“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” —The First Amendment to the United States Constitution (1789)

In today’s essay, which will be my Independence Day contribution, I discuss the six rights embedded in Article One of the United States Bill of Rights (the First Amendment)—conscience, speech, press, assembly, and petition, with a sixth right, namely, association, implied. Because free speech is a cornerstone of democratic societies, and reflects the spirit of freedom that the other rights model, I focus on the free speech right primarily.

I need also to briefly discuss what the founders of the American Republic intended by advocating for a republican form of government in contrast to establishing a democracy, since it might appear as if the founders were hostile to the idea of democratic processes. Conservatives frequently make this claim, but it is not so (see America is a Republic (It is also a Democracy). Crucially, the right to free speech is a republican value and functional to democratic governance from this standpoint.

Finally, I review the illiberal opposition to freedom of speech from progressives and debunk their attempts to justify cancellation and censorship.

***

I first take up the issue of republicanism and its relationship to democracy. In Federalist No. 10, James Madison, the central figure in the framing of the United States Constitution, as well as the Bill of Rights, offers a critique of democracy, focusing particularly on the dangers of factionalism (see A Scheme to Thwart Mob Rule; also CNN Gaslights Its Viewers Over the Republican Character of the United States of America).

Madison defines faction as “a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” Madison’s primary concern is with the instability and injustices that may arise from factions.

Interpreters often use the constructs “pure democracy” and “direct democracy” to differentiate the target of Madison’s critique from the form of representative democracy republicanism entrails, where elected representatives make decisions on behalf of the people. In a pure democracy, decisions are made directly by the majority. Here, factions may emerge and oppress minority groups or pursue narrow interests at the expense of the common good. This is an inherent problem, Madison explains: “The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man; and we see them everywhere brought into different degrees of activity, according to the different circumstances of civil society.”

The argument in Federalist No. 10 is thus not a rejection of democracy per se, but rather a critique of the dangers of unchecked majority rule, or majoritarianism, rightly maligned as the “tyranny of the majority,” and recognition of the need for institutional safeguards to protect minority rights and promote the public good. The founders believed that direct democracy lacked the mechanisms for accountability and deliberation necessary for responsible governance. They argued that representative institutions provided a more deliberative process, where elected representatives, held responsible at the ballot box for their decisions, could debate issues and make decisions on behalf of the people.

Republicanism emphasizes the importance of active and engaged citizenship, civic virtue, the rule of law, and the separation of powers to safeguard against the emergence of oppressive regimes. In essence, the founders sought to establish a system of government that balanced democratic principles with mechanisms to protect individual liberties and prevent the tyranny of the majority. While they recognized the value of popular sovereignty and the consent of the governed, indeed putting these values central to national integrity, they also understood the dangers inherent in majoritarianism and thus sought to mitigate them through the principles of republicanism.

***

“If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.” Snyder v. Phelps, 562 US 443, 458 (2011)

Free speech is a cornerstone of democratic societies, allowing individuals to express their beliefs, ideas, and opinions without fear of censorship or retaliation, which means to be free from discipline, punishment, and termination for utterances protected by the right. I often describe censorship and retaliation as “costs,” then note the obvious that, if something has costs associated with it, then it isn’t free. Beyond existing as a natural right, free speech is functional, serving as a mechanism for fostering dialogue, promoting progress, and safeguarding individual liberties.

There are numerous texts on free speech. Two must-reads because of their historical importance and eloquence are John Milton’s 1644 Areopagitica and John Stuart Mill’s 1859 On Liberty. I recommend these pamphlets to everyone reading this essay. If you have read them, they are always worth revisiting. Milton argues against censorship and for the freedom of the press. He presents a powerful case for the importance of allowing diverse opinions and ideas to be expressed, even if they are controversial or unpopular. Mill argues for the importance of free expression and individual liberty. Mill posits that freedom of speech is essential for the pursuit of truth and the development of personal and societal growth. Allowing all ideas, even controversial ones, to be expressed freely allows society to discover and recognize truths. Through the clash of different opinions, even false ones, the truth will emerge more clearly. As did the founders of the American Republic, Mill was concerned about the tyranny of the majority. He warned against the tendency of democratic societies to suppress minority viewpoints through social pressure or legal means, arguing that this stifles progress and can lead to intellectual stagnation.

