“Mankind, which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic.” —Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936)

“[P]hilosophically, the progressive movement at the turn of the 20th century had roots in German philosophy (Hegel and Nietzsche were big favorites) and German public administration (Woodrow Wilson’s open reverence for Bismarck was typical among progressives). To simplify, progressive intellectuals were passionate advocates of rule by disinterested experts led by a strong unifying leader. They were in favor of using the state to mold social institutions in the interests of the collective. They thought that individualism and the Constitution were both outmoded.” —Charles Murray, “The Trouble Isn’t Liberals. It’s Progressives” (2014)

I begin this essay with a voice of moderation, Christopher Caldwell, who a few months ago penned an op-ed for The New York Times, “Americans Are Getting Too Used to This Form of Rule.” I was only recently made aware of the op-ed. It is a useful discussing of the emergence of administrative rule and its justification using the principle of emergency rule.

To convey the gravity of the matter, I remind readers that emergency rule comes in various forms. A state of emergency is a legal declaration by a government that grants exceptional powers to authorities in times of crisis. It typically involves the temporary suspension of certain rights and freedoms, allowing the government to take extraordinary measures to address the emergency situation. Emergency powers refers to the additional authorities and discretionary powers granted to the executive branch during a crisis. These powers may allow the government to bypass normal legislative procedures, enact regulations swiftly, and take necessary actions to address the emergency situation.

At the severe end, martial law refers to the imposition of direct military control over civilian functions and the suspension of civil law during a crisis. It involves the temporary transfer of authority from civilian government to military forces, which take charge of maintaining public order and security. The term “extraordinary measures” encompasses various actions taken during an emergency that deviate from normal governance procedures. These measures can include the suspension of constitutional rights, expanded surveillance powers, curfews, restrictions on movement, and increased government control over essential services. The less frequently used term “state of siege” is often used to describe a situation where a government heavily restricts civil liberties and deploys security forces to maintain order and combat threats. It typically involves the imposition of curfews, restrictions on public gatherings, and heightened security measures.

Readers will recognize that many of the rules imposed during the coronavirus pandemic—expanded surveillance powers, lockdowns and other restrictions on movement, increased government control over essential services—lay along the severe end of emergency rule (see Biden’s Biofascist Regime; Eugenics 2.0; Why Masks and the Sacred Word are the Panics du Jour).

Caldwell ticks off examples of administrative fiat via emergency powers. There is Bush’s declaration of a terrorist emergency in 2001, where his administration resorted to questionable shortcuts in various policy areas, such as the interrogation of criminal suspects and economic management. In response to the 2008 financial crisis, Obama took unilateral actions without the involvement of Congress. Later, in 2012, he protected immigrant children from deportation, and in 2013, he made adjustments to the Affordable Care Act. Since 2020, the Covid pandemic has further complicated matters, leading to a convoluted and undemocratic chain of accountability. Donald Trump declared a national emergency, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention even imposed an eviction moratorium, all without the input of Congress.

Caldwell brings us up to the present moment with respect to student loans, which the Supreme Court ruled on last week. The Biden administration did not view their actions as lawless improvisation, believing that Bush’s Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act of 2003, commonly known as the HEROES Act, provides a legal basis for the forgiveness of these loans. To be sure, the law allows the secretary of education to “waive or modify” student loan provisions during a national emergency; but, as Caldwell points out, “claiming the vast authority Mr. Biden does is really a stretch.” Caldwell explains that “the HEROES Act was to make sure soldiers didn’t get their school finances tangled up in red tape while fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq.” The Supreme Court corrected Biden’s obvious overreach and bid for the young American vote.

Caldwell is sympathetic to the desire for executive action. There are understandable reasons why the head of the executive branch, frustrated with congressional limitations, might exploit an emergency situation to exert authority. Surprisingly, even Congress, the branch of government whose powers are being usurped with such actions, has reasons to collude in emergency rule. For example, student loan relief is a contentious issue for politicians to navigate. Neglecting the plight of millions burdened by debt could cost them votes, while providing assistance may alienate older voters who feel they have already paid their dues.

Moreover, the identity of the students whose debts are being forgiven is crucial, Caldwell usefully notes. If they are newly qualified nurses who will alleviate pressure in emergency rooms, the nation may applaud. However, if they are privileged individuals with costly degrees in obscure subjects, such as postcolonial theory, the idea of federal aid to higher education may lose favor. Student loans become an issue where politicians can easily misinterpret public sentiment, potentially endangering their electoral prospects. Some members of Congress might even prefer having their authority usurped by the president.

However, Caldwell is right when he argues that, while a degree of executive discretion is necessary in a democracy, emergency rule cannot become a permanent system, especially in a deeply divided society like ours. And this is how we need to understand the Supreme Court’s decision in this matter. The concern with the current case before the court lies not in the Biden administration’s policy or ideology, but rather in the governance system that has emerged around emergency powers since the September 11 attacks. I argue well before then, but whenever it starts, the threat to democracy is great. Indeed, as I have argued in previous essays on this blog, the Republic may already be over. In light of this, Caldwell’s critique is subdued.

In 2007, author-activist Naomi Klein coined the term “disaster capitalism” to describe how corporations exploit natural disasters and wars to reap excessive profits. While her observation was sharp, Caldwell grants, it is important to note that the system she depicted is not exclusively aligned with free-market ideologies. There is also a phenomenon known as disaster progressivism, which leverages moments of shock or fear to enforce lasting changes that may not otherwise be accepted by the public. Caldwell is on to something here for sure. Shortly after Obama’s election in November 2008, Caldwell recalls, his incoming chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, said, “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste.”

Caldwell is correct that Biden’s loan forgiveness plan aligns with this approach to policymaking. “Whatever you call it,” he writes, “it’s not democracy but a democratic malfunction worthy of the court’s close attention.” The Supreme Court took a look at it this term and, on June 30, the Court rejected the plan, saying that the president had overstepped his authority.

However, the matter is worse than this or that president overstepping his authority. Much worse. It will take more than rulings handed down from our liberal Supreme Court to fix the problem. It will require more than a president who will deconstruct the administrative state—although at a minimum we must vote for either a Kennedy or a Trump to take the level of contradiction to a higher plane. But, ultimately, it will take marginalizing the misanthropic spirit that has colonized the Lebenswelt of a large proportion of the western population and build in its face a mass-based populist movement to reclaim the American Creed.

You may recall the Breitbart Doctrine, named after conservative thinker Andrew Breitbart, who asserted that “politics is downstream from culture,” that to change politics one must first change culture. Beitbart’s war was with what he and others in the conservative movement have called “cultural Marxism.” Breitbart and the media outlet that bears his name, Breitbart News, frequently dropped the term, employing it to critique what they perceived as a left-wing agenda within academia, media, and popular culture.

