I am not the first person to address this subject. Most famously, Karl Popper, in his 1945 book The Open Society and Its Enemies, argued that a tolerant society cannot afford unlimited tolerance. If a society tolerates the intolerant without limit, those intolerant forces can destroy tolerance itself. On this basis, Popper contended that a tolerant society has the right—and even the duty—to be intolerant of intolerance, especially when it threatens democratic institutions or the rights of others. He was concerned with totalitarian ideologies in general, but the context of his writing was heavily shaped by both fascism and communism. His point is not to suppress dissent lightly, but to protect the framework that allows open debate and freedom from being overrun by forces that would abolish them. A critic might say that Popper’s argument is a paradox. But is it?

I addressed Popper’s apparent paradox in late February of this year in Weaponizing Free Speech or Weaponizing Speech Codes? (See also my February 2021 essay The Noisy and Destructive Children of Herbert Marcuse and my August 2019 Project Censored article Defending the Digital Commons: A Left-Libertarian Critique of Speech and Censorship in the Virtual Public Square.) What prompted that essay on Popper was Vice President JD Vance’s speech at the Munich Security Conference, criticizing European nations for their restrictions on free speech and association. There, I concerned myself with the suppression of populist nationalist parties in Germany and the larger problem of censorship in Europe.

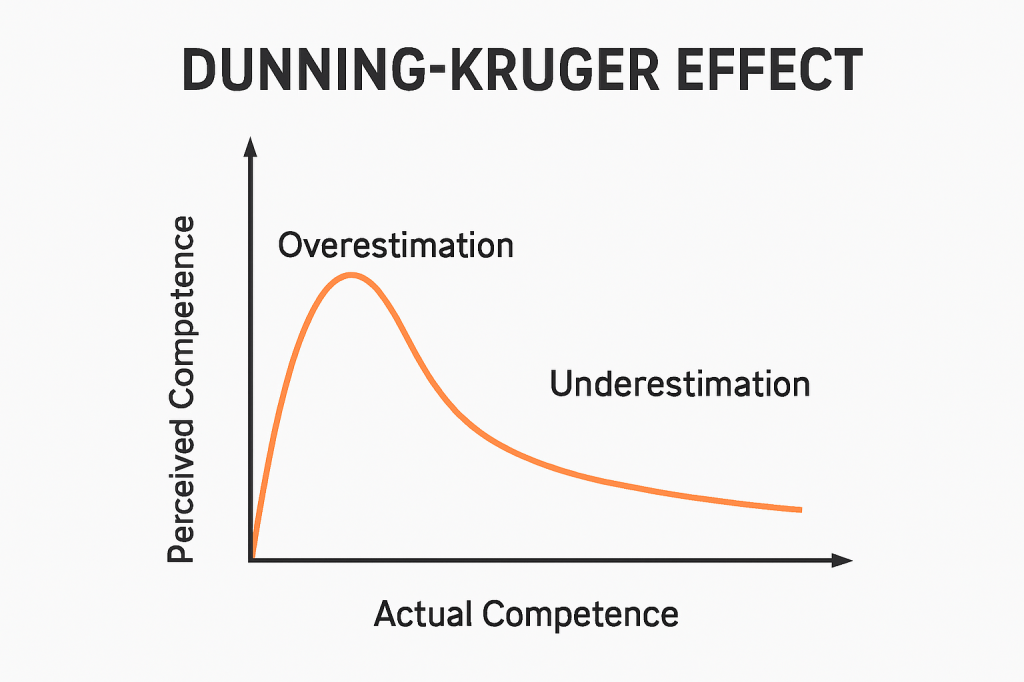

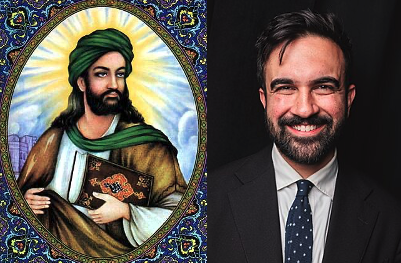

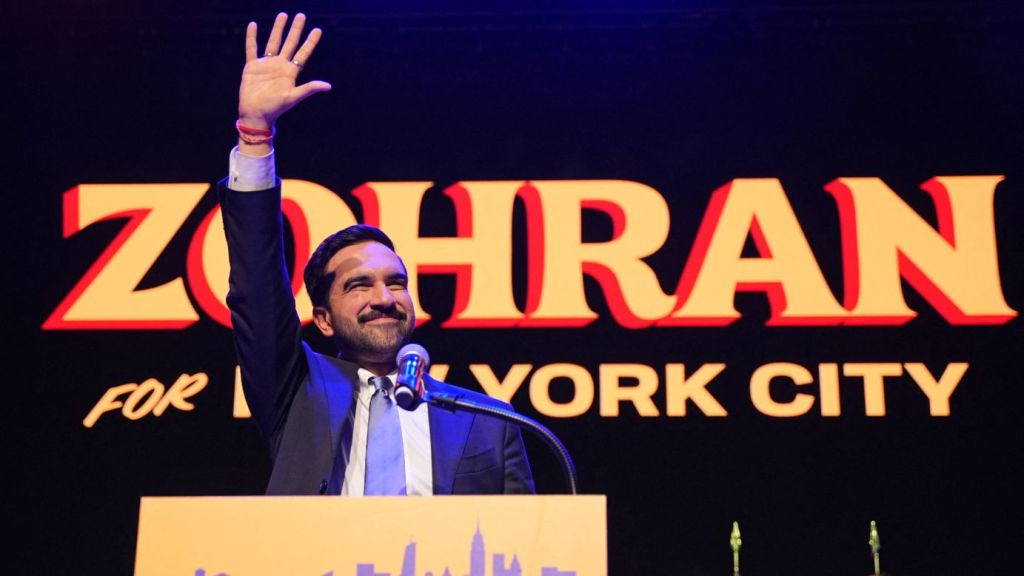

In the present essay, which follows up on one of Sunday’s essays (Defensive Intolerance: Confronting the Existential Threat of Enlightenment’s Antithesis), I turn my attention to the ascension of Muslims to political office in the West, most obviously the victory of Zohran Mamdani in New York City’s mayoral race (which parallels the election of Sadiq Khan as mayor of London in 2016). I am drawn back into this subject not only because of this development but also because of a video I recently watched, which I posted on X on Friday (see below). Ayann Hirsi Ali makes a strong argument concerning the tolerance of intolerance and how failing to keep democracy safe from totalitarian actors is a form of what Gad Saad, a professor at the John Molson School of Business at Concordia University in Canada, calls “suicidal empathy.”