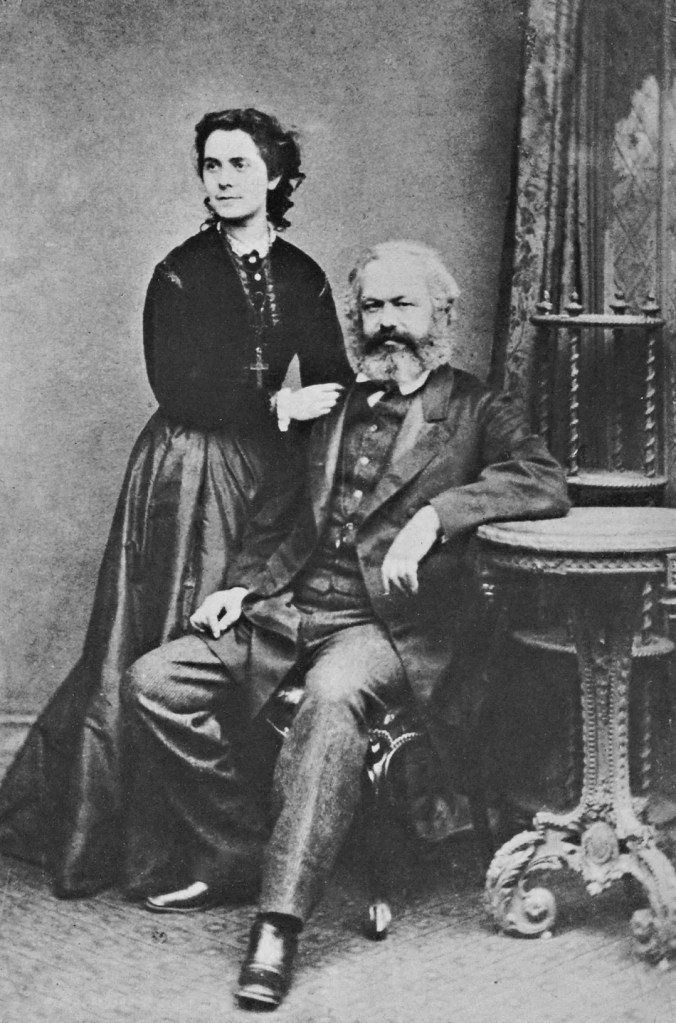

The defense of free speech is often associated with liberal thought. However, perhaps the most famous radical, socialist Karl Marx, vigorously defended the free press in the early 1840s, particularly in his articles for the Rheinische Zeitung, a Cologne newspaper for which he served as an editor. One of his most notable works on this subject is the article “On the Freedom of the Press,” published in 1842. At the time, Prussia had stringent censorship laws, which Marx vehemently opposed. His articles critiqued these laws and argued for the essential role of a free press in promoting truth and progress.

As I will argue in this essay, Marx argued that freedom of the press is a fundamental human right and a necessary condition for the development of society. He believed that the press serves as a platform for public discourse, enabling citizens to express their opinions and engage in critical debate. For Marx, the suppression of the press stifles the free exchange of ideas, which is crucial for social and political progress. He asserted that censorship is an instrument of oppression used by those in power to maintain their control and prevent the exposure of their injustices.

Marx connected freedom of the press with broader issues of human emancipation. Thus he saw the struggle for press freedom as part of the larger struggle against economic subjection and political domination. In his view, a free press empowers the oppressed by giving them a voice and facilitating their participation in the democratic process. In these essays, which deliver a full-throated commitment to the principles of equality, justice, and liberty, Marx laid the groundwork for his later critiques of capitalism and advocacy for revolutionary change.

Just as the idea and practice of republicanism can be found in ancient Greece and Rome, their examples influencing the founders of the American Republic in the development of their scheme, so can the notion of free speech be traced to those ancient civilizations. The Greek philosophers advocated for the unrestricted exchange of ideas as essential for intellectual and moral development. In democratic Athens, for instance, the concept of parrhesia, or “fearless speech,” was celebrated as a civic virtue, allowing citizens to openly criticize authority and participate in public discourse without fear of retribution.

The primary purpose of free speech, then and now, is to facilitate the free exchange of ideas and information, which is vital for the functioning of a healthy democracy. It enables individuals to express their views, challenge prevailing beliefs, and contribute to public debate. It fosters creativity, innovation, and progress by allowing diverse perspectives to be considered, weighed and measured against other each other and reality. It serves as a check on state power, ensuring accountability and transparency in the exercise of juridical, military, and political authority. Free speech is thus essential to self-government and societal progress.

The concept of free speech is not absolute; it comes with reasonable limitations. However, any limitations must be inherent, which is to say that any imposition must facilitate and enlarge the intrinsic purpose of free thought and expression. Crucially, then, understanding restrictions on speech as limitations can be misleading. The matter is better put this way: the curtailment of certain speech-like acts are welcome when they serve to expand and deepen the essential character and purpose of the right. These curtailments concern speech that directly incites violence (“true threats”), harasses (repeated, unwelcome, and unavoidable utterances that annoy, degrade, or intimidate), disrupts (the “hecklers veto”), and utterances that cause reputational damage by making knowingly false claims about a person. i.e., defamation in the forms of libel and slander. Speech is also constrained by time and place restrictions, as well as relevance.

