It’s obvious to attentive and compassionate Americans that standing down police and prosecutors and implementing various reforms, such as cashless bail, especially where it leads to the release of serious offenders back into society where they can do more harm before their cases have been properly adjudicated, has compromised the criminal justice system’s ability to protect citizens from harm by effectively controlling serious deviant behavior. The United States is now experiencing a significant crime wave, an increase in crime and violence that comes after decades of significant reductions in the harms associated with crime—reductions that resulted largely from the historic expansion of the criminal justice apparatus in the early 1990s—and woke progressive social policy is to blame.

The problem of serious crime and violence that began as a public issue in the late 1960s, a problem that grew worse each decade until the culmination of previous interventions and the full-court press in the early 1990s turned the tide, may feel like the distant past today in the early 2020s, but remembering that period, what was behind it, and what we did about it, is highly relevant to understanding the rise in serious criminal offending over the last few years and for shaping public policy going forward. We have now have a before-and-after comparison with which to make rational policy choices that can strengthen public safety against serious deviant behavior. The findings of a historical social experiment are in and they recommend crime control—within due process constraints set down in the United States Bill of Rights. We need more police. We cannot abolish prisons.

Baltimore

For a detailed account of the forces that cause social disorder and serious crime see my blog The Denationalization Project and the End of Capitalism, published on January 30, 2020. This blog not only sheds light on the growth of crime by describing its cultural, economic, and political context, but also its racial character. I want to encourage you to read that blog; over the next couple of paragraphs, I will summarize that content to more explicitly connect this history to the crime problem.

After the immigration restrictions of the early 20th century, which cut off the flow of cheap foreign labor from Europe, American industrialists recruited native-born workers from the South, millions of whom where black, enticing them to leave the backwards and violent region of their birth for northeastern and midwestern urban centers. Back then, around 85 percent of blacks lived in the South. By 1970, the figure had fallen to nearly 50 percent. Industrialists sought cheap labor through a strategy of internal migration; black Americans were provided opportunities to improve their lives and escape poverty and racial oppression. Black Americans became crucial to industrial production and those jobs undergirded family stability in black-majority neighborhoods.

As I explain in that blog, the cutting off of immigration and the integration of black workers in industrial production led to growing worker solidarity which allowed the proletariat to command higher wages and better working conditions. Organized labor played a substantial role in these developments. Moreover, the growing affluence and expectations of black Americans fueled the movement for racial equality. At the same time, the rise of labor power, as well as the rising organic composition of capital (OCC), led to a fall in the rate of profit. This is explained by the theory of surplus value. Labor power generates both workers wages and the surplus value capitalists convert to profit in the market. This is the process of capitalist accumulation. The more of the value produced labor takes in wages, the less value is left over for the capitalist (who produces none of that value). The result is a fall in the rate of profit (sometimes referred to as the “profitability crisis”). Furthermore, the rising OCC results in workers disemployed by automation, mechanization, rationalization and scientific management. Reducing consumer power, rising structural unemployment contributes to a realization crisis wherein surplus cannot be realized as profit in the market.

Beginning in the 1960s, the capitalist class in the United States, represented for the most part by progressives and the Democratic Party, sought to restore the rate of profit by organizing against the working class, abolishing immigration quotas and facilitating the off-shoring of industrial production—in a word, elites globalized the capitalist mode of production. Globalization, by pitting native workers against foreign labor at home and abroad compromised the process of racial integration that had proved so successful in raising proletarian consciousness. This was not accidental. Real racial justice promised to deprive the ruling class of the mechanism they had long used to keep the working class fractured and resentful. By the 1990s, with neoliberalism having restored the rate of profit to some degree (at the very least having stemmed the hemorrhaging), elites were openly repackaging racial animosity in order to fracture the working class—this time as antiracism.

