Earlier this month I revisited the problem of crime Ferguson, Missouri (see Ferguson Ten Years Later). As a criminologist who began his career by examining the role of social structure and class inequality in fostering criminogenic conditions and public responses, I’ve come to recognize that the culture that pervades high-crime areas significantly contributes to the persistence of crime, disorder, and violence. While I continue to work from the materialist conception of history, and view culture as emergent from underlying structural conditions, I recognize that once a particular culture takes root, it not only persists but also dialectically reinforces the very structures that produced it. In this way, culture functions akin to an ideology, reproducing a system of social norms and relations that perpetuates the existing conditions. Therefore cultural critique cannot be eschewed by scholars working from the historical materialist standpoint. (See Mapping the Junctures of Social Class and Racial Caste