In her 2016 book The War on Cops: How the Attack on Law and Order Makes Everyone Less Safe, Heather Mac Donald examines the “Ferguson effect,” a phenomenon identified in 2014 by St. Louis police chief Doyle Sam Dotson III following the police shooting of Michael Brown (the event spawning the myth and the slogan “Hands up, don’t shoot”). In a St. Louis Dispatch story (“Crime Up After Ferguson”), Dotson notes that police officers, cowed by popular antipolice rhetoric, had become reluctant to fully engage their duties, emboldening lawbreakers already encouraged by popular delegitimization of law and order. Mac Donald had first broached the subject in a May 2015 Wall Street Journal op-ed, “The New Nationwide Crime Wave.” She expanded her argument in The War on Cops.

The release of The War on Cops in the context of Black Lives Matter upset progressives, their anger manifest in mob action threatening Mac Donald’s person at Claremont McKenna College (five students were suspended in the aftermath), and disrupting an event at UCLA at which she was the featured speaker, both events occurring in 2017. Black Lives Matter, which began in 2013 after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin in 2012, had reached its zenith in 2016, but was still a powerful popular force on the identitarian left in 2017. As one can see in the embedded video, the passions are still young (albeit students continue to disrupt Mac Donald’s lectures).

At the time of the book’s release, while not enraged and rioting, I was critical of Mac Donald’s arguments, in particular her July 2016 op-ed “The Myths of Black Lives Matter,” published in the Wall Street Journal. In an op-ed published in Truth Out, “Changing the Subject from the Realities of Death by Cop,” and in a radio interview with Project Censored (out of KPFA Berkeley), I accused Mac Donald of diverting attention from killer cops by raising the perennial problem of black-on-black homicide. I have since changed my opinion about Mac Donald’s thesis, as well as the motive behind asking the public to take a look at intra-racial violence. The latter concern is marked by a shocking statistic: half of all homicides are perpetrated by blacks on other blacks, the perpetrator overwhelming male, with black males comprising only around six percent of the US population. Moreover, in the period Mac Donald researched for her book, despite a decades-long decline in the rate of homicide, the percentage change for black victims of homicide had increased in by more than 15 percent.

An analysis of police shootings published the same year as Mac Donald’s book calls into question the premise of Black Lives Matter (henceforth BLM). Roland Fryer’s 2016 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) paper “An Empirical Analysis of Racial Differences in Police Use of Force” finds that, while blacks are better than fifty percent more likely to experience some force in police encounters (adding controls that account for contextual and civilian behavior reduces these disparities), for officer-involved shootings, racial differences do not appear in the raw data. Taking into account contextual factors and civilian behavior does not change those findings. Fryer’s research challenges a popular argument concerning police-civilian interaction, namely the alleged phenomenon of “implicit race bias,” a type of cognitive stereotyping discussed at length in this regard in Charles Epp, Steven Maynard-Moody, and Donald Haider-Markel’s 2014 Pulled Over: How Police Stops Define Race and Citizenship, a book I assign to my advanced criminal justice students.

The classic treatment of cognitive stereotyping in criminology is Jerome Skolnick’s 1966 “A Sketch of the Policeman’s Working Personality,” which undertakes an examination of police subculture in the context of widespread rioting in America’s ghettos amid accusations of police brutality and authoritarianism. A chief feature of the occupation is a milieu of danger, Skolnick observes, and this milieu fosters the construction of “symbolic assailants,” idealized threat types routinely confronting the officer. Stereotyping under these circumstances is a cognitive practice reducing the complexity of potentially dangerous but ambiguous situations via heightened awareness of and attention to various signs, such as attitude, body language, and dress, that may indicate potential threats. It follows that phenotypic markers used in the social construction of race would play a role in this phenomenon. Stereotypes are learned from training, peer socialization, and the greater cultural landscape, as much as from experience. Acquired stereotypes shape threat perception. It is how, for example, an officer can claim to see a weapon when no weapon is actually present.

