“The people with real power are the ones who own the society, which is a pretty narrow group. If the specialized class can come along and say, I can serve your interests, then they’ll be part of the executive group. You’ve got to keep that quiet. That means they have to have instilled in them the beliefs and doctrines that will serve the interests of private power. Unless they can master that skill, they’re not part of the specialized class. So we have one kind of educational system directed to the responsible men, the specialized class. They have to be deeply indoctrinated in the values and interests of private power and the state-corporate nexus that represents it. If they can achieve that, then they can be part of the specialized class. The rest of the bewildered herd basically just have to be distracted. Turn their attention to something else.” — Noam Chomsky (2002)

In this essay, I address the fallacy of appeal to the authority of consensus (as opposed to truth), as well as ideological and political corruption, and pseudoscience in our knowledge-producing and sense-making institutions. One of the most frustrating things about being a scientist today is having to confront ideology, politics, and pseudoscience. This is not because the claims are difficult to debunk, but because one risks career progression, reputational harm, and even threats to his physical safety for exhibiting tenacity in commitment to science. I will pull a few topics from my past writings as examples of the problem. I begin with gender identity doctrine and the corruption of knowledge about sex differentiation, a topic I frequently address in essays on this platform.

Even in cases of intersex conditions—an unfortunate term for a scientific classification properly defined as disorders or differences of sex development (DSDs)—the sex of a mammal can still be definitively identified. Identification of gender has to do with gametes and the genetic sex type. An XY sex type or any variation on that side of the binary cannot produce female gametes. It follows that males cannot be women, the term we use to refer to adult female humans (we use other terms to refer to adult females of other species), any more than toms or gibs can be queens or mollies. DSDs are obviously not choices people make or subjective states of being. However, like any other medical condition, they should be accurately described, not rationalized by changing the meaning of gender for the sake of inclusion or kindness. Even though DSDs and trans-identifying individuals are not the same thing, correctly gendering them is based on the same logic.

To put this another way, a mammal, even one with a so-called intersex condition, is either female or male by definition of its developmental orientation toward one of the two reproductive roles. Humans are mammals. As such, our gender is constrained by the same evolutionary demands. The biological category remains binary; disorders simply represent variations within one of those categories, not a third sex. They are also exclusive categories; there is no in-between. This is not a matter of scientific consensus, but rather a brutal truth. Therefore, the term “intersex” should be jettisoned in educational settings; the reality that there are conditions that alter the outward appearance of individuals should be accepted, not rationalized ideologically or politically, or for the sake of sympathy.

A just society must state this clearly and often: Fairness must never be sacrificed for the sake of kindness or pity. I have in mind here the controversy over the recent Olympic Games, when two male sufferers of DSD were allowed to compete against women in boxing. The claim that the two males had always been regarded as girls and women, true or untrue, does not obviate the fact that they were always both males. Their situation, however unfortunate to ego or goal, cannot demand that women sacrifice the opportunities granted as exclusive to them based on the objective fact of sexual dimorphism. For experts to appeal to a consensus whereby males suffering from DSD are defined as women is therefore a fallacious appeal, since the self-evident truth is that they are not.

I have shown in my writings that the repurposing of the term gender, a synonym for sex for eight centuries, is an ideological-political project. Any individual can discover for themselves the history of these terms and who and what was behind the repurposing. The hijacking of the term was intentional and political. What remains true throughout this history is that it is not a scientifically valid differentiation of terms. It also shows how language can be used to undermine accuracy and precision in defining reality.

Thus, if a biology teacher tells his students something other than the truth of the gender binary, he is teaching pseudoscience. If he teaches the truth, but then says that a mammal may subjectively be something that objectively the mammal cannot be, then the teacher is speaking beyond the subject matter; he is entering the realm of spirituality. This is analogous to a biology teacher teaching about the soul, except that, in the case of gender identity, the claim that a male is a woman is falsifiable, even if the notion of gender identity as a subjective thing is not. Moreover, while there may be an organic basis to subjective claims, such as a schizophrenic claiming to be god, the subjective claim itself is a symptom of an illness, not an indication of a real entity. This is not a matter of consensus but of fact and reason.

