Note: I based the present article on a lecture I delivered to the United Nations University in Amman, Jordan in November 2006. The aim of the argument is to raise awareness among members of the international community about the role of Christian neo-fundamentalism, also known as Christian Zionism, in the development, marketing, and promotion of US foreign policy in the Middle East. I argue that material interests in Middle Eastern energy resources (namely oil), and the presence in government of neoconservatives, while clearly representing the major forces shaping the direction of US policy in the Middle East, are by themselves insufficient facts to explain military occupation of Iraq and the United States’ uncritical commitment to the state of Israel. What completes the explanatory picture is a study of what we might call the “Christianist” – that is, the Western counterpart of the “Islamist.”

In July of 2006, John Hagee Ministries of San Antonio, Texas, held its first annual conference of a newly founded organization, “Christians United for Israel.” Hagee Ministries is an evangelical Christian organization founded in 1987 that stands at the forefront of the countermovement Christian Zionism. Among other things, Hagee and his followers believe that the land of Israel never belonged to Arabs and that the people who call themselves Palestinians actually came from Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq and other Arab nations. (Hagee’s propaganda draws from Joan Peters’ 1984 book, From Time Immemorial (1984), which was exposed as fraudulent years ago by Norman Finkelstein in his 1988 study “Disinformation and the Palestine Question.” Deceit notwithstanding, Peters’ thesis has formed the core of Alan Dershowitz’s 2003 work, The Case for Israel, which Finkelstein debunked in his 2005 book Beyond Chutzpah.)

Standing before 3,500 evangelical leaders in Hagee’s church, the Israeli ambassador, Danny Ayalon, spoke of the close relationship between Christian evangelicals and the Jewish state. Christians, Ayalon said, are Israel’s “true friends.” The chairman of the Republican Party, Ken Mehlman, along with several Republican senators, also attended the event. During dinner, Hagee read greetings from President and Prime Minister Olmert, and then told the crowd to tell their representatives in Congress “to let Israeli do their job.” What job was he talking about? Wiping out Hezbollah in southern Lebanon. Hagee called the conflict between Israel and Hezbollah “a battle between good and evil” and then asserted that support for Israel was “God’s foreign policy” (“For Evangelicals, Supporting Israel Is ‘God’s Foreign Policy’”, The New York Times, November 14, 2006).

Widespread support of Bush and his foreign policy among evangelical Christians is rooted in events unfolding in the late 1960s-early 1970s—events surrounding nationalist politics and economic imperatives. Up until the 1960s, US oil industry, represented by mega-corporations such as Chevron, Exxon, Gulf, Mobil, and Texaco, controlled energy supplies in the Middle East. However, during the decades of the 1960s and 1970s, political and cultural movements in the Arab and Persian world led to progressive nationalization of the oil industry. Flexing its political-economic muscle in the wake of the 1967 war between Israel and its neighbors, and especially moved to action by the 1973 Yom Kippur Arab-Israeli war, the Arab oil states shocked the US economy with disruptions of supply, pushing energy prices higher and fueling inflation in the US economy. With these changes, the Middle East became a pressing priority for US politicians and the corporations that finance them. (The following summary of planned and actual US intervention in this section is indebted to a chronology developed by Robert Dreyfuss. (See “The Thirty Year Itch”, Mother Jones, March/April 2003.)

The Ford administration, with a policy team led CIA director George H. W. Bush, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and Chief of Staff Richard Cheney, developed a plan in 1975 to overthrow the Saudi government for the purposes of seizing their oil fields. Ford’s short term in office, and a lessening of the crisis in the mid-1970s, stalled implementation of the plan. However, the Iranian Revolution and Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, both occurring in 1979, moved President Jimmy Carter and Secretary of State Zbigniew Brzezinski to renew plans for military intervention in the region. In announcing the “Carter Doctrine” in 1980, Carter stated that any “attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force” (State of the Union Address, January 23, 1980). Carter declared that the Gulf would be a zone of US influence and created the Rapid Deployment Force (RDF), which stood ready to invade the Gulf region in case of crisis.

