Note (November 7, 2023): I was asked a provocative question this morning referencing this essay asking me to consider the question of why child pornography should be criminal and how does my response bear on the arguments presented here. “Isn’t it crime scene photography?” was the question.

When does a photograph, film, or video documenting a crime scene constitute a criminal offense itself. As a criminologist, I have seen quite a bit of crime scene photography, filmography, and videography. I wrote an essay about the matter inspired by James Allen’s 1999 Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America for The Journal of Black Studies several years ago. I compared the atrocities memorialized in those photographs to those of the Holocaust. While the photographs document crimes, collecting, distributing, and distributing them is not criminal. Indeed, it is of great importance that people have access to this material in order to grasp the significance of these crimes.

Memorializing the sexual exploitation of a child, which is a criminal act, since children can’t consent to such acts, recorded in the various media in which they fixed, is a criminal act in the same way that secretly recording women in a dressing room or the rape of a woman for personal or commercial purposes are or should be criminal offenses. To be sure, there is pornography that simulates these things; but if the women in the video consented to the acts depicted, they are not the victim of a crime. Presently, consensual sex acts conducted for the purposes of commercial pornography is legal in the United States. However, surveillance of women or raping them without their consent is not. The fruits of these crimes are also crime.

However, to relate this back to the essay, AI images are not of actual people. They are analogous to cartoons, drawings, paintings, etc., depicting ideas originating in the imagination of a man’s mind. That’s why I noted the work or R. Crumb. I won’t share his cartoons here, but you can find his work online. See, for example, his 1970 comic “Mr. Natural in ‘On the Bum Again’,” collected in Zap-Masters (2009). The story concerns a character called “Big Baby.” I won’t describe the content, but it’s explicitly pedophilic. The question one must ask in determining whether it’s criminal is whether an actual child was victimized in the production of the comic. If the answer no, then criminalizing the comic beyond that is thought crime.

In a 2017 issue of The British Journal of Criminology, in the article, Why Do Offenders Tape Their Crimes? Sveinung Sandberg and Thomas Ugelvik conclude: “New technologies are changing the way crimes are committed and the harmful consequences they have. Researchers, legislators and the victim support system need to take these changes seriously. For researchers, these developments call for an integration of insights taken from cultural, visual and narrative criminology. For legislators and the legal system, the additional harm following the recording and distribution of images of crime should be taken into account when legislating and sentencing in cases involving the use of cameras.”

* * *

The institution of thought crime sneaks up on folks. You have to know what to look for. The Internet Watch Foundation (IWF), a British-based child safeguarding charity specializing in detecting, reporting, and minimizing child pornography, published a story a few days ago: “‘Worst nightmares’ come true as predators are able to make thousands of new AI images of real child victims.” “International collaboration vital as ‘real world’ abuses of AI escalate,” the subtitle goes. You might remember the IWF from its controversy years ago over the original album cover for the Scorpions’ Virgin Killer, which the IWF blacklisted. They dropped their blacklisting, but it was a sign of things to come. (One of many signs. Look them up.)

Those who read my blog know that I take a backseat to no one when it comes to child safeguarding. I’ve punished articles on this topic in the Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma and Sage’s Encyclopedia of Social Deviance, as well as several posts here at Freedom and Reason (Seeing and Admitting Grooming; Luring Children to the Edge: The Panic Over Lost Opportunities; What is Grooming?). However, if heeded, the implications of the demands of the IWF, threaten fundamental freedoms of conscience, expression, and speech. A sober examination of the problem of virtual child pornography is therefore in order.

For those who conflate the defense of free thought with being guilty of the thoughts authoritarians seek to censor, fuck off. I can’t imagine what would make a person sexually interested in children. I have the same thought about people who fantasize about rape and murder. I can’t emphasize. I can work with statistical patterns in an attempt to predict outcomes, but these are abstractions—and there’s the problem of false positives. What I care about is (a) prosecuting those individuals who actually harm concrete individuals in provable cases in courts of law, and (b) preventing the state from criminalizing art, expression, speech, and thought. Why (b) is important is because I don’t want to live in an Orwellian nightmare. Do you?

