Steven Pearlstein, writing in The Washington Post, argues,

It is more than a bit disingenuous for liberals to push for worthwhile programs like food stamps, housing vouchers, child tax credits and the earned income tax credit – and then to constantly cite official income and poverty statistics that do not include the impact of food stamps, housing vouchers, child tax credits and the earned income tax credit.

Why is that (more than a bit) disingenuous? For any maximally-objective grasp of things, we need to develop an honest empirical profile of the problem without the effects of the solution confounding it. Imagine if a doctor examined a patient whose symptoms were masked by another doctor’s previous intervention. The present doctor would quite likely miss the underlying condition affecting the patient. There is nothing at all disingenuous about wanting to see the patient’s medical records before drawing conclusions about the patient’s case. Indeed, that must be the approach the doctor takes.

This is not to say that having an after-intervention accounting of things isn’t useful. How else would one know if the intervention is working? More importantly, how else would one know if a different and better intervention was needed? As if we are ignorant of such things, Pearlstein believes he has to remind us that there is an after-intervention accounting:

[E]ach spring the Census Bureau gets around to computing an alternative after-tax measure of disposable income that includes these various tax and transfer programs, while also making adjustments in the official poverty line to reflect the economic realities of different household sizes…. In 2005, for example, they dropped the poverty rate from 12.6 percent to 10.3 percent, with the biggest improvement coming in a four-percentage-point reduction in child poverty.

In response to this account, Pearlstein notes the obvious, that “these revisions help put the lie to the right-wing conceit that government tax and transfer policies only make poverty worse.” But then he misses the most important fact – that even after adding in the benefits of government programs, one out of every ten Americans still lives in poverty. Moreover, for minorities that ratio is a lot more dramatic. (Frankly, to have one chronically poor person in the wealthiest nation on earth is a scandal, but more on that in a moment.)

Instead, Pearlstein comments,

Conservatives are left to fall back on the argument that government handouts and social insurance programs, while appearing to lift some out of poverty, have created a permanent underclass by discouraging work and thrift and fostering a culture of dependence.

Don’t expect Pearlstein to go on to blast the classist-racist-sexist “culture of poverty” thesis. Instead, he brings in Charles Karelis’ arguments from his new book The Persistence of Poverty. Karelis is the philosopher at George Washington University who argues that people are poor because they don’t have enough money. Before you scoff at Karelis’ tautology (I had a social problems professor who made the same observation), Pearlstein elaborates Karelis’ argument:

The reason the poor are poor is that they are more likely to not finish school, not work, not save, and get hooked on drugs and alcohol and run afoul of the law. Liberals tend to blame it on history (slavery) or lack of opportunity (poor schools, discrimination), while conservatives blame government (welfare) and personal failings (lack of discipline), but both sides agree that these behaviors are so contrary to self-interest that they must be irrational.

The only historical reason liberals give for poverty is slavery? That will come as a surprise to anybody who reads liberal scholarship on the subject. What about the oft-noted facts of the ghetto and Jim Crow segregation, de facto and de jure forces that have created a system of racial separation that continues to divide blacks and whites not only in housing, but also in occupation, education, and dozens of other things. Discrimination is rooted in the continuing objective system (or structure, if you like) of apartheid. A New Liberal, armed with the weapons of social science, should neither blame poverty only on slavery nor know discrimination only as an interpersonal phenomenon disconnected from an underlying system of racial separation. (As a Marxist, I don’t consider myself a liberal, but one thing clearly separating liberals from conservatives is a superior grasp of the methods and findings of sound social science.)

The conservative argument that poverty results from lack of discipline ignores the reality that our wealthiest citizens are the worst when it comes to discipline. Let us be blunt about the truth here: the wealthiest among us do little or no productive work. They don’t even mow their own lawns. I know they want the rest of us to believe they are the new Apostles of Christ, but in truth, their lives are spent in leisure, where their only concern for time is making sure they meet friends and business associates for golf games or have their weekly pedicure performed by their favorite salon employee. Wealthy parents allow their children free rein over their own lives protected within an exclusive communal cocoon. The male children of wealthy families are especially undisciplined (and frequently obnoxious to boot).

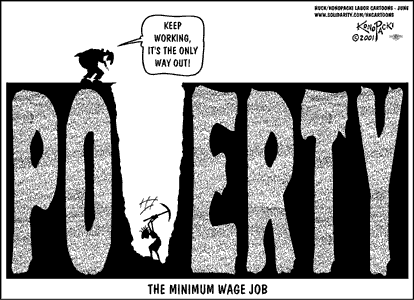

Contrast this existence with the lives of the working poor, who exhibit an extremely disciplined manner in making sure not only that they get to work on time every day and every night at their two or more part-time jobs, but that their children learn to unquestioningly respect authority (training to their children’s detriment, in my opinion, since respect for authority makes it harder to develop the consciousness sufficient for rebellion and revolution, which is sorely needed). Indeed, the strictest disciplinarians in American society are working people, especially the working poor.