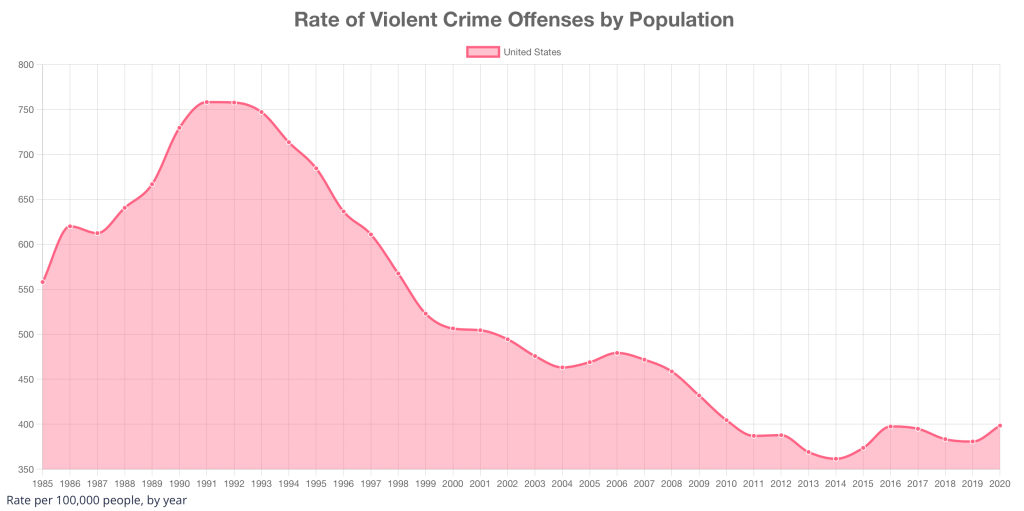

Globalization had devastating effects on the working class, especially black Americans, who became trapped in America’s deindustrialized urban only to be managed by the custodial state progressive stood up during the Great Society (see Poor Mothers, Cash Support, and the Custodial State). In response to the explosion of crime and violence the war on labor and progressives had predictably brought to America’s working class neighborhoods, the establishment waged another war: the war on crime and drugs. The results were a vast expansion of the criminal justice apparatus, which disproportionately affected black men, and a historic reduction in crime and violence—the latter once the state got right the mix of deterrence (the realm of policing) and incapacitation (the realm of the corrections). In the final analysis, then, mass incarceration is a consequence of globalization. Since the corporate state had no intention of repairing the economic devastation globalization brought to working class communities, especially black-majority neighborhoods, crime control was the only real option available. It worked as you can see in the chart below.

Source: FBI

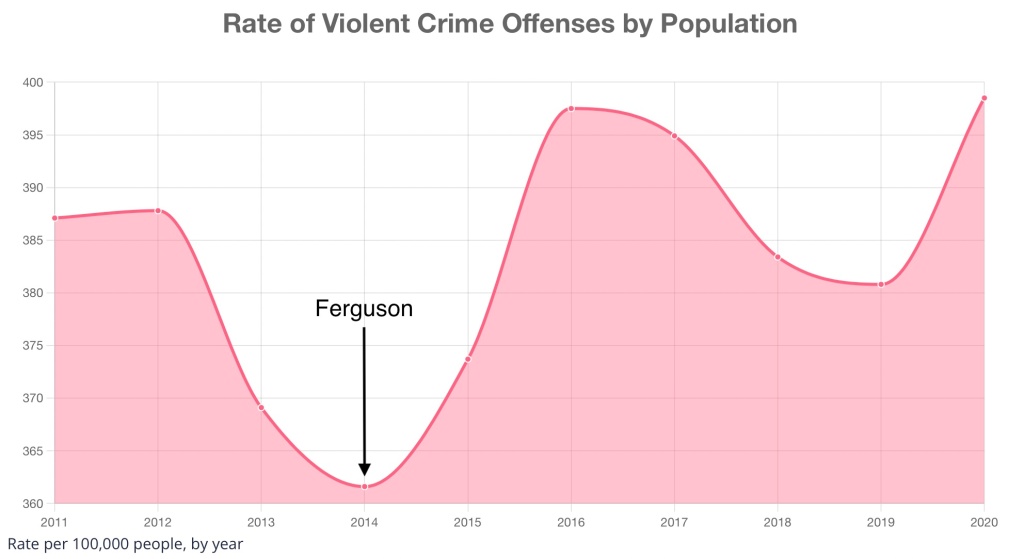

However, since 2014, the historic downward trend in crime and violence have been reversed, and (except for most of the Trump presidency) has steadily increased, accelerating since the spring of 2020. According to National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) data, between 2020 and 2021, violent crime incidents and offenses increased 29 and 27.5 percent respectively. Homicide for both increased by more than 40 percent. Robbery by 18 percent. Rape incidents and offenses by 38 and 37 percent respectively. Property-crime incidents and offenses 22 percent and 21 percent respectively.