Under the Reagan administration, the RDF became The Central Command. Reagan pressured countries in the region, primarily Saudi Arabia and Turkey, to permit access to and development of military bases, support facilities, and forward staging areas. The US government sold billions of dollars’ worth of arms to the Saudis in the early 1980s. Central to policy development was George Bush, then vice president. The goal of militarizing the region was more or less completed with the first Gulf War when, under the direction of Bush, then president, and Cheney, Secretary of Defense, the US persuaded Gulf states to allow permanent military presence on Arab soil. In the decade that followed, the US sold more than 43 billion dollars worth of weapons and military construction projects to Saudi Arabia, and some sixteen billion dollars more to Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates.

Like Carter, the Clinton administration sought to enhance America’s favorability in the region by pursuing peace between Israelis and Arab; yet Clinton carried out strikes in Yemen, Pakistan, and elsewhere, as well as maintaining economic sanctions and no-fly zones over Iraq in a perpetual climate of war. This history culminated in the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in the second Gulf War, led by President George W. Bush, along with Vice President Cheney and Defense Secretary Rumsfeld.

To meet the needs of the growing American empire, the United States has spent trillions of dollars on military hardware and war operations. The military budget, which stood around 80 billion dollars in the mid-1970s, is projected to reach 440-plus billion dollars in 2007, not including supplemental appropriations. That’s an annual price tag greater than the combined budgets of the next fourteen largest militaries. Much of this spending is dedicated to maintaining a militarized Middle East within a sphere of US control. The military character of the American state has not only spelled disaster for the people who are on the receiving end of bombs and bullets and disorganization, but has also affected Americans at home by intensifying authoritarian mentality, leading to the emergence of a security state, in which freedoms and rights guaranteed by the US constitution have been routinely suppressed.

One important feature of this period has been dedicated US political, economic, and military support for the state of Israel. Prior to the mid-1970s, official financial aid to Israel was, for the most part, in the form of loans, which amounted to, at most, around half a billion dollars. From 1974 on, the US made large grants to Israel, , in addition to the loans, most in the form of military aid, ranging from two billion to more than four billion annually. Not including the money that flows into Israel from private groups, aid to Israel represents the largest item in the US foreign-aid budget.

Given the fact that Israel is the most powerful military force in the region, such a level of financial support makes little sense from a security standpoint. As Steve Zunes points out, one would expect that military aid to Israel “should have been highest during Israel’s early years, and would have declined as Israel grew stronger,” however “99 percent of all US aid to Israel took place after the June 1967 war, when Israel found itself more powerful than any combination of Arab armies” “The Strategic Functions of US Aid to Israel.” However, Zunes notes that there are hegemonic benefits to the US supporting Israel: a client state working to destabilize nationalist movements, an intelligence agency, an arms broker, and a consumer of US made weaponry. This last point is secured by the presence of a powerful Israel lobby in Washington. John Mearsheimer, Professor of Political Science at Chicago and Stephen Walt, Professor of International Affairs at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard argue that while “[o]ther special-interest groups have managed to skew foreign policy, …no lobby has managed to divert it as far from what the national interest would suggest, while simultaneously convincing Americans that US interests and those of the other country—in this case, Israel—are essentially identical,” than has the Israel Lobby (See “The Israel Lobby”, London Review of Books 28 [6], March 23, 2006). Israel uses the moneys it receives to colonize Palestine, a project that requires the construction of settlements and the violent suppression of the indigenous population. Much of that money stays in the United States, purchasing military hardware.

