Benjamin Netanyahu has spoken about the murders of two Israeli Embassy employees, Yaron Lischinsky and Sarah Milgrim. Shouting “Free, free Palestine,” Elias Rodriguez murdered the couple outside the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington DC. During his arrest, Rodriguez declared, “I did this for Gaza.” Netanyahu correctly assesses the situation in the video shared below: Rodriquez was a weapon cocked and pointed at Jews and their allies loaded by antisemitic sentiment propagated by the Free Palestine movement.

Rodriguez’s action was propaganda of the deed. What prepares the deed is propaganda of the word. And the word here has a long and vicious history. Eliminationist and exterminationist antisemitism are not new phenomena. A deeper history is in order to fully comprehend what the State of Israel is confronting. More than this: what confronts the West. The pro-Palestinian crowd is part of a fifth column operating in several Western states—the Red-Green Alliance–and it seeks to dismantle the Enlightenment and liberal democracy.

I have written about the problem of the fascination Western youth have with anti-Jewish politics and the rise of the leftwing antisemitism (The Growing Threat on Our College Campuses; Why are Western youth Falling in Love with Islam?; The Islamization Project on US College Campuses; Why the Woke Hate the West; Woke Progressivism and the Party of God; Israel’s Blockade of Gaza and the Noise of Leftwing Antisemitism; Jew Hatred and the Normalization of Sociopathy; Occupying Public Spaces is Not Free Expression OR Don’t Stick Metal Prongs in Electrical Sockets; Cornering Jews and the Falsification of History). I have also before written about the antisemitic double standard I explore in this essay (The Danger of Missing the Point: Historical Analogies and the Israel-Gaza Conflict; National Socialism and the State of Israel: The Perpetuation of a False Equivalency; Facing Down Evil), as well as the persistence of antisemitism in history (e.g., Jew-Hatred in the Arab-Muslim World: An Ancient and Persistent Hatred).

Today’s essay is a deep dive into the history of antisemitism and how anti-Jewish sentiment drives politics in the West. The core of this essay has a long development. I wanted to make sure of the historical narrative before publishing it. Before I turn to what I have been able to determine, I want to spend a moment emphasizing the point that criticizing Israel’s state policies falls within the bounds of legitimate political discourse. All states are subject to criticism. Indeed, everything is subject to criticism. Issues such as settlement expansion under cover of occupation, military actions, and treatment of Palestinian Arabs are subject to international debate, as well as domestically within Israel itself.

(I have in the past made some of these criticisms myself, although I admit that many of my arguments from the early 2000s were wrongheaded. I fell under the spell of the academic teachings I critique in this essay. Graduate school in the 1990s was dominated by critical race theory, postcolonial studies, and Third Worldism, and in the context of a near-total institution, I adopted many of those views and used them to criticize those who saw antisemitism lurking behind criticisms of Israel, moreover that the left’s fascination with Islam, especially the Palestinian Arab, is inspired by that ancient hatred. That ancient hatred lies at the core of Islamism.)

However, when such criticisms cross into demonization, such as suggesting something about the character of Jews apart from ideology or religion, employ double standards, or deny Israel’s right to exist (apart from the general problem of presuming such a right for any country in international law), antisemitism is manifest. Indeed, antisemitism drives demonization, double standards, and the desire to see Israel dismantled. Portraying Israel as inherently evil or uniquely genocidal, or invoking classic antisemitic tropes, e.g., global Jewish control or blood libel, transforms political critique into, or more precisely exposes it as ethnic vilification—and political critique becomes a cover for calumny.

One of the most pernicious expressions of this dynamic is the appropriation of settler-colonial language to describe Israel’s founding. The charge that Zionism is a colonial enterprise imports European academic frameworks and ignores the historical and indigenous connection of the Jewish people to the land. Jews are not foreign settlers in Israel; they are a people indigenous to the region, whose dispersion and persecution across centuries culminated in a return—sometimes from Europe, often from the Arab world—to their ancestral homeland. Jewish immigration to Israel was just that: immigration. It was not colonization. In many cases, it was an escape from systemic antisemitism.