Taking a longer view, we can date the upward trend in serious crime to the year of Ferguson, the moment that decades of work manufacturing mass belief in “systemic racism” found its poster child in Michael Brown, the origin of the “hands up” myth. (See Demoralization and the Ferguson Effect: What the Left and Right Get Right (and Wrong) About Crime and Violence.)

Source: FBI

In the run up to the most recent midterm elections, Hillary Clinton, the failed candidate for president in 2016, who, you will recall, referred to black youth in the 1990s as “super predators,” claimed recently that red states are as bad for homicide as blue states. Criminologists reading this blog will recognize that this is the wrong unit of analysis. Crime is worst in cities run by progressive Democrats. In fact, of the 30 American cities with the highest murder rates, 27 have Democratic mayors—and at least 14 Soros-backed prosecutors, with many more prosecutors politically progressive and sympathetic to the woke line.

The increase in crime is not only because Democrats have weakened the criminal justice response; through the teaching of racial animosity, Democrats have given young black men and women permission to commit crime as reparations-in-kind (see Is There Systemic Anti-White Racism?). Over the last decade, the corporate state media, legitimizing its propaganda by appealing to the expertise of the progressional and managerial strata, functionaries (or effectively so) ensconced in academic institutions, and grievance merchants standing up activist organizations, have pursued a campaign to convince Americans that the nation is shot through with racism and that whites are to blame.

Zack Goldberg “How the Media Led the Great Racial Awakening,” Tablet (8/4/2020)

With the crackpot academic construction critical race theory in back of their public messaging, woke progressives aggressively disseminate the falsehoods promulgated by the corrupt Black Lives Matter campaign, myths that paint for the imagination cops prowling about America’s inner cities looking for young black men to murder. As I will show in this blog, the claims of BLM are false. (For more on BLM, see What’s Really Going On with #BlackLivesMatter; Corporations Own the Left. Black Lives Matter Proves it.)

In her 2016 book The War on Cops: How the Attack on Law and Order Makes Everyone Less Safe, Heather Mac Donald examines the “Ferguson effect,” a phenomenon identified in 2014 by St. Louis police chief Doyle Sam Dotson III following the police shooting of Michael Brown. In a St. Louis Dispatch story (“Crime Up After Ferguson”), Dotson notes that police officers, cowed by popular antipolice rhetoric, had become reluctant to fully engage their duties, emboldening lawbreakers already encouraged by popular delegitimization of law and order. (Mac Donald had first broached the subject in a May 2015 Wall Street Journal op-ed, “The New Nationwide Crime Wave.” She expanded her argument in The War on Cops.) The balance of this blog will be devoted to debunking the claims manufactured and disseminated by the woke progressive establishment, as well as to a too often ignored consequence of globalization: the destruction of the black family.

* * *

Portland, Oregon

I begin with the false claims of woke progressivism, which actually represent a body of propaganda designed to shift the blame away from the policies of the Democratic Party and onto the party’s political enemy, the populist-nationalist, that is, those who represent the organic interests of the working class, whom progressive elites depict as backwards and racist.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Police-Public Contact Survey, around 60 million residents 16 years of age and older report having at least one contact with police annually. It might surprise you to learn the number is that large. In fact, it’s much larger than that, given that many individuals reporting contact have more than one encounter with the police in a year. What this means is that, with the US population at more than 330 million citizens and residents (with tens of millions more here illegally), the police have their hands full. Among the advanced Western democracies, the United States is exceptional for its rates of crime and violence.

