The most important thing to determine was the natural order in which the sciences stand—not how they can be made to stand, but how they must stand, irrespective of the wishes of anyone…. This Comte accomplished by taking as the criterion of the position of each the degree of what he called “positivity,” which is simply the degree to which the phenomena can be exactly determined. This, as may be readily seen, is also a measure of their relative complexity, since the exactness of a science is in inverse proportion to its complexity. The degree of exactness or positivity is, moreover, that to which it can be subjected to mathematical demonstration, and therefore mathematics, which is not itself a concrete science, is the general gauge by which the position of every science is to be determined. Generalizing thus, Comte found that there were five great groups of phenomena of equal classificatory value but of successively decreasing positivity. To these, he gave the names: astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, and sociology. —Lester Ward (1898)

I have been thinking about this analytical model for quite a while, indeed, for years now, sketching it at the beginning of my Foundations of Social Research class to clarify scientific theory, and while I am confident others have thought about this matter in this way before, I have not seen it specified in precisely this way. So I have decided to publish it on Freedom and Reason as the “Four Domains of Reality.” August Comte attempted this more than two centuries ago; however, his was exclusive of the humanist element in the social sciences and he left out psychology.

In today’s essay I present a different model (or heuristic) to facilitate the exploration of reality with the understanding that scientific truth can best be reached through the lens of four interdependent domains: the physical, natural, social, and psychological. Each domain emerges from and builds upon the previous one, establishing a hierarchy of complexity, each successive domain qualitatively different where the fundamental properties of the substratum remain unchanged except where social activity changes them. The framework I outline here is how I mentally navigate the intricate web of existence, recognizing both the distinctiveness and interconnectedness of each realm. Each domain comes with concepts and theories abstracted from its facts, unified by a commitment to scientific materialism.

At the foundation of this structure lies the physical domain, encompassing the fundamental elements of the universe. This domain is governed by the immutable laws of physics and chemistry, including organic chemistry (which forms a bridge to the successive domain of natural history), dictating the behavior of matter and energy. Here, the basic building blocks of reality—molecules, atoms, and fundamental particles—interact in predictable ways, forming the substratum upon which all higher levels of reality are possible. The physical domain provides the essential groundwork for the emergence of the natural world, yet it remains indifferent to the complexities that arise within its successors. While there are many scientists who have contributed to our understanding in this domain, I will note here Albert Einstein, who formulated the special and general theories of relativity.

The natural domain encompasses the living world, wherein biological processes transform inert matter into life. This domain is characterized by the presence of organisms and ecosystems and their developmental and evolutionary dynamics. While rooted in the physical principles of energy and matter, the natural domain introduces a new level of complexity through the processes of growth, reproduction, and adaptation. Life forms, from the simplest bacteria to the most complex multicellular organisms, navigate their environments through complex biochemical interactions and push their genomes into the future through a myriad of reproductive strategies. Despite being anchored in the physical, the natural domain exhibits properties that are qualitatively distinct, such as homeostasis and metabolism, illustrating the principle of qualitative emergence. As with physics, there are several notable scientists, but the one who stands above the rest is Charles Darwin, as he identified the mechanism by which life changes over time with his theory of natural selection.

From the natural domain arises the behavioral-social domain, in sociology a realm shaped by the interactions and relationships among sentient beings. This domain is defined by the structures and systems that humans create to organize and understand their collective existence. Culture, institutions, language, and social norms form the bedrock of social reality, enabling individuals to coexist, communicate, and cooperate. While rooted in biological imperatives and natural instincts, the social domain transcends them, giving rise to complex societal constructs and collective consciousness. It is within this domain that human beings negotiate their identities, roles, and shared meanings, creating a tapestry of social relations that cannot be reduced to mere biological interactions. A notable sociologist working in this domain is George Herbert Mead.

Before moving on to the domain of the mental life, I need to clarify the concept of the “social”; traditionally limited to the human species (its origins n the Latin word socii, meaning “allies”), it arguably warrants a nuanced understanding. On one hand, the human capacity for self-reflection and complex communication gives rise to a social world that is distinctly advanced. This world is characterized by intricate cultural, political, and economic systems that are underpinned by our unique cognitive abilities and experience as a species. Humans, through language and abstract thinking, create and manipulate symbols, enabling a depth of social interaction unparalleled in the animal kingdom. This level of social complexity is shared by few other species, with perhaps exceptions such as other apes, dolphins, and whales, whose behaviors suggest a capacity for sophisticated social structures and self-awareness.