In the Breitbart Weltanschauung, cultural Marxism refers to an alleged Marxist influence on society that has shifted the focus from economic class struggle to cultural and identity issues. The critique holds that cultural Marxists, or neo-Marxists, seek to undermine traditional institutions, norms, and values, promoting ideas and practices such as multiculturalism, political correctness, and social justice, i.e., woke progressivism. Breitbart News and other conservative outlets frame these ideas as threats to conservative values and as a means for left-wing ideologies to infiltrate and shape cultural institutions.

It has been argued that the concept of cultural Marxism as discussed by Breitbart and other conservative commentators is has its origins in far-right conspiracy theories. I discuss that claim in my essay Cultural Marxism: Real Thing or Far-Right Antisemitic Conspiracy Theory? I contend that the claim that woke progressivism represents a form of Marxism is a misrepresentation of Marxist theory, but that the critique has merit when we adjust terms.

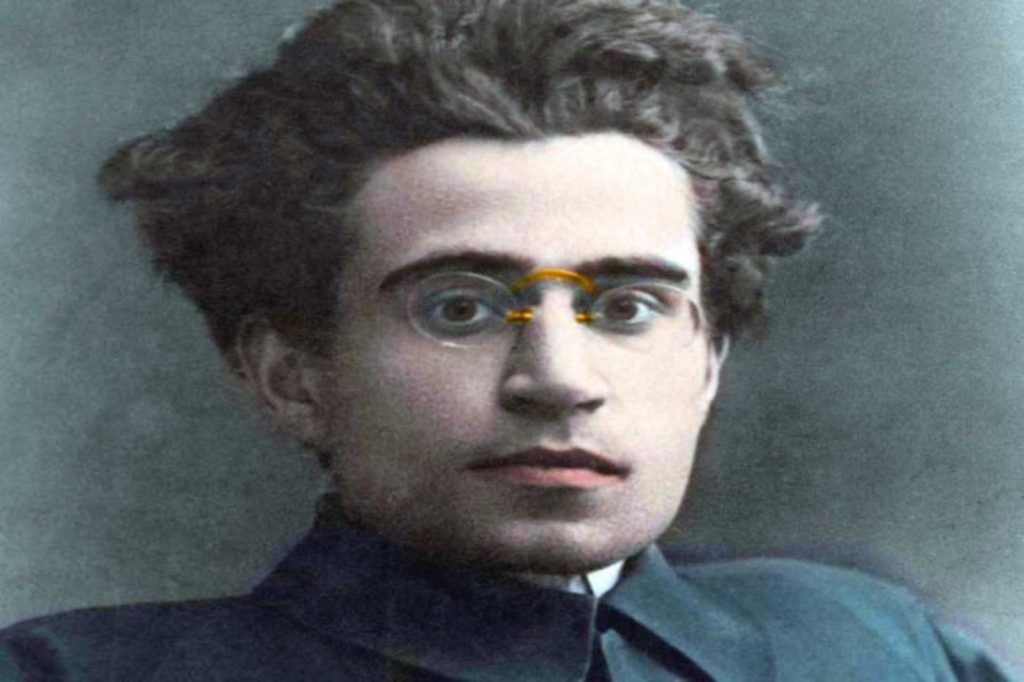

Some will recall that Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist philosopher and politician who languished in Mussolini’s prison, did express similar ideas regarding the relationship between politics and culture. Indeed, he did. Gramsci argued that cultural hegemony, or the dominance of a particular set of beliefs, norms, and values, plays a crucial role in shaping and maintaining political power. Gramsci believed that the ruling class maintains its dominance not only through economic and political control but also by commanding and shaping the cultural narratives and institutions that define society. He argued that the ruling class uses cultural institutions such as education, media, and religion to promote its own worldview and values, thereby creating a “common sense,” or “social logic” that serves its interests.

According to Gramsci, political power is ultimately derived from cultural power. To challenge and transform the existing political order, he argued that it is necessary to engage in a “war of position” to contest the dominant cultural narratives and establish counter-hegemonic cultural forces. By winning the battle for hearts and minds through cultural struggle, social movements lay the groundwork for a transformation of political structures and systems.

While Breitbart and Gramsci emphasize recognizing the importance of culture in shaping politics, it is important to note that their underlying philosophies and motivations differ significantly. Breitbart, a conservative commentator and media entrepreneur, focused on using media and popular culture to advance conservative values and challenge the perceived liberal bias in mainstream culture, whereas Gramsci was concerned with analyzing power dynamics in society and developing strategies for achieving socialist transformation.

Moreover, the term “Breitbart Doctrine” is not widely recognized as a formal academic concept and is more commonly associated with the strategies and perspectives put forth by Andrew Breitbart and his followers. In contrast, Gramsci’s theories on cultural hegemony and the relationship between politics and culture have had a significant impact on critical theory, cultural studies, and social movements. While that fact appears to support Breitbart’s thesis, it only looks like that because of the confusion over the character of the prevailing cultural hegemonic forces; that hegemony is not in fact Marxist but progressive. The confusion feels calculated, but it it the result of a convergence of powerful forces: the ability of corporations to use culture to manufacture false perceptions and maintain false consciousness and the neoliberal organization of higher education that has transformed traditional intellectuals into organic ones.

The gravity of the moment requires that I turn from the moderation of the professional punditry to the necessary radicalism called for by the moment.

* * *

Misanthropy is a deep-seated dislike or distrust of people often characterized by a cynical or pessimistic outlook on human nature. The misanthrope may judge humans as corrupt, greedy, selfish, stupid, or violent—or all of these things. Such a person limits his social interactions on this judgment. Misanthropy is typically considered an emotional or psychological state, but there is no reason why it cannot be characteristic of a political-ideological orientation or movement. Indeed, the evidence tells us that it is.

It might sound strange to consider the possibility that those who dislike and distrust people can at the same time organize as a movement—I’m reminded of Bill Hicks’ bit about new political party, the “People Who Hate People Party,” who have troubling coming together—, but consider that the character of identity politics is just that: the organization of like-minded people in opposition to others whom they treat as an organized group, whom they politicize. Progressives pitch their beliefs and actions—disguise their authoritarian desire and transgressive praxis—as representative of a political and social philosophy that emphasizes the need for continuous social reform and improvement. The very name suggests the attitude that society can and should progress towards greater equality, justice, and wellbeing for all individuals—this achieved through science and technology and more responsive government and social institutions.

The definition of progressivism is only surface. Substantively, progressivism is a form of selective misanthropy, its elitism rooted not only in the self-perceived superiority of the progressive personality, but also in a pessimistic view of humans and their impacts on other humans and on the environment. Progressives desire not the administration of things so much as the administration of people, because people are the problem. People are not up to self-government because they are base and stupid. The people are mouth-breathers. They’re a “basket of deplorables,” to quote the progressive who lost a presidential election to one. The Democratic party is truly the People Who Hate People Party.