To pursue the analogy further, the matter of souls is not altogether disallowed in education. However, teaching about the soul as an actual thing is properly reserved for a philosophy or theology class, where the question of its falsifiability is not an issue in ontological discussion. These are speculative endeavors, and it is no small matter given that billions of people believe in, as Freud would have it, illusions. It is for this reason that it’s possible to talk about the soul in the context of a social science class when studying things that people believe in, just not as actual things, not as scientific facts, apart from faith-belief. Faith-belief is a social fact (and a cognitive problem beyond the practical). The soul or things like it are not facts that exist independently of human thought. As suggested above, clinical psychologists may acknowledge that people have mistaken beliefs about their gender, but to teach that the substance of a mistaken belief can exist as a real thing, and therefore the belief is not mistaken, is an error of judgment. Yet many clinicians and teachers do this. In a clinical setting, it’s malpractice. This goes for the medical industry, as well.

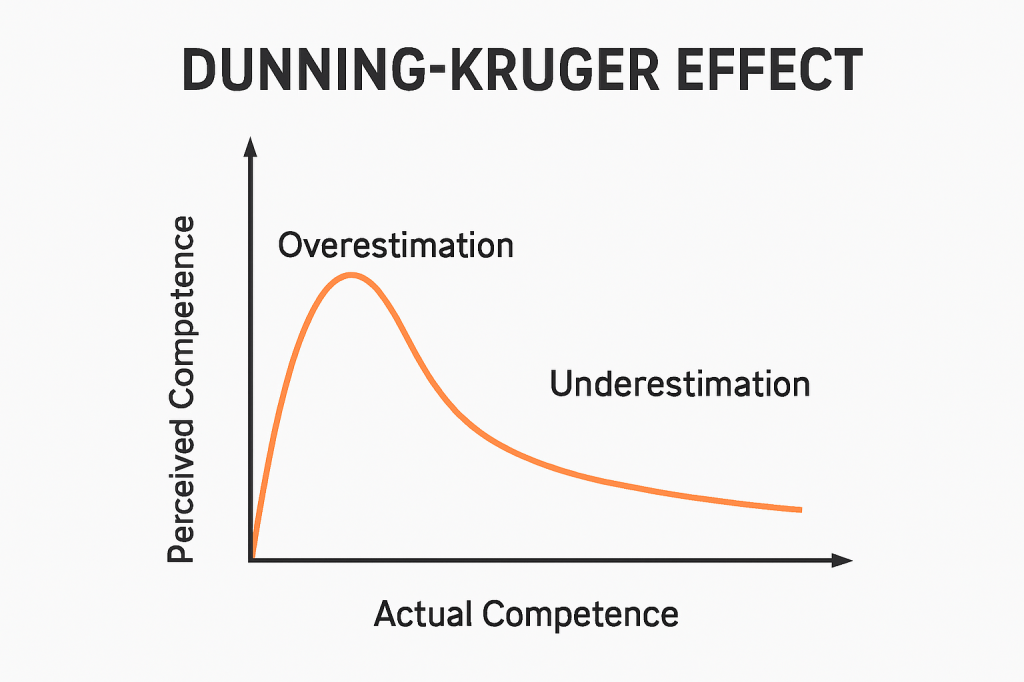

This brings us to the problems of ideology, ignorance, and incompetence. Here, I will draw an example from the teaching of criminal justice. If I know that the evidence does not support a claim of systemic racism in lethal civilian-police encounters, a claim that justified widespread violence during the summer of 2020, but I continue to teach my students that patterns in lethal civilian-police encounters are explained by systemic racism, then I am engaged in academic misconduct—and participating in the valorization of the impetuses for irrational dissent and illegitimate violence. If I don’t know that what I am teaching has been falsified by careful research, then I am ignorant or incompetent, which includes the problem of ideological corruption. If it is the former, then the educator needs to be educated. Once the evidence was clear on the question of systemic racism in civilian-police encounters, I revised my criminal justice lectures to reflect this change in knowledge. Culture and institutions should socialize the importance of self-education. Unfortunately, as I noted at the outset, it too often punishes those whose speech acts are deemed politically incorrect.

