Government is obliged to make law, policy, and judgments without regard to race unless the purpose is remedying a situation of race-based discrimination. Race is regarded as a “suspect classification,” that is a class more likely subject to discrimination, and thus considerable only under very narrow circumstances or “strict scrutiny.” Standing law regards race as comprised of inherent, significant, and recognized phenotypic traits, such as skin color, eye shape, and hair texture. Legal principle allows courts to consider redress for those racial classes disadvantaged historically or marginalized in the political process This is obviously a complicated affair.

To count as discrimination, an action must lack a rational basis and violate the principle of equal protection, meaning that a governmental or analogous body may not deny persons equal treatment under the law. Put another way, a public agency must treat concrete individuals similarly in similar circumstances. The doctrine of “separate but equal” as a regime to get around the Fourteenth Amendment was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1954 because individuals were treated differently in public facilities formally segmented by race. A decade later, Congress extended equal treatment to public accommodations; businesses were barred from discriminating against customers and workers on the basis of race.

Because race is a social construct and not a biologically-discernable reality, demands that race-as-class exist as a discrete entity, that it exist as separate and distinct enough to determine who belongs to a particular race and who doesn’t, complicates matters. How do you really know whether a person is really a member of a particular race? The principled way is to demand equal treatment without determining whether the offended part is “actually” a member of a racial minority. Everybody is treated as individuals. However, governments have sought to entrench and perpetuate discreteness by codifying elements of racial identity. Here, the state defines race into existence by drawing subjective boundaries around a phenomenon that has no natural or objective boundaries.

For example, for some time in the United States, governments operated according to the “one-drop rule,” which classified persons with any sub-Saharan African ancestry as “black.” A similar blood quantum rule was devised for determining American Indian heritage. The biological or constitutional definition represented the conception of race established by racism, an ideological system holding that the human species can be meaningfully divided into subgroups that are predictive of cognitive ability, behavioral proclivities, and moral aptitude. The rules have been abandoned. But with modern DNA testing, and the push for reparations for certain minority groups based on historical injustices and justified by intergenerational and collective guilt and victimhood, one can imagine a new regime of blood quantum to determine worthy recipients from redistributed resources.

As I have blogged before, a political effort is underway, one buttressed by the postmodernist turn in the social scientific enterprise (giving ideological work the appearance of objectivity), to expand the definition of race to include traits not historically or legally recognized as such. I show these essays how, in the eyes of those advocating for the expansion, prejudice and discrimination based on biological or physical traits is respecified as “biological racism,” while emphasizing that prejudice and discrimination takes another form, that of “cultural racism.” (One problem with this is that the enlargement of the definition allows progress in race relations to be trivialized in light of the new racism society must overcome, a problem I take up in some of these entries.)

Thus, in addition to the historically and legally recognized definition, the definition of race is expanded to include fashion, hair styles, and other cultural features, even accents, comportment, and grooming practices. This is the source of this notion of “cultural appropriation,” an racist offensive in which somebody of the “wrong” race adopts the fashion or hair style of the race who claims exclusive access to fashion or hair style (or music, art, etc.). This politics means to keep racial groupings discrete by policing cultural and ethnic borders. In light of the perceived inadequacy of informal social control in the task of boundary maintenance, the movement demands the government do the work of racially segmenting society by defining race in particular ways. Thus we find ourselves in a period of re-racialization.

One might think that the practice of classifying racial groups is what society sought to do away with when it criminalized race discrimination and debunked theories purporting to explain culture on the basis of race. But one risks perpetrating “colorblind racism” for saying this. To be sure, during the civil rights movement, racialization was a negative thing to overcome. Martin Luther King, Jr. dreamed of a day when people would be judged by the content of their character and not the color of their skin. Nowadays a person may be presumed a conservative for embracing the colorblind ideal. For post-civil rights progressives, racialization of populations is a positive thing, a necessary step in achieving social justice. Embrace difference and back it with the force of law.