It might also surprise you (given media coverage) that most contacts involve white civilians, with females slightly more likely to experience contact with a police officer than males. However, this is because whites, especially white females, are more likely to initiate the contact, e.g., in reporting a crime or a disturbance. Males (at around 3 percent) are more likely than females (around 1 percent) to experience threats of use of force. A higher percentage of blacks (around 3 percent) and Hispanics (also around 3 percent) are likely to report experiencing threats or use of force than whites (at around 2 percent). Around 4 percent of blacks and the same percent of Hispanics report having been cuffed during contact, compared to around 2 percent of whites and other races.

That cuffing is reported as the most common use of force when force is reported is a significant fact. Cuffing has become routine at agencies because of the risk to officers when detainees and arrestees have their hands free. This change in policy has contributed to a significant reduction in death and injury occurring to police officers. One may think of this as a workplace safety issue. The negative public perception around routine cuffing is driven by the fact that blacks and Hispanics are more likely to come into contact with police given the overrepresentation in serious crime. But their race makes them no less likely to be a danger if allowed to remain hands free.

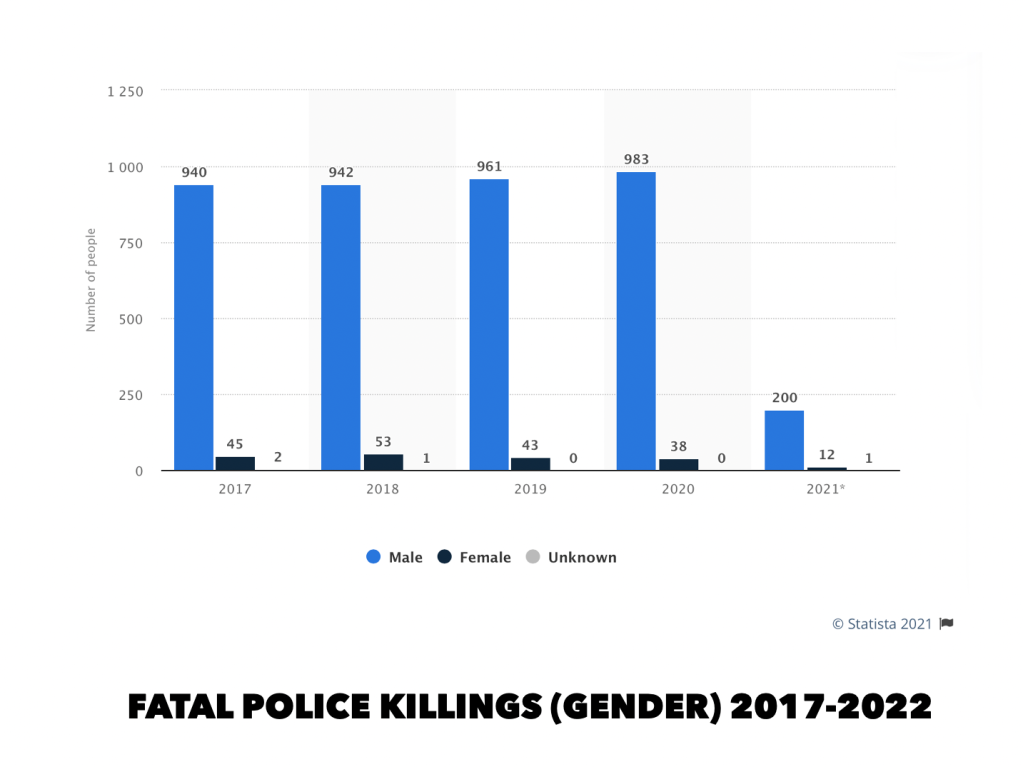

The most serious outcome of civilian-police encounters is lethal violence, resulting in either the death of the civilian or the death of an officer. Fortunately, the latter is a rare occurrence these days; however police officers in the United States kill approximately a thousand civilians annually. According to Mapping Police Violence (based on police data, the Washington Post, and the website Fatal Encounters), around 97 percent of these deaths result from shootings. Most of those shot by the police are armed and the majority of those killed are male—96 percent in 2020, according to the Washington Post (see my blog The Police are Sexist, too).