As individual pathology, and as ideological standpoint, the misanthropic orientation of progressivism is selective in the sense that not all groups are viewed with the same degree of hatred and derision. The selectivity of its misanthropy indicates the political character of progressive ideology. The progressive rhetoric of social justice attempts to mask its politics. But an essential fascism lurks beneath all of it. In this blog, I analyze this political character of the moment by exploring the tension between progressivism, the political-ideological and policy standpoint associated with technocratic desire to administer human life, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, humanism, the Enlightenment view of humans as cooperative and reasonable—these things not being in contradiction with nature—and therefore capable of managing their own affairs free of corporate state control.

Indeed, one of the essential differences between conservatives, liberals, and on the one side, and progressives on the other, is that the conservatives and liberals oppose actions and ideas that are harmful to people and human freedom, whereas progressives loathe people and the fact that they have ideas. This tension is crucial to describe and grasp at this pivotal moment in history; the major difference between, on one side, all Democrats and the establishment Republicans, what some are calling the Uniparty, marked by its authoritarian and illiberal policies and rationalizations, and across from them, the populist-nationalist movement, which embodies the revival of democratic-republican politics and expresses a desire for the restoration of humanist and liberal values, is the progressive attitude.

* * *

Before moving to the analysis of progressivism and its misanthropic character and the relationship of these to the governance system, what I describe elsewhere as the “New Fascism,” I need to sketch the deep structures that support the new fascist situation, namely corporatism and the capitalist mode of production. This needs to occur because observers, on the right and left, falsely portray the corporate state and its expression in progressivism as a form of socialism. Corporatist arrangements are in fact the opposite of socialism. Socialism is a political economic system emphasizing the collective ownership and democratic control of the means of production and distribution of goods and services. Under socialism the economy is owned and controlled by workers rather than by private individuals or corporations. The goal of socialism is the empowerment of people and the elimination of significant economic inequality.

Corporatism is a political and cultural response to the inherent instability of the capitalist mode of production that replaces democratic processes and individual autonomy with administrative and regulatory controls. Some corporatist systems feign democratic norms; the appearance of democracy serves a hegemonic purpose by manufacturing the consent of the governed. But corporatism is a capitalist expression that negates the liberal attitudes and values that grow alongside of capitalism defending and justifying property rights. That corporatist arrangements negate liberalism does not make them socialist. Indeed, socialism would make possible a greater realization of the liberal values of cognitive liberty and freedom of conscience and of association and privacy extolled here on Freedom and Reason. Moreover, any socialism worthy of the people who should make it would have humanism as its beating heart, not the misanthropy that corporate state arrangements engender among its subjects.

So what is corporatism? Corporatism is a sociopolitical order emphasizing the organization of society into corporate groups, such as business, labor unions, and other interest groups, all appearing to work together to achieve common goals. The government plays the role of mediating disputes between groups and facilitating cooperation and collaboration among them. This can take the form of policies designed to promote economic growth or social welfare, as well as laws and regulations that regulate the behavior of these groups. While socialism, focused on meeting the basic needs necessary for human wellbeing and self-actualization, emphasizes the administration of things not people, corporatism emphasizes the administration of people and subordinates popular interests to private ones. While socialism emphasizes democratic and deliberative control for the sake of people, corporatism stresses the bureaucratic management of people in administrative systems and technocratic arrangements for the sake of profits. Although corporatism may appear as social democratic or authoritarian, all corporatism is an expression of the capitalist mode of production in its corporate or late phase, that is, capitalism where corporations are the dominant institutions.

Corporations have existed for centuries; however, for most of their existence, corporations have been answerable to a sovereign, using the principle of quo warranto, whether the sovereign is a monarch under absolutism, or the citizen under republicanism. Quo warranto is a legal concept that is used to challenge the legal authority or legitimacy of a person or entity that is exercising some form of public power or authority or private power or authority that effects public interests. It allows a court or government authority to require that the entity in question provide evidence of legal authority to hold a particular office or perform a particular function.

This rule as applied to corporate power was severely weakened in the late nineteenth century when courts defined corporations as legal persons. For background on this, I recommend Joel Bakan’s The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, a critical and accessible analysis of corporations and their impact on society. Bakan explores the history of corporations and how they have gained significant legal rights and protections, often at the expense of individuals and communities. (See Michael Tigar’s Law and the Rise of Capitalism for a broader and legal history of capitalism and corporate power.) Over the next several decades, capitalist states adopted corporatism as a means of controlling society and suppressing dissent. The explicit idea was to create a system of economic and social organization based on the interests of different “corporations,” i.e., groups, rather than on the interests of individuals.

The roots of the idea of corporatism can be traced back to medieval guilds, which were organizations that regulated trade and industry in Europe during the feudalist period.* In the late nineteenth century, intellectuals and politicians saw in guilds a model for economic and social organization in the modern world. Instead of cooperatives of craftsmen and merchants, the new guilds would be based on corporatist arrangements among powerful organizations. Thinking about a new model of sociopolitical organizations was a response to the social and economic changes brought about by industrialization and urbanization. It was also a response to the clear and present danger socialist and communists movements represented to the capitalist mode of production. Corporatism was presented as a new model of economic and social organization emphasizing collective interests over individual interests without changing the property structure. Thus the appearance of corporatism in its social democratic form portrayed as a way of promoting more effective and inclusive decision-making was, at its core, a ruse. By incorporating antagonistic groups into the political system of capitalism and its cultural representations, corporatist arrangements negated the threat socialism posed to the sociopolitical order that reproduces the capitalist mode of production.

The fact that corporatism is an essential component of fascist ideology, and the fact that the two are closely intertwined in history, should function to expose the ruse; but corporatist arrangements colonize the lifeworlds of the subjects they controls and the controlled subjects come to see these arrangements as progressive in a moral sense. Hence the political ideology we called progressivism, which, acknowledging cultural and political differences, parallels the social democracy that overlays European corporatism. Under progressive regimes, as under fascist regimes, the state acts as a mediator between different corporate groups, such as business, labor unions, professional associations, and identity groups, to achieve national unity and promote the interests of the corporate state (which are in fact transnational). This often involves the creation of state-sponsored organizations that bring together representatives of groups to coordinate economic policy and promote social welfare for the sake of maintaining the status quo. Corporations maintain control over these groups and use them as a means of entrenching its power and promoting ideology. As times this involves suppressing dissent and using intimidation and violence to maintain control over the population. Surveilling populations and managing individuals in bureaucratic systems are constant features of corporatist arrangements.