Suppose a society values religious tolerance and guarantees every individual the freedom to follow their own faith. We don’t have to suppose this, of course, since this is the situation in the United States with the First Amendment in our Bill of Rights—at least in our finer moments. Yet, even in the light of the power of that Article, a question arises when a religious (or other ideological) group that rejects pluralism seeks political power. On the surface, barring such a group from governing might seem to contradict the principle of religious freedom. How can a tolerant society justify restricting a religion (or ideology) when it claims to respect the right of all individuals to believe as they choose?

Following from this, those who call for restricting a religion based on its rejection of religious pluralism are often accused of religious intolerance and smeared as bigots. But are they? Religious pluralism distinguishes between private belief and the political or personal capacity to impose that belief on others. Surely that distinction matters. Under the terms of religious tolerance, each person remains free to worship, practice, and organize according to their faith, provided they respect the same rights for others. No religion may demand that others obey its doctrines or attempt to enforce its rules across society. However, obtaining the political—or claiming the personal—capacity to impose beliefs on others, in this case Islam, a totalitarian project that either subjugates non-Muslims or kills them (I will leave to decide which is worse), is something quite apart from religious liberty. More accurately, the problem is the negation of religious liberty.

By separating personal faith from political authority, the free society ensures that belief itself is never suppressed while preventing coercion or domination by some over others. At the same time, it must preserve that arrangement by ensuring that religious groups seeking to undermine it are barred from political power. I would argue, if we agreed that this were necessary, that this restriction cannot rely on a guarantee from that group that they will respect pluralism if they obtain power; it must be based on an understanding of the doctrine of the religion itself. If the doctrine leaves no room for pluralism, then adherents of that doctrine are disqualified from holding office. The adherents cannot be trusted because the doctrine that moves them is totalitarian.

