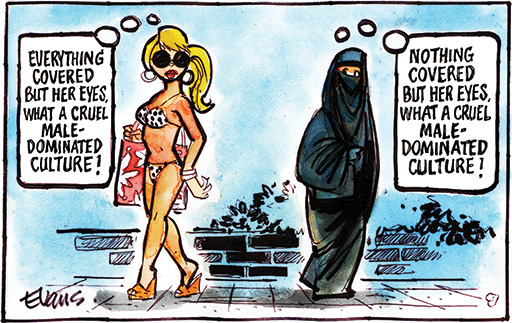

You’ve seen the memes, I’m sure. They convey a double standard on the part of unenlightened Westerners: How can Westerners condemn the burqa and the niqab, while tolerating the bikini? Progressives would have us wonder whether women in the West choose to show skin. There is no law requiring women to dress a certain way, but no law is needed, we are told; cultural imposition is a powerful force that shapes the way people appear to others. But is showing skin the result of the male gaze? For feminists, the patriarchy determines feminine and masculine appearance, and the role of women in patriarchal society is to be objects for men. So, yes, it is the result of the gaze.

The observation holds partial truth: culture shapes appearance and behavior. Yet applying the same scrutiny consistently would require examining veiling practices in many Muslim-majority contexts, where legal, familial, or social compulsion frequently limits genuine choice for women. But cultural relativism intrudes: outsiders must refrain from judging the culture of others, even as Western norms face constant deconstruction. The lens is one-way—Western norms equate to patriarchal imposition; non-Western ones represent authentic cultural expression, and we should be committed to the integrity of the latter. Universal women’s rights dissolve under this inconsistency.

For feminists, the question of who is forcing women to show skin in the West is answered: it’s male-dominated culture. Everybody is an object to everybody else, as Christopher Hitchens observed in a debate with feminists on The Charlie Rose Show in 1994. But objectification is misogyny, his interlocutors insisted. Women in the West internalize the expectations of a male-dominated society, then conform to those expectations. This is oppressive. But only in the West. One could with confidence expect that Hitchens’ criticisms of compulsory wearing of the burqa, chador, and niqab, had the subject come up, would have been dismissed as Islamophobic, had the 1997 report Islamophobia: A Challenge for Us All by the British think tank Runnymede Trust appeared earlier, and the charge socialized.

By the lights of what one might assume to be a coherent feminism, the burqa, chador, and niqab are likewise expressions of patriarchal culture. But here, the doctrine of cultural relativism intrudes. The doctrine convicts those who defend the rights of women as a universal principle of hypocrisy; the Western observer should not criticize the veil while it tolerates partial nudity in its own cultural space. Moreover, the Westerner must tolerate the veil in its midst. The universal principle must therefore be abandoned or ignored. This is the rot of identity politics.

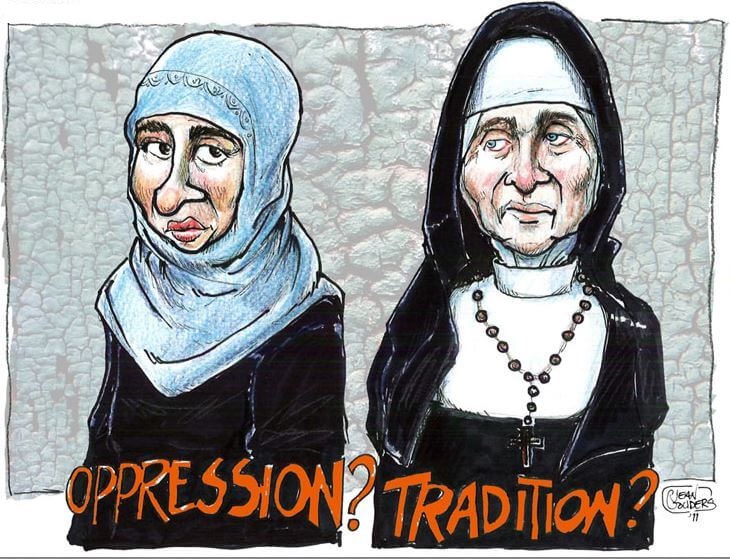

The hypocrisy sharpens in comparisons of the niqab to the Catholic nun’s habit. The above meme has elicited comments from me on social media on numerous occasions. My critique is as follows: A woman takes religious vows when she joins a religious order. These vows include poverty, chastity, and obedience. One of those vows is chastity, the commitment to lifelong celibacy, meaning the woman does not marry or pursue romantic relationships so she can devote her life fully to spiritual service. In another, the vow of obedience, she agrees to follow the rules of her religious order and the guidance of her superiors. But no Western woman is required to be a nun; thanks to the First Amendment, she is not obligated to follow the rules of any religious order. Moreover, the nun does not always appear in public in her habit. Equating voluntary, exclusive religious commitment in a pluralistic society to mandatory veiling for an entire gender class ignores a fundamental difference.

(As an aside, there is a paradox in the analogy if taken at face value; if Catholicism compelled such vows universally, the faith would vanish demographically within generations.)

Many progressive feminists condemn women internalizing the male gaze and conforming to sexualized ideals, yet defend compelled veiling in certain societies as a cultural or religious prerogative. Moreover, they champion bodily autonomy—except when it involves traditional feminine expression in the West, which must be interrogated—while attending or endorsing Pride events featuring men adopting exaggerated feminine stereotypes and explicit sexual displays (including non-simulated acts) in public spaces accessible to children. Women must avoid being sexy for dignity’s sake, but male nudity and graphic simulations, even enactments, of sex acts qualify as liberation.