What is more, there is a dedicated group of US elites who believe Israel and the United States’ interests are inextricably bound together. One in particular has had a disproportionate impact on foreign policy towards the Middle East: Henry “Scoop” Jackson. Jackson, an influential Democratic Senator serving from 1941 to 1981, developed his understanding of foreign policy by carefully watching Israel’s conquest of Palestine. At the Conference on International Terrorism sponsored by the Jonathan Institute in 1979, Jackson articulated lessons learned by praising Israel’s suppression of Palestinian terrorists. He rejected the premise that the targets of terrorism should negotiate with terrorists. “To insist that free nations negotiate with terrorist organizations can only strengthen the latter and weaken the former.” He rejected the premise of Palestinian statehood. He said, “To crown with statehood a movement based on terrorism would devastate the moral authority that rightly lies behind the effort of free states everywhere to combat terrorism.”

His philosophy, known as “Jacksonian Zionism,” was at odds with the Democratic Party. Many Democrats — the “doves” — were arguing that peace was the path to regional stability. Conservative Democrats — the “hawks” — accused the doves of taking a “blame America first” approach, since it implied that terrorism was a reaction by oppressed people to Western imperialism. The dispute caused Jackson’s aides — among them Elliot Abrams, Douglas Feith, Richard Perle, and Paul Wolfowitz — to switch to the Republican Party, coming to staff the Reagan and Bush administrations. This is one key to understanding foreign policy planning from the 1980s onward: The chief architects of Bush’s Middle East policy, besides Cheney and Rumsfeld, were Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, and Douglas Feith, and several others who were disciples of Henry Scoop Jackson. They became known as the “neocons” (short for neoconservatives). They see Israeli interests as identical with US interests and several of them have in fact been advisors to the right-wing Likud Party of Israel.

Here are two examples that show how closely neoconservatives working in the US government are aligned with right politics in Israel. In 1996, while serving with the prominent Israeli think tank, The Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies (IASPS), Perle, along with Douglas Feith, the current Undersecretary of Defense for the United States, and David Wurmser, current Middle East and National Security Affairs advisor to Vice President Cheney, authored the report, A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm. They wrote the report for the right wing and Jewish restorationist Likud Party of Israel. The document advised then-prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, to walk away from the Oslo accord. In 1997, in A Strategy for Israel, Douglas Feith followed up on the report and argued that Israel should re-occupy the areas under the control of the Palestinian Authority (which they did). “The price in blood would be high,” he wrote, but such a move would be a necessary “detoxification” of the situation. This was, in Feith’s view, “the only way out of Oslo’s web.” In the report, Feith linked Israel’s rejection of the peace process to the neoconservatives’ obsession with the rule of Saddam Hussein and the Ba’ath regime. “Removing Saddam from power,” Feith wrote, is “an important Israeli strategic objective.” [For details, see my chapter, titled “War Hawks and the Ugly American: The Origins of Bush’s Central Asia and Middle East Policy,” in Bernd Hamm’s Devastating Society: The Neo-conservative Assault on Democracy and Justice London: Pluto Press, 2005, pp. 47-66. There is an Arabic-language version of this book published by All Prints, Beirut (News, as well as a German-language version Gesellschaft zerstören published by Homilius Verlag, Berlin.)

Assuming that a significant foreign policy direction in a democracy requires some degree of popular support, the facts of economic imperative and dedicated hard-line Zionists shaping and influencing US foreign policy are insufficient facts for understanding US policy in this period. Indeed, for much of the twentieth century, American conservatives, particularly religious conservatives, have held great antipathy towards the Jews. Moreover, conservative Republicans have traditionally been reluctant to support US intervention, democracy promotion, and national building.

Robert Herzstein records that “proper, prosperous mainstream Americans,” especially those “on the right” held extremist anti-Semitic sentiments (Professor of History at the University of South Carolina, records in his book Roosevelt and Hitler: Prelude to War (New York: Paragon House, 1989). A survey conducted by Fortune magazine in 1936 found that 500,000 persons reported attending at least one anti-Semitic rally the previous year. Anti-Semitism was particularly true in religious circles. In the traditional conservative Christian worldview, Jews are depicted as liberal puppet masters pulling the strings of communists, civil rights leaders, and feminists. These views were especially prevalent in the southern United States, where conservative Christians have historically been concentrated. Following WWII, open antipathy towards Jews shifted to widespread ambivalence towards Jews and Israel; nonetheless, there remained a deep anti-Semitism in American Christian culture.