The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism offers a framework for recognizing when anti-Israel sentiment becomes antisemitic. It outlines examples such as Holocaust inversion, collectively blaming Jews for Israel’s actions, or delegitimization of Israel’s right to exist—all of which are seen in various corners of Arab political and social life. I have criticized the IHRA’s definition of antisemitism in essays on this platform and in public talks, especially as it is used to form legislation addressing antisemitism; but not all of IHRA’s definition is wrong. What I regard as descriptive of antisemitism is reflected in the IHRA’s definition, so it might be helpful for readers to review that document here: Working Definition of Antisemitism.

Why do I oppose the use of IHRA’s definition in the formation of law? I want to spend a few moments explaining my position on that matter. From my standpoint states should not officially endorse historical claims or interpretations because doing so politicizes history, i.e., using history for partisan political ends, and undermines the integrity of historical scholarship. It risks historical revisionism—for the wrong reasons. History is a field that thrives on critical inquiry, evidence-based analysis, and the freedom to revise understandings as new information comes to light. When a government takes an official stance on historical events, it risks using history as a tool to promote national narratives or political agendas rather than encouraging honest reflection and debate. This can stifle academic freedom, marginalize alternative perspectives, and create a rigid, one-dimensional view of the past that serves current power structures rather than truth.

At the same time, while I believe states should not officially endorse historical interpretations, I do recognize that certain legal contexts—such as laws against genocide—require clear, codified definitions derived from interpretation of historical events. These definitions are not about shaping collective memory but about ensuring accountability, the protection of human rights, and meting out justice. In such cases, the legal recognition of events like genocide serves a necessary function within the justice system, distinguishing it from broader historical interpretation. This kind of legal clarity is essential for prosecuting crimes and upholding international law, as long as it does not preclude ongoing scholarly debate about the complexities of the events in question.

The problem I am identifying is illustrated by the attempt to delegitimize the state of Israel by portraying its actions as genocidal. Israel has faced accusations of genocide, particularly in the context of its military operations in Gaza and its broader policies toward Palestinians. These allegations have been made by various human rights groups, international figures, legal scholars, and some nation-states, especially during periods of intense conflict marked by high civilian casualties and widespread destruction (the consequence of Israel’s military superiority and determined fight for survival). The term genocide in these accusations is typically invoked to highlight what is seen as systematic violence or policies that threaten the survival of a people.

Many governments and legal experts argue that while Israel’s actions may raise serious concerns under international humanitarian law, labeling them as genocide requires meeting a very high and specific legal threshold—namely, the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, an ethnical, national, racial, or religious group (Genocide Convention). To date, no international court has officially found Israel guilty of genocide. Presumably, there would have to be evidence of genocide for an international court to make such a finding. There is no genocide taking place in Gaza. We trust that international courts will not manufacture the perception of genocide by making such a finding. But should we? Can we trust international courts?

Netanyahu has been charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court (ICC). In November 2024, the ICC issued arrest warrants for Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant. The charges pertain to actions taken during Israel’s military operations in Gaza from October 8, 2023, the day after Palestinian Arabs massacred Jews in Israel, to at least May 20, 2024. Specifically, Netanyahu and Gallant are accused of employing starvation as a method of warfare, intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population, and committing acts of murder, persecution, and other inhumane acts. Israel disputes the ICC’s jurisdiction, as it is not a member of the court, and has condemned the charges as politically motivated. Despite this, the arrest warrants obligate the 124 ICC member states, including many European countries, to arrest Netanyahu and Gallant if they enter their territories.

Driving the action of the ICC is an assumption that Israel’s policies are racist (or more precisely ethnicist). The assertion that Zionism is racism reflects the growing influence of newly independent and decolonizing nations—the Third World—within global institutions like the United Nations during the mid-twentieth century. In 1975, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 3379, which declared that Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination. This resolution was backed by the Soviet bloc, Arab states, and many non-aligned countries from Africa, Asia, and Latin America—nations that had recently emerged from colonial rule and were increasingly asserting themselves in international forums.

Many of these states viewed Zionism—the movement for the establishment and support of a Jewish state in Palestine—as a colonial or settler-colonial project that mirrored the systems of racial oppression they had themselves experienced under European imperial powers. For them, the displacement of Palestinians in the creation and expansion of Israel resembled forms of racial domination they associated with apartheid, segregation, or European conquest. In this context, the identification of Zionism with racism was as much a political statement about global power structures as it was a legal or philosophical assessment of Zionism itself.