Strangely, many progressive feminists mimic Iran’s version of the Guardian Patrol when they condemn what they suppose is the power of the male gaze in the West. But how can they be an adequate moral police, considering the debauchery of the Pride parades they attend and celebrate? Feminists object to women internalizing the gaze, yet they defend the compulsion to veil in many Muslim-majority societies by appealing to cultural relativism, as well as men donning the feminine stereotype (which a free and open society permits). More than this, they insist that we call these men women. I am not speculating. Just days ago, we observed that International Women’s Day was repurposed to advance trans rights.

It is telling that many progressives insist that men adopting feminine stereotypes and pronouns are women, while fundamentally redefining the very category that feminism claims to represent. On March 8, the United Nations observance centered on the theme “Rights. Justice. Action. For ALL Women and Girls”—a call to dismantle barriers to equal justice, including what is condemned as discriminatory practices and harmful social norms. In progressive advocacy spaces, events and slogans advanced queering culture, framing women expansively to encompass trans women alongside biological women. This fluidity applies when convenient for certain critiques but dissolves when asserting a transcultural, stable category of woman elsewhere.

Whatever one thinks of the veil or the transgressive acts of queer praxis, what is clear is that progressives don’t operate according to any sound principle. An adequate moral police, however objectionable such a thing is in a free society, should at least be principled. But cultural relativism cannot be principled, since it demands that a culture only judge itself, in this case, the treatment of women in Western patriarchal society, and here only selectively. Who are we to criticize how women under Islam are treated? If one does, it is a sign of chauvinism. It is not our culture, after all. It’s theirs, and in their culture, women go veiled.

Moreover, in Western culture, as progressives see it, women are not women as such. Gender, a cultural construct, is therefore also relative. There is no transcultural or transhistorical woman. Concrete women do not make a universal category. This is why, for the progressive, there is no answer to the question, What is a woman? At the same time, treating women as objects is only wrong in the West.

The standpoint is incoherent. Cultural relativism is no principle at all. It is, on the contrary, inherently unprincipled: it demands cultures judge only themselves, insulating non-Western patriarchy from external critique while subjecting Western norms to relentless scrutiny. Gender becomes a malleable cultural construct—except when treating the category of woman as a fixed, universal category, nonetheless used to condemn Western objectification. The question “What is a woman?” elicits no consistent answer, yet objectification is wrong only in the West. This is why asking the question is met with eye rolling and sighs.

Underlying this is more than anti-Western bias or fetish normalization. The selective drive appears aimed at eroding traditional male-female relations and the family as society’s foundational unit—but only in the West, and even here inconsistently. Non-Western gender oppressions, e.g., female genital mutilation, once a global human-rights priority, now elicit far less outrage; voices like Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who endured FGM and critiques such practices, face marginalization, while figures like Linda Sarsour, who chooses hijab and organizes in women’s advocacy, gain prominence. It all seems calculated to disrupt gender categories and relations.

Principled feminism demands consistency: equal scrutiny of any system that subordinates women through coercion—cultural, legal, or social. It cannot exempt veiling under compulsion abroad while problematizing voluntary feminine expression at home; it cannot champion bodily autonomy selectively or redefine the category woman to erase biological and historical reality while claiming to advance women’s rights. Relativism undermines the very idea of universal human rights, and therefore women’s liberation internationally. True feminism—if it is to be principled—cannot exempt certain cultures from scrutiny; it cannot defend veiling under coercion or cultural imposition abroad while condemning selected voluntary gender expression at home, nor can it champion bodily autonomy only when it aligns with dismantling traditional Western norms. Indeed, a principled feminism would not seek to dismantle those traditions at all, given that these are the traditions that liberated women.

In a free society, women should dress as they choose—revealing skin, covering fully, accentuating form—without coercion. Hair, makeup, and cleavage are cultural and historical expressions, not intrinsically patriarchal. Many Islamic contexts deny women this freedom through formal or informal social control, relegating them to second-class status. The result of double standards is not empowerment but incoherence: an ostensive moral framework that defends forms of patriarchy abroad and welcomes it in the West, while aggressively but selectively demanding its dismantling domestically. Selectivity is determined by identity politics, which is an expression of progressivism, the ideological projection of corporate statism. There is no sisterhood to be found here.

The Western progressive double standard and identitarianism ultimately serve ideological aims that do not include women’s universal dignity and freedom. Indeed, progressivism eschews universals, since these are obstacles to the operation of the corporate state. Even scientific knowledge is corrupted by the doctrines of cultural relativism and gender identity.

Let us suppose we no longer wish to live in the context of a negative dialectic as Theodor Adorno conceived it—that is, living with contradiction. In which way should these contradictions be resolved? In a free and open society, a woman should dress the way she wishes. If a woman wishes to show her skin in public, she should be allowed to. What’s wrong with showing skin? What’s wrong with accentuating the female form? In what way is hair, makeup, and cleavage—to be sure, cultural and historical—patriarchal? Is it not obvious that, in Islamic societies, women are not free, since women must obey the demands of a patriarchal culture, whether by formal or informal social control? Isn’t the treatment of girls and women in Islam not the paradigm of objectification, however much the claim is that concealing the feminine form protects women from the male gaze? I always thought feminism’s purpose was to dismantle the patriarchy. Yet, today’s feminists see the patriarchy where they want to.

To escape perpetual contradiction, feminism must reclaim universals: women constitute a coherent category; all deserve equality, freedom from coercion, and genuine bodily autonomy. Men may express gender freely, but cannot be women. Society cannot be compelled to recognize men as such. These are not arbitrary categories. Only uniform application of these principles—across all cultures and ideologies—can achieve real liberation for women, who comprise a scientifically demonstrable exclusive category, replacing selective indignation and ideological incoherence with principled advocacy for women’s universal dignity and freedom.