The new fascism is the result of the growth and development of corporatism and the attendant political-ideology of progressivism in the United States. The drive for corporatist arrangements emerge in the wake of the Civil War during the period of Redemption, when the slavocracy that corrupted the republic early in its development, represented by the Democratic Party, ended Reconstruction and reconfigured itself as the corporate state. As I discuss in Richard Grossman on Corporate Law and Lore, progressivism was in competition with the populism of the Republican Party, which has emerged to challenge the slavocracy and restore and deepen democratic-republican traditions, which it had some success in doing during the period of Reconstruction. It also enjoyed some success in the period between WWI and WWII, for example in restricting immigration. But during the New Deal period, progressivism was institutionalized and corporatist arrangements became the operating system of post-War capitalism. With considerable inertia behind them, populist movements continued to succeed in crucial areas of cultural and social live, for example in the civil rights, feminist, and free speech movements. Moreover, the chaotic nature of capitalist dynamics and the emergence of new communications technologies brought about a series of legitimation crises. It is in this context that the New Fascism emerges to regain control over the project to dismantle republicanism and establish a totalitarian world order.

In this analysis I have several guides. I will reference them throughout this essay. But among the most influential is Franz Neumann and his Behemoth: The Structure and Practice of National Socialism 1933-1944. Neumann provides there an analysis of the Nazi regime in Germany and its structure and social logic. Neumann argues that the Nazi regime utilized corporatist ideas and practices to create a tightly controlled society organized around the needs of the state, which was the projection of totalitarian monopoly capitalist arrangements. Neumann’s analysis focuses on the role of the corporate state in mediating conflict between different interest groups and coordinating economic activity. He argues that the Nazi regime utilized a system that was based on the integration of large industrial corporations into the state apparatus which allow the regime to control the economy and use it as a tool for furthering its political goals, goals that aligned with those of financial and industrial power.

Another influential figure on my thinking is Antonio Gramsci, especially his notion of the “extended state” (or “integral state”), which refers to his theory that the state is more than just a formal institution with a set of bureaucratic and legal structures, but includes a range of civil societal institutions, such as churches and schools, as well as cultural organizations, that help to maintain the dominant ideology and provide a totalistic system of social control that does not depend on violence. For Gramsci, the state is more than just a formal institution with a set of legal and bureaucratic structures. The ruling class uses these institutions and organizations to promote its own interests and ideology, and to ensure that the working class is effectively disempowered. The education system is a tool to indoctrinate students with ideas that reflect those of the ruling class, while the media promotes a particular worldview that reinforces the status quo. Gramsci’s theory of the extended state emphasizes the importance of understanding the complex ways in which power is exercised and maintained in society and the need for a comprehensive approach to social and political change.

* * *

The hysteria over climate change provides an instantiation of the misanthropy of progressivism. Progressives who hold a misanthropic view argue that we need to limit human impact on the environment in order to prevent further damage to it. This generates policies that restrict human activity and limit human freedom in the name of an abstract project to protect the planet.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that progressives tend to view humans, left to their own devices, as more parasitic than beneficial to the planet. One of the key tenets of progressivism is that humans are responsible for many of the social and environmental problems progressives identify and, frequently, invent. They depict the concerns of the proletarian masses as ignorant, bigoted, and racist. They point to climate change, deforestation, pollution, and resource depletion as evidence of the reckless power of the common man—while ignoring the corporate structure that drives the industrial treadmill of production. They demand governments take collective action to address these issues and to prevent further harm to the planet—action that necessarily involves limiting human freedom, providing corporations with more justifications/rationalizations for extending mechanisms of social control and establishing new ones. The intervention progressives demand involve restricting and eliminating practices that improve the lives of billions of people across the planet.

Consider two proposed solutions to environmental problems: reducing the use of fertilizer and fossil fuels. Whether addressing these will provide solutions to the problem, and leaving aside the question of whether there is a problem, limiting the use of either will negatively impact other aspects of society, such as food supplies and home heating, both of which are of great importance to working people. Recognizing that excessive fertilizer use can have negative environmental effects, responsible use of fertilizers is nonetheless vital for food production. Reducing fertilizer use reduces crop yields resulting in food shortages, which is especially devastating to developing countries where hunger and poor nutrition are already problems. Reducing fossil fuel leads to higher energy prices and reduced availability of reliable energy sources. While there is an obvious place for new and renewable energy sources, the energy mix needs to be managed carefully to avoid negative impacts on people.

You can hear in the rhetoric and see in the policies being proposed and implemented by progressives and social democracies the reductive mentality that not only portends harm to people but is already harming them. Consider the throughput of the shift to electric vehicles (EVs). The trend towards electrification of transportation is gaining momentum around the world, and many governments are taking steps to encourage and mandate the use of electric vehicles as part of their efforts to reduce emissions and combat climate change. Policies are being developed around the world not only to encourage the use of EVs, but also to mandate their use. Governments are implementing vehicle emission standards intended to induce—i.e., coerce—consumers into buying EVs. Policies will require automakers to produce EVs or meet emissions targets likely only achievable with EVs. Some countries have already announced plans to ban the sale of gas-powered vehicles in the coming years. Norway has set a goal to phase out the sale of new gas and diesel-powered cars by 2025. Great Britain has set a goal to ban the sale of new gas and diesel-powered cars by 2030.

To support the shift to EVs, governments are directly investing in or providing subsidies to private companies to build new infrastructure, including the installation of charging stations across the landscape. However, the production of batteries and the mining of the materials needed for the production of EVs and associated infrastructure carry unacknowledged negative environmental impacts, including resource depletion and environmental pollution. Lithium-ion batteries are the most common type of rechargeable batteries used in EVs. These batteries use a combination of lithium and other metals, such as cobalt, nickel, and manganese, to store and release electrical energy. The production and mining of lithium, as well as the discarding of spent batteries, carries significant environmental impacts, including water scarcity, soil contamination, and habitat destruction.

Additionally, while electric vehicles themselves produce little or no emissions, most of the electricity generation used to build them and charge them comes from fossil fuel-powered sources—the burning of coal, gas, and oil. Of course, given the nature of the global economy, dirty generation of energy can be moved around, giving the illusion of greener environments. We see this as well for other industries. But this ignores the reality that earth is a system. A more holistic approach is needed to address these challenges, rather than simply promoting electric vehicles as a solution. Alternative approaches to the challenges we face, namely nuclear, is stubbornly resisted by progressives. Solar and wind power cannot provide the energy needed for the billions of people who live on the planet to live decent lives.

Saving the planet from the parasitic human species is driven by the tendency among progressives to catastrophize. Catastrophizing is a cognitive distortion characterized by a tendency to interpret situations or events in a pathologically negative and exaggerated way. It is a type of thinking that leads to heightened anxiety and stress, these feeding on themselves, recycling and amplifying their energies, corrupting internal and external sense-making systems. We see catastrophizing in the hyperbole of total collapse of global ecosystems, mass extinctions, or runaway global warming. This mindset can lead to feelings of despair and powerlessness. However, when the desperate and powerless do something about it, their actions often manifest as hateful and useless exercises in interfering with the right of others to travel, the destruction of property, including famous works of art, and self-harm.