There are other problems with the BLM narrative, which I discuss in the essay The Problematic Premise of Black Lives Matter, but to stay with the subject of implicit race bias for the moment, Mac Donald usefully summarizes the literature on this problem in an article “Are We All Unconscious Racists?” published in the City Journal in fall 2017. She cites Joshua Correll, a psychologist at the University of Colorado studying police decisions to discharge their weapon, who finds that officers are slightly quicker to identify an armed black target as armed than an armed white target and slower to identify an unarmed black target as unarmed than an unarmed white target. However, Correll does not find that officers are more likely to shoot an unarmed black target than an unarmed white one. In other words, Mac Donald summarizes, “faster cognitive processing speeds for stereotype-congruent targets (i.e., armed blacks and unarmed whites) do not result in officers shooting unarmed black targets at a higher rate than unarmed white ones.”

With respect to the different reaction times, Mac Donald wonders whether that might be attributable to the fact that “black males have made up 42 percent of all cop-killers over the last decade, though they are only 6 percent of the population” or the fact that “individuals involved in the daily drive-by shootings in American cities are overwhelmingly black.” For Mac Donald these are rhetorical questions. Indeed, as noted above, according to the Uniform Crime Report, published by the FBI, black males are responsible for roughly half of all homicides in the United States. Blacks are similarly overrepresented in other serious crime, such as robbery and burglary. In light of these statistics, I argued in my essay “Mapping the Junctures of Social Class and Racial Caste” that it is not police racism that causes black overrepresentation in crime, but rather black overrepresentation in police statistics is a consequence of black overrepresentation in the types of crime on which the police focus.

Even more damning to the implicit race bias claim than Correll’s failure to show that indications of bias explain police decisions to shoot civilians is Washington State professor Lois James’s finding that officers waited longer before shooting an armed black target than an armed white target and, moreover, were three times less likely to shoot an unarmed black target than an unarmed white target. James hypothesizes that, because of the contemporary racial climate surrounding policing, officers second-guess themselves when confronting black suspects. This finding provides evidence for Dotson’s Ferguson effect. Reflecting on his findings, in the NEBR research noted earlier, Ronald Fryer theorizes that the consequences of shooting suspects are sufficient to deter police officers from doing so to an extent that obviates any racial bias they may harbor.

It was more than merely digesting the research that supports Mac Donald’s argument that changed my mind (although, perhaps that should be sufficient). More broadly, I have reconsidered my attitudes about law and order in light of my humanist and socialist values. Thus readers will be happy to know that I have not jettisoned my leftwing values in this reconsideration but instead have more sharply focused them. I revisited the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, as well as those of the left realist approach in criminology, where I was reminded of my true choice of comrade—the proletarian worker—and the power of the historical materialist methodology.

This reappraisal led me away from the left idealism that underpins critical criminology (I have long identified myself as a critical criminologist) and towards a standpoint emphasizing the preconditions for decent communal interactions that indicate the need for the police function in a complex society—that is public safety. This standpoint is reflected in the scholarly and popular contributions by the proponents of left realism, to whom readers will soon be introduced, if they do not already know of them. I differentiate these perspectives in this essay and suggest a practical way forward on the vital challenge of meeting the security needs of working class families, one that involves engaging the work of secular conservatives such as Heather Mac Donald. Academics and policymakers must confront the alarming rate of homicide in black communities, for therein lies the explanation for crime and violence.

To this end, I argue, the left should cease rationalizing inner-city violence by reducing action solely to abstract social structure. The left treats black street criminals as if they have no or diminished agency, as if they have no or retarded capacity to choose not to violate the rights of others, as if they are not or lesser moral beings. I hear in contemporary leftist rhetoric echoes of elite white paternalism and black infantilization. I hear, “They can’t help it.” Moreover, progressives feed the public the lie that the problems of the black community are the result of white privilege and systemic racism, rhetoric that breeds race resentment and hatred rather than promotes the class solidarity necessary for changing the structures associated with the criminogenic conditions that disorder communities and breed interpersonal violence, what the realist Marxist literature describes as a process of “demoralization.”

Situating crime and violence in the desperate conditions of urban life under capitalism helps us understand why many feel they have no stake in conforming to the fundamental moral rules of decent human interaction. But it does not follow that the victims of criminal violence, disproportionately black residents of affected neighborhoods, are receiving their just deserts. This is at least of the implications of the rhetoric. In this, the left is engaged in its own version of victim blaming. Orthodox Marxism is in contrast unkind to those who respond to immiserative and oppressive conditions with interpersonal violence, making clear the correct choice of comrades. Progressive rhetoric, by denying or downplaying human agency, the result of reducing individuals to suspect abstract categories, substitutes for collective political action frustration and helplessness. Because of its failure to work from a class analytical framework, and instead from its penchant for putting race matters central to its politics, progressivism is not a way forward.

