a student in the 1930s in his study of the influence of the military on scientific research In his studies of character and social structure with Hans Gerth, and on his own, in such works and White Collar and, especially, The Power Elite, sociologist C. Wright Mills documents the effects of bureaucratic organization on shaping human action and attitude in line with Merton’s concerns (see also see Paul Diesing’s 1992 How Does Social Science Work?). (For those of you who know a bit about sociology, you will already have detected that this work is as much animated by Max Weber’s ghost as it is by Marx’s.)

There was a time when these concerns reached the highest office in the land. In his Farewell Address in 1960, in addition to his trepidations regarding the “military-industrial complex,” President Dwight Eisenhower expresses concern that, because of the control over scientific research by the corporate state, “public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.” He worries aloud that “the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research,” wherein corporate state funding, and the direction that comes with it, “becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity.” Eisenhower feared the “prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars,” of elite control over “project allocations” by the ever-present “power of money.” These problems, he warned, are to be “gravely regarded.” The present conditions fulfill the prediction Eisenhower’s trepidations imply. The neoliberal university is captured by corporate power. Indeed, that the very descriptor “neoliberal” is a common one tells us that the corruption of higher education is well understood. We can say, in Gramscian terms, that the status of intellectual is no longer a traditional but an organic one.

A point of clarification: when I say “deconstruction,” I do not mean in the Derridian sense that language is indeterminable or irreducibly complex. I mean in the critical media and propaganda sense of connecting language to institutional and moneyed power. Again, this is not an exercise in postmodernism, but rather one of historical materialism, where it is recognized that those who control the material means of production (a fact objectively determinable) also control the means of ideological production. As Marx and Engels famously put the matter, in its simplest formulation, “The ruling ideas of any age are the ideas of the ruling class.”

Finally, before turning to the task of deconstructing the target, I want to say that, no, I don’t think the theme was organized with me in mind (although I know my colleagues read my work and, because my arguments fall on the opposite side on almost every item specified in the description, are troubled by me). Rather, I confidently believe the theme was organized with people like me in mind. I am not alone in my criticism of technocracy and corporate propaganda; my criticism is shared by tens of millions of people across the nation (and judging by the private messages I receive, some of my colleagues are reluctant to speak up precisely because of the attitude expressed in the description—they fear ridicule and marginalization). As my writings on Freedom and Reason make clear, I resemble the problem facing the modern university from the standpoint of Common CAHSS 2021-22, namely the problem of popular refusal to accept the progressive doctrine pitched as truth that has corrupted science. Based on missives and rumors, I have apparently become a right-winger on account of this refusal. I hate to disappoint (not really), but I remain a man of the left. Frankly, if people actually understood politics, then I wouldn’t need to say that. But they don’t. So I do.

* * *

Turning directly now to Common CAHSS 2021-22 theme description, the text opens with, “The public’s ability to distinguish truth from falsehood seems to have deteriorated significantly in recent years. There is a widespread deficit in the ability to recognize subject expertise, critically evaluate sources, and synthesize ideas.”

Bracketing “truth” and “falsehood,” the fact that, today, according to scientific polling, more than eight out of every ten Americans believes in human evolution suggest that the public’s ability to distinguish fact from faith has not significantly deteriorated. What has actually happened over the last several years, thanks in major part to the anarchy of the Internet (the unintended consequence of making public a system designed for military purposes), is that alternative sources of information have emerged that function to weaken the hegemony of the corporate owned and controlled legacy media and challenge the legitimacy of the corporate-captured regulatory apparatus and the administrative state. Major social media platforms have been unable to effectively suppress the popular voice and new social media platforms are proliferating in the wake of their attempts. This is a good thing. It challenges power. Which is why from another standpoint it is a bad thing.

Increasing numbers of people are no longer accepting as truth the propaganda of the state corporate apparatus, which includes not only regulatory bodies and the media, but also academia and the culture industry. Contrary to the theme description’s claim, the popular voice hasn’t lost its ability to distinguish truth from falsehood (to be sure, this is a strategic mischaracterization—and a rather obnoxious one). Instead, the people have lost their faith. In some cases, they are immune from the infectious and pathological character of propaganda. The people no longer accept as given that their interpretations of the world are false in the face of prevailing ideological claims of truth. They are thinking for themselves. Again, from another standpoint, this is a dangerous development.