Action of this sort manifests as cultish behavior. Extinction Rebellion (XR), for example, known for its use of nonviolent direct action tactics, including blocking roads and bridges and disrupting traffic to draw attention to what its members see as an urgent need for action on climate change. These actions, which interfere with the human right of individual to travel unmolested, do nothing to raise awareness about an issue of which everybody is already aware. XR actions do, however, generate and amplify antagonistic attitudes among the majority about the issues the cult uses as its rationale for emotional expression (such aesthetics are also obvious in the Antifa and Black Lives Matter cults). Contrast this with humanism, which believes that humans are capable of living in harmony with the environment and that we should focus on promoting sustainable practices and technologies that allow us to thrive without causing undue harm to the planet. XR, which is an instantiation of the progressive mindset, sees people as a problem. Humanists see people as the solution and the point of politics.

* * *

Progressivism promotes a pessimistic view of humans as inherently harmful to the environment. Insistence on man’s destructiveness is evidence of the misanthropic reflex, and the reductive mentality of this view plays a major role in blinding people to more holistic approaches to managing technologies in light of the planet’s carrying capacity. I call this misanthropy selective in part because it focuses on the negative aspects of human behavior, while ignoring the positive contributions that humans have made to society and the environment, but does so only with respect to certain developments and groups. If people believe that humans are inherently destructive, then they may feel that there is little that can be done to change the course of history—until a way can be found to make the evildoers go away.

So, while misanthropy can lead to apathy and a sense of resignation, which can ultimately hinder progress towards a more just and sustainable future, and indeed the myopia of the misanthropic worldview is associated with sense of hopelessness and despair, which do objectively undermine efforts to address social and environmental problems, this state of mind at the same time produces anger and hatred which, in progressivism, is sublimated as demagoguery and aggressive and uncompromising activism. It’s here that the authoritarian personality that marks the progressive mentality becomes obvious. By eschewing rational argument and facts, and appealing instead to the emotions, fears, prejudice, and resentments of segments of the public, many of these manufactured by virtue of elite control over the means of intellectual production, progressives pit citizen against citizen.

Progressives are ideologues, rigidly adhering to a particular ideology comprised by a narrow set of beliefs, and they express this ideology to the point of being dogmatic and inflexible. Ideologues are people who are highly committed to a particular worldview or political agenda, viewing the world through a predefined and highly structured set of beliefs and values—one untethered to universal ethics and morality. The ideologue is unwilling to compromise or engage in constructive dialogue with those who hold different viewpoints; he is stubbornly reluctant to consider alternative viewpoints or evidence that contradicts his beliefs. That his worldview is set in these ways makes him resistant to reason. Even while he denies it, quick to label people or ideas that don’t fit neatly into the framework as enemies or threats, he sees the world in terms of clear-cut categories and binary oppositions. At once highly effective at promoting the system and mobilizing support for it and prone to extremism, intolerance, and oversimplification, the ideologue is dangerous is left unchecked.

As demagogues, progressives use emotional appeals to stir up the passions of their followers. This is achieved by demonizing certain groups of people—manufacturing enemies—and blaming them for society’s problems. Demagogues deploy hyperbole and inflammatory language to create a sense of crisis or urgency, appealing to identity politics to build a sense of solidarity among their supporters while separating them from others. Demagoguery is a powerful tool for mobilizing large numbers of people and rallying them around a cause or ideology, But it’s dangerous and divisive, particularly if and when it leads to the persecution or marginalization of certain groups of people. Demagoguery has been associated with authoritarianism, the erosion of democratic norms and institutions, and repression. These developments are in turn functional to the corporate state project to replace systems of self-government with those of administrative and technocratic control.

* * *

By focusing solely on the negative impact of human activity, rank and file progressives overlook the many ways in which humans have positively contributed to the world around us. Humans have created art, music, literature, and other cultural artifacts that have enriched our lives and brought us together as a species. Here progressives will object and appeal to their love of these things. They do this while degrading the creative output of the people they distain while embracing the most coarse and simplistic of forms of art, music, and literature. Attracted to the products of the popular culture industry (with the popular a manufactured sensibility), audio-visuals engineered to tap D2-like dopamine receptors, and simplistic imagery and writing to convey the agendas of various and reductive identities, the rank and file decry the art, music, and literature of European civilization as overly complex, rigid, stale, and white supremacist.

The elite among the progressive establishment views technology as a means for reducing human agency and pulling the masses under the control of the technocratic apparatus of the corporate state, problems to be managed by administrators and bureaucrats. The rank and file cannot grasp technological development in a democratic society as a means for overcoming limitations—a development that depends on exploiting the planet’s natural resources. Here, the misanthropic impulse is not only morally wrong and counterproductive, but dangerous. However, dangerous as well, perhaps even more so, is the elite understanding of technological development as a means of overcoming limitations to wealth production—for removing the obstacles thrown before it by authentic popular sentiment and action.

Not only in the sense of misanthropy as the character of a person who dislikes or distrusts humankind and generally has a negative view of people and society such that he may even withdraw from social interactions and avoid human contact, an attitude that appears among progressive individuals during perceived crises, but also in the general view of humankind as cruel, selfish, and stupid and therefore worthy of social control and thought suppression, progressivism is essentially misanthropic in orientation. Whether subaltern or elite, at his core, the misanthrope is anti-humanist in his sensibilities. Anti-humanism is a chief characteristic of the fascist attitude.

* * *

Recent history is teaming with illustrations of the anti-humanist standpoint of Democrats in particular. For example, the character of the mass hysteria surrounding the coronavirus pandemic exposed the deep personal misanthropy of those identifying as progressivism. When a group of people loathe some thing, they expresses a strong desire to avoid it or to remove it from their lives. This manifests in various ways, such as avoiding people or situations associated with the object of their loathing, and actively working to eliminate it from their environment. That a pervasive attitude of loathing, the expressions of disgust that marked the nature of the panic hardly needs examples, but I will briefly touch on its character here because it goes to the overall argument.

During the pandemic, progressives portrayed human beings, especially conservatives, but also children, as disease vectors. The loathing of humans was exhibited in the intense anxiety felt at being around people and places where people were, a phobia that manifested at times as disgust. Progressives expressed a deep aversion, even repulsion, towards others, insisting that people cover their faces, sanitize their environment—even sanitize their bodies by submitting, and offering up their children, to an experimental mRNA gene therapy. At the same time, they were deeply suspicious of actions taken by President Trump, for whom they harbor a special loathing since the president represented the populist democratic and republican values at challenge fascist structures. With the same intensity that Democrats urged Americans to take the vaccine under the Biden regime, they warned of the “Trump vaccine.” And medicines with anti-viral properties advocated during that period—hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and ivermectin—were derided as “fish tank cleaner” and “horse paste,” while Big Tech censored and de-platformed those who discussed the scientific literature and personal experiences concerning their use.