* * *

This past June, I noted on Freedom and Reason that the country received some good news in this year’s Uniform Crime Report by the FBI. After increases in crime and violence during 2014-2017, rates of murder, robbery, and aggravated assault—as well as rates of burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft—all declined in 2018. I noted in that entry that rates dropped in cities of all sizes, covering 300 million Americans, and in all regions of the United States. I cautioned readers that it is too soon to tell whether the country is back on track with the record declines it enjoyed in the many years prior to 2014, but the news was welcome, as less crime is good for working people, especially those who live in high poverty areas.

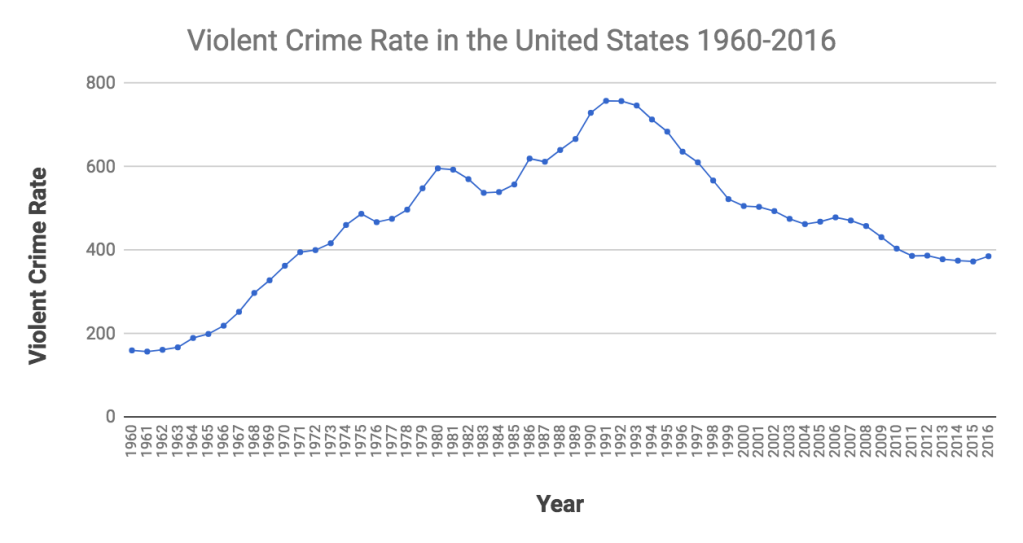

I amend those observations here with the bad news that, despite the improvement in crime rates in the short term, America’s central cities continue to suffer from unacceptably high rates of violent crime. This fact makes the problem of popular action against law and order a pressing matter. Indeed, it is the significant increase in serious crime occurring during Barack Obama’s second presidential term that moved Mac Donald to produce The War on Cops. “The crime surge is reversing a two decades long decline,” she laments, “during which American cities vanquished a 1960s-era notion that had made urban life miserable for so many.”

Mac Donald identifies a line of thinking on the left that emerged in the 1960s that high rates of crime were “a symptom of social failure in the governmental neglect, or even an understandable expression of protest.” In this view, crime was the predictable result of “poverty and racism.” Mac Donald refers to this line of thinking as the “root causes” thesis and notes the New Left’s claim that “routine behaviors such as walking down the street, going to a park, or operating a store would necessarily remain fraught with fear and the possibility of violence” until society roots out the causes of crime.

Sixties radicals portrayed law and order—cops, courts, and corrections—as an element in the structure of oppression that perpetuates the criminogenic conditions of urban areas; the targeting and unequal treatment of racial minorities represented the authoritarian reflex of a racist society. In their view, it followed that reforming and curtailing the institutions of police, prosecution, and prison were necessary steps for achieving social justice. “Under the influence of this ‘root causes’ conceit,” Mac Donald writes, “acres of city space were ceded to thieves and thugs, to hustlers and graffiti artist. Disorder and decay became the urban norm.” Thus the result of liberalizing the criminal justice process was a drastic rise in crime and violence, which a review of Uniform Crime Reports from that period confirms, as least on the basis of police reports.

In patterns possibly reflecting the rhythms of American capitalism, rates of crime, especially criminal violence, increased drastically during the 1970s and remained high throughout the 1980s and into the early 1990s, at many points reaching record levels (see chart below).