In the 1970s, German sociologist Jürgen Habermas described this problem as a “legitimation crisis,” wherein corporate state actors lose or suffer diminishment of the steering capacity to shape outcomes conducive to realizing their fractional interests. The anxiety academics and cultural managers are experiencing stems from the sense of loss of control over their ability to determine the truth of such matters. The angst is sublimated as an agenda. Social coercion around masks and vaccines represent an attempt to prop up the authority of the medical-industrial complex and its representatives. Organic intellectuals, in the service of corporate governance and profits, shame those who, in the face of considerable evidence have good reason to doubt the efficacy of these measures, dissent from the agenda. The parade of dissenters at school board meetings across the country demanding critical race theory, which has as much valid science in it as intelligent design, be removed from the curriculum is another indication of the crisis of legitimacy.

What is popularly known as “Trump Derangement Syndrome,” or TDS, is a manifestation of this elite anxiety. Progressive elites were horrified by the revolt of the working class Trump’s election signaled. Progressives revile populism in part because it challenges the legitimacy of technocracy and thus their authority. They fear displacement by the popular voice, by the bewildered herd. How dare the deplorables think they can know more that the experts. Progressives regard any attempt to challenge their authority with contempt. I have on occasion had students tell me that, despite their teachers’ assurances that they would be allowed to freely voice their opinions, doing so resulted in ridicule and shaming and, sometimes, ejection from class.

In the minds of most academics, it is not in the realm of possibility that they could be wrong. When they see a fellow academic change his mind, it is not an opportunity to celebrate the way the process of truth is supposed to go, but a reason to think a man has lost his way—maybe his mind. In any case, how can we now trust his judgment? He admits he is wrong! It follows that those who question the opinions of those who are certainly right must be backwards, deluded, stupid, or dangerous. Think of the universities distributed throughout the country as colonies of the elite snobs who dominate the coasts of our nation and you will have a pretty good understanding of what students face when they come to campus. Given how focused the academy is on marginalizing white men, could this be why so many young white men are not bothering to attend college? (For the the record, the Department of Education is not interested in explaining the phenomenon.)

“The very notion that facts exist has been called into question through phrases like ‘alternative facts,’” bemoan the authors, as if there can be only one set of “true facts” or that facts speak for themselves. Facts can be manufactured and presented in a manipulative manner to achieve a desired end—including those facts that face alternatives. I always tell my students, “Facts do not speak for themselves. People purport to speak facts. The default position with respect to such utterances is skepticism.” Demonstrating the importance of skepticism, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a clinic in manipulated fact and interpretation. This is why it is imperative to recognize that the science of propaganda is a technology for manufacturing consent around managed sets of alleged facts to further the interests of cultural, economic, and political elites.

If the complaint here is a lament over the loss of the traditional intellectual who works through some process like that identified by Thomas Kuhn in his The Structure of Scientific Revolution, where disciplinary matrices come together scientifically and establish themselves as knowledge (valid and verified information) to be overthrown by new discoveries and theoretically-organized (re)interpretations of extant knowledge, then the author(s) of description might ask why so many academic have become organic intellectual for corporate state power big and small professing to speak the truth while actually serving as functionaries for money-power and narrow political interests. How can it be that one theory among many about race relations, and, frankly, the least valid and sound among the myriad, can become the foundation for required training in diversity, equity, and inclusivity? This betrays a religious sensibility.

“This deficit [sic] has proven catastrophic during the Covid-19 health crisis, where conspiracy theories and YouTube health ‘experts’ have carried more weight for some than the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.” This bit is so cribbed from legacy media propaganda as to be embarrassing. I will come to “conspiracy theories” in a moment, but “YouTube health ‘experts’”? Like an inventor of the mRNA platform Dr. Robert Malone who warns about leaky vaccines and antibody-dependent enhancement driving mutations and disease? Or perhaps Yale’s Dr. Harvey Risch who demonstrated long ago the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in saving lives? I understand such experts to be all the experts who are not Dr. Anthony Fauci of NIAID or WHO director Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and those others whom they anoint with the authority to speak on the matter (although Tedros’s days as an authority are limited if he continues to express skepticism over mRNA boosters).

