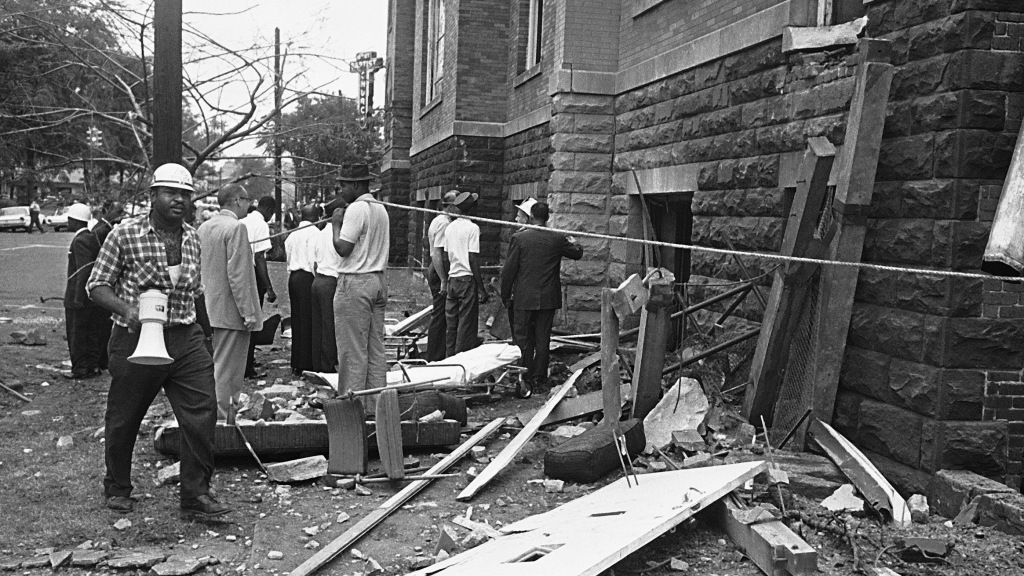

“Four little girls were killed in Birmingham yesterday. A mad, remorseful worried community asks, ‘Who did it? Who threw that bomb? Was it a Negro or a white?’ The answer should be, ‘We all did it.’” This was said on Monday, September 16, 1963, by a young Alabama lawyer named Charles Morgan Jr., a white man, who stood up at a lunch meeting of the Birmingham Young Men’s Business Club and delivered a speech about race and prejudice.

This is the theme of Andrew Cohen’s 2013 Atlantic essay, “The Speech That Shocked Birmingham the Day After the Church Bombing.” He claims that Morgan was forever shunned for saying this. While I do not support forever shunning (any length of shunning, actually), Morgan does deserve severe criticism for making such an argument. For it is not everybody who did this. The people who threw the bomb did this. They alone are to blame. We know it was four members of a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan who committed this crime. They were tried for and convicted of the murders.

If the argument is that those who bombed the church did so because of anti-black prejudice, and that, since anti-black prejudice is socially conveyed, we are all responsible for prevailing social conveyances, then the argument still fails, since, while anti-black prejudice may indicate the bomber(s) motive (I think it does), and thus explain the bombing, and while we should condemn anti-black prejudice (although there is no required for individuals to do this), the fact that the prejudice was learned can in no way implicate society in the act, since individuals either choose to perpetrate wrongdoing or they are not responsible for their actions. Actus reus requires that an action is voluntary to be a crime. Society is not a voluntary actor.

It’s rhetoric like Morgan’s that deranges the civil rights struggle. Civil rights becomes a quasi-religion at this point, replete with transcendent notions of collective and intergenerational guilt. That Morgan’s words echo down through history as if they bent the arc of the universe a little towards justice, as Cohen claims, tells us just how much popular understanding of justice has been shifted from one of rational adjudication of the facts to that of magical thinking and superstition. Because we all know that belief in collective guilt is widespread in American society.

This way of thinking is easy because it happens in the context of a culture of believers. Because of ubiquity of religious thinking in the United States, the majority is primed to believe in such magical and superstitious notions as collective guilt, to see individuals whose behavior is not directed by an organization as belonging to abstracts grouping that do direct their actions. Thus, without a directive or chain of command, by virtue being in society, the individual is responsible for actions taken by others. This is the irrational basis of such constructs as white privilege and the demand for reparations.

Those who believe in the supernatural expect to see ghosts—to be haunted by them. They are prone to accept claims that root in the spirit realm of sin and salvation. None of this is true, of course. But, in any case, none of this can be part of a secular system in which religious belief is the prerogative of the individual but the obligation of none. We see in Morgan’s speech (much of which is reproduced in Cohen’s essay) the logic of critical race theory. Critical race theory, a quasi-religious system, eschews the burden to prove intent. And we should shun critical race theory.