The problem of crime in the post-civil rights period sparked a long national debate about the validity of the progressive domestic policy approach that had marked US politics in the post-WWII period. I will leave the details of that literature to one side and focus instead on a book published at the peak of violent crime in America that attempted to identify the character of the debate, Cornel West’s 1993 Race Matters. In this book, West distinguishes “conservative behaviorists,” i.e. those who emphasize cultural factors and personal responsibility, from “liberal structuralists,” i.e. those who identify patterns of economic inequality and occupational and residential segregation. Both suggest governmental solutions to the problem (police and prisons for the former, reparations and social welfare for the latter). However, in West’s view, both sides miss the core source of the problem, namely the nihilism eating at the heart of the black community, a condition evidenced by a widespread and profound personal despair and sense of collective worthlessness. For West, the problem of inner-city crime and violence is an existential one, brought about by a complex of historic and contemporary economic and social factors.

Falling into the camp of West’s “conservative behaviorist,” Mac Donald is too dismissive of the role structural inequality plays in weakening the moral integrity of urban areas. She has her own “root causes” thesis: urban crime is ultimately the result of the breakdown of the black family structure and the emergence of an oppositional culture that rejects bourgeois values of achievement, community, and lawfulness. There is something to this argument. However, ideological myopia notwithstanding, Mac Donald is right to criticize the standpoint—West’s “liberal structuralist”—that depicts inner city criminals as victims of racist oppression and therefore less accountable than others for wrongful action. Moreover, Mac Donald and I would agree that the claims of the New Left, however much empirical support they may enjoy, provide no cause for the police to stand down in the face of criminal violence.

Suffice to say, Mac Donald’s account—that the 1960s-era trend in depolicing and decarceration are implicated in rising crime rates—is compelling. And, in the end, the conservative behaviorists won the debate. By the 1990s, Democratic Party nominees for president and vice-president, Bill Clinton and Al Gore, built their 1992 campaign around promises to “get tough on crime” and “end welfare as we know it.” Perhaps in a cynical effort to secure a political base, Democrats moved to the right on social issues, explicitly preying on public anxieties about public disorder. They were a different kind of Democrat, they said in campaign stops marked by youthful energy. In high-profile media events, Clinton would break from campaign trail to return to Arkansas, where he was governor, to sign death warrants for condemned prisoners.

The rightward shift in the Democratic stance on crime was in part attributable to the fact that Republicans routinely polled high on the issue of crime, finding widespread popularity with conservative “get tough” policies, despite the failure of such policies to curb crime over their twelve years of executive power. Policy shifts in the Democratic Party also reflected the movement of the world economy towards open markets: a reaction to the social disintegration wrought by transnationalism. Identifying and controlling deviance was an ideological tool for maintaining social control at home, putting the finger on the usual suspects, polarizing public opinion, and marshaling popular support for a police state.

Crucially, the Democrats’ legislative initiative and policy changes built upon a foundation already established. “Starting in the late 1970s,” writes Mac Donald, “legislators demanded convicted criminals serve more their sentences; habitual felons were finally locked up for lengthy prison stays.” She contends that “police leaders challenged the ‘root causes’ concept with a countervailing idea: the police could actually prevent crime and in so doing we make civilized urban life possible again.” Mac Donald thus credits the historic drop in crime and violence the nation has enjoyed over the last two decades to the bipartisan expansion of the criminal justice apparatus and an emphasis on law and order. The cause of the historic drop in crime and violence is a complex of cultural trends, social forces, and law and policy changes. The emphasis on law and order certainly played a role.

* * *

As I have been arguing, there is a lot to the historical account Mac Donald presents. However, typically missing in theories about the combination of forces that led policymakers to reassert law and order is the role played by a community of criminologists in Great Britain that—from the left—bolstered Thatcherite law and order politics from the right. Among the founding works are Ian Taylor’s 1982 Law and Order: Arguments for Socialism, Jock Young and John Lea’s 1984 What is to Be Done About Law and Order, and Richard Kinsey, Lea and Young’s 1986 Losing the Fight Against Crime. (See “Marxist Theories of Criminal Justice and Criminogenesis” for an overview.) Their realism stood in stark contrast to the idealism of the New Left, represented the critical criminologists, such figures as Richard Quinney, William Chambliss, and Stephen Spitzer. Quinney’s 1970 The Social Reality of Crime arguably defined the genre. “Crime,” Quinney writes, “is a definition of human conduct in a politically organized society,” one characterized by segmentation and power asymmetries.