To put this another way, when a religious group explicitly rejects pluralism and seeks to impose its will on others, the society may justifiably limit its political power. This may include barring it from governing, enforcing laws, or controlling institutions in ways that would undermine religious freedom. The restriction is not on private belief, but on acquiring the capacity to destroy tolerance itself. In this way, the society preserves both freedom and pluralism: individuals can freely follow their religion, while no religion is allowed to use that freedom to eliminate the freedom of others. Nothing is taken from the person except his access to the means to take away the religious liberty of others.

The First Amendment is not the only obstacle in defending tolerance from subversion by the intolerant. By explicitly prohibiting any religious test for public office, a principle articulated in Article VI, Clause 3, which declares that “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States,” the US Constitution makes it more difficult keeping from office members of a totalitarian political movement that moves under the cover or religion. Indeed, this is arguably the most daunting obstacle since it concerns the specific political right we are discussing. The Constitution does place qualifications on those seeking office, including age restrictions, and the requirement that any candidate running for President of the United States must be a natural-born citizen. But it appears to disallow any restriction on the basis of religious affiliation.

This provision, remarkable in 1787, when most nations and even many American colonies imposed religious requirements on public officials, often restricting officeholding to Protestants, could not have anticipated the Islamization project. Indeed, it was beyond their imagination to envision Muslims as potential officeholders. What concerned them was the policing of Christian sects or deism, which was relatively common among educated elites, including some of the Founders. Many of the colonial-era religious tests and oaths were explicitly or implicitly designed to exclude Catholics from holding public office or exercising full civil rights. By rejecting such tests, the framers established that the federal government would be secular in character, open to individuals of any or no faith.

Later interpretation and the Fourteenth Amendment extended this protection to state and local offices as well. While voters remain free to consider a candidate’s religion in their private judgment, the government itself cannot impose or enforce religious qualifications. However, religious tests remained on the books for several decades in several states, namely those that required affirmation of a Supreme Being. The Supreme Court only struck these down in 1961, in Torcaso v Watkins, ruling that states could not require a declaration of belief in God as a condition for public office. Beyond religion, certain federal and state oaths required officials and teachers to swear they were not members of the Communist Party or any “subversive organization.” These loyalty oaths were also gradually struck down as violations of free speech and associational rights (e.g., Keyishian v Board of Regents, 1967).

Together with the First Amendment’s guarantees of religious liberty and the prohibition of an established religion, the no religious test clause forms a cornerstone of America’s commitment to freedom of conscience and the separation of church and state. However, today we confront a totalitarian movement that uses foundational law to establish a political-religious regime that perverts that foundation. This is not an abstract concern. As I write these words, this is happening across the world.

Today, there are around fifty Muslim-majority countries. Fewer than half of these countries are formally secular, that is, arrangements separating religion from government or law. The rest are governed in whole or in part by Sharia. Indeed, even in the formally secular Muslim-majority state, the secular arrangement is more nominal than substantive. Moreover, apart from government oppression, those who do not subscribe to Islam must deal with the extra-legal actions of Muslim proselytizers.

Muslims are now colonizing the West. Before 1970, in the United States, there were fewer than 250,000 Muslims. Today, the number is approaching 3.5 million, concentrated in major Blue Cities in the Midwest and Northeast United States. In Europe, the number is projected to reach 9 percent of the population by 2030. Muslim representation is already greater than 8 percent in France and Sweden.

What is driving this growth? Immigration (especially post‑1960s), higher fertility among Muslim immigrant populations, and a younger age structure. However, the proportion of Muslims need not be large to shift politics. Islam, which already enjoys the support of European elites, joins with progressive and social democratic forces, to multiply its power—what is known as the Red-Green Alliance. The Muslim population in New York City is today around 10 percent of the city’s population, or roughly 850,000. A Muslim was just elected mayor of that city. In Greater London, approximately 15 percent of the population identifies as Muslim. A Muslim was elected mayor of that city in 2016 and is still serving. The effect of this, as well as in other European countries and Canada, is the spread of Sharia councils and tribunals. Populations in the West are already partially governed by Sharia. (See Whose Time Has Come?)