The use of the construct “conspiracy theory” to characterize other interpretations of the facts, interpretations organized from positions critical of governmental and corporate power (what you might think would be encouraged at our institutions of higher education), is a classic propaganda tactic to manipulate people into dismissing undesirable interpretations out of hand. One cannot defend a conspiracy theory without become a conspiracist. The term “conspiracy theory” functions as a thought-stopping device preventing the recipient of propaganda from considering that there are conspiracies (which is why the legal category exists) and that one can have theories about them. Of course, what they mean by the term is any theory that disrupts the authorized or official narrative; but the charge is effective is marginalizing other viewpoints. (See Science and Conspiracy: COVID-19 and the New Religion.)

The author(s) appear to suffer some ignorance about the history of the CDC, an organization, along with the FDA and the USDA, long ago captured by corporate power. It explains the naïveté with respect to power. Is regulatory capture a conspiracy theory? Given history, how could anybody think such a thing? It’s not a difficult thing to know. The web site Investopedia has a solid definition of the phenomenon: “Regulatory capture is an economic theory that regulatory agencies may come to be dominated by the interests they regulate and not by the public interest. The result is that the agency instead acts in ways that benefit the interests it is supposed to be regulating.” (For those interested in the evidence and history of regulatory capture, there are several talk available on the Internet of Richard Grossman, director of Program on Corporations, Law, and Democracy, covering the matter in-depth: “Defining the Corporation, Defining Ourselves” and “Challenging Corporate Law and Lore.”)

“Meanwhile, unproven and debunked claims about widespread election fraud threaten to undermine our democracy.” Another bit of redirection cribbed from legacy media propaganda. The phrase “unproven and debunked claims” assumes what requires investigation to know, such as a forensic audit of the elections, if not in all the states, at least in key states: Arizona (where one is underway), Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. The claim that claims about widespread election fraud are “debunked” amounts to disinformation (which would have been nice to have included in the theme’s title). If truth matters, then the claim that some claim has been debunked when it hasn’t is revealing—especially when it is repeated ad nauseam. There is overwhelming evidence of election irregularities that point to a rigged election (see Peter Navarro’s three-part report). If what went down in November 2020 had gone down in a Third World country with a regime the US wished to see stay in power, you’d hear all about it.

The claim that accusations of widespread election fraud undermine democracy is an opinion that feels wrong in light of the importance of ensuring election integrity in building public confidence in the electoral process. This is why we audit elections, something that, before Joseph Biden’s election (or installation) in the White House, progressives were adamant about. Of course, progressives are right to challenge election results that smell funny. That’s what democracy looks like. Except when conservatives do it. Then they’re undermining our democracy.

Here’s a fact we might acknowledge if the people matter: a large proportion of the population believes something went wrong with our elections in 2020 and they want to know why. One third of all voters and fifty-six percent of Republican voters in a June survey expressed their belief that Biden won the White House because of voter fraud. One might argue that this shows that Republicans live in a bubble operating on “alternative facts.” But most of the more than eight of ten Democrats who believe Biden won the election legitimately do not bother to base their opinion on evidence. I have yet to have a conversation with a progressive who will even look at the evidence. That’s anecdotal, of course, but don’t forget that more than four of every ten Democrats believe that half of all those who contract SARS-CoV-2 wind up in the hospital.

Leaving doubters in doubt surely undermines democracy more than investigating claims of election fraud—which not investigating exacerbates. If this were the other way around, does anybody really believe that those who wrote this description would not be demanding an investigation into the election in the spirit of “continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found”? I am confident that the authors believe the Russian collusion and Ukrainian phone call controversies where valid bases on which to overturn a democratic election. The Steele dossier was treated as the Gospel truth in my suite.

The propaganda here means to impress people with the “truth” of a disputed claim, that the 2020 election was the most secure election in our nation’s history. On the face of it, the claim is unbecoming of a university that states the pursuit of truth as its raison d’être. That the theme description treats the matter as a foregone conclusion betrays its pretense to objective inquiry.