The message of the critical approach to understanding crime was for the police to stand down and for states to empty their prisons, as these represented the machinery of capitalist oppression. However, the left realist had not been seduced by Europe’s post-Marxist (postmodernist, poststructuralist) turn, articulated by such flamboyant French philosophers as Michel Foucault, or the social constructionism of sociology’s phenomenology school, represented by Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann, methods that were increasingly dominating humanities and social science curricula of the nation’s universities. In contrast, the left realists reached back to the foundation of historiographical and social scientific thinking about the problems of inequality and disorder, ground tilled by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the founders of the materialist conception of history, or historical materialism. I next turn to a summary of this foundation.

* * *

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels refer to the lumpenproletariat—usually translated as the “dangerous class”—in these rather derogatory terms: “the social scum, that passively rotting mass thrown off by the lowest layers of the old society.” (Marx and Engels anticipated the fascist method of recruiting from the most impoverished segments of the proletariat the disaffected to serve as instruments in authoritarian action.) They admit that the lumpenproletariat “may, here and there, be swept into the movement by a proletarian revolution,” but that the conditions under which they live “prepare it far more for the part of a bribed tool of reactionary intrigue.” The lumpenproletariat was thus identified as a problem not only for capitalism, but for the working class. Engels had earlier detailed proletarian life chances in Manchester in his 1845 The Conditions of the Working Class in England. There he identifies a segment of society excluded from the labor market, burdened by a low social status, lacking class consciousness, often hostile towards other members of his species. There was in this analysis recognition of the desperation that accompanies economic deprivation. Without a stable source of income, the lumpenproletariat turned to illegalities to survive. Thus crime results from deprivation.

What are we to make of these frank and rather harsh observations from the master theorists of the proletarian movement? In light of Engels’ portrait of city life—abject poverty, neighborhood overcrowding, substandard housing, vice industries and their corrosive effects (alcohol, gambling, prostitution)—the lumpenproletariat should be seen as those constituents of capitalist society alienated from mainstream normative expectations. This is the criminogenic link between structural inequality, life lived beyond the discipline of the workplace, and the social problems that fall to the state to police, an institution established to manage the dangerous class and the general disorder inequality systematically generated. Engels writes in the Conditions of the Working Class of the problem of a demoralization in which a stake in conformity is lost due to estrangement from hegemonic bourgeois and upright working-class values. The attitude of what-do-I-have-to-lose proves the inadequacy of the capitalist state to provide the preconditions for normal human existence.

In a 1853 New York Tribune article “Capital Punishment,” Marx rejects the theory of punishment presented by German idealists and instead blames crime on the societal conditions. At issue is Kant and Hegel’s contention that by depriving the victim of his rights, the criminal abdicates his own. Quoting Hegel: “Punishment is the right of the criminal. It is an act of his own will. The violation of right has been proclaimed by the criminal as his own right. His crime is the negation of right. Punishment is the negation of this negation, and consequently the affirmation of right, solicited and forced upon the criminal by himself.” However, Marx argues that, while this formula respects the criminal as a human being by honoring his agency, it does not provide an account of the criminal’s mental state and action. It is not, therefore, an explanation. The introduction of free will into criminal responsibility thus treats the problem abstractly rather than concretely. In doing so, society holds itself innocent of the conditions that ultimately cause crime, of the situation that systematically generates the criminogenic forces that imperil public safety. Society’s innocence perpetuates the status quo, and the status quo is criminogenic. Marx condemns a society that finds no other recourse against crime but the punishment response.

However, Marx and Engels do not romanticize the criminal in the manner of the left idealist. “Primitive rebellion”—a reaction to one’s conditions without any theoretical or authentic proletarian consciousness to guide it—is, as Marx and Engels make clear in The Communist Manifesto, a problem for working class politics. In The Conditions of the Working Class in England, Engels writes that of the many forms rebellion can take, “the first, the crudest, the most horrible form” is crime. Marx and Engels recognize that there were other avenues for paupers to change the conditions of their existence besides crime. They could, for instance, organize themselves politically for collective action (such as the Black Panther Party). So that, while the conditions explain it, they do not absolve society of the need to deal with it. Crime as an atomized revolt against the conditions of capitalism imperils those who should be the criminal’s comrades. Criminals are not working class heroes.