I take up the last curtailment first. Suppose a classroom where students are talking to one another about something unrelated to the topic at hand. They may be quieted or asked to leave the room without violating their First Amendment rights. Their free speech right is not being constrained by their speech-like acts being restricted; indeed, their speech-like acts are interfering with the free speech rights of the teacher and other students who have a right to not only impart but also to receive information, knowledge, and opinion. Utterances made in a lecture or in discussion that are not germane to the subject matter or purpose of the activity are not only justifiably disallowed but must be restricted if free speech is to be manifest in this situation. The association of the students is nor harmed by having them leave the room. They are free to continue their association at some other location.

Related to time and place restriction is speech-like acts used to suppress the free speech rights of others, or the “heckler’s veto.” The heckler’s veto describes a situation where an individual or individuals use noisemaking devices, obstructions, or speech-like utterances to disrupt speech and its reception. Although the appropriate response by authorities would be to ask the heckler to leave, and even forcibly remove him if he refuses, authorities often violate the speech of speaker and audience by limiting or suppressing speech due to hostile reactions or in anticipation of such reactions by a group of dissenters. This problem often arises in the context of protests or controversial speakers on college campuses. Administrators will cancel or restrict events out of concern for potential disruptions or violence from protesters. This is often referred to as “deplatforming” or “disinviting” speakers. Courts have ruled on the matter (see, e.g., the 2015 Sixth Circuit ruling in Bible Believers v Wayne County), but officials continue to violate the rights of speakers and their audiences.

The heckler’s veto poses a false dilemma for free speech principles, as under cover of maintaining order and security, authorities use the action or threat to justify the suppression of speech ostensibly not for its content or message, but because of the reaction it may provoke from others. Any restrictions on speech meant to prevent imminent violence or protect public safety must be narrowly tailored and content neutral. The heckler’s veto thus gives veto power to those who seek to silence opposing viewpoints through disruption and intimidation—if the authority legitimizes the action by canceling the event.

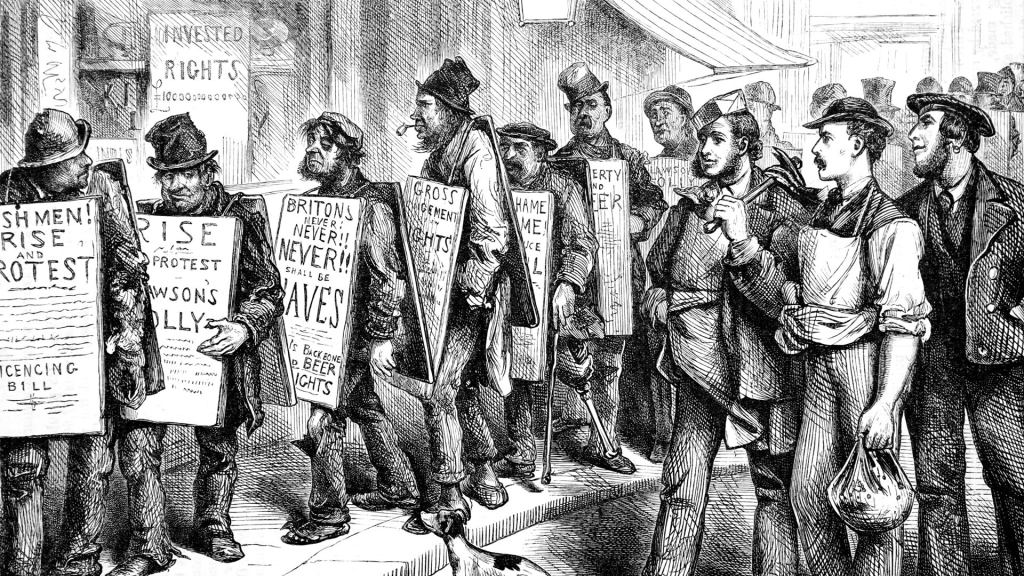

Progressives argue that the heckler’s veto is an act of civil disobedience, cloaking it as “counter-speech,” and therefore a form of expressive conduct that should be protected by the principles of free speech and assembly. While civil disobedience is a form of political expression, individuals engaged in such action are intentionally breaking laws or rules as a means of advocating for social change or protesting against perceived injustices. Put another way, advocates of such action argue that, while civil disobedience involves actions that may be illegal, it is First Amendment principle.