Crucially, progressive misanthropy comes with faith in scientism, the religion of corporate statism. The religion works by endorsing as “the science” only those pronouncements uttered by approved physicians and scientists, “the experts” the representative of the medical and scientific-industrial complexes. One finds this faith at the heart of the long history of progressivism, for example with the progressive commitment to eugenics, a scientistic endeavor rooted in misanthropy, only derailed in particular;ar instantiations by the horror of the Nazi holocaust. You will recall that the eugenicists believed that people were born with genetic structures that explained attitudes and behaviors associated with social advances and social problems. Some people have desirable genetic traits that should be promoted, while others have undesirable traits that should be eliminated. Scientists and policymakers could thus improve the genetic quality of the human population through selective breeding or, in the future, genetic engineering. We see it today in the progressive desire for trans-humanism, which takes many forms, including the cybernetic desire to fuse man and machine, shed the body, and to escape into virtual worlds.

As noted earlier, conservatives—the “deplorables”—were among those who were looked upon as especially troublesome. Again, it is in the character of the personality type of those attracted to progressivism to not merely disagree with those who hold beliefs or values that are opposed to their own, but to loathe individuals or groups of people who hold what are for them objectionable and offensive views, perceiving those who hold such views as having harmed others or potentially harming others such that they need to be controlled and marginalized. The coronavirus pandemic afforded progressives an opportunity to impose restrictions on those they most loathe. Those who sought to continue life in freedom were characterized as mouth-breathers and criminaloids.

These attitudes indicate the authoritarian personality Erich Fromm describes in his 1941 Escape from Freedom. Fromm argues that human beings have a fundamental need for a sense of security and belonging, but that these needs can come into conflict with the situations of individual freedom. With modernity comes the decline of traditional social structures and the rise of individualism has led to feelings of isolation and anxiety among the insecure and those with dependent personality types. This situation causes some people to seek escape from their freedom through authoritarianism, conformity, and destructiveness. Fromm theorizes that it is those individuals who lack a strong sense of identity and purpose who are particularly vulnerable to these forms of escape, as they may feel a sense of powerlessness and insignificance in the face of the challenges and complexities of modern life. The seek to escape these feelings into a world of control. In short, the loathing they feel for others in their misanthropic sensibilities is a self-loathing that causes them to repress themselves. Those who insisted others engage in irrational actions, such as mask wearing and experimental mRNA injections, were most eager to engage in these actions themselves.

This attitude is the mark of the fascist impulse. It is no accident that eugenics was embraced by both progressives and fascists (in fact, the Nazi eugenics program was adapted from the eugenics programs of Germany’s progressive and social democratic neighbors, as well as the United States). It is no accident that progressives today are the first to advocate for the pharmaceutical and surgical methods that percent patients of confused and vulnerable people—even children. Sublimated belief in the superiority of one’s own group and ideological system over all others is common across fascistic ideologies. Of course, such a belief is not exclusive to fascism; beliefs that resemble this are nonetheless fascistic in character (Islam is the paradigm, but there are others). The personality is marked by a desire to suppress dissent and scapegoat groups including the use of violence or other coercive tactics to enforce conformity to the agenda. We see it at the elite level of censorship, deplatforming, disciplining, and dismissals. We see it on the streets with Antifa and Black Lives Matter.

* * *

Central to fascist thought is the idea that the individual exists to serve the state and that the state’s authority is absolute and above reproach—as long as the Party (Democrats) is in charge. Emphasizing the supremacy of the collective over the individual, fascism is thus a form of anti-humanism. Humanism emphasizes the importance of individual freedom, equality, and human dignity. Fascists view these values decadent and destructive. They emphasize the need for hierarchy and obedience to authority—as well as censorship and other forms of repression. Fascism’s anti-humanism is thus reflected in its negativistic attitudes towards individual rights and freedoms. All this manifests in progressivism as a loathing of the Enlightenment and Western values, which are depicted as colonialist and racist.

Rejecting the concept of individual rights, fascists instead emphasize the importance of collective duty and obedience to the state—again, as long as the Party is in control. In fascist regimes, the state exercises near-total control over all aspects of society, including cultural production, economic institutions, the education system, and the mass media. Because fascism is a mode of control overlaying the capitalist mode of production in its corporatist phase, the state being discussed here is the corporate state. In corporate state systems, just as in other authoritarian systems, individual liberties are restricted and dissenters disciplined and excluded. That this is where progressives are at should be obvious in the attitude of congressional Democrats on the House Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government, a body organized by populist Republicans that is routinely exposing the vast deep state conspiracy to leverage social media utilities to suppress information critical of election integrity, the coronavirus pandemic, the medical-industrial complex, and other corporate state projects.

The anti-humanism of fascism is often coupled with a strong emphasis on militarism and the glorification of violence. This should be obvious in the overwhelming support of progressives for the Democratic Party march to war in Eastern Europe and its general lust for all things military. After giving tens of billions of dollars in military assistance to Ukraine in order to advance NATO’s proxy war against Russia, President Biden, overwhelming supported by progressives, especially younger progressives, requested billions of dollar more in military spending over last year’s budget. His budget called for 886 billion dollars in overall military spending for fiscal year 2024. That’s just base spending on the military-industrial complex and it’s already more than half of the discretionary spending Some 170 billion of Biden’s proposed military spending is for weapons procurement—ships, tanks, planes, bombs, missiles, etc. He is also requesting 38 billion for nuclear weaponry. This comes after the Pentagon failed its fifth consecutive audit (the Pentagon still cannot account for more than half of its trillions of dollars in assets). These are the causes of World War III. (For details of the latest budget fight, see my Notes on The Macroeconomic Situation and Various Theories, with Commentary on the Washington Debt Limit Panic).

“The growing proletarianization of modern man and the increasing formation of masses are two aspects of the same process,” writes Walter Benjamin in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” published in 1936. We must listen to Benjamin; he is teaching us how to see fascism where it exists in whatever form by grasping what it is and what it does: “Fascism attempts to organize the newly created proletarian masses without affecting the property structure which the masses strive to eliminate. Fascism sees its salvation in giving these masses not their right, but instead a chance to express themselves. The masses have a right to change property relations; Fascism seeks to give them an expression while preserving property.” That this is also the goal of progressivism must not escape consciousness. Nor should the fact that corporatism underpins both fascism and progressivism. It appears that, given the chaotic nature of capitalism, and the oppressive character of corporate bureaucratic arrangements, given enough time, progressivism becomes fascistic, but a new fascism, not the old one.