* * *

Fast forward to the recent past where we find left realism, having grown in favor alongside the Thatcherite mood, proving influential on the New Labor government of the mid-1990s (Tony Blair and Gordon Brown), which pursued a third way in accord with the New Democrats of the United States (the latter a “movement” organized by the Democratic Leadership Council, established in 1985, and the “radically pragmatic” Progressive Policy Institute, established in 1989). As with Clinton’s crime bill, New Labor’s 1998 Crime and Disorder Act promoted stiff punishments for wrongdoing while also going after the alleged problem of “social exclusion,” the view that denials of the opportunity to prosper and thrive is associated with higher rates of crime and violence, which in turn deters investments in communities that could address the problem of poverty and unemployment.

Jock Young was not convinced of this thesis, popular among Tories. For Young, the secular climb in crime rates defied an easy economic explanation. Young was skeptical of the deprivation thesis and instead latched onto Merton’s notion of anomie (or classic strain theory) that saw street crime produced in the disjuncture of cultural desire and structural means. It was not that those who committed crime did so because they existed outside mainstream culture, but rather because the structure of capitalist society was criminogenic. In his miserable state, the primitive rebel comes to see his antagonist not as the capitalist mode of production that fails to provide the means for his desire, but social control agents and rivals in his community—educators, police officers, gang members—who are oppressing him. His limited consciousness leaves him vulnerable to the lure of rhetoric blaming his circumstances on actors in his environment not on the structure of his situation.

The contemporary rhetoric of racial victimization and “white privilege” gives permission to some of those who struggle in these conditions to blame their problems on his brothers and sisters who do not suffer his situation but nonetheless his class position, workers living and working beyond the inner-city streets, fences, overpasses, and walls that corral the descendants of slaves, share croppers, and migrant agricultural workers. They do not see others exploited by the same system, but rather view them with resentment. Such rhetoric fractures the working class, dragging the worker’s attention away from his class problem and towards the identitarian politics of imagined communities—those of ethnicity, race, and religion—preparing him for retaliation against perceived antagonists, which most often includes those in his immediate environment. The street criminal disrespects public safety because he perceives authority as the cause of his misery and so he disrespects authority and its associated normative demands. This, combined with crime and violence as available sources of economic opportunities (the process of criminal embeddedness), according to criminologist John Hagan, “play a role in maintaining the inner city on the moral, as well as physical, periphery of the economic system.”

* * *

Claims of racial oppression fuel rebellion and resentment while misidentifying the actual enemy. The rebellion is primitive because its source (structural inequality) is real, but its solution (scientific class analysis and collective political action on this basis) lies beyond its consciousness. Tribalism stand in the place of praxis. As a consequence, the lumpenproletariat visits his anger and frustration upon his brothers and sisters instead of their common oppressor, and makes trouble for those who are tasked with improving the public safety of his neighborhood. This was illustrated with the demise of the Black Panther Party, as I discuss on my blog in “The Black Panthers: Black Radicalism and the New Left.” There I write about how the shattering of the truce the Panthers had negotiated among street gangs saw the gangs soon devolving to the self-destructive tradition of continual warfare. “With inner city conditions rapidly deteriorating amid the mounting crisis of late capitalism,” I write, “gang violence escalated over the next two decades.”

Poverty and its manifestation in tribal thinking and primitive rebellion are corrosive to class solidarity. Today, the identitarian left, the BLM progressive, contributes to the fracturing of the working class by pitting the lumpenproletariat against those forces whose function is to secure his would-be comrades from crime and violence. Left idealism harbors the sentiments of anarchism; it dulls the instruments of the proletariat, that is the machinery of the state, the legal structure that can provide the legitimate preconditions for adequate life, by attacking the legitimacy of the state-itself. From a left realist perspective, the fact that the lumpenproletariat takes out his anger and frustration on other members of the proletariat is not lost in an idealism that forgets the importance of class struggle over identity—i.e. ethnicity, race, religion—and the role that functioning government plays in improving the conditions of the working class, the true source of aspirations and access to the juridical and legal instruments to achieve those aspirations.