Christian fundamentalism has not lessened in the years since. On the contrary. According to The New York Times in 2003, perhaps as much as 46 percent of Americans are evangelical or born-again Christians, and they are disproportionately Republican—72 percent of them voted for Republican candidates in 2004 (Nicholas Kristof, “God, Satan and the Media,” March 4, 2003). According to Gallup poll numbers taken in 2003, Bush’s popularity stood at 74% among born-again Christians. “The fact that this conservative and deeply religious president is a Republican is directly in line with the overall pattern of religious beliefs in American politics. Most scholars agree that there is a substantial relationship between strong religious faith, particularly within conservative, evangelical Protestant denominations, and identification with the Republican Party” (Frank Newport and Joseph Carroll, “Gallup Poll: Support for Bush Significantly Higher Among More Religious Americans,” March 5, 2003). Conservative Christians are vocal, committed, and organized. These cannot be the same fundamentalists who viewed Jews as evil only forty years earlier.

In the 1970s, as Christian conservatives were moving to take over American politics, political and religious elites launched a major effort to create widespread and uncritical support for Israel and Zionism (For an examination of a key aspect of this effort, see Norman Finkelstein’s The Holocaust Industry). This could happen if right-wing Christians and right-wing Jews were to see the preservation of Israel and the defeat of national aspirations of the Palestinians as shared interests. This common interest was fashioned into neo-fundamentalist Christianity. The Republican Party, the neo-conservative movement, and right-wing Jews, joined by influential conservative Christian leaders, fashioned an ideology that would secure the support of tens of millions of Americans for Western imperialism in the Middle East, serve the interests of capitalists seeking cheap fossil fuel to power the global economic system. This movement represented a historic shift from anti-Semitic fundamentalist Christian culture to a pro-Israel neo-fundamentalist Christian politics.

Christian neo-fundamentalism is a contemporary type of Christianity possessing a character of doctrinal militancy and aggressive missionary zeal. Neo-fundamentalists draw a sharp contrast between their faith and liberal Protestantism and Catholicism. Muslims are viewed as the “dangerous other” in this system, Islam representing an evil ideology.

There are five principles at the core of neo-fundamentalist Christianity. Rebirth involves a revelation in which a person accepts Jesus into their heart and turns himself completely over to the Holy Spirit. This act of becoming “born again” washes away that person’s sins. Sola scriptura — a rigid adherence to a literalist interpretation of the Bible. This is the view that the Bible is the sole source of religious authority. Missionarism — the practice of aggressive ministry and outreach to both Christians and non-Christians. The goal is to convert others to the Christian religion. Politicization — a commitment to pushing conservative Christian values into the larger cultural-political realm. This is what I have referred to as Christianism. Here definitions of “true Christian” are set forth. One who does not adhere to the definition is considered “unchristian.” Dispensationalism — this is a complex view, the relevant aspect of which, for our purposes here, is the focus on Jewish restorationism. Christian Zionists believe that the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and the return of Jews to the Holy Land, all set forth in prophecy (Revelations), put in motion the “end times,” in which God returns to claim his people for eternal existence in Heaven.