Let’s be frank about this. With the reification of the social construct of race that comes by officially defining its attributes, then seeking to redistribute things on that basis, by privileging concrete persons on the basis of group identity, individual rights gives way to group rights. Put another way, claims of reparative justice require careful delineation of who can claim group membership and what freedoms and resources one can therefore express, possess, and access on this basis. This requires racializing the population in new ways.

* * *

In a June 17, 2011 Guardian article, “School’s refusal to let boy wear cornrow braids is ruled racial discrimination,” we learn that the high court of London ruled that school authorities must consider allowing boys to wear cornrows if it is “a genuine family tradition based on cultural and social reasons.” To be clear, the ruling did not allow boys to wear cornrows. It allowed only some boys to wear cornrows on the basis of cultural and social reasons. This means that those boys who wanted to wear cornrows for their other reasons were not permitted to do so.

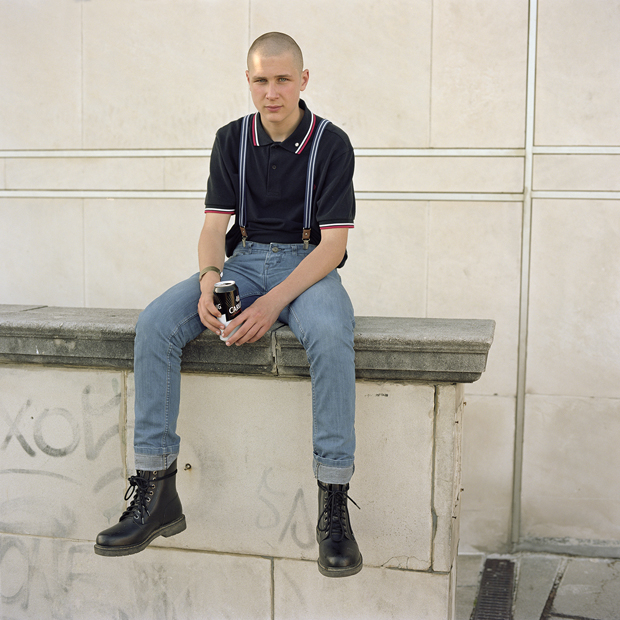

The headteacher, Andrew Prindiville, of St. Gregory’s College, justified the school’s hair policy—“short back and sides”—as necessary to suppress gang culture. Haircuts are used as badges of gang membership, he said. The judge, Mr Justice Collins, said that cornrows were not necessarily gang-associated. Other styles, such as the skinhead, might well have that connection, he said. Emphasizing that the school’s hair policy was lawful (why?), the judge declared that exceptions had to be made on ethnic and cultural grounds (why?). The judge noted that exceptions were already made for Rastafarians and Sikh boys who wore their hair below the collar (why do past errors validate present ones?). Why should it be any different for African Caribbean boys? The boy’s solicitor, Angela Jackman, said, “It makes clear that non-religious cultural and family practices associated with a particular race fall within the protection of equalities legislation.”

We can see in this case the manner in which the definition of race is being expanded to include non-phenotypic features, namely presumptively exclusive cultural and social attitudes and habits. We also see in the rhetoric that attire and practices permitted for some boys denied to other boys on religious grounds is presumed as given.

To be clear, I don’t like what skinheads stand for. But the government should be content-neutral on such matters. Is skinhead not a cultural phenomenon? Is it not part of a tradition? Indeed, it is. Does a boy not have a right to wear a skinhead if he wishes? Or to hold racist views? Is it the now the government’s job to determine what are legitimate cultures and traditions? If everybody is allowed to wear their hair however they wish, then the state doesn’t have to make any exceptions at all. The government also gets to avoid discrimination based on race, ethnicity, religion, or whatever. That would be individual liberty at work. But, here, the court is acting on the basis of group rights. Members of one group have access to hair styles while members of another group do not. And this is offered as “justice.”