“While these problems can be explained in part by technologies that allow for the rapid spread of information regardless of quality, intentional efforts to misinform the public have resulted in frequent questioning of the existence of scientific truths like climate change, racial and sexual discrimination, and the health benefits of masks and vaccinations.” This is a lament over the rapid spread of information with which the authors disagree. What is more, in keeping with the rest of the description of the theme, this sentence assumes as scientific truth that which has not been demonstrated as such.

Is climate change “scientific truth”? To be sure, climate change is a consensus position among those with expertise in this area. It happens to be a consensus of which I am a part (having published papers and given talks on the matter, I am convinced climate change is a problem), but is it “truth”? If by truth one means a fact or belief that is accepted as true, then, yes, it is true for a majority of those trained in this area. Should we listen to those who challenge that consensus? I do. I have learned a lot from those who call into question the certainty—and self-righteousness—with which those who make arguments concerning the causes and effects of climate change express their position. Assuming the fact of climate change, the matters or theory and policy are still very much contested terrain.

What about racial discrimination? Is this a scientific truth? Take the claim of systemic racism in the US criminal justice system. There is arguably no better example of debunking that the large scientific literature demolishing the claims of systemic racism. Every major scientific study produced over the last several decades has failed to find evidence of systemic racism in, for example, lethal civilian-police encounters. Recall that the description bemoans the disregard of subject expertise. Well, I am an expert on the subject of the criminal justice system and I can testify to the fact that my expertise has been entirely disregarded in the formulation of every position and action taken on the question of systemic racism at my university, action that has put the debunked claims regard systemic racism in lethal civilian-police encounters at the center of consternation. Why? Clearly not because of any concern for the truth. If people understand that the claim that lies at the core of the Black Lives Matter movement is utterly false, then the progressive agenda will receive a shattering blow. I have the wrong opinion, however expert and informed it is.

I have already touched on this matter of claims about the health benefits of masks and vaccinations. These have always been subject to dispute. And for good reason. There is little science behind the efficacy of masks. The discipline of industrial hygiene tells us that attempting to stop a virus with a mask is analogous to trying to keep mosquitos out of one’s yard by installing a chainlink fence. State corporate propaganda regarding vaccination has imploded in light of the real world facts concerning its efficacy and safety. Public policy around COVID-19 has been a total shit show. I need not say any more about this.

“Common CAHSS 21-22 will explore the role of the modern university in supporting the ‘continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found,’ which has been part of the University of Wisconsin identity for over a century.” This is the “Wisconsin Idea,” which I fought to keep in the System’s mission statements. I hedge on possibility of finally knowing the truth, but I do not hesitate to pursue it. Given the things assumed as true in the description about which there is no established truth, how could Common CAHSS 21-22 be an exploration of the role of the modern university in this task? Again, what lies behind the description is not really an expression of scientific desire, but an expression of scientism, an ideology gathering about itself scientific pretense. A scientist searches for the truth. He does not assert it. A science welcomes challenges. He does not reject them out of hand. Science is not religion.

“In an era where information—both true and false—can be readily accessed from our phones, the function of higher educational institutions must include not only generating and sharing high-quality information but also teaching the critical information literacy skills required to navigate a complex terrain.” In context, “critical information literacy” sounds like an Orwellian euphemism befitting the Ministry of Truth my colleagues want the university to be. For those of you who are unfamiliar with the term, its origins are found in the society of radical librarians. The Association of College and Research Libraries defines information literacy as “the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.” The critical side of information literacy demands that practice make explicit the role of power in shaping the production of knowledge.

However much critical information literacy may sound like the approach I am using to critique the theme description, critical information literacy is really a cover for the type of woke approach Haidt, Merton, and others correctly see as corrupting reason and science. One detects this in the work American University recommends for the practice: “In Pursuit of Antiracist Social Justice: Denaturalizing Whiteness in the Academic Library” (Library Trends, 2015), “Neutrality is Polite Oppression” (keynote presentation at Critical Librarianship and Pedagogy Symposium, University of Arizona 2018), and “That Which Cannot be Named: The Absence of Race in the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (The Journal of Radical Librarianship, 2019). These titles are dripping with what Brown University economics professor Glenn Loury calls “identitarian epistemology.”