The question of whether the West should allow the Islamization of its countries is an either/or proposition. There is no neutral position one may take on the question. Jihadism, the politics to sow the seeds of Islam everywhere, is a militant doctrine advocating the establishment of Islamic-style governance through violent action. The Ummah is a central concept in Islam that refers to the global community of Muslims—those who share a common faith in Allah and follow the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad. The term literally means “community” or “nation.” But it carries a deeper moral, religious, and social meaning that transcends ethnicity, geography, or political boundaries. In its most profound sense, the Ummah is the collective body of believers united by their submission (islām) to God. The Qur’an uses the term to describe not just a sociological grouping but a divinely guided community.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Muslim intellectuals revived the concept of the Ummah as a rallying cry for unity among Muslims across colonial and cultural divides. Pan-Islamism seeks to reawaken a sense of shared religious and civilizational identity that transcended ethnic and territorial boundaries. The goal is to reestablish and spread across the world the Caliphate, the Islamic system of governance that represent the unity and leadership of the Ummah under a single ruler known as the Caliph, or khalīfah rasūl Allāh, meaning “successor to the Messenger of God.” For jihadists, the Ummah is not merely a theological concept but a political ideal—a means to unify the Muslim world and spread Islam globally.

In this respect, Islamism is like fascism, seeking to subject every man, woman, and child under totalitarian control. More than similar: Islam is a species of the thing itself. Islam is a clerical fascist project. Either one condemns fascism in whatever form it takes or he supports it, even if the latter comes with disinterest or silence. One cannot be neutral on the matter.

In my earlier treatment of Popper, the issue at hand was censorship of offensive ideas in Europe, not the question of political office. However, there have been steps by Germany to challenge the status of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) under its laws for protecting the constitutional order, although no formal party ban has yet been effected. Germany has legal mechanisms to ban parties that promote fascism or seek to undermine the democratic order. This is rooted in the post-World War II Basic Law (Grundgesetz), specifically designed to prevent the rise of totalitarian movements like the Nazis. The BfV, Germany’s domestic intelligence agency has formally classified the AfD as a “right‑wing extremist” organization. This is an attempt to portray popular democratic forces in Germany as fascist in order to suppress them. AfD is not a threat to democracy, but to corporate statism and technocratic control. Globalists are using the principle of defending democracy from intolerance to suppress the populist uprising against globalization. Democrats in the US endeavor to manufacture the same perception about popular democracy, portraying Donald Trump and MAGA as fascists.

However, as noted, Islam is the thing in itself. One need not perform Orwellian meaning inversions to warp words into their opposite. There is no peaceful movement here that requires conjuring to transform into a totalitarian monster. Why Islam is the favored religion by progressives and social democrats across the trans-Atlantic order is rather obvious: corporate statism, the instantiation of fascism in the twenty-first century, finds a useful form of totalitarianism in Islam, useful because it disorders the nation state through demographic recomposition and cultural disintegration, and by disrupting worker solidarity. The hubris of the transnational elite leads them to believe they can harness the force of Islam. But, as history tells us, they are playing with fire. (See Corporatism and Islam: The Twin Towers of Totalitarianism.)

I admitted in one of the essays cited at the top of the present one that I recognized that libertarianism is itself an ideological framework with assumptions about the state’s proper role in society, but I stressed that the libertarian standpoint is not a singular truth, but rather one that affirms the singular truth that authoritarianism negates free and open society. I said in that essay that one cannot simultaneously proclaim support for a free and open society, on the one hand, and then, on the other, restrict arguments, ideas, opinions, and assembly. I still believe this, but on the question of public office, which I had not considered that deeply, I am not sure that it is a contradiction to proclaim support for a free and open society while erecting barriers to office for those who advance a totalitarian ideology—not an ideology the corporate elite say is totalitarian, but one that is on its face totalitarian, which a long history of showing its face.

So my argument that, from a libertarian standpoint, any attempt to police speech—even speech advocating authoritarianism—is itself authoritarian still holds. The principle of free speech indeed only holds if it applies to all viewpoints, including those some find abhorrent. People are free to believe and say what they will. The matter at hand is not a question of whether Muslims have a right to practice an abhorrent religion. Rather, the question is whether non-Muslims have a right not to be treated as second-class citizens in their own country. Not to sound trite, but one cannot have freedom of religion unless one first has freedom from religion. So we must consider whether it violates our principles to safeguard the West from this form of totalitarianism, and if we agree that it doesn’t comprise those principles, then erect the necessary structures that render our society immune from this problem. We need to move quickly. We don’t have much time. Did I already tell you: New York City just elected a Muslim mayor?