Whites make up the largest proportion of those shot by the police, approximately half of the total number, with blacks and Hispanics in roughly equal proportions representing the other half of fatalities. Since many sources (the Washington Post/Fatal Encounters) mix ethnicity and race, and since most Hispanics are racially white, the proportion of whites killed, if ethnicity is abstracted out, becomes larger. In other words, in terms of frequencies, whites are far more likely to be shot and killed by the police than are blacks or nonwhite Hispanics, a fact that might surprise the reader given the message pumped out by the culture and media industries. The reader might ask himself: why would the media systematically hide this fact from the public? The answer is that it follows from the logic of the racial animosity project.

Note the large number of unknowns for years 2021 and 2022. Data are still being analyzed for these years (and 2022 is not yet over). There is no reason to believe the pattern will deviate from the one the previous years established.

To be sure, black males, constituting around six percent of the US population, are, at around between a quarter and a third of the total number, overrepresented among those who are killed by the police. But, as I will explain in this blog, this is not because of racist white cops, but rather a consequence of black overrepresentation in serious crime and situational factors, such the threat posed to police officers by the actions of those with whom they come in contact.

The systemic misrepresentation of the facts has had a massive impact on public perceptions. For example, contrary to the widespread belief, with one survey finding a large percentage of blacks and white progressives believing the police kill a thousand or more unarmed blacks annually, fatal police shootings of unarmed blacks number around 22 per year. Isn’t any number of unarmed fatalities too many? Perhaps. However it’s worth keeping in mind that the category “unarmed” is misleading given that hands and feet are prehistorically the first weapons men utilized in violent encounters with other men. Hundreds of deaths occur every year in the United States from hands and feet, or “personal weapons.” In fact, in 2020, FBI crime statistics found that 662 homicides were committed with personal weapons. That’s more people than were killed by rifles that year. And the most important point to emphasize here is that the police do not kill a thousand of more unarmed blacks every year.

Zack Goldberg “How the Media Led the Great Racial Awakening,” Tablet (8/4/2020)

The prevailing progressive narrative about the police is behind the surrounding moral panic. In a recent article by Justin T. Pickett, Amanda Graham, and Francis T. Cullen, “The American Racial Divide in Fear of the Police,” published in Criminology in January of this year, a review of surveys finds that about four in 10 blacks report being “very afraid” of being killed by the police, a statistic that is roughly twice the share of black respondents who reported being “very afraid” of being murdered by criminals, a statistically much greater risk, as well as about four times the share of whites who reported being “very afraid” of being killed by the police. In a survey conducted by Eric Kaufmann of the Manhattan Institute in April of last year, eight in 10 blacks believed that young black men were more likely to be shot to death by police than to die in a car accident. It feels condescending to even have to report that the risk of dying in a car accident is much greater than being shot by the police (but I guess I have to).

I recently experienced firsthand the fear progressive misinformation generates. At a recent conference held in Nashville on issues concerning the black community, where I presented an analysis on these numbers (similar to the one presented in this blog), a panelist, Debbie Griffith, affiliated with the University of Central Florida, shared her doctoral work, “Lessons My Parents Taught Me: The Cultural Significance of ‘The Talk’ within the Black Family,” concerning that moment wherein black parents and community members sit down young black boys and teach them how to behave when interacting with cops as a life-saving exercise, instructions that come with the claim that cops are racist and see black males as a criminal threat (she used videos from Trevor Noah’s The Daily Show on Comedy Central to illustrate). An audience member pointed out that white families also have a version of the talk, since it is widely understood that cops have a dangerous job and assume males of any race or ethnicity are a potential threat (see Jerome Skolnick’s pioneering work on the “symbolic assailant” in Justice Without Trial). But there is a difference, the audience member noted: the talk in white families is not racialized.

The expected rebuttal is that it doesn’t have to be racialized for whites because cops aren’t racist against whites. However, given that there is no evidence that cops are racist or that black males are any more likely to be shot by cops than white males after taking into account benchmarks, such as proportional involvement in serious crime, as well as situational factors, for example pointing a gun at an officer or rushing officers with a knife, the function of the talk in black families is to socialize young black males with a false perception of police officers, a perception that likely leads some black males to behave more aggressively towards police officers. (This is a trend that police officers have not only taken in stride, but has led to their being less likely to escalate force on their end compared to similar encounters with white civilians, who, again, despite being much less likely to be involved in serious crime, account for most deaths at the hands of police officers.)