To be clear, it’s fine for people to debate what is or is not part of a ethnic identity (hence the tedium of “cultural appropriation”), but the government should not be in the business of determining what is appropriately ruled in or out of imagined communities the state does not and should not constitute. It is not for government officials to determine who is a legitimate member of this or that racial group or who can engage in a cultural activity. We can’t have the government policing such things.

What is more, culture is not race; so why are hairstyles, a product of (often fleeting) culture, even at issue? As I have demonstrated on my blog, race is constructed around socially-selected phenotypic features resulting from ancestry. At least there is some genetics there. For example, you could, using DNA, racially define subpopulations on the basis of ancestry (which would necessarily enter the problematic of hybridization). How one wears his hair is not a genetic trait at all. Neither is how one dresses. Is this a return to the nineteenth century notion that tattoos are an atavistic expression? And what would it do to make a skinhead wear a different hairstyle in any case? Or cover his tattoos.

Remember when people immediately recognized that the state defining who is and who is not this or that race was racist? Now we have the state including in the definition of race things that are not even part of the phenomenon. A court in Great Britain is officially racializing culture and privileging people on account of it. In this ruling, if a boy is the right race, then he can wear his hair in a differently prescribed way. But the principle of equal treatment demands that the government does not treat individuals differently on the basis of race. Angela Jackman’s distinction between religious reasons and non-religious cultural reasons is no distinction at all. It would be just as discriminatory to allow an exception for an individual on religious grounds that was denied an irreligious person. The codification of special rights on the basis of culture, race, or religion is antithetical to the pursuit of equality and liberty.

You may be thinking: “Well, that Great Britain. They’re not as bad as the French, but they have a very poor understanding of individual rights and personal liberty.” Unfortunately, the social logic of group rights is spreading in the United States. In early July of this year California governor Gavin Newsom signed into law the CROWN Act (Bill SB-188), which bans discriminating against “natural hair.” The act had passed both the California senate and the state assembly unanimously. The law expands the definition of race to cover culture. In doing so, it writes race-based discrimination into the law. Sociologist Chelsea Johnson, who studies the “natural hair movement,” speaks for many when she says that bill SB-188 is a “much needed first step toward protecting women of color’s rights to wear their hair in its natural state and according to common cultural traditions across the African diaspora.”

But what about protecting the rights of individuals of any color to wear their hair the way they wish? In taking issue with New York City’s Commission on Human Rights ruling that it will protect “the rights of New Yorkers to maintain natural hair or hairstyles that are closely associated with their racial, ethnic or cultural identities,” Stanford law professor Richard Thompson Ford, an expert on civil rights and anti-discrimination law, argues that hairstyle is not a civil right. “Moreover,” he argues, “the new hairstyle rights can’t apply just to minority groups. If black employees have a right to wear, say, multicolored braids or an ‘untrimmed’ Afro, then it follows that white employees have a right to wear unusual hairstyles associated with their race too, such as a messy shag cut, a regrettable 1980s style ‘Mullet’ or glam-rock teased hair.” “And who’s to say which hairstyles are associated with which races?” he adds. Indeed. In an early essay, Ford argues that banning dreadlocks at work is not racially discriminatory even if it should be illegal. “We could clean up this mess by simply establishing a legal right to autonomy in personal appearance,” he argues. In his 2006 Racial Culture, Ford argues that courts should give up on trying to figure out what counts as race.

I hasten to add that the natural state of hair of many white people falls within the domain claimed by some “people of color.” I had white friends in high school who wore afros. For them, the afro was the obvious choice. It’s where their hair wanted to go. And it allowed them to express their freaky selves. But what if a white boy wants to wear dreadlocks? Egyptians, Germanic tribes, Poles, Vikings, Pacific Islanders, early Christians, as well as the Somali, the Galla, the Maasai, the Ashanti and the Fulani tribes of Africa—all have worn dreadlocks. As University of Richmond professor Bert Ashe writes in his Twisted: My Dreadlock Chronicles, the better question is, “Who hasn’t worn dreadlocks at one time or another?” White women have kinky hair. So do white men. Will they be discriminated against if they wear dreadlocks or cornrows?