The IWF purports to reveal the disturbing extent of AI-generated child sexual abuse imagery, having reportedly uncovered thousands of such images, some featuring (fictional) children under two years old. They cite their own work: How AI is being abused to create child sexual abuse imagery. “In 2023, the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) has been investigating its first reports of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) generated by artificial intelligence (AI).” Cue the moral panic.

CSAM stands for child sexual abuse material. Several organizations, most prominently RAINN (Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network), have stopped using the term “child pornography” in favor of the acronym CSAM because “it’s more accurate to call it what it is: evidence of child sexual abuse” (see “What is Child Sexual Abuse Material”). “While some of the pornography online depicts adults who have consented to be filmed, that’s never the case when the images depict children. Just as kids can’t legally consent to sex, they can’t consent to having images of their abuse recorded and distributed. Every explicit photo or video of a kid is actually evidence that the child has been a victim of sexual abuse.”

I emphasized that last sentence because this is what makes such images illegal: it is the memorialization of actual child victimization. United States law and precedent agree: “It is important to distinguish child pornography from the more conventional understanding of the term pornography. Child pornography is a form of child sexual exploitation, and each image graphically memorializes the sexual abuse of that child. Each child involved in the production of an image is a victim of sexual abuse.” (See Citizen’s Guide To U.S. Federal Law On Child Pornography.)

IWF warns the reader about the dark world of text-to-image technology. “In short, you type in what you want to see in online generators and the software generates the image. The technology is fast and accurate—images usually fit the text description very well. Many images can be generated at once—you are only really limited by the speed of your computer. You can then pick out your favorites; edit them; direct the technology to output exactly what you want.” The AI systems that generate virtual child porn work the same way as AI systems generating virtual adult porn. That’s because they’re the same systems. After considerable research, here’s what I understand about the process.

AI image generators work by using neural networks, particularly a class of learning models known as generative adversarial networks (GANs) or variational auto-encoders (VAEs), designed to produce images that resemble a given dataset. The key word here is resemble. The first step in the process is to gather a large dataset of images. These images are used to train the AI image generator. The quality of the generated images largely depends on the diversity and quality of the training data (as well as hyper-parameters and post-processing, but I won’t get into all that); neural networks are designed with specific architectures for image generation.

GANs consists of two neural networks: a generator and a discriminator. The generator takes random noise as input and generates images. The discriminator is trained to distinguish between real and generated images. These networks are trained simultaneously in a competitive manner. The generator’s goal is to create images that are indistinguishable from real ones. The discriminator’ s goal is to become better at telling real from generated images. VAEs consist of an encoder and a decoder. The encoder maps input images to a lower-dimensional space, i.e., latent space, and generates a probability distribution. The decoder takes samples from this distribution and reconstructs images from them. VAEs are trained to generate images that match the training data distribution.

During the training process, the generator learns to produce images that fool the discriminator (in the case of GANs) or reconstruct images faithfully (in the case of VAEs). The discriminator or encoder simultaneously improves its ability to distinguish between real and generated images or map input data to the latent space. GANs use a loss function that encourages the generator to produce images that the discriminator can’t distinguish from real ones. VAEs use a loss function that encourages the latent space to be structured in a way that makes it suitable for image generation. After training, the generator or decoder can take random noise or other inputs and produce images. The quality of the generated images improves as the training process progresses. AI systems are always learning.

IWF claims that the AI-generated images are made up of real images of children. But this misunderstands the process. The images generated by AI models are not copies of the source images that are used for training. Instead, these AI systems create synthetic images that are inspired by the patterns and features present in the training data. The generated images are not replicas of any specific source image but rather representations of what the model has learned about the general characteristics and structures of the training data. Put simply, the AI model learns statistical patterns and relationships from the training images and then uses this knowledge to generate entirely new images that may resemble the characteristics, content, and style of the training data. So, while the generated images may share similarities with the source images (e.g., they depict faces, poses, objects, or scenes), they are not copies or duplicates of any specific photograph; they are novel creations produced by the AI model.