Left idealism reflects a culture that disrespects the values of the enlightenment, of liberalism and secularism, dismissing these as “bourgeois values,” and substitutes for them values that leave the central city dweller receptive to reactionary intrigue that comes not from the fascist right but from the progressive left. Meanwhile, there is a leftwing politics that would use the state to restore order to cities and produce an environment where workers of all ethnicities, races, and religions could come together and struggle collectively for a democratic socialist order. The question for the left is whether the tools of law and order should be ceded to rightwing authoritarians who would use them for purposes of entrenching capitalist power—or whether they should be used by the left to take political control of working class communities.

* * *

New York City mayor Rudolph Giuliani and police commissioner William Bratton were advocates of “broken windows policing,” a theory advanced by James Q. Wilson and George Kelling in the March 1982 edition of The Atlantic. Their thesis was that tolerating forms of disorder as graffiti, litter, public drunkenness, and rundown property signals that social control has collapsed. This thesis was reinforced by the observations of Harvard sociologist turned policymaker and politician Daniel Patrick Moynihan in a widely reprinted article “Defining Deviance Down,” first published in a 1993 issue of The American Scholar, in which he contends that treating non-serious offenses less seriously signals that serious offenses are not as serious. He writes that American society has “become accustomed to alarming levels of crime and destructive behavior.”

Government response to crime seems to have had a positive effect. The success of New York City in reducing crime saw “broken windows” become a model for other American cities. The drop in crime, Mac Donald contends, “revitalized cities across the country.” “The biggest beneficiaries of that crime decline with a law-abiding residents of minority neighborhoods,” she writes. “Senior citizens could go out to shop without fear getting mugged. Businesses moved into formally desolate areas. Children no longer had to sleep in bathtubs to avoid getting hit by stray bullets. And tens of thousands of individuals were spared premature death by homicide.” All this is true. Crime rates plummeted after the passage of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994.

* * *

In contrast to the narrative that portrays the criminal justice system as merely an apparatus for controlling the proletariat, as the machinery of oppression, what I have identified in this entry as left realism, the Old Left attitude attributes crime to the conditions of capitalism, such as relative material deprivation, political marginalization, and demoralization. For the left idealist, the notion of a dangerous class is ideology. For the left realist, capitalism underpins conditions that are dangerous for working class people. Left realism is a response of the New Left’s failure to consider the suffering of working class at the hands of these dangers and for letting the right to monopolize law and order discourse.

To be sure, the left realists are not in the same camp as Mac Donald and her ilk. Mac Donald does not blame capitalism for the problem of crime and disorder. At the same time, the left realist argues for measures associated with conservative criminal justice policy. “Environmental and public precautions against crime are always dismissed by left idealists and reformers as not relating to the heart of the matter,” Lea and Young write in their 1984 What is to be Done About: Law and Order? “On the contrary, the organization of communities in an attempt to pre-empt crime is of the utmost importance.” What Heather Mac Donald’s The War on Cops brings into view is the failure of left idealism, and of leftwing progressivism generally, to grasp the need to reclaim the principle of law and order for the working class. It reminds us of our choice of comrades (I am borrowing this phrase from Ignazio Silone 1955 essay in Dissent).

Finally, Mac Donald registers concern over the future of the legitimacy of policing in the eyes of those who are most likely to encounter the police. In the preface to the paperback edition she writes, “Social norms, the legitimacy of authority, the rule of law—all are denigrated as the machinery of oppression, and the police are tarred as the most conspicuous embodiment of American injustice.” Elsewhere, she writes, “However much the recent crime increase threatens the vitality of American cities—and thousands of lives—it is not, in itself, the greatest danger in today’s war on cops. The greatest danger lies, rather, in the delegitimization of law and order itself.” “Riots are returning to the urban landscape,” she laments. “Police officers are regularly pelted with bricks and water bottles during the course of the duties.”

Antipolice rhetoric, especially the claim that policing is a manifestation of white supremacy, emboldens some members of society to be unjustifiably defiant. “Black criminals who have been told that the police are racist are more likely to resist arrest, requiring the arresting officer to use force and risk an even more violent encounter,” Mac Donald writes. This is not just a problem in inner city ghettos; anarchists in cities with progressive mayors are on the move, becoming more aggressive since the publication of The War on Cops, political elites telling commanders to order their officers to stand down.

“If the present lies about law enforcement continue,” writes MacDonald, “civilized urban life may once again break down.” While this may sound like hyperbole, the cost to those who live in neighborhoods where this attitude is prevalent suffer nonetheless. And it makes policing more dangerous. And that makes the police more dangerous.