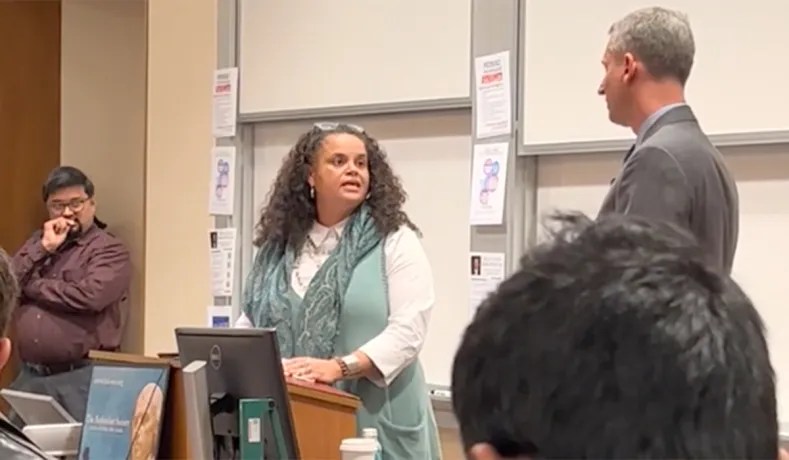

As notable example can be seen as an act of civil disobedience and thus protected as counter-speech occurred at Stanford Law School (see FIRE’s “Stanford Law hecklers demanding ‘free speech’ don’t know what they’re asking for”). In March 2023, during a Federalist Society event featuring Fifth Circuit Judge Kyle Duncan, students shouted down and disrupted his speech, claiming his views were too harmful to be aired. The protesters wore masks with the slogan “counter-speech is free speech,” arguing that their disruptive actions were a form of expressive conduct protected under free speech principles. At the heart of the student protect was Duncan’s ruling denying a transgender prisoner’s request to have his pronouns changed in 2020. Tirien Steinbach, associate dean for diversity, equity, and inclusion, took the student’s side, accusing Judge Duncan of causing “harm.”

These acts of effective cancelling are often framed as “accountability.” An example of accountability in the press world, which also involved transgender issues, is found in the case of Ryan Anderson’s book When Harry Became Sally. In February 2021, Amazon removed the book from its platform without prior notice or explanation. Amazon framed the decision to remove the book an act of accountability, arguing that the content of the book violated Amazon’s policies regarding hate speech and offensive content. (See Francis Menton’s essay in the Manhattan Contrarian, “Audacious Deplatforming: Some New Examples” for more examples.) Another example involves the deplatforming of former President Donald Trump from multiple social media platforms following the January 6th Capitol riot (I discuss this in my last essay Three Big Lies About Trump—and Promising Developments in the Transatlantic Space). Social media companies such as Twitter and Facebook justified their actions by claiming they were holding Trump accountable for inciting violence and spreading misinformation. These companies argued that their decision was a necessary measure to prevent further harm and protect the integrity of their platforms.

Free speech refers to the lawful right to express oneself without interference or censorship from the government or other authorities. Dean Steinbach, acting in her official capacity, violated Judge Duncan’s First Amendment rights—as well as the rights of the students in attendance to hear his words. So did Amazon and social media companies in principle violate the free speech rights of Anderson and Trump respectively. Cancel culture is not about accountability. Holding somebody accountable for something they did requires that their actions was covered by some law or rule prohibiting or restricting those actions. Those giving opinions are not engaged in action subject to accountability. (See Accountability Culture is Cancel Culture: Double Think and Newspeak in Today’s America.)

Progressives make arguments regarding the potential harms that certain types of speech can cause. For example, free speech opponents argue that allowing free speech leads to the proliferation of “hate speech,” which can marginalize and oppress certain groups based on characteristics such as gender, race, religion, or sexual orientation. We see this occurring frequently on college campuses. Activists have frequently sought to prevent speakers with openly racist or anti-LGBTQ views from giving talks, arguing that such speech perpetuates stereotypes and hatred against marginalized communities. This stance is rooted in the belief that allowing such speech can create a hostile environment for students and staff belonging to these groups. For instance, at the University of California, Berkeley, controversial figures Milo Yiannopoulos and Ann Coulter faced significant opposition from students and community members who argued that their rhetoric constituted hate speech. In both cases, both examples of the “heckler’s veto,” concerns about potential violence led to the cancellation of their events.

These actions were framed by supporters as measures of accountability, aiming to protect the campus community from the harmful impacts of hate speech. However, in Matal v Tam (2017), the Supreme Court unanimously affirmed that there is no “hate speech” exception to the First Amendment. The US government may not discriminate against speech on the basis of the speaker’s viewpoint. What constitutes the US government? Crucially, the incorporation of the First Amendment into all public settings has been a significant aspect of constitutional law in the United States. This process began with the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, which extends the protections of the Bill of Rights to include actions by state governments. Through a series of Supreme Court decisions, the principles of the First Amendment have been applied to state and local governments, ensuring that these rights are protected not only at the federal level but also in all public settings across the nation.