As progressivism is the ideological projection of the corporate state and corporatist arrangements, this explains the obsession with identity politics on the so-called left and the use of art, music, and literature as propaganda. “The logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life,” writes Benjamin. “The violation of the masses, whom Fascism, with its Führer cult, forces to their knees, has its counterpart in the violation of an apparatus which is pressed into the production of ritual values.” Here we have to make an adjustment to the thesis to account for the development of the system. As Sheldon Wolin told us in his 2008 book Democracy, Inc.: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism contemporary American democracy has been fundamentally transformed into a system of “managed democracy” or “inverted totalitarianism,” a situation in which the state and corporate power have merged to control and manipulate the political process.

The same effect is achieved at any rate: “All efforts to render politics aesthetic culminate in one thing: war. War and war only can set a goal for mass movements on the largest scale while respecting the traditional property system. This is the political formula for the situation. The technological formula may be stated as follows: Only war makes it possible to mobilize all of today’s technical resources while maintaining the property system.” As Benjamin notes, “the Fascist apotheosis of war does not employ such arguments.” But, still, futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti told the artists and poets of futurism to remember the “principles of an aesthetics of war so that your struggle for a new literature and a new graphic art … may be illumined by them!”

Benjamin understood that, as horrific as his views were, Marinetti enjoyed the “virtue of clarity.” Not merely anticipating but envisioning the trans-humanist desire, Marinetti wrote about the “metallization of the human body” in his 1909 article “The Futurist Manifesto.” Marinetti believed that technology and industrialization could transform human beings into powerful, machine-like beings, and that this transformation was necessary to break free from the limitations of traditional society and culture. “We will sing of the great crowds agitated by work, pleasure, and revolt; the multi-colored and polyphonic surf of revolutions in modern capitals,” he wrote. He sought to deliver Italy from its traditional intellectuals. He dreamt of erasing history, of razing museums and cemeteries and “their sinister juxtaposition of bodies that do not know each other.” “We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice,” he said of the Futurist movement. He celebrated “the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.”

Marinetti aimed to erase conventional boundaries between the inorganic and the organic, between living beings and the mechanical world. These “formulations deserve to be accepted by dialecticians,” Benjamin insisted to his comrades. “To the latter, the aesthetics of today’s war appears as follows: If the natural utilization of productive forces is impeded by the property system, the increase in technical devices, in speed, and in the sources of energy will press for an unnatural utilization, and this is found in war. The destructiveness of war furnishes proof that society has not been mature enough to incorporate technology as its organ, that technology has not been sufficiently developed to cope with the elemental forces of society. The horrible features of imperialistic warfare are attributable to the discrepancy between the tremendous means of production and their inadequate utilization in the process of production—in other words, to unemployment and the lack of markets. Imperialistic war is a rebellion of technology which collects, in the form of ‘human material,’ the claims to which society has denied its natural material. Instead of draining rivers, society directs a human stream into a bed of trenches; instead of dropping seeds from airplanes, it drops incendiary bombs over cities; and through gas warfare the aura is abolished in a new way.” To be sure, gas warfare has been banned—its horror replaced by the horror of DIME (Dense Inert Metal Explosive), which uses a carbon fiber casing filled with a mixture of explosive material and very dense microshrapnel made up of small particles or powder of a heavy metal such as tungsten.

C. Wright Mills grasped the capitalist drive to war in The Causes of World War III, published in 1958. Mills argues that the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union was leading the world toward a potential global conflict. He identified several factors that he believed were contributing to this situation, including the arms race, the militarization of society, and the role of the military-industrial complex in shaping foreign policy. Mills argued that the root cause of the conflict was not ideological differences between the US and the USSR, but rather a struggle for global power and influence.

In his 1956 The Power Elite, Mills argued that the United States, controlled by a small group of economic, political, and military elites who dominate the major institutions of American society, has developed a structure that is incompatible with genuine democracy. In The Causes of World War III, he expands his critique to include the global political and economic system. He argues that the concentration of power in the hands of a few has led to a dangerous international situation, in which the actions of a few key players can have catastrophic consequences for the entire world. Thus the characteristic of post-WWII context can bee seen as a fascistic need for war and conquest producing a culture of aggression and violence, which can be directed both inwardly towards dissenters and minorities, as well as outwards to other enemies.

For those who might object that I am extending Mills too far, I can respond by noting that it’s widely recognized that The Power Elite was influenced by Neumann’s Behemoth, summarized above as a detailed analysis of the political and economic structures of Nazi Germany that examines the ways in which banks and corporations were able to collaborate with the fascist regime to enhance and entrench their power and influence in and over society. Neumann’s book was highly critical of the concentration of power and the suppression of democratic institutions that characterized these arrangements. Mills drew on many of the same themes in his own critique of American society, identifying parallels between the concentration of power in Nazi Germany and the concentration of power in the United States. He argued that the same dangers of authoritarianism and suppression of democracy existed in both societies. The situation today represents the realization of Mills’ fears.

“The atrocities of The Fourth Epoch are committed by men as ‘functions’ of a rational social machinery—men possessed by an abstracted view that hides from them the humanity of their victims and as well their own humanity. The moral insensibility of our times was made dramatic by the Nazis, but is not the same lack of human morality revealed by the atomic bombing of the peoples of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? [Atrocities perpetrated by Democrat Harry Truman.] And did it not prevail, too, among fighter pilots in Korea, with their petroleum-jelly broiling of children and women and men? [Atrocities also perpetrated by Truman.] Auschwitz and Hiroshima—are they not equally features of the highly rational moral-insensibility of The Fourth Epoch? And is not this lack of moral sensibility raised to a higher and technically more adequate level among the brisk generals and gentle scientists who are now rationally—and absurdly—planning the weapons and the strategy of the third world war? These actions are not necessarily sadistic; they are merely businesslike; they are not emotional at all; they are efficient, rational, technically clean-cut. They are inhuman acts because they are impersonal.”

Fascism is a form of modern anti-humanism, emphasizing the supremacy of the state over the individual and rejecting the values of liberalism, including individual rights, freedom, and human dignity. Its emphasis on hierarchy and obedience to authority leads to the suppression of dissent and the glorification of violence. This poses a grave threat to personal autonomy and and human rights. Humanism emphasizes the value of human beings and the potential for their development, stressing the importance of dignity and freedom. This stands in stark contrast to the misanthropy of progressivism, which views humans as inherently acquisitive, avaricious, and destructive—in need of control. Progressivism is anti-humanist in its opinion that a significant proportion of humans as selfish and stupid and therefore not fit for self-governance.