In the Soviet Union, the notion of speech acts as politically correct or incorrect referred to strict adherence to the Communist Party line—an expectation that one’s scholarship, scientific work, and teachings align with officially sanctioned ideology. The term was used among party members to signal whether a position was doctrinally acceptable rather than factually accurate. Ideas that were empirically true or rationally derived were condemned if they conflicted with orthodoxy, presented as the consensus view. Political correctness functioned as a tool of ideological discipline, reinforcing conformity and discouraging dissent or independent inquiry. An objection is that political correctness in the Soviet Union was rooted in authoritarian control rather than cultural or social sensitivity. But cultural and social sensitivity rationalize the same thing: the disciplining and punishment of independent minds arriving at judgments inconvenient for the ideological and political goals of the establishment and its functionaries.

The purpose of academic freedom and tenure is to shield knowledge production from ideological and political influence, either from those in power or majority opinion, both of which may be unconcerned with truth or mistaken about facts. At the same time, these principles protect incompetence and ideological corruptions. This problem can be checked by rational dissent from consensus. However, too often, the solution is checked by censorship, external and self-imposed. Left unchecked, political correctness creates environments where entrenched intellectual agendas, methodological laxity, or manipulated, selective, or weak evidence persist because they are insulated from scrutiny. The very structures designed to preserve independence can, in certain circumstances and under certain regimes, inhibit correction and truth-telling, making it difficult for institutions to respond when intellectual independence is eroded by ideological and political influence. The challenge, then, is to safeguard the autonomy necessary for genuine inquiry while developing internal mechanisms capable of addressing complacency and the slow drift from rigorous truth-seeking.

I will leave the question of how to achieve this for another day, since safeguarding can itself increase the pressure on teachers to adhere to standards that are objective but ideologically established, often in conjunction with moneyed power and political pressure (albeit this may be the lesser of evils). This will have to suffice for now: While it is appropriate to “teach the controversy,” ignorantly or knowingly presenting falsehoods as facts or truths is a problem in education. Optimistically, it should be enough to demand that teachers reflect on matters of integrity. Realistically, teachers are human, and like all humans, they are biased and prepared to self-deceive to protect cherished beliefs. It may be an intractable problem. How did Romain Rolland put it? “Pessimisme de l’intelligence, optimisme de la volonté” (“Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.”) Perhaps that alleviates one’s cynicism.