This framing was—and remains—highly controversial. Western powers, especially the United States and European nations, condemned the resolution, arguing that Zionism was a national liberation movement for Jews, particularly in the wake of the Holocaust. Many saw the resolution as a distortion of human rights language for political purposes.

The double standard is obvious here. In the wake of World War II, the principle of national liberation emerged as a defining force in global politics, driven by a widespread rejection of colonialism and imperial domination. The war had discredited European empires, i.e., the core of world capitalism, exposed the brutality of racial hierarchies, and inspired ethnic populations to assert their right to self-determination. This principle gained legal and moral momentum through the newly formed United Nations, particularly with the adoption of the UN Charter and later resolutions that affirmed the legitimacy of anti-colonial struggles. So why were the Jews not entitled to collective self-determination and national liberation?

Across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, movements for national liberation linked their cause to broader demands for dignity, equality, and sovereignty, challenging the international community to recognize the political agency of formerly subjugated peoples. National liberation became not only a political goal but a moral imperative, reshaping the postwar international order and redefining the meaning of autonomy and freedom on a global scale. Zionism was a national liberation movement in these terms. Yet, the Jewish case was treated differently. Most paradoxically, the Jews were treated as if they were colonizers.

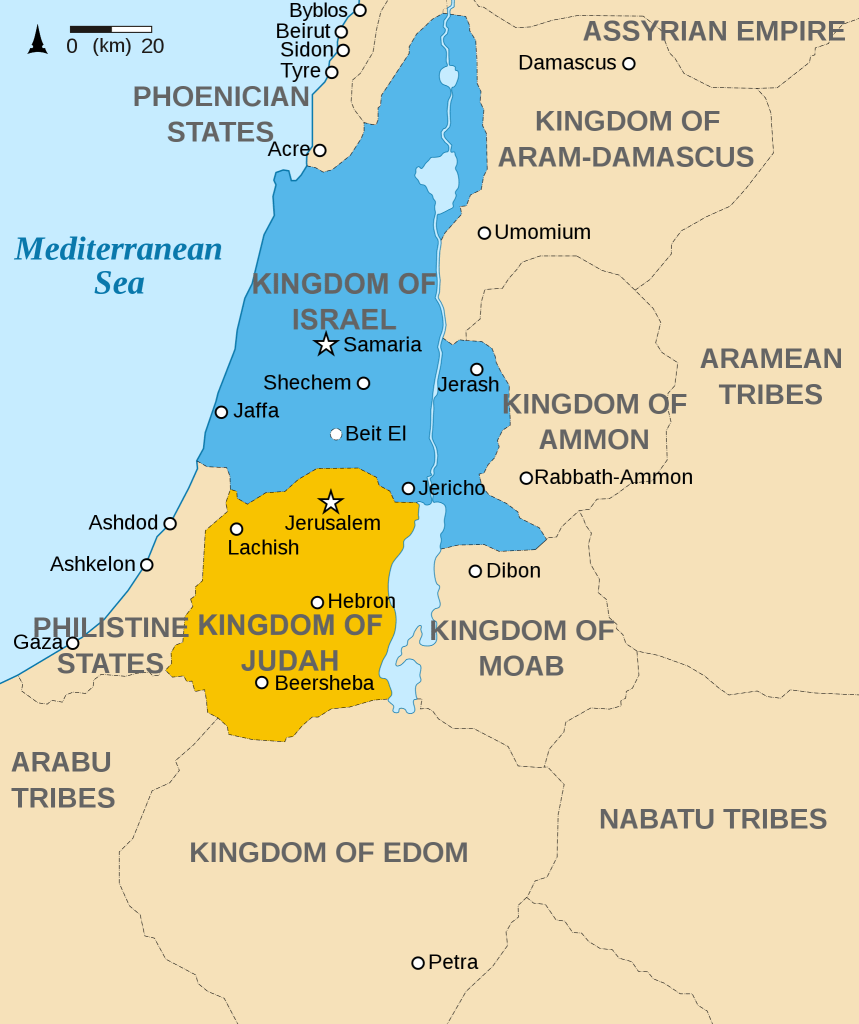

History tells a very different story. The colonization of the Jewish homeland and the forced removal of Jews from their territory spans centuries of displacement, imperial domination, and ethnic persecution. Following the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and the Bar Kokhba revolt c. 135 CE, large numbers of Jews were enslaved, expelled, or exterminated, beginning a long period of diaspora in which Jews were scattered across the Middle East, Europe, and North Africa. Successive empires—including Roman, Byzantine, Islamic Caliphates, Crusader states, and later the Ottoman Empire—dominated the region historically known as Judea, later renamed Palestine.