In Gitlow v New York (1925), the Supreme Court held that the freedoms of speech and press are fundamental personal rights and liberties protected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from impairment by the states. This case set a precedent for the incorporation doctrine, allowing for the application of First Amendment rights to the states. Another significant case was Near v Minnesota (1931), where the Court struck down a state law that allowed prior restraint on publications, reinforcing the idea that the freedom of the press is protected against state infringement. The incorporation of the First Amendment has been further expanded through cases like Mapp v Ohio (1961), which, although primarily about the Fourth Amendment, helped solidify the doctrine that states must adhere to the Bill of Rights. Additionally, cases like Tinker v Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) extended First Amendment protections to public school settings, recognizing students’ rights to free speech, provided it does not disrupt the educational process. These legal precedents ensure that freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and petition are upheld in all public settings, fostering a broad and robust protection of civil liberties across the United States. (See my essay My Right to My Views is Your Right to Yours).

Progressives contend that hate speech contributes to social division, discrimination, and even violence against marginalized communities. More broadly, the argument is that false information, propaganda, or speech that incites violence, directly harm individuals or society as a whole. They suggest that limiting speech is necessary to protect people from harm and maintain social order. In the case of propaganda and speech that incites violence, what constitutes a “true threat,” courts have acknowledged that this is among the justifications for limiting utterances. A “true threat” refers to a statement or communication that conveys a serious intention to harm someone or something. It’s not just an expression of anger or frustration, but rather a statement that reasonably makes the recipient fear for her safety or well-being. True threats can take various forms, including verbal threats, written messages, gestures, or other actions that communicate an intent to cause harm. In legal contexts, determining whether a statement constitutes a true threat often involves considering the context, the intent of the speaker, and the reasonable interpretation by the recipient.

At the same time, appeals to incitement can be abused. The notion of harmful speech is subjective and can vary widely depending on cultural, political, and social contexts. Implementing restrictions on speech based on potential harm involving subjective judgments about what constitutes harm or the potential harm in question represents a slippery slope. This is why it is generally better to address harmful speech through (actual) counter-speech, education, and the fostering of social norms rather than through legal restrictions, which can have unintended consequences for freedom of expression. For example, the antisemitic sentiment rampant today on college campuses should not result in the targeting and punishment of antisemitic speakers, rather it should be addressed by counter-speech and the fostering of social norms that condemn antisemitism and the ideologies that promote it.

Indeed, while hate speech may be deeply hurtful and offensive, allowing it to be expressed can actually be beneficial in the long term. Permitting hateful ideas to be aired publicly provides an opportunity for them to be challenged and countered. It serves as a barometer for societal attitudes, highlighting areas where more education and understanding are needed. Moreover, restricting hate speech runs the risk of empowering authorities to censor any speech they deem offensive, which can be abused to suppress legitimate dissent. The question to be asked here is who will be the commissar? Who would you have over you telling you what you can and cannot say? Censorship also has the unintended effect of amplifying the speech in question, as resistance to its suppression can be represented as suppression of dissent.

The problem of subjectivity looms large in the hate speech debate. What’s perceived as hateful can vary based on personal viewpoints and cultural contexts—that is, it is observer- and context-dependent. What one person perceives as hateful, another might view as legitimate criticism or even as an expression of their own beliefs or identity. For example, a statement criticizing a particular religious belief—and I have made many of these in my writings—might be perceived as hate speech by some adherents of that religion while seen as protected speech or legitimate discourse by others. Hate speech is defined within a specific cultural and social context. Moreover, societal norms and values evolve over time, leading to changes in what is considered acceptable speech and what is deemed hateful. Expressions described as hateful sometimes stem from a sense of group identity and solidarity rather than malicious intent.

It is the same thing with so-called “offensive speech,” that is the act of restricting or prohibiting expressions that are deemed offensive or socially unacceptable (see See Offense-Taking: A Method of Social Control). This can take various forms, from legal regulations to self-censorship. Advocates of censoring offensive speech often argue that it’s necessary to protect individuals and groups from harm, maintain public order, and promote social cohesion. Consider again my record of irreligious speech. I have written a lot on the problem of Islam, and in so doing I have shared depictions of Muhammad that, according to the aniconism of Islamic doctrine, constitute blasphemy. But I am not a Muslim; therefore I am not obliged to follow the rules of that faith. More that this, I am permitted to use offensive imagery to make my point more effectively. Indeed, offensive-taking is often the first step towards enlightenment. This is why free speech advocates argue that censorship stifles open dialogue, impedes the exchange of ideas, and restrict individuals’ rights to express themselves freely. Giving authorities the power to determine what is considered offensive leads to censorship being used to suppress dissenting voices or unpopular opinions. I cannot effectively oppose dangerous ideologies like Islam if I am forbidden to offend their devotees.