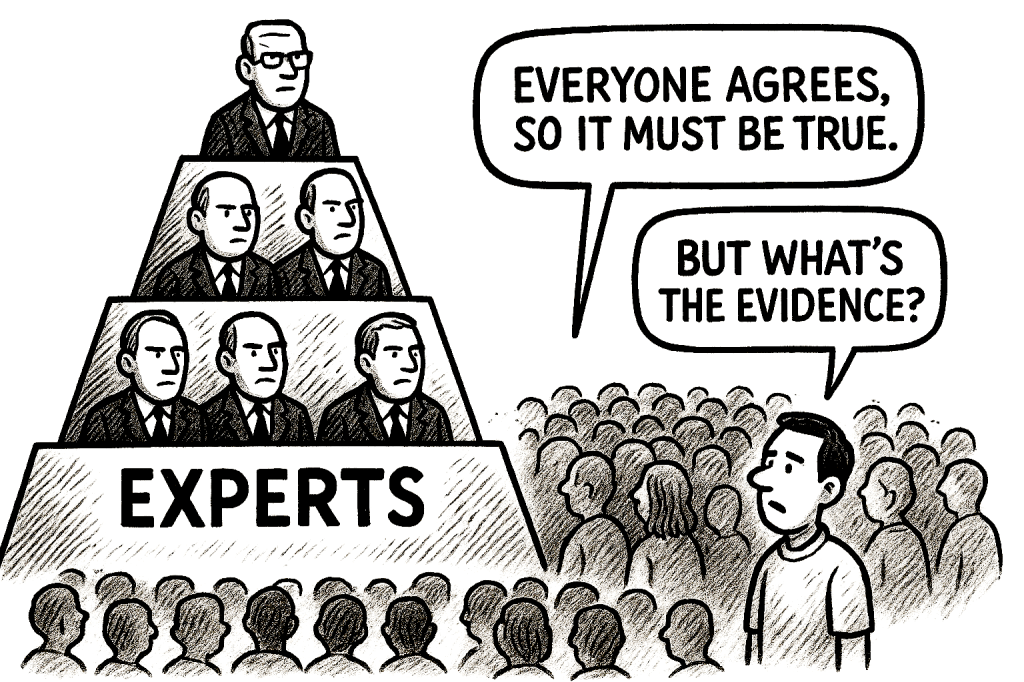

Of course, appealing to “the consensus” is not an excuse. This raises another problem in education: appeal to the authority of expertise. We saw this during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the opinions of Washington bureaucrat Dr. Anthony Fauci came to be seen as science. The man said himself that Republican lawmakers who criticize him are “criticizing science, because I represent science.” It is hard to imagine someone in authority saying something more damaging to the legitimacy of science than this. Which is why what he said next was so ironic. “If you damage science,” he said, “you are doing something very detrimental to society.”

How is criticizing Fauci’s claims or government policy based on them damaging science? What he really meant to say, I think, is that criticizing his narrative was detrimental to his authority, the basis upon which he staked his claims. But the question of the scientific veracity of a doctor’s claims rests not on his credentials or his position but on the soundness of his conclusions and the validity of the methods he used to arrive at them. Any reasonably intelligent person can independently determine whether Fauci’s claims were sound or valid, and the importance of doing so has become ever more critical in a situation where the knowledge-producing and sense-making institutions of the West have been captured by ideology and the corporate power that lurks beneath.

President Dwight Eisenhower warned Americans in his 1961 farewell address of the dangers of technocratic hijacking of science: “For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers. The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present—and is gravely to be regarded. Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific‑technological elite. It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system—ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.”

Ideology is a powerfully corrupting force in curricula and pedagogical practice. Indeed, education is, in certain areas, for the most part, no longer the pursuit of knowledge, but the practice of indoctrination. The results of a Fox News poll bear this out:

Progressives on X use this poll to portray supporters of President Trump as undereducated rubes, a typical sentiment expressed by those who think they are the betters of others. But a proper understanding of the situation finds the President’s supporters are not ignorant but relatively free from progressive programming. Indoctrination is a powerful force, and the more one is embedded in the process, with all its reinforcers, the more they reflect the programming. Noam Chomsky captures the process well in his 1983 essay “What the World is Really Like: Who Knows It—and Why”:

“There’s a vast difference in the use of force versus other techniques. But the effects are very similar, and the effects extend to the intellectual elite themselves. In fact, my guess is that you would find that the intellectual elite is the most heavily indoctrinated sector, for good reasons. It’s their role as a secular priesthood to really believe the nonsense that they put forth. Other people can repeat it, but it’s not that crucial that they really believe it. But for the intellectual elite themselves, it’s crucial that they believe it because, after all, they are the guardians of the faith. Except for a very rare person who’s an outright liar, it’s hard to be a convincing exponent of the faith unless you’ve internalized it and come to believe it.”

Trained people are products of their training. Their conditioning becomes ever more entrenched when their livelihood depends on it. As Upton Sinclair remarked after his 1934 loss in the California gubernatorial race, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”When knowledge-producing and sense-making institutions are captured by an ideology or politics, then their products—the functionaries serving elite interests—will reflect that ideology. This is not absolute, of course (I escaped it, for example), but it would be an unlikely result of indoctrination in ideologically-captured institutions for the well-trained to vote for candidates or hold positions that those institutions programmed them to reject. So, yes, there are those with advanced academic degrees who vote conservative—but to expect programming would have no effect betrays an ignorance of the force of indoctrination in ideologically-captured systems. Indeed, a deft system of indoctrination would cultivate precisely this sort of ignorance.