It was following the Bar Kokhba revolt that the Roman Emperor Hadrian renamed the province of Judea to “Syria Palaestina.” This was part of a broader effort to suppress Jewish identity and connection to the land following the revolt. The name “Palestina” was derived from “Philistia,” referring to the ancient Philistines who had lived along the coastal region of the Levant centuries earlier. This renaming was intended to minimize Jewish ties to the territory and to punish the Jewish population for their rebellion against Roman rule.

However, in terms of deep historical time, this starts the story at a rather recent moment. Long before the Roman destruction of the Second Temple, the Jewish people had already experienced a long and tumultuous history of conquest, exile, and foreign domination at the hands of powerful empires such as the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians. In the eighth century BCE, the Assyrian Empire conquered the northern Kingdom of Israel, leading to the forced deportation of the ten northern tribes and the dismantling of their political and religious institutions. And in the early sixth century BCE, the Babylonian Empire under Nebuchadnezzar II invaded the southern Kingdom of Judah, destroyed the First Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE, and exiled much of the Jewish elite to Babylon, initiating a formative period of diaspora.

When the Persians, led by Cyrus the Great, conquered Babylon in 539 BCE, Cyrus issued a decree allowing Jews to return to their homeland and rebuild the Temple. Yet, while the Persian period marked a partial restoration, the Jewish homeland remained under foreign control, setting a precedent for centuries of imperial rule that shaped Jewish political, spiritual, and national consciousness long before the Roman era.

Throughout these eras, Jews remained a continuous, albeit often marginalized, presence in the land, facing discrimination and periodic violence. Over time, their ties to the land—at least in terms of legal claims—were weakened by external rule, while in many parts of the world Jews endured expulsions, forced conversions, and ghettoization. The colonization of the Jewish homeland was not only to foreign control of the territory but also to the systematic undermining of Jewish self-rule and identity in their ancestral land. This culminated in a deep historical yearning for return and national restoration. Zionism is an expression of the yearning.

Ultimately, Resolution 3379 was revoked in 1991 with the end of the Cold War and, under strong pressure from Western nations, a period of renewed peace efforts began in the Middle East. Thus the equation of Zionism with racism emerged at a time when postcolonial states were reshaping global discourse at the UN, using their collective voice to challenge narratives they viewed as embedded in imperialism and racial hierarchy. This episode underscores the extent to which international law and norms are often shaped by the shifting balances of global political power. But shifting sands must not be allowed to obscure the fact that antisemitism was behind the 1975 resolution. And, despite revocation of Resolution 3379, antisemitism persists. And it is on the rise.

Antisemitism in Slavic countries, including Russia, and plainly evident in Ukraine, has deep historical roots and has manifested in various forms over centuries—cultural, political, religious, violent. While each country in the Slavic region has its own specific history, several shared patterns emerge, particularly regarding state policy, religious influence, and nationalist movements.

In Russia, antisemitism dates back to the time of the Tsars, especially after the partitions of Poland in the late eighteenth century, which brought large Jewish populations into the Russian Empire. Jews were confined to the Pale of Settlement, faced legal restrictions, and were frequently scapegoated for economic and social problems. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, violent pogroms—often tolerated or even incited by authorities—terrorized Jewish communities. The infamous fabricated text The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which became a key antisemitic conspiracy theory worldwide, originated in Tsarist Russia around 1903.

In other Slavic countries, antisemitism also took hold in different ways. In Poland, long-standing religious antisemitism, tied to Catholic identity and accusations such as deicide or ritual murder, fed periodic outbreaks of violence, including the Kielce pogrom in 1946, even after the Holocaust. In Ukraine, antisemitic violence was prominent during periods of political instability, notably during the Russian Civil War and under Nazi occupation, when some nationalist militias participated in pogroms and collaboration.