Advocates for restricting free speech argue that certain groups, such as children or minority group members, have less power in society and thus need protection from potentially harmful or offensive speech. Limiting certain types of speech, they argue, is necessary to safeguard the rights and well-being of these vulnerable groups. Since I have argued for limiting materials available to children in public settings, I want to clarify my position on the matter. While it’s essential to protect vulnerable individuals from discrimination and harm, I have long argued that censoring speech may not the most effective way to achieve this. Instead, fostering an environment of open dialogue and debate can empower marginalized communities to challenge oppressive ideas and advocate for their rights. Restricting speech in the name of protecting vulnerable groups can have a chilling effect on all speech, stifling important discussions and hindering progress.

One obvious problem with calls to limit speech to protect vulnerable persons is the matter of who counts as a vulnerable person. This is very often a subjective matter. There are many instances of predatory groups claiming to be the vulnerable ones manufacture statuses and use the rhetoric of vulnerability and victimhood as a ruse to secure privileges and to access spaces safeguarding truly vulnerable individuals, what is sometimes referred to as “emotional blackmail.” (See The False Doctrine of “Weapons of the Weak”; Speech Acts as “Systemically Harmful”: More on the “Weapons of the Weak”.)

For example, girls and women require safe spaces given the drastic overrepresentation of males in the perpetration of sexual and other crimes against females. More than three-quarters of all violent crime offenders are male, with males accounting for a significant majority of violent crimes, including homicides, assaults, and robberies. When it comes to sexual offenses, the disparity is even more pronounced. According to data from the US Sentencing Commission, around 98 percent of sexual abuse offenders are male. This includes a wide range of sexual offenses, such as rape, sexual assault, and other forms of sexual violence. Trans identifying males claim vulnerability as a strategy for accessing spaces reserved for girls and women (bathrooms, crisis centers, hospital rooms, locker rooms, prisons). We also see the mainstreaming of male access to the vulnerable with the term “minority attracted person,” a term designed to rebrand pedophiles as a legitimate identity and depicted as a vulnerable group.

At the same time, when restricting speech is sought in the case of public school curriculum and spaces exposing children to age-inappropriate, often pornographic materials, opponents of free speech will decry such restrictions as unreasonable limitations on speech, misdescribing child safeguarding as “book banning,” etc. (See Defending Public Education from the Self-Righteous Martyr; Whose Spaces Are These Anyway? Political Advocacy in Public Schools; Civic Spaces and the Illiberal Desire to Subvert Them; Ideology in Public Schools—What Can We Do About It?; The LGBTQ Lobby Sues Florida; Seeing and Admitting Grooming; What is Grooming?; Kids Resisting Indoctrination.)

A variation on the vulnerable group or individual argument is the claim that exposure to certain types of speech, such as graphic violence or explicit content, can cause psychological harm, particularly to vulnerable individuals such as children or trauma survivors. Opponents of free speech advocate for restrictions on such utterances to protect emotional and mental wellbeing. If you remind them of the childhood rhyme about “sticks and stones,” they will indicate the body of scholarly literature showing that speech can harm a person psychologically. (See Reinforcing the Point of the Exercise: The Function of Safe Spaces.)

While certain types of speech may indeed cause emotional and psychological distress, and children should be protected from bullying and indoctrination, censorship is not always the most effective way to address this harm. Individuals should be empowered to make their own choices about what speech they consume and how they engage with it. Censoring speech based on its potential to cause psychological harm sets a dangerous precedent for limiting freedom of expression based on subjective criteria.

The argument that certain forms of speech, such as extremist rhetoric, hate speech, offensive imagery undermines social cohesion and threatens the stability of democratic societies is one of the more concerning rationalizations for controlling thought. This form of advocacy for restrictions on speech proceeds by citing the necessity of promoting tolerance, respect, and unity among diverse groups. While promoting social cohesion is a worthy goal, censoring speech in the name of unity is counterproductive. True cohesion is built on a foundation of empathy, mutual respect, and understanding, which cannot be legislated or policed. These goals must be achieved through open dialogue and the free exchange of ideas. Restricting speech, particularly dissenting or controversial speech, undermines the democratic principles of freedom of expression and pluralism, which are essential for a healthy and vibrant society.