* * *

The tension between humanism and misanthropy is evident in the debate over social progress. Progressives who hold a misanthropic view of humans argue that we need to impose strict regulations and policies to ensure that everyone is treated fairly and equitably, demands that in fact involve treating people unjustly and unequally by determining the fate of individuals on the basis of membership in historically and socially constructed groups—with the actual history replaced by an ideological one. Progressives justify discriminating against members of select groups by dehumanizing them using racially and other divisive speech. Eschewing the principle that a free society protects free speech, Progressives seek to emplace commissars to censor and de-platform—or to act in their stead (as we say recently at Stanford). Humanists, on the other hand, argue that we should instead focus on promoting individual freedom and responsibility, while ensuring that everyone has access to the resources and opportunities they need to succeed.

Ultimately, the tension between humanism and misanthropy reflects a fundamental philosophical divide over the nature of humanity and our place in the world. While progressivism is ostensibly motivated by a desire to improve society and protect the environment, at the core of the standpoint is a selective misanthropy evidenced by an overly negative view of humans and their impact on the world and a desire to transcend the born body (transhumanism and transgenderism). It is vital to recognize the many positive contributions that humans have made throughout history, even as we work to address the challenges that we face today. By embracing a more hopeful and inclusive view of humanity, we can inspire greater collective action towards a more just and sustainable future for all. This cannot be achieved by portraying people as the problem. As I have stressed many times on my blog, people are the solution.

In the Prison Notebooks, Antonio Gramsci criticized the American method of scientific management, also known as Taylorism or Fordism, and industrialism more generally, in relation to the “animality of man.” Gramsci argued that this managerial approach, which aims to optimize efficiency and productivity in industrial settings, treats workers as mere cogs in a machine and reduces them to their most basic and animalistic instincts. According to Gramsci, scientific management reduces human beings to their physical and instinctual capacities, emphasizing repetitive and monotonous tasks that require little skill or intellectual engagement. By focusing on the division and specialization of labor, this approach dehumanizes workers and robs them of their creative and intellectual potential. Gramsci contends that the American method of scientific management suppresses the full development of human capacities, reducing individuals to passive objects of production. It strips away their agency, individuality, and the possibility of self-realization (what Maslow called “self-actualization.” Workers become alienated from their work, their creative abilities, and their potential to contribute to society in meaningful ways. Gramsci sees in these processes the denial of animality within the context of the American system, which includes the logic of Puritanism, seen for example in the temperance movement.

Gramsci argues that the American system, influenced by Protestant ethic, promotes a rigid moral framework that seeks to suppress and deny human animality, a reductive animality produced by the industrial process and the logic of social control on this basis. Puritanism, according to Gramsci, emphasizes self-discipline, asceticism, and the repression of bodily desires and pleasures. This worldview and its attendant regimes create a moralistic and repressive environment that denies or undermines the natural and instinctual aspects of human life. Gramsci extends his critique to the temperance movement, which emerged in the United States as an effort to promote abstinence from alcohol. He sees this movement as an expression of Puritan values and the broader attempt to control and suppress human animality. Gramsci argues that such movements and moral frameworks perpetuate a distorted view of human nature, disregarding the legitimate needs, desires, and expressions of individuals. It portrays the human animal as dangerous and loathsome, a portrait that become sublimated in woke progressivism in the late capitalist phase of corporatism. This is the underlying source of the misanthropy I am describing in this essay.

In critiquing the denial of animality, Gramsci challenges the imposition of moralistic and puritanical norms that restrict and stifle human freedom and authentic expression. He advocates for a more holistic understanding of human nature that acknowledges and respects both the rational and instinctual dimensions of human existence. By recognizing and reconciling animality with the intellectual and creative faculties of humans, Gramsci suggests that a more balanced and liberated society can be achieved.

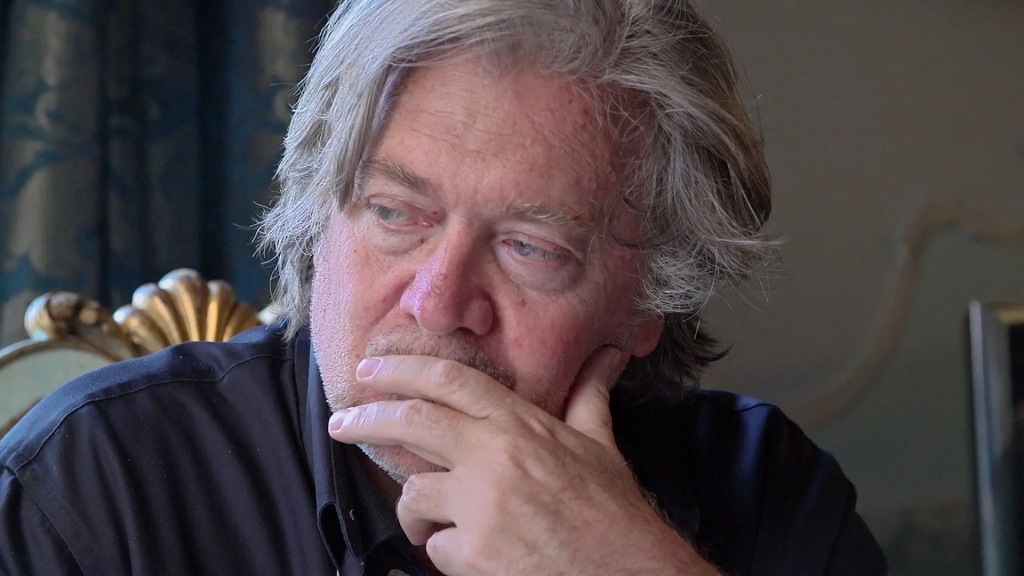

Whatever their differences, which are no doubt deep and profound, Gramsci’s desire was also Breitbart’s. You may recall that Steve Bannon was associated with Breitbart News for a significant period. Joining the organization in 2012, Bannon became the executive chairman of the media organization. During his time at Breitbart, he played a pivotal role in shaping its editorial direction and expanding its influence. Under his leadership, Breitbart became known for its populist and nationalist viewpoints, often aligning with the political right.

Today there is another convergence of what would on the surface seem to represent countervailing forces: the conservative right and the liberal left. But their spirit in populism brings Breitbart and Gramsci together. It may feel like a paradox, but it is necessarily union if we are to build a mass-based movement to reclaim democratic-republican praxis.

Endnotes

* The destruction of the medieval guild system was a complex and gradual process that took place over several centuries. As monarchs and the middle class gained more power and control over economic activity, they determined that the guilds were impediments to commerce and trade. Governments sought to break the power of the guilds by limiting their membership, imposing taxes and fees on them, or criminalizing them. More organically, the growth of capitalism and the emergence of new forms of economic organization, such as corporations and joint-stock companies, allowed for greater flexibility and innovation than the guilds, which were often bound by custom and tradition. New technologies and manufacturing techniques made it possible for goods to be produced more efficiently and on a larger scale, making the traditional skills and techniques of the guilds less relevant and valuable.