The roots of antisemitism in the Arab world are multifaceted. While pre-modern Islamic societies often treated Jews as a protected minority (dhimmi), albeit this narrative is often romanticized for political advantage, European colonialism, Arab nationalism, and later the Israeli-Palestinian conflict corrupted this tradition such as it was. With the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the subsequent Arab-Israeli wars, many Jews in Arab countries were expelled, fled violence, or left under state pressure. Their departure left a vacuum filled by state-sanctioned narratives that portrayed Jews not merely as political enemies, but as existential threats to the world. These narratives—embedded in antisemitism—falsely cast Jews who immigrated to Israel as colonial agents.

Antisemitic sentiment in any areas of the Arab world has been influenced by a mix of cultural, historical, political, and religious factors, including colonial and post-colonial narratives. Nationalist movements sometimes portrayed Jews as aligned with Western colonial powers or as alien intruders, despite Jews’ ancient ties to the region. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has further led to a conflation of Jews with the policies of the State of Israel, fueling hostility toward Jewish people generally, with educational curricula reinforcing this conflation. Media and religious rhetoric often propagate antisemitic tropes or conspiracy theories, erasing the historical fact that Jewish immigration to Israel was often an act of survival and return, not conquest.

In several countries—including Egypt, Iraq, Syria, and the Palestinian territories—antisemitic rhetoric became commonplace in public discourse, sermons, speeches, and textbooks. Conspiracy theories, such as The Protocols, were widely circulated and became entrenched in Islamist thinking. For example, Hamas has referenced The Protocols in its ideological texts, particularly its 1988 charter, Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement. The charter includes explicit antisemitic rhetoric and cites the Protocols as if it were authentic, using it to support its allegation of a vast Jewish cabal.

Across much of the Arab world, in educational, media, and religious institutions, Jewish identity is often conflated with Zionism—a political and nationalist movement that emerged in the late nineteenth century with the goal of establishing a Jewish homeland in the historic Land of Israel. Zionism is frequently equated with racism or colonialism, a formulation that erases the indigenous nature of Jewish connection to the land and treats Jewish self-determination as an imperialist project. The result is a cultural environment where anti-Israel sentiment and antisemitism have become mutually reinforcing, and where legitimate grievances are often expressed through delegitimizing and dehumanizing language.

In Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Syria, one finds consistently high levels of antisemitic sentiment in public rhetoric and surveys. In the Palestinian territories, particularly Gaza under Hamas, antisemitic propaganda is intertwined with resistance narratives. Lebanon, under the influence of Hezbollah, maintains a strongly anti-Israel stance with rhetoric that crosses into antisemitism.

To be sure, countries such as Bahrain, Morocco, and the United Arab Emirates have made efforts to promote interfaith dialogue and preserve Jewish heritage. Morocco, for example, incorporates Holocaust education into school curricula and has restored synagogues and Jewish cemeteries. Bahrain and the UAE, following the Abraham Accords, have made overtures toward Jewish communities and supported cultural exchange. However, even in these contexts, antisemitic attitudes persist among segments of the population. The very need for these governments to pursue such efforts is testament to how deeply rooted antisemitism remains—even where formal policy changes occur.

The modern Arab world presents a complex landscape where antisemitism and anti-Israel sentiment frequently intersect—and this is because anti-Israel sentiment is driven by antisemitism. So, while it is crucial to distinguish legitimate criticism of the State of Israel from antisemitism, as I stress earlier, it is equally important to recognize that a significant portion of anti-Israel rhetoric in the Arab world is driven by or infused with antisemitic beliefs. This phenomenon is shaped by media representation and societal narratives that have developed over generations—fueled by the fallacy that Jews are colonial outsiders in their own land.

Thus, whatever anti-Israel sentiment in the Arab reflects genuine political grievances, the enemies of Israel draw on antisemitic beliefs and this is manifest in the misapplication of colonialist frameworks to Jewish history and identity. Anti-Jewish sentiment is part of a broader anti-Western antipathy, where the West alone is associated with colonialism and imperialism, this despite the fact that such practices are centuries old and global.

The ideological conflation of Zionism with colonialism, and Jews with foreign interlopers, is not confined to the Middle East. On university campuses in the United States and several European countries, pro-Palestinian activism has grown in visibility and intensity, especially following Hamas’ massacre of more than a thousand Jews in Israel on October 7, 2023. While some of this activism reflects sincere concern for Palestinian Arabs in occupied territories and in Gaza, it is nonetheless shaped by a worldview in which Zionism is cast as a colonial ideology and Jews as representing white settler power—despite the obvious historical incoherence of such framing.