There are several well-known representatives of Christian Zionism, including Robert Grant, who founded Christian Voice in 1978; Jerry Falwell, who founded the Moral Majority in 1979; and Pat Robertson, who founded the Christian Coalition in 1988. There are others who are perhaps less well-known to people outside of America. As Bush was gearing up his presidential campaign, he made a pilgrimage to a gathering of right-wing Christian activists, organized as the Committee to Restore American Values, which was conducted by two dozen leading fundamentalists, and chaired by an apocalyptic evangelist Tim LaHaye. LaHaye presented Bush with a lengthy questionnaire on issues such as abortion, education, gun control, judicial appointments, religious freedom, and the Middle East. Hal Lindsey, who describes himself as an oracle, was an advisor to Ronald Reagan, who believed that “everything is in place for the battle of Armageddon and the Second Coming of Christ.” The Late Great Planet Earth, Lindsey’s most famous book, predicts the rebirth of Israel and war in the Middle East. “These and other signs, foreseen by prophets from Moses to Jesus, portend the coming of an antichrist…of a war that will bring humanity to the brink of destruction…and of incredible deliverance for a desperate, dying planet.” James Robison advocates a similar vision: “There’ll be no peace until Jesus comes. Any preaching of peace prior to this return is heresy; it’s against the word of God; it’s anti-Christ.”

Atheists should commit much effort to understanding the way the world appears to the Christian neo-fundamentalists and how this worldview moves the Christian to support US foreign policy in the Middle East. We must also show how state actors use Christian neo-fundamentalism to gain support for government policy. These intersect in the fact that many key state actors use faith to justify policy and believe in the tenets of Christian neo-fundamentalism. The proof is in the statements by the leaders themselves, and these quotes represent to many Americans I speak with the most frightening aspects of Christianism in the United States.

Reagan believed, as early as 1971, that “everything is in place for the battle of Armageddon and the Second Coming of Christ.” He left no doubt about his dedication to an apocalyptic view of history when he said, “In the 38th chapter of Ezekiel, it says that the land of Israel will come under attack by the armies of the ungodly nations and it says that Libya will be among them. Do you understand the significance of that? Libya has now gone communist, and that’s a sign that the day of Armageddon isn’t that far off…. Everything is falling into place…. Ezekiel tells us that Gog, the nation that will lead all of the other powers of darkness against Israel, will come out of the north…. Now that Russia has become communist and atheistic, now that Russia has set itself against God, now it fits the description of Gog perfectly.” He held these views into his presidency. In 1983, President Reagan told People magazine that never “has there ever been a time in which so many of the prophecies are coming together. There have been times in the past when people thought the end of the world was coming and so forth, but never anything like this” (reported in Holly Sklar, The Trilateral Commission and Elite Planning for World Management, South End Press, Boston, 1980).

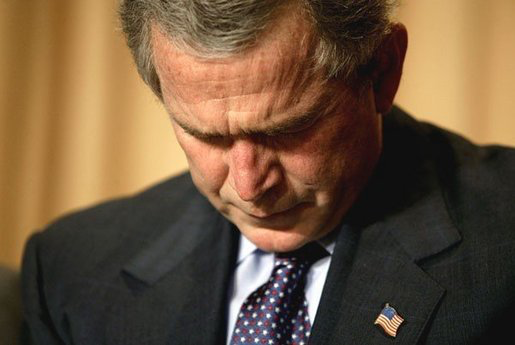

The current president, George W. Bush, follows Reagan in depth of religiosity, but adds to this the belief that his presidency is willed by God. As Governor of Texas, he told a friend, “God wants me to run for president” (Paul Harris, “Bush says God chose him to lead his nation”, Observer, November 2, 2003). A Time magazine article reports that Bush has “talked of being chosen by the grace of God.” (See “An Evolving Faith: Does the president believe he has a divine mandate?” Deborah Caldwell, BeliefNet.) According to Bush, this calling occurred during a 1999 sermon by Mark Craig, the preacher at Bush’s church in Dallas. Craig spoke of Moses’ reluctance to heed the calling of the Lord. In that sermon, Bush heard God calling him to become the President of the United States. One can hear the commitment to a Biblical view of history in Bush’s speeches. “We are not this story’s author, who fills time and eternity with his purpose. Yet his purpose is achieved in our duty…. This work continues. This story goes on. And an angel still rides in the whirlwind and directs this storm,” he said at his Inaugural Address in 2001. At the fifty-first National Prayer Breakfast, held February 2003 in Washington DC he said, “We can…be confident in the ways of Providence, even when they are far from our understanding. Events aren’t moved by blind change and chance. Behind all of life and all of history, there’s a dedication and purpose, set by the hand of a just and faithful God.” As reported in many mainstream press sources, Bush told both the former Palestinian foreign minister Nabil Shaath and former prime minister and now Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas: “I’m driven with a mission from God. God would tell me, ‘George, go and fight those terrorists in Afghanistan.’ And I did, and then God would tell me, ‘George go and end the tyranny in Iraq,’ and I did.”