The description concludes with: “Such skills are essential to democracy and to making progress on the key issues of our time, including human rights, racial justice, and sustainability.” Yes, albeit not as defined by and administered as policy by progressives. If we really wanted to make progress on these issues (racial justice is in the bank, but the others are in play), then we would open up the discourse to everybody, not just confine it to those who claim expertise in repeating propaganda lines. However, the framing of Common CAHSS 2021-22 suggests another cause, to (a) marginalize those students and faculty who do not accept as truth the assumptions of the description (each of which could be couched in neutral language), assumed (probably correctly) to be the consensus of most faculty and administrators on campus, and (b) strategize better methods of presenting as true state corporate propaganda. In sum, the task at hand is to assert a priori knowledge of the truth and then figure out ways to stop people from challenging it.

* * *

I want to conclude by returning to the matter of expertise. I am a criminologist. I am the only criminologist at the campus where I teach. I have a special responsibility to present the range of criminological perspectives. Are all criminologists in lockstep theoretically? Are there no disputes in that discipline? Hell no. Criminology is one of the most theoretically-diverse fields in the social sciences. Suppose the criminologists we believed were the ones the corporate state told us to believe and, furthermore, that you could not know any different because you were not one. That’s what’s happening. That and this: the university does not proceed in an interdisciplinary fashion (it used to, see here: Notes on Problem-Focused Interdisciplinary Education.) Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy write about this in their 1967 Monopoly Capital (you can read the introduction here). Mills writes about this in his 1959 Sociological Imagination. Noam Chomsky makes similar arguments. What these authors share is a broad understanding of scientific production beyond their expertise. Chomsky is a linguist. He denies there is a relationship between linguistics and his analysis of power. I think there is, but should we ignore Chomsky’s analysis of power because that’s not his area of expertise?

When my labor union passed a resolution condemning systemic racism in lethal civilian-police encounters, not a single member contacted me to find out if the premise were true. It was as if my institution had no criminologist in its employ. The result was a public position taken based on a demonstrably false premise. Would it have mattered if I had intervened? No. It would only have confirmed something had happened to me. If one disagrees with Black Lives Matter it’s not because BLM and its supporters are wrong; it’s because the dissenter’s politics are right in a partisan sense. The resolution was never concerned with accuracy or facts. Its purpose was virtue signaling to a particular audience. Experiences like this testify to the power of ideology. If objections to my arguments were for some other reason than ideological, then productive conversations might ensue. But they’re not.

If I told you that you must believe what I say about criminology or political economy because you do not have a PhD in sociology and I do, then I hope that you would call me on my arrogance. Many don’t—at least not when they don’t need my expertise to legitimize their own arguments. You have probably noticed that, for most people, what they believe is what their side believes, and they appeal to expertise only on that side, telling others to listen to the experts. Their experts. As if they could know by the lights of their own arguments. It’s like this slogan “follow the science.” What they really mean is that you should follow the scientists who agree with them. And they are frustrated when you don’t. You will get called names for it.

Here’s an idea: How about we practice science? The university, like the other institutions of Western society, have been captured by corporate power. The ideas expressed in the theme description are the ruling ideas. As Marx and Engels put it in The German Ideology, and I will reproduce the quote once more, “The ruling ideas of any age are the ideas of the ruling class.” The ruling ideas appear everywhere. If “Black Lives Matter” appears as a corporate decal or a city street’s name, then you know that it is not a revolutionary slogan. In Gramscian terms, with respect to university faculty, part of the white collar strata, the new middle classes, the traditional intellectual has become the organic intellectual. He no longer represents the general interests. He instead represents the corporate class—even if he thinks he represents the marginal and oppressed.

Noam Chomsky famously observed that at the level of first approximation there are two targets of propaganda. There is the eighty percent of the population who must be made to be disinterested in how the world works. Then there is the twenty percent of the population who must be deeply indoctrinated, for it is their role to define reality for the other eighty percent. He calls the twenty percent “cultural managers,” and among them he finds the academic to be especially influential in misdirecting and misleading the public.