However, the argument that this ancient hatred has migrated into Western discourse, particularly among academic and progressive political circles, is not quite correct. The Arab perspective borrows heavily from postcolonial theory and intersectional frameworks developed by Western intellectuals, in which Israel is analogized to apartheid South Africa and even to Nazi Germany—comparisons that rely on antisemitic tropes and historical revisionism. These frameworks erase or minimize Jewish indigeneity to the region, as well as the presence of Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews, who constitute a significant portion of Israel’s population and whose migration to Israel was largely involuntary and trauma-driven. Within this ideological structure, antisemitism is dismissed, redefined, or even justified under the guise of anti-Zionism (presuming this is a legitimate position), despite its clear resonance with classic forms of anti-Jewish hatred.

Thus, the academic and activist atmosphere has not remained merely theoretical. It has contributed to a cultural climate in which antisemitic speech and, increasingly, antisemitic violence, are tolerated, excused, or advocated. The killings in Washington, DC mark an escalation in the consequences of this radicalization. Such acts of violence underscore the degree to which certain forms of anti-Israel activism have crossed the line into racial and religious hatred. That the couple was targeted explicitly because of their Jewish identity—and not any political activity, which would not justify the assassin’s actions in any case—drives home the point that antisemitism, not critique of policy, was the motive.

The response from the US government under President Donald Trump to the rise of antisemitism has been swift. The Trump administration, citing the surge in campus antisemitism and the apparent inability—or unwillingness—of elite universities to contain it, has begun pulling federal funding from some institutions under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. Most notably, Harvard University has had its certification to accept foreign students revoked. (This action was not based solely on the issue of antisemitism. It was influenced in part by longstanding concerns over foreign influence on US higher education, particularly the infiltration of Chinese Communist Party-aligned entities into American academic institutions.)

This intersection—between antisemitism cloaked as activism, ideological importation of fallacious settler-colonial narratives, and institutional failure—represents a crisis of both governance and values in Western liberal democracies. Universities, which should serve as bastions of critical thought and ethical discourse, are increasingly becoming echo chambers where nuance is unwelcome, and historical complexity is reduced to binary slogans. In this environment, Jewish students are being harassed and silenced, excluded from progressive spaces unless they renounce any identification with Israel.

What is most alarming is not that criticism of Israeli policies is taking place—that is expected and, in many cases, warranted—but that such criticism is being advanced within frameworks that require the erasure of Jewish history and legitimacy. As in the Arab world, antisemitism is not a reaction to Israeli state actions; rather it is antisemitism that shapes how those actions are interpreted and how Jews are portrayed as a people. It is precisely this inversion of history and morality that makes antisemitism so dangerous: it adapts to every ideological moment, whether nationalist or progressive, religious or secular.

To combat this, it is not enough to issue condemnations after violent incidents or to gesture toward pluralism in abstract terms. What is required is a robust and unapologetic defense of historical truth: that Jews are not colonial interlopers in the Middle East, but indigenous people who have returned to a land from which they were violently exiled; that Israel’s existence is not a Western colonial outpost (although it is an outpost of the Enlightenment and Western values and rational, secular principles), but the political realization of Jewish self-determination; and that antisemitism—whether dressed in the garb of jihad or justice—is an ancient hatred wearing modern clothes.

The Western intellectual has played a chief role in this. While anti-Zionism and antisemitism in the Arab world have deep indigenous roots—shaped by the experience of colonialism, perceived historical grievances, and religious tradition—the postcolonial framing that casts Israel as a settler-colonial state the Arab world has adopted has been significantly influenced by Western academic and leftist thought.

It may strike readers as odd that, beginning in the mid-twentieth century and accelerating with the global spread of postcolonial theory, Arab intellectuals and political movements began to adopt the vocabulary and conceptual apparatus of Western progressivism. European Marxist and post-structuralist/structuralist thinkers reinterpreted global conflicts through a colonizer-versus-colonized lens, the oppressor-victim trope, a model that resonated with Arab narratives of dispossession but also reshaped them.