One of Bush’s top military officials, General William Boykin, Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence, who has played key roles in several recent military operations, asserts that the war on terror is a fight against Satan. It is a conflict between a “Christian nation” and “radical Islamists,” Boykin claims. Islamists hate the United States “because we’re a Christian nation.” He proclaims that the US Army is “a Christian army.” He has publicly uttered such things as

“Ladies and gentleman, this is your enemy. It is the principalities of darkness. It is a demonic presence in that city that God revealed to me as the enemy.” “Now ask yourself: Why is this man in the White House? The majority of Americans did not vote for him. Why is he there? He’s in the White House because God put him there for a time such as this. God put him there to lead not only this nation but to lead the world in such a time as this.” “We in the army of God, in the house of God, kingdom of God, have been raised for such a time as this.”

(See “Whether God Speaks to Him or Not, Bush’s Religious Fanaticism has Shaped Our World,” The Independent (London), October 8, 2005, “The Army’s Three-Star Zealot,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 17, 2003, and “War on terrorism ‘clash against Satan’: Rumsfeld defends officer’s assertion of battle against the devil,” The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec), October 17, 2003. For more on Christianism in the military, see http://militaryreligiousfreedom.org/.)

Julian Borger, writing in The Guardian, provides a compelling analysis of the meaning of Bush’s delusions of grandeur: “While most people saw the extraordinary circumstances of the 2000 election as a fluke, Bush and his closest supporters saw it as yet another sign he was chosen to lead. Later, September 11 ‘revealed’ what he was there for.” The President said in the State of the Union address, “this call of history has come to the right country” (January 28, 2003). Members of Bush’s staff believe that God chose their boss to lead the nation through these times. After his speech to Congress on September 20, 2001, Bush received a phone call from speechwriter Mike Gerson, who said, “Mr. President, when I saw you on television, I thought—God wanted you there.” (Caldwell, The Times Union, Albany, NY, 2-16-03.) Tim Goeglein, deputy director of the White House public liaison, once remarked, “President Bush is God’s man at this hour.” (Joel Rosenberg, World Magazine, October 6, 2001.)

The depth of fundamentalism in the Bush administration is the subject of a book by one of Bush’s key speechwriters, David Frum, the man who coined the phrase “axis of evil.” According to his book, The Right Man, a work actually praising Bush, Frum, Bush, and others who worked on the notorious Axis of Evil speech, desired very much to create an enemy the equivalent of Reagan’s Evil Empire. According to Frum, during the weeks leading up to Bush’s 2002 State of the Union Address, Gerson came to Frum with this challenge: “Can you sum up in a sentence or two our best case for going after Iraq?” This was in late December 2001. Frum came up with “axis of hatred.” He felt that the phrase “described the ominous but ill-defined links between Iraq and terrorism.” Gerson replaced the word “hatred” with “evil” because the latter sounded more “theological.” Frum really liked the phrase. He says, “It was the sort of language President Bush used.” (Julian Borger, in The Guardian, discussed these matters with Frum in an article published January 28, 2003. In the interview, Frum “talks about the disconcerting grip evangelical Christianity has on the White House.”