One of the most serious dangers to free speech that has emerged is the control over so-called misinformation and disinformation (see The Deep State and Cognitive and Emotional Manipulation; Twitter Interfered in the 2020 Election; Refining the Art and Science of Propaganda in an Era of Popular Doubt and Questioning; Cognitive Autonomy and Our Freedom from Institutionalized Reflex). It’s not that such things don’t exist. Misinformation is false or inaccurate information spread unintentionally, often due to misunderstanding or lack of verification. Examples include bad statistics, urban legends, etc. Misinformation is everywhere. Indeed, Christianity and Islam feed their billions of devotees a steady diet of misinformation. They even hold that believing the misinformation is a noble act of faith. Disinformation is deliberately spread with malicious intent to deceive or manipulate. It includes fake news, hoaxes, and propaganda. Religion is also a source of disinformation.

To be sure, both misinformation and disinformation can damage trust, influence political decisions, and polarize communities. However, the defense of citizens’ rights to spread misinformation and disinformation is also protected by principles of free speech and freedom of expression. Moreover, the determination of what constitutes misinformation and disinformation can be subjective and dependent on one’s beliefs, cultural context, and perspective. What some people may consider factual information, others may view as false or misleading. For instance, beliefs held within religious contexts may be considered sacred and true by adherents but could be seen as misinformation by those who do not share those beliefs. Similarly, fringe beliefs like flat earth theory may be dismissed by the majority as misinformation, but individuals who subscribe to these beliefs may view them as legitimate interpretations of reality.

These complexities underscore the challenge in addressing misinformation and disinformation in a diverse and pluralistic society. In theory, we are told, it requires striking a balance between respecting individuals’ rights to hold and express diverse viewpoints, including those that may be considered fringe or controversial, while also promoting critical thinking, fact-checking, and the distribution of accurate information. In practice, this often becomes arbitrary and dependent on who controls the distribution of information—back to the problem of the commissar. In democratic societies, protecting freedom of expression and religious liberty while also combating harmful misinformation involves fostering an environment where diverse perspectives can coexist while promoting education and media literacy to help individuals discern between credible and false information. However, limiting individuals’ ability to spread false information can set a dangerous precedent for censorship and infringe upon basic freedoms.

Finally, critics of unrestricted free speech argue that it often benefits those in positions of power and privilege, allowing them to maintain their dominance. They contend that laws and norms surrounding free speech reflect and perpetuate existing power structures, allowing dominant groups to maintain control and silence dissenting voices. They contend that restrictions on speech can help to balance power dynamics and promote greater equality and social justice. Scholars within critical legal studies, critical race theory, feminist studies, queer theory, etc., have generated a plethora of opinions on how free speech reinforces inequalities and harm marginalized groups (see, e.g, Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Duncan Kennedy, Catharine MacKinnon, and Roberto Unger). They suggest that restrictions on speech may be necessary to promote social justice by preventing the misuse of speech to oppress or discriminate against vulnerable populations. Even the stalwart liberal John Stuart Mill, in articulating the “harm principle,” argued that individual liberty is justifiably limited to prevent harm to others, implying that speech that directly incites violence or causes significant harm may warrant restriction.

While it is true that powerful individuals and groups may benefit from unrestricted free speech, censorship is not the solution to addressing power imbalances. Censorship reinforces existing power structures by silencing dissenting voices and limiting the ability of marginalized groups to challenge authority. True equality and justice are better served by promoting a marketplace of ideas where diverse perspectives can be heard and debated freely. Indeed, the argument against censorship as a solution to power imbalances centers the irony of reinforcing existing power structures in censorship. Censorship gives those in authority or privilege the ability to determine what is acceptable speech, potentially silencing dissent and limiting marginalized groups’ ability to challenge the status quo. Thus there is a paradox in using censorship to address power imbalances: those advocating for censorship are themselves seeking to exert a form of power by controlling the freedom of expression of others. This brings to mind the paradox that moved Christopher Hitchens to warn the opponents of free speech about making a rod for their own backs.

* * *

In examining the foundational principles of the United States as a republic and the founders’ intentions in advocating for such a system over direct democracy, it becomes evident that their concerns centered around the dangers of unchecked majority rule and the potential for factions to undermine the rights of individuals and the common good. Through the lens of James Madison’s Federalist No. 10, the critique of “pure democracy” highlights the need for institutional safeguards to protect minority rights and promote responsible governance. Republicanism, with its emphasis on active citizenship, civic virtue, and the separation of powers, offers a framework for balancing democratic ideals with mechanisms to safeguard individual liberties. Central to this balance is the protection of free speech, a fundamental right essential for ensuring governmental accountability, fostering dialogue, and promoting progress. While free speech is not without limitations, particularly in cases of speech that incites violence or harasses individuals, the broader goal is to facilitate the free exchange of ideas and information vital for a healthy democracy. The principles of republicanism, democracy, and free speech are intertwined, forming the foundation of a vibrant and truly inclusive society. By upholding these principles, we can strive towards a world where diverse perspectives are respected and the voices of all individuals are heard.