International institutions helped amplify this shift. The United Nations and the Non-Aligned Movement, particularly during the Cold War, disseminated the language of anti-imperialism on a global scale. The aforementioned 1975 UN Resolution 3379, which declared Zionism a form of racism, exemplifies how Western intellectual and political frameworks were adopted to codify and internationalize a narrative that previously existed in a more nationalistic or religious register.

Thus, Western academic circles—particularly in elite universities corrupted by postmodernist thought—exported a model of decolonial rhetoric and intersectional politics. These frameworks reframe the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a paradigmatic case of racialized colonial oppression. Arab discourse has not only absorbed these narratives but amplified them, finding in them both a justification for existing hostilities and a new language through which to express them—a language that appeals to Western youth radicalized in the universities (and even earlier in the educational process). Thus, while the emotional and political opposition to Israel is substantially local, the conceptual framing that dominates Arab and international discussion today is a hybrid—indigenous resentment expressed through the imported grammar of Western radicalism.

The adoption of a colonizer-versus-colonized framework by European Marxist and post-structuralist/post-modernist thinkers—and its subsequent embrace by Arab political discourse and Western academic institutions—reveals more than an analytical shift. It signals a deeper ideological realignment—the Red-Green tendency—that pits the West not simply against past imperial excesses (again, not unique in history) but against liberal modernity itself.

This interpretive model, ostensibly designed to critique power, inverts historical and moral clarity, casting liberal democracies as oppressors and authoritarian movements as agents of liberation. It smuggles in clerical fascism via the Trojan Horse of critical race theory and social justice rhetoric. The consequence is a paradoxical embrace of reactionary, even theocratic, politics under the guise of progressive struggle.

What emerges is not any real solidarity with the oppressed, but a form of Third Worldist romanticism that elevates any opposition to the West—however antisemitic, regressive, or antisemitic—as morally superior. This anti-Western stance increasingly tolerates, excuses, or sanctifies authoritarian ideologies, including jihadist movements, so long as they align against Western liberalism.

Such a worldview not only distorts history but corrodes the moral foundations of Western society. The anti-Jewish rhetoric embedded in today’s pro-Palestinian activism—rhetoric that erases Jewish history, denies the legitimacy of Jewish self-determination, and justifies terrorism—must be understood not as a fringe aberration but as a logical outcome of ideological drift and a convergence of anti-Western sentiment. As I have discussed in previous essay, what lies behind this is transnational corporate power.

When critiques of Western power abandon democratic norms and universal human rights in favor of binary moral absolutism, they do not elevate the oppressed—they empower those who would suppress freedom under the banner of resistance. The West is not perfect, to be sure, but to deny its role as a flawed but vital incubator of liberty, pluralism, and reason is to surrender the intellectual tools necessary to confront real oppression to destructive ideology. At the risk of sounding chauvinistic, the West is the moral center of the human universe. This is obvious with even a cursory glance across the world system. Why are Western youth apologists for the Chinese Communist Party, the real-world instantiation of George Orwell’s nightmare world depicted in his Nineteen Eighty-Four?

In a recent essay, I argued for counter-speech to address growing anti-Jewish, and more broadly the anti-white, sentiment associated with discriminatory policy and ethnic and racial violence. The task ahead is difficult but not impossible. It demands courage from educators, integrity from activists, and vigilance from policymakers. Most of all, it demands a renewed commitment to distinguishing criticism from calumny, and protest from prejudice. Without that distinction, the path forward will not lead to justice or peace, but to further hatred—and more graves.

Breaking the cycle of antisemitism in the Arab world requires more than diplomatic normalization with Israel. It demands grassroots education, honest historical reckoning, and public engagement that doesn’t separate Jewish identity from the political conflict but explains that the political conflict is largely caused by Jewish identity—not by Jews, but by antisemites. Raising this awareness requires challenging the false narrative that portrays Jews as colonial interlopers. Jews are not foreigners in the Middle East—they are an indigenous people with a millennia-long presence, who, like many others, have been subjected to persecution, displacement, and exile.

Debunking mythology and exposing historical revisionism is essential not only for combating hatred, but for building a future in which Arabs and Jews—whether in the Middle East or beyond—can coexist in mutual respect. An important element of the work is liberating Arabs, Persians, and others from Islam. The challenge lies not in silencing criticism, but in ensuring it does not become a vehicle for age-old prejudice masked as political analysis.