Any explanation for public support for the United States’ interventions in the Middle East must account for the degree and character of religiosity in the United States. This includes Bush’s religious views. “It’s impossible to understand President Bush without acknowledging the centrality of his faith,” writes Kristof. As I wrote in a 2003 article, “Faith Matters: George Bush and Providence”, published by The Public Eye, Bush’s war efforts reflect a “messianic vision” in which his administration will “‘remake’ the Middle East.” Rutgers University history professor Jackson Lears, in a letter to The New York Times, “How a War became a Crusade” (March 11, 2003), suggests that this is why Bush can be so cavalier about war in Iraq will, because the president “denies the very existence of chance.” This follows from Bush’s belief that events in the world “aren’t moved by blind change and chance,” but rather are determined by “the hand of a just and faithful God.” Linking war with Iraq to an eschatological view of history intersects with the problem of ignorance of just war principles among evangelicals. Neither the President nor his supporters concern themselves with the justness of war, nor do they worry much about the consequences of war. Providence, according to Lears, “sanitizes the messy actualities of war and its aftermath. Like the strategists’ faith in smart bombs, faith in Providence frees one from having to consider the role of chance in armed conflict, the least predictable of human affairs. Between divine will and American know-how, we have everything under control.”

As I noted in my writings and speeches back before the war, one might think that the vast majority of Americans would find Bush’s extremist worldview disturbing. But no such majority has spoken up. Part of this has to do with overwhelming media support of this president, which has led the media to gloss over the President’s religious fundamentalism. This support, though waning somewhat with the catastrophe in Iraq, is still rather deep. The warmongering of major media outlets aligns them with the interests of the Bush Administration. I argued in 2003 that the media should not absorb all the blame since Bush’s major speeches have been nationally televised, unmediated by pundits, and still there is minimal concern over his apocalyptic rhetoric. However, the media could have spent the past several years discussing not only Bush’s religious fanaticism but also educating the public on why religious fanaticism is so detrimental to US objectives in the world—assuming those objectives are what our leaders say they are, namely peace, security, and justice.

Let me close with a word on the hypocrisy that inheres in the way religiosity and political extremism are represented by dominant voices in the United States. Americans are told that the problems in the Middle East originate in extremist and totalistic religious sentiment that is held by a majority of the Arab population. The story is that this sentiment, known as Islam, is inherently conservative and fundamentalist and, when faithfully adhered to, and politicized, is inconsistent with, and in fact a barrier to democracy and freedom—democracy of course understood as democratic capitalism and economic liberty (the rhetoric of “democracy promotion”). “Proof” of Islam’s alleged “irrationalism” is readily available to Americans in images and stories generated by our pervasive culture industry. Coverage of Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s call to his country’s universities to purge its ranks of liberals and secularists is a typical example. The mass media exploited this moment to paint the Iranian president as a dangerous enemy of democracy. More generally, Americans are subjected to a welter of stories allegedly documenting the anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism said to inhere in the Islamic thought. Americans are told that Muslims hate Americans and Israelis because Muslims hate freedom and progress, which, it is assumed in this rhetoric, Americans and Israelis embody.

The portrait of intense religiosity and irrationalism on the Arab side is designed to make Islam appear to stand in stark contrast to the secularism and rationalism inherent to Western political and cultural life, a perfectly reasonable context in which plurality and tolerance are said to prevail (hence the irony that religious conservatives simultaneously boast of and object to this progressive portrait of America). The West, we are reminded, long ago negotiated a separation of religious society and political society — what we call the wall of separation of church and state — and this arrangement prevents the fanaticism that allegedly prevails in the Middle East from taking hold in the West — unless outsiders bring it to the West (a fear that has led to considerable oppression of Arabs and Muslims in the United States). It is true that this arrangement was set down in the bill of rights attached to our founding document (the Constitution), which states unambiguously: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof….” But an arrangement only works if people keep at it. And in the United States the wall is in great need of repair.

Note: Max Blumenthal was present at the Hagee conference and produced this documentary. Rapture Ready: The Christians United for Israel Tour.