In the case of images of children in sexually provocative poses or children involved in sexual activity, AI models never need to see actual photographs of children in sexual activities or situations. They have a universe of adults in sexualized scenarios, as well as a universe of children involved in various activities, to draw from. From its learning, systems re able to synthesize from these data entirely novel images that look photorealistic. The process works in much the same way that a human artist relies on his knowledge of the world to depict children in sexually provocative poses or involved in sexual activity. While we may find his work reprehensible, and would never attempt to draw such images ourselves, it is nonetheless the case that no child is sexually exploited in the process. The great cartoonist and graphic illustrator R. Crumb drew cartoons and illustrations (some photorealistic) that many observers find repulsive; however, they are just that: cartoons and illustrations. His brain generated those images from a universe of data downloaded in much the same way as an AI system does.

Should the generation and accumulation of these images be criminalized? That’s like asking whether R. Crumb is a criminal and his art contraband. Maybe you think so. I don’t. Moreover, the reaction risks assuming that all depictions of naked children are a priori instances of child sexual abuse. You might recall that Facebook and other web sites censored the cover art of Led Zeppelin’s album Houses of the Holy because it featured singer Robert Plant’s children naked on the cover. I have no doubt that there are individuals who find this album cover sexually arousing. Most others, however, find it a beautiful work of art. Whether it’s pornographic or not reflects the mind of the individual. There is nothing inherent in an image of a naked child that’s pornographic.

It is therefore rather beside the point—at least it should be—that the IWF indicates that the majority of AI-generated child sexual abuse images, as assessed by IWF analysts, now possess a level of realism that qualifies them as genuine images under UK law. The most convincing imagery is so lifelike, they claim, that even trained analysts struggle to differentiate it from actual photographs. Moreover, they warn, the use of text-to-image technology is expected to advance further, creating additional challenges for the IWF and law enforcement agencies. But this obscures the actual problem, which is the sexual exploitation of a really-existing child in the production of the image or video in question. If no actual child is depicted in the photograph, the question of whether the child was sexually exploited cannot follow, as no crime could have possibly taken place.

There is an asterisk associated with the second paragraph of the initial article cited above indicating an endnote. When we go to the endnote we find the following “AI CSAM is criminal—actionable under the same laws as real CSAM.” The laws identified are these: “The Protection of Children Act 1978 (as amended by the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994). This law criminalizes the taking, distribution and possession of an ‘indecent photograph or pseudo-photograph of a child.’” And: “The Coroners and Justice Act 2009. This law criminalizes the possession of ‘a prohibited image of a child.’ These are non-photographic—generally cartoons, drawings, animations or similar. AI CSAM is criminal—actionable under the same laws as real CSAM.”