Again, I want to be clear, there are racial disparities when fatal police shootings are viewed in relation to population. The most common explanations for these, as well as other disparities in the criminal justice system, are implicit race bias and systemic racism. I’m sure readers have heard as truth the facts that racial bias is woven into the system and its institutions, in addition to existing in the minds of officers, prosecutors, judges, and juries, and that systemic racism, the complex of institutional arrangements, structures, and systems that disadvantages blacks and other minorities, is a serious problem in American society and across the West. However, these claims are unsupported by the evidence.

The problem of racial bias in civilian police encounters has been extensively studied. I want to mention two that highlight the problem with disproportionality and perceptions of bias before moving on to the hot-button issue of fatal police encounters. See The Problematic Premise of Black Lives Matter.)

Charles Epp, Steven Maynard-Moody, and Donald Haider-Markel’s 2014 Pulled Over: How Police Stops Define Race and Citizenship, finds that, of drivers stopped by police, many of these stops constituting investigatory stops with neither reasonable suspicion nor probable cause to justify them (what we used to call “aggressive patrolling”), the proportion of racial minorities is almost double that of whites. Using traffic stops to get around Fourth Amendment law is a serious problem, and there definitely needs to be reform in this regard, but racial disparities in such stops—or in anything else in life—is not evidence of racism.

To illustrate, as I point out in The Police are Sexist, too that males are overrepresented in police shootings compared to females. In 2020, men were more than 25 times more likely to be shot and killed than women. “Are we to conclude from this that police are therefore sexist? Of course not. No one would assume that police are biased towards men and therefore more likely to shoot and kill them. No one assumes this because it’s immediately obvious that males are overrepresented in serious crime, whereas females are underrepresented.” I go on to elaborate the point: “male overrepresentation in serious crime causes men to interact with police more frequently than women and, as result, the risk of a lethal encounter with police officers is greater for men than women.”

Jack Glaser, in Suspect Race: Causes and Consequences of Racial Profiling, also published in 2014, contends that, while implicit stereotyping is not racism but an aspect of normal cognition (this was suggested decades before by Skolnick), it is nonetheless harmful and undesirable. In response to these and other findings, implicit bias training programs have been stood up across the nation to develop officer awareness of how attitudes and actions contribute to demographic disparities in the administration of the law. The body of research assessing these programs is not encouraging.

One of the difficulties with arguments from implicit race bias and systemic racism is that claims made on these grounds often take as evidence unexplained variation in racial differences, treating these as indicators of racism. Perhaps this is partially understandable given the difficulty in accessing the interior mental states of officers and criminal justice practitioners and the abstractness of notions of systems. However, it means that conclusions are the work of interpretations that rest, especially on notions of implicit racism, on unfalsifiable assumptions and circularity, where the fact of disparity become evidence of the cause of disparity. On the other hand, if disparities can be accounted for by other factors, the claims of systemic racism become increasingly untenable.

Heather Mac Donald usefully summarizes the literature on this problem in an article “Are We All Unconscious Racists?” published in the City Journal in fall 2017. She cites Joshua Correll, a psychologist at the University of Colorado studying police decisions to discharge their weapon, who finds that officers are slightly quicker to identify an armed black target as armed than an armed white target and slower to identify an unarmed black target as unarmed than an unarmed white target. However, Correll does not find that officers are more likely to shoot an unarmed black target than an unarmed white one. Mac Donald summarizes, “faster cognitive processing speeds for stereotype-congruent targets (i.e., armed blacks and unarmed whites) do not result in officers shooting unarmed black targets at a higher rate than unarmed white ones.”