Before leaving this essay, I must mention the problem of free speech for corporations and articulate a caveat to the things I have said here. This clarification is necessary given the recognition by courts that corporations are in some senses legal persons. I disagree with the history of decisions and legislation conferring this status on business entities, but I live in a world in which this status has been conferred, whether finally who knows. However, it is flesh-and-blood individuals who possess inherent rights to free speech, which are considered fundamental to personal autonomy and democratic participation. These rights enable individuals to express themselves, engage in public discourse, criticize authority, advocate for social change, and share their unique perspectives and beliefs.

Corporations, on the other hand, are legal entities created by law for conducting business activities. While they enjoy certain legal rights and protections, such as contract and property rights, these are not inherent or natural in the way human rights are. The primary purpose of corporations is commercial activities and profit-making rather than the exchange of ideas or democratic participation. Granting corporations the same free speech rights as individuals leads to undue influence of corporate power in public discourse and democratic processes. Treating corporations as persons in the context of free speech distorts the original intent of free speech protections, which were designed to safeguard individual liberties and promote democratic ideals—the rights and purposes of concrete flesh-and-blood persons.

Nonetheless, courts have granted corporations free speech rights. One of the earliest significant cases addressing corporate speech was First National Bank of Boston v Bellotti (1978), in which the Supreme Court, Justice Lewis Powell writing the majority opinion, struck down (5-4) a Massachusetts law that prohibited corporations from spending money to influence the outcome of ballot initiatives. Powell reasoned that the value of speech does not depend on the identity of the speaker and that the public has a right to receive information and ideas from diverse sources, including corporations. Another case is Pacific Gas & Electric Co. v Public Utilities Commission of California (1986), wherein the Court ruled (5-3) that forcing a corporation to include speech with which it disagreed violated the First Amendment, emphasizing that freedom of speech includes both the right to speak and the right not to speak.

Perhaps the most notorious case is Citizens United v Federal Election Commission (2010), where the Court ruled (5-4) that the government cannot restrict independent expenditures for political communications by corporations, associations, or labor unions. This decision invalidated parts of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) that had prohibited such expenditures. The Court, in a majority opinion written by Justice Anthony Kennedy penned the majority opinion, emphasizing that political speech is indispensable to a democracy, which is no less true because the speech comes from a corporation. (I recently commented on this case in When Progressives Embrace Corporate Speech.)

Equating corporate speech with individual speech undermines efforts to regulate corporate influence in media, politics, and other spheres of public life. Additionally, being that corporations are artificial entities created for economic purposes, they cannot possess the same moral agency or human interests as people and should not be afforded the same rights and privileges. Therefore, the protections afforded by the First Amendment only apply to corporate expressions on a case-by-case basis in light of the principles articulated in this essay. In the long haul, however, humanity must endeavor to strip from this artificial person the rights and privileges of real persons. That the rulings made in the major cases cited above are close, there is reason to hope that we might in the end remove from corporations a right that should inhere only in flesh-and-blood persons. Heaven help us if the reverse of this is ever set down in precedent.

I am always reminded by this situation of the eighteenth century British lawyer and politician Baron Thurlow’s words, paraphrased in various forms, but essentially something to this effect: “Did you ever expect a corporation to have a conscience, when it has no soul to be damned, and no body to be kicked?” I read this as a statement concerning the difficulty in countering the speech of such a powerful entity as a corporation, which today is entangled with the state such that the latter, in doing the bidding of the former, can, as the Supreme Court just effectively held, by tossing out (in a 6-3 decision) a lawsuit (Murthy v Missouri et al.) that sought to restrict the federal government’s ability to communicate with social media companies (Google, Meta, and Twitter) about content moderation over what it saw as “misinformation,” instruct these quasi-private entities to censor information on vaccines efficacy and safety and election interference.

* * *

Note about intimidation and harassment:

Intimidation often falls under the broader umbrella of harassment, especially if it involves repeated or persistent actions that cause discomfort, distress, or fear. The intent behind the speech and its impact on the target are crucial in determining whether it constitutes intimidation; also context (it is in the workplace or in a public forum, and so on). Harassment can include verbal threats, stalking, or other behaviors intended to intimidate. If intimidation involves threats of violence or other harm, it may be treated as a criminal offense. Threats are usually not protected under free speech because they can cause immediate fear and have the potential to lead to violence. In schools or workplaces, intimidation can be categorized as bullying. Policies and laws often address bullying separately, with specific measures in place to prevent and respond to it.

While intimidation can be linked to harassment and may intersect with free speech issues, it is typically treated under specific legal frameworks that address threats and bullying. The exact categorization and handling of intimidation depend on the nature of the actions and the relevant laws and policies in the jurisdiction.