There is a disturbing development in all this. People don’t actually own culture. One can appropriate any cultural element they choose. Humans have been doing this for millennia. Yet, armed with identity politics, people are claiming cultural items, and they are doing so using the rhetoric of group rights. Does it not seem that the idea of cultural appropriation is a manifestation of the internalization of corporate branding. Black moral entrepreneurs are defining blacks as a corporate body. Remember how Rachel Dolezal—an “objectively” white woman—was attacked for defining herself as part of that corporate body? Islamic leaders have also declared themselves a corporate body. Both the postmodern and religious view of things is that identity is what determines the individual. These notions undermine personal freedom by sacrificing the individual on the altar of group identity.

“Natural hair” laws are easily repurposed to discriminate against whites who wear “black” hairstyles. If a court or a legislature declares dreadlocks a racial feature, and on this basis disallow businesses from demanding employee adhere to a dress code, then a person not of that race could be compelled to adhere to a dress code by cutting their dreadlocks. We already see this with religious accommodations. As I recently blogged on Freedom and Reason, school authorities tell my son that he can’t wear a hoodie at school, but the girl who subscribes to (or is forced to observe) the Islamic dress code can wear a hijab. Those who advocate such practices seem oblivious to the principle that makes religious discrimination wrong in the first place. The principle that decisions cannot be based on religion in such a way that gives members of a religious group the right to cover their heads but forbids individuals who do not belong to that religious group from covering theirs escapes the radical multicultural subjectivity. It’s sexist, as well. Girls can cover their heads, but boys cannot.

“This is not just about hair, it’s about acknowledgement of personal rights, it’s about checking bias,” says California State Sen. Holly Mitchell, a Democrat who wears dreadlocks and proposed “Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair” Act, or CROWN. Banning ethnic hairstyles “upholds this notion of white supremacy,” Patricia Okonta, attorney for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund says. She continues: “While there isn’t a consensus among federal courts about whether racial stereotypes violate Title VII, the federal law that prohibits workplace discrimination based on race, sex and religion, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund has argued that natural hair and styles should be covered by that statute.” The New York City Commission on Human Rights agrees. “The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc., has taken on several cases including one filed on behalf of two Boston-area sisters, Mya and Deanna Cook, who were forbidden to wear braid extensions to Mystic Valley Regional Charter School in 2017. The policy has since been rescinded.” The hair stylers are part of their authentic selves. Society must reject “Eurocentric beautify standards.” Alan Maloney won’t be refereeing high school wrestling matches for a while because he asked a wrestler to cut his dreadlocks or be disqualified. Despite the fact that dreadlocks can cause eye and other injuries, his ruling was condemned as racially discriminatory.

* * *

I had very long hair from much of my life. Many in my family hated my long hair because poor people have long hair. You know, white trash. I couldn’t get a job for years because I had long hair. People thought I wasn’t looking for work. But it was the hair. I did not want to give up my hair because businesses thought men should wear short hair. Cops targeted me for my long hair. They presumed I was a drug user. I cut my hair in my early twenties so I could eat and pay rent. I’m not proud of it, but I gave in. Poverty will do that to a person. I realized that my hair wasn’t as important as food. I didn’t have a “natural hair” movement to change rules and perceptions for me. I had to wait for attitudes to change. In time, I grew it long again. This was the most common conversation I had when meeting new people: “So why do you grow your hair? Is it a political statement?” No, I would answer, it’s always felt like part of my identity. (I did not act as if I was the victim of a microaggression.) I tell people I first grew it when I was 12-years-old. For some reason, nobody found that a compelling argument. Well, music and music shops and construction work gave me situations for time in my identity. Not my “group identity,” mind you. My identity. I am an individual. I am a person.