Mac Donald wonders whether different reaction times might be attributable to the fact that “black males have made up 42 percent of all cop-killers over the last decade, though they are only 6 percent of the population” or the fact that “individuals involved in the daily drive-by shootings in American cities are overwhelmingly black.” For Mac Donald these are rhetorical questions. Indeed, as I will note below, according to FBI data, black males are responsible for roughly half of all homicides in the United States. Blacks are even more overrepresented in robbery. In light of the statistics, I argue in my essay “Mapping the Junctures of Social Class and Racial Caste” that it is not police racism that causes black overrepresentation in crime, but rather black overrepresentation in police statistics is a consequence of black overrepresentation in the types of crime on which the police focus.

Even more damning to the implicit race bias claim than Correll’s failure to show that indications of bias explain police decisions to shoot civilians is Washington State professor Lois James’s finding that officers waited longer before shooting an armed black target than an armed white target and, moreover, were three times less likely to shoot an unarmed black target than an unarmed white target. James hypothesizes that, because of the contemporary racial climate surrounding policing, officers second-guess themselves when confronting black suspects. This finding provides evidence for Dotson’s Ferguson effect. As readers will see in a moment, economic Ronald Fryer theorizes that the consequences of shooting suspects obviates any racial bias they may harbor.

Awareness of the problem of racial disparities in the criminal justice system is long standing. William Wilbanks, in The Myth of a Racist Criminal Justice System, published in 1986, produced a comprehensive survey of contemporary research studies, searching for evidence of discrimination by police, prosecutors, judges, and prison and parole officers, finding that, although individual cases of racial prejudice and discrimination do occur in the system, there is insufficient evidence to support a charge of systematic racism against blacks in the criminal justice system. “At every point, from arrest to parole,” Wilbanks concludes, “there is little or no evidence of an overall racial effect.” Robert Sampson and Janet L. Lauritsen’s 1997 comprehensive review of studies of the criminal justice system, a metanalysis published in Crime and Justice, also finds “little evidence that racial disparities result from systematic, overt bias.” In the early 1980s, Joan Petersilia of the RAND corporation came to a similar conclusion.

Doubts about the claims of racial bias and systemic raised were raised anew in 2016 with the high-profile publication of Mac Donald’s book. Her book was followed by Harvard economist Roland Fryer’s 2019 paper, “An Empirical Analysis of Racial Differences in Police Use of Force,” published in the Journal of Political Economy, available much earlier as a preprint (2018) and a working paper (2016). The New York Times covered the working paper in a 2016 article, so the findings were widely available well before the summer months of 2020.

Must read paper: Fryer’s 2019 article, “An Empirical Analysis of Racial Differences in Police Use of Force,” published in the Journal of Political Economy.

While finding unexplained disparities in nonlethal civilian-police encounters involving force (which supports Epp and associates’ thesis), when turning his attention to the most extreme use of force, i.e., officer-involved shootings, Fryer found no racial differences in either the raw data or when contextual factors are considered. Fryer argues that the patterns in the data are consistent with a model in which police officers are utility maximizers. Fryer suggests that lethal force carries costs great enough to deter officers from using the highest level of force at their disposal.

Fryer is hardly alone in his failure to find racist patterns in lethal police shootings In 2018, psychologist Joseph Cesario and colleagues, in Social Psychological and Personality Science, found, adjusting for crime, no systematic evidence of anti-black disparities in fatal shootings, fatal shootings of unarmed citizens, or fatal shootings involving misidentification of harmless objects. The authors concluded that, when analyzing all shootings, exposure to police, given crime rate differences, accounts for the higher per capita rate of fatal police shootings for blacks. The fact pattern indicating exposure: at least half of homicides and more than half of robberies in America are attributable to black males. Moreover, black males account for some one-third of other serious crimes (aggravated assault, burglary).

David Johnson, Cesario, and others, in the pages of the 2019 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, refer to the effect of rates of violent crime as the “exposure hypothesis,” i.e., that serious criminal activity increases the likelihood of officer-civilian encounters, and this influences the frequency of policing shootings. The evidence Johnson and associates used in their study indicate that, taking crime rates into account, the bias in shootings actually appears to be against whites.