Ultimately, then, several assumptions Pearlstein and Karelis operate with are wrong. First, in contrast to the wealthy, the poor do work. They work hard. It is expensive being poor, as Ehrenreich famously observed, and you have to work all the time to be able to support that lifestyle. To say the poor are poor because they don’t work is to exhibit a profound ignorance of the reality of poverty. Second, contrary to assumptions in Karelis’ argument, the poor are no more likely to drink and drug than are the wealthy. The difference is that the wealthy can hide their drinking and drugging within gated communities. And they can afford private treatment when their drinking and drugging get out of hand. Third, running afoul of the law has more to do with who breaks the law than it does about the essence of the behaviors to which the law is applied. The wealthy commit all manner of illegal, immoral, unethical, and socially dangerous acts, yet they are relatively immune from the sanctions that control or should control these acts. There’s a reason why our prisons are overflowing with poor people and not rich people, and it has very little to do with actual criminality. Fourth, if not working, drinking and drugging, and breaking the law cause poverty, then the wealthiest among us would be the poorest among us. Obviously that is an absurdity, hence the absurdity of Karelis’ argument.

There is an important and relevant truth in all this: wealth is passed on, either directly in inheritance or indirectly through the good fortune of being a child born to well-off parents. Indeed, this is the justification for passing wealth along! But the same is true for the poor – only here, the disadvantages accumulate. Since, there’s no such thing as parental selection, it ridiculous to blame the poor for poverty (something akin to blaming a corpse for murder). The structure of American society is such that it accumulates advantages at one end while accumulating disadvantages at the other. That is the fundamental character and operation of social class under capitalism. Without massive government intervention (such as we see in Scandinavia counties) or a socialist revolution (which is long overdue), nothing can be done about this.

Oblivious to the facts of the matter, Pearlstein opines,

After all, the reason we study, work, save and generally behave ourselves is that these behaviors allow us to earn more money, and more money will improve our lives. And, by logic, that must be particularly true of the poor, for whom each extra dollar to be earned or saved for a rainy day is surely more valuable than it is for, say, Bill Gates.

Yet, Pearlstein seems to understand something. After noting that the extension of logic in the previous paragraph is problematic, he writes,

On the other hand, maybe the point at which people are most willing to work hard, save and play by the rules isn’t when they are very poor, or very rich, but in the neighborhoods on either side of the point you might call economic sufficiency – a motivational sweet spot that, in statistical terms, might be defined as between 50 percent ($24,000) and 200 percent ($96,000) of median household income. And if that is so, then maybe the best way to break the cycle of poverty is to raise the hopes and expectations of the poor by putting them closer to the goal line.

Now, if he could only connect this observation to the reality he misses about the dynamic of capitalism, then he would understand that poverty can only be eliminated by getting rid of the wealthy (and I don’t mean persons but the station), since it is the lazy existence of the rich that forces so many millions of hard-working people into the hellish existence of poverty (where they are not only the victims of discrimination, but also of prejudice and shame, as well). Because a few have so much, the many have very little. Thus the conclusion Pearlstein reaches, that there is “a solid economic argument to replace the old moral ones for spending more money on programs like food stamps, subsidized child care and the earned income tax credit,” falls far short of a real and permanent solution. (Of course, generous social welfare programs are the least we can do as a civilized society.)

While liberals are mostly correct but insufficiently radical in all this, conservatives are completely wrong. As Pearlstein himself puts it, “after a decade of welfare reform, budget cuts and calls for individual responsibility, poverty is still very much with us.” The conservative solution to poverty is either to blame the poor for their situation – blame the corpse for murder – or to simply remind us that Jesus told us, “The poor will always be among us.” Just as they put the market beyond politics, they locate the source of poverty in theology, all of it out of the hands of “the haves.” How convenient.

Conservatives believe that poverty is explained by personal inadequacies, such as stupidity, bad values, and laziness. They believe that relief should be a gift of charity and that there should be conditions upon receiving it, such as performing menial labor. Aid should only be temporary, they say, and seeking it should carry stigma. Poor people should find public assistance an unpleasant experience so that receiving welfare is itself a deterrence to seeking it. Aid given to poor people should be minimal; the poor would prefer to receive generous aid rather than work so any assistance should always be much less than what they could get if they worked for the lowest possible wage. Fear of hunger and discomfort must exist to compel the poor to work. Individuals make their own decisions and society should not protect persons from the negative consequences of their actions.

Such beliefs are bizarre in light of the way the world actually works. At the individual level, poverty is almost always caused by factors beyond an individual’s control. This is because, at the structural level, poverty is the result of social stratification. Any society that is divided by class is necessarily a society in which the social product is unequally distributed; otherwise, there would be no social classes, there would be no inequality, there would be no poverty. In class systems, some get more for doing less, while others get less for doing more. This is the source of wealth and poverty in society. While some poor people may find their way out of poverty, there will always be poor people in a class society. Since you cannot blame the poor persons for the structure of the societal order, seeing how they haven’t the poor to determine that order, the conservative argument is irrational.

But it’s more than irrational. It’s hateful. Loving and compassionate human beings care about their brothers and sisters. Persons with a normal moral capacity believe that the poor are entitled to aid, since it is not their fault that they are poor. Ethical persons don’t blame victims. If all persons were free to produce for themselves, they would be no need for aid at all. Having people perform menial tasks with no productive or creative value is degrading; as a rule, human beings should never be forced to routinely perform work they do not find fulfilling. Because human beings realize themselves through productive work, most individuals prefer rewarding creative endeavor over receiving aid. The problem is that not everybody is allowed to pursue creative endeavors sufficient for the production of an adequate social provision for themselves. This is because there are some who get a lot for doing very little. They are called capitalists.