In contrast, the social existence of humans as well as non-human animals can be understood in a broader sense. Many animals, including those with less complex brains, exhibit social behaviors essential for survival and reproduction. These behaviors range from the coordinated hunting strategies of wolves to the intricate hive activities of bees. While these social systems might lack the self-reflective component seen in humans and some other mammals, they demonstrate an inherent social organization driven by evolutionary pressures. Thus, sociality in this context refers to the collective existence and interactions within a species, contributing to their reproductive success. For this reason, it is important to acknowledge that social behavior is not solely the domain of large-brained animals. Insects, for example, despite their lack of a proper brain, exhibit highly organized social structures. Ants and bees, through their complex colony systems, engage in cooperative behaviors that ensure the survival of their communities. These social interactions, though not reflective in the human sense, demonstrate a form of collective intelligence that is crucial for their functioning and adaptation.

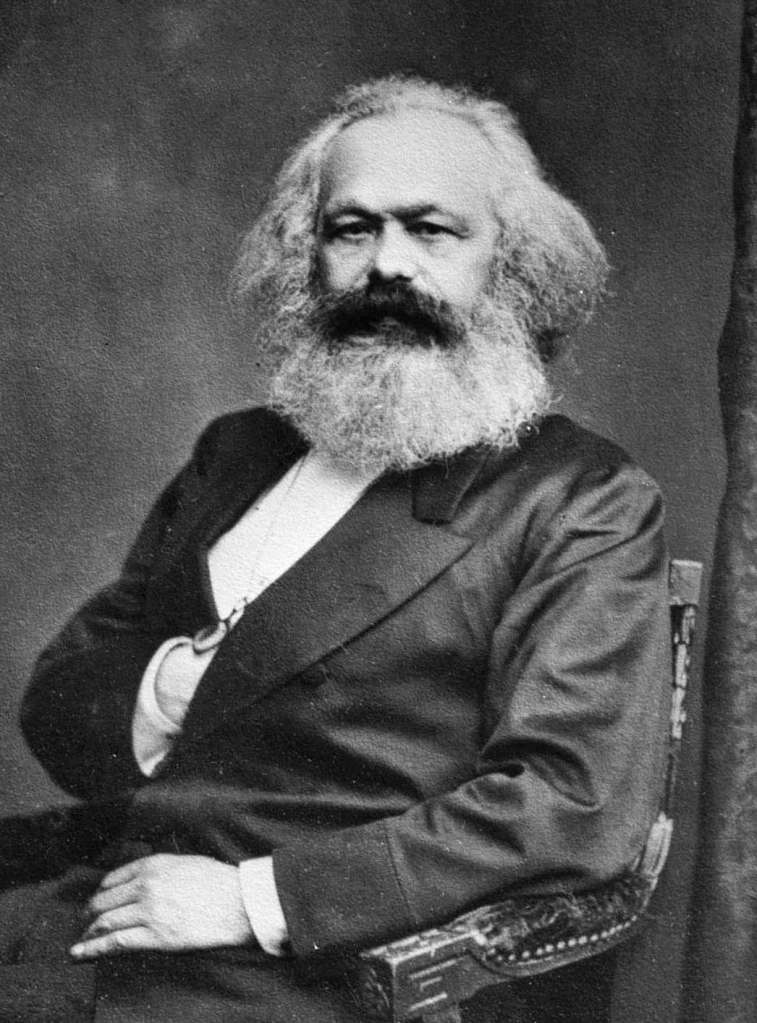

So, while the concept of the social in, e.g, in the work in Max Weber, implies a certain level of cognitive sophistication, it might not fully capture the breadth of social behaviors observed across species; it may therefore be useful to differentiate between the types of social interactions. Human sociality, with its reflective and symbolic dimensions, stands apart from the more instinctual and survival-driven social behaviors seen in other animals. Recognizing this distinction allows for a deeper appreciation of the diverse ways in which life forms interact and organize themselves within their environments. At the same time, as Karl Marx argued, human beings, like many other animals, are intrinsically and necessarily social; humans organize to collectively meet their needs, relations that exist independently of their will, in the same way that the relations among other species do not depend on their subjectivity.

That said, it is important therefore to keep in mind two Marxian observations. The first is from Capital (volume one, part 3—omitted from Soviet editions): “We presuppose labor in a form that stamps it as exclusively human. A spider conducts operations that resemble those of a weaver, and a bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality. At the end of every labor process, we get a result that already existed in the imagination of the laborer at its commencement.” Here, Marx is saying that, through socialization in a culture, a body of ideas, the architect inherits a symbolic system exists in the psychical domain, and this allows him to change the world intentionally.

The second observation to keep in mind is from the preface to the A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy: “In the social production of their life, men enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will; these relations of production correspond to a definite stage of development of their material productive forces. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.” Taken together, Marx is arguing that the structure raised in the imagination of the architect is a projection of his existence at a particular point in history in a particular type of social system.