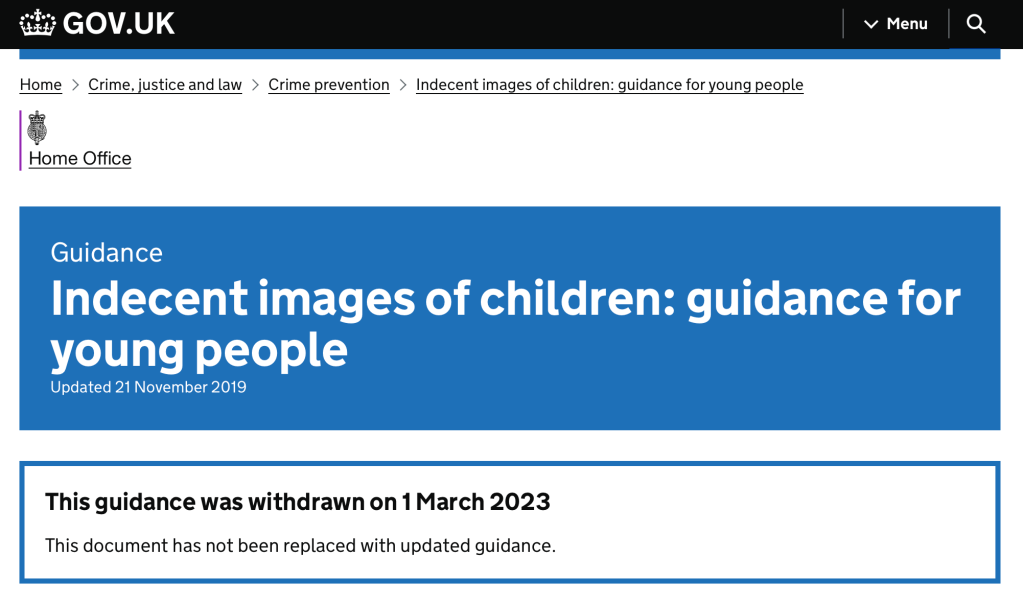

In guidance updated on November 21, 2019, titled “Indecent images of children: guidance for young people,” from the Home Office of the United Kingdom, referenced by IWF, while it does consider illegal “[t]aking, making, sharing and possessing indecent images and pseudo-photographs of people under 18,” that guidance was withdrawn on March 1, 2023. It is however, still instructive. Crucially, the withdrawn document defines a “pseudo-photograph” as “an image made by computer-graphics or otherwise which appears to be a photograph.” What counts as a pseudo-photograph? Photos, videos, tracings, and derivatives of a photograph, i.e., data that can be converted into a photograph. Moreover, while admitting that “‘indecent’ is not defined in legislation,” it “can include penetrative and non-penetrative sexual activity.” It defines “making” broadly as including opening, accessing, downloading, and storing pseudo-photographs.

The withdrawn document announces that it worked with IWF to ensure every one knows the law and understand that “looking at sexual images or videos of under 18s is illegal, even if you thought they looked older” and that “these are images of real children and young people, and viewing them causes further harm.” But, in the case of pseudo-photographs generated by AI, these are not images of real children. If we return to the definition of CSAM, what lies at the heart of the issue are images that represent evidence of child sexual abuse. In the case of either human-imagined or AI-generated images, there are no sexually exploited children. There are only representations of sexually exploited children, in this case, children who do not exist. These are simulations, simulacra, and while the desire to make and consume them may offend our sensibilities, no crime has occurred except a thought crime, and at the end of that road lies totalitarianism.

People living in the UK beware. UK law does conflate images depicting child sexual abuse with images of child sexual abuse. In its guidance on Indecent and Prohibited Images of Children: “In deciding whether the image before you is a photograph/pseudo-photograph or a prohibited image apply the following test: If the image was printed would it look like a photograph (or a pseudo-photograph)? If it would then it should be prosecuted as such. For example, some high quality computer generated indecent images may be able to pass as photographs and should be prosecuted as such. The CPS has had successful prosecutions of computer-generated images as pseudo-photographs.” This is why IWF is concerned about the realistic nature of AI art.

Things are a bit different in America. Under United States law, which also prohibits CSAM, this does not include virtual child pornography or even all of what many would regard as child pornography. “Visual depictions include photographs, videos, digital or computer generated images indistinguishable from an actual minor, and images created, adapted, or modified, but appear to depict an identifiable, actual minor.” Note the emphasis on there being an actual minor involved. The meaning here is a little fuzzy. However, the Supreme Court clarified things in 2002.

In 1996, the ban on CSAM included sexually explicit material that “conveys the impression” that a child was involved in its creation, even if none was actually used. The Court ruled the “virtual pornography” law violated free speech rights. Justice Anthony Kennedy led the court majority, finding two provisions of the 1996 Child Pornography Prevention Act overly broad and unconstitutional. “The First Amendment requires a more precise restriction,” he wrote. Justices John Paul Stevens, David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer joined him. Justice Kennedy asserted in his opinion that virtual child pornography was not directly related to child sexual abuse. Justice Clarence Thomas joined the majority (writing a separate opinion).

I find it despicable that a person would find children sexually arousing. I am not offended by much, but this is one of those things that shocks the conscience. But in reality, no child is sexually exploited by an individual who does not act to exploit that child. To give the state the power to punish people for their thoughts is to give up man’s most fundamental freedom: the freedom to think what he will. Ask yourself, who will be the ultimate arbiter of what shall be considered criminal thoughts? The state? Don’t make a whip for your own back. States are not to be trusted.

Imagine if one day the United Kingdom falls to Islam (it could happen). Folks there will rue the day they gave the state power over their thoughts. Unfortunately, the British have no First Amendment—and they have given the state too much power over their thoughts already. Keep in mind that they’ve already moved to make frank acknowledgment of reality in the case of gender a hate crime. Conflating art, expression, speech, and thought with actual harm caused to actual people reveals the mind of the authority. And while a person may be free to conflate these things, freedom demands that the state must not take up his conflation. Indeed, such a man is free to think this way because he lives in a democratic society that protects the right of individuals to think freely, whatever the content of those thoughts.