In a study published in Journal of Crime and Justice, also in 2019, Brandon Tregle and colleagues, when focusing on violent crime arrests or weapons offense arrests, found that blacks appear less likely to be fatally shot by police officers. Rutgers’ Charles Menifield and colleagues found, in a study published in Public Administration Review in 2019 that, although minority suspects are disproportionately killed by police, white officers appear to be no more likely to use lethal force against minorities than nonwhite officers. Most people killed by police are armed at the time of their fatal encounter, and more than two-thirds possess a gun.

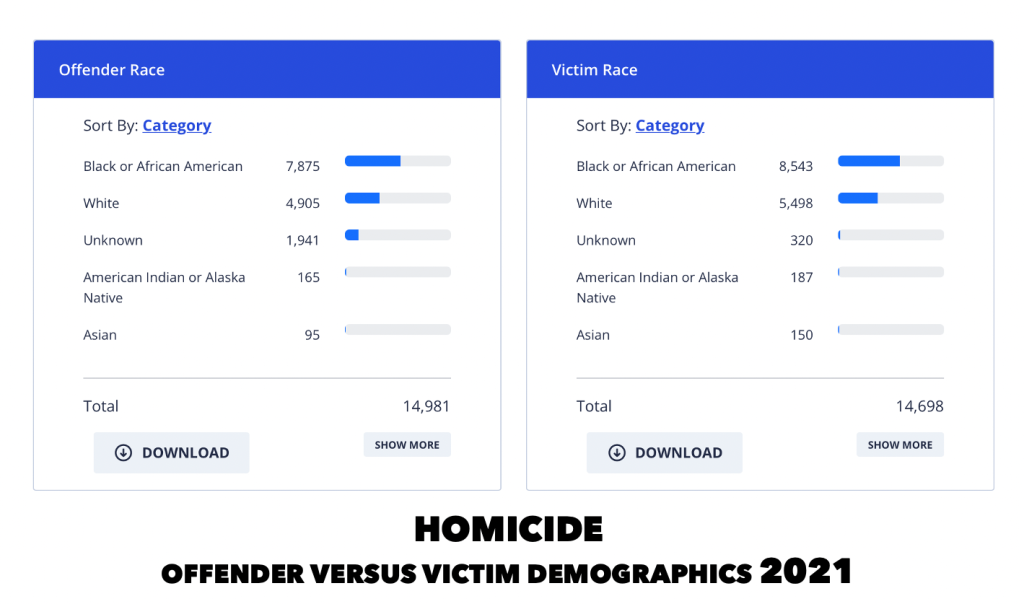

Public safety is a quality-of-life issue. Serious crime falls hardest on the poor and working class, especially black and brown people. The most recent statistics on homicide find that 8,543 blacks were murdered compared to 5,498 whites. On the offender side, 7,875 murders were black compared to 4,905 whites. Consider that the vast majority of murderers are male and black males are only six percent of the population—black males are responsible for well over half of all murders, as well as account for well over half of the victims. Again, such prominent Democrats as Hillary Clinton are openly lying about all this by substituting for the statistics that condemn their policies irrelevant state-level statistics; serious crime is an urban problem. What else do we hear from them? Black lives matter. It doesn’t look like it, doesn’t it?

Source: FBI

Black males are drastically overrepresented in robbery offender statistics, as well, Here we see a different victim profile along both lines of race and gender. However, although there are more white victims of robbery than black victims—79,566 to 43,164 respectively), there are disproportionately more black victims of robbery relative to population. At the same time, on the offender side, 93,252 robbers were black compared to 44,946. These are the numbers that explain the disproportionality in black civilians in fatal police encounters—and why some studies find the unexplained bias actually running in the opposite direction from that claims by progressives.

Source: FBI

Progressives cannot claim to speak for working people while undermining public safety. Ask yourself, why aren’t the progressives who run these cities working to fix the criminogenic conditions that disproportionately affect the marginal communities under their control? Why are they depolicing knowing that doing so makes these communities more dangerous, especially for the most vulnerable? Do not reason and compassion demand that, instead of rationalizing the situation in a manner that perpetuates crime and misery, and falsely accuses cops of racism, that those who claim to speak for marginalized populations would work to identify and solve the problems plaguing black people, the problems of idleness, dependency, fatherlessness, and mass immigration?