The psychical domain emerges from the behavioral-social domain, but also the natural domain, since the human brain is a product of Darwinian evolution, representing the realm of individual consciousness and inner experience, all of which depends on the psychical for its electrical-chemical interactions. This is the mental life of our species. This domain encompasses the subjective aspects of human existence, that is cognition, emotion, and perception. Psychological phenomena, shaped by socialization and cultural context, possess an irreducible quality that distinguishes them from both the social structures and the biological substrates from which they arise. Consciousness is central to this domain, reflecting a level of complexity that challenges reductionist explanations. The psychological domain encapsulates the essence of what it means to be an individual, navigating the interplay between internal states and external realities. A major figure to note here is Sigmund Freud.

Each domain, while emergent from and grounded in its predecessor, maintains its unique characteristics and cannot be wholly explained by the principles governing the preceding levels. The physical domain sets the stage for the natural, which in turn provides the foundation for the social, culminating in the rich and intricate tapestry of the psychological, with direct relations from the natural to the psychological, substantially shaped by environmental experiences and symbolic communication. This hierarchical model underscores the principle of non-contradiction: no domain can violate the fundamental principles of the one it is rooted in but it can shape the substrata, in the case of humans intentionally. Physical laws remain inviolate within the natural world; biological imperatives persist within social constructs; and psychological phenomena, while distinct, do not contravene the social and natural conditions from which they emerge on modify it. For example, the current fashionable belief that a gender identity can exist that is incongruent with the gender of the organism is false because it stands in contradiction with the biological reality of gender in the human species, which is dimorphic and immutable. And while endocrinologists and surgeons can modify physiological processes and the appearance of secondary sex characteristics, these application of technology cannot change the subject’s gender.

The conceptualization or model of reality I have presented here is an attempt to offer a coherent basic framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of existence. It emphasizes the emergent properties and qualitative differences at each level while acknowledging the foundational continuity that links them. By recognizing the distinct yet interconnected nature of the physical, natural, social, and psychical domains, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity of the universe, our place within it, and how we think about it. This model encourages a holistic view of reality, one that respects the unique contributions of each domain while understanding the intricate dependencies that bind them together.

Here are a few strengths of the model: (1) Distinctiveness of each domain. By acknowledging the qualitative differences between domains, the argument avoids reductionism. This is particularly important in understanding phenomena like consciousness, which are difficult to explain solely in terms of lower-level processes. (2) Hierarchical structure and emergence. This feature captures the idea that complexity in the universe builds layer by layer, with each new layer introducing novel properties that cannot be fully reduced to the components of the previous layer. (3) Holistic perspective. The framework encourages a holistic view of reality, promoting an integrated understanding of how different aspects of existence relate to and depend on each other. This can be particularly valuable in interdisciplinary research and thinking. (4) Interconnectedness and non-contradiction. This feature of the model emphasizes that no domain can contradict the principles of the domain it is rooted in, providing a foundation for maintaining coherence across different levels of reality. This respects the integrity of each domain while recognizing their interdependence.

As with any system, and this is only a sketch here, there are areas in need of further clarification and exploration: (1) Clarification of boundaries. The distinctiveness of each domain is a strength, and it may be useful to further clarify the boundaries between them. For example, where exactly does the natural domain end and the social domain begin given instinct? I recognize that boundaries are sometimes context-dependent and fluid. (2) Dynamic nature of domains. Related to (1), these domains are not be static but rather dynamic and evolving. Detailing these processes add layers of complexity. For instance, how do changes in social structures influence psychological development over time? How might advancements in our understanding of one domain shift our understanding of another? (3) Examples and applications. Providing concrete examples of phenomena that exemplify the transitions between domains would help illustrate the argument more vividly. This would also demonstrate how this framework can be applied to real-world scenarios and point to directions in scientific inquiries. (4) Inter-domain interactions and potential theoretical/methodological incommensurabilities. While the argument touches on the interconnectedness of the domains, a deeper exploration of how they interact and influence each other would add depth. For instance, how do social factors influence psychological states, and vice versa? What are the feedback mechanisms between these domains?

I want to emphasize that this is a sketch of an argument I hope is promising for devising a compelling and useful way to grasp the complexity of reality through emergent domains, stressing the importance of domain-dependent methodologies (abstraction) and the possible cross-utility. This is the model, perhaps better pitched as a heuristic, that guides me in my study of reality. It balances the need for distinctiveness at each level with the necessity of coherence and non-contradiction across levels. To be sure, by exploring the boundaries, interactions, and dynamic nature of these domains further, the framework could be enriched, offering even more nuanced insights into the nature of existence, but as it is, it at the very least allows us to locate observed phenomena in various domains or across domains while avoiding explanations that suppose realities that contradict the domains out of which realities arise. Finally, as noted at the start, I don’t present this as an original way of thinking about reality, but having not seen it depicted this way (and this could be because of ignorance on my part), I wanted to share it with readers of Freedom and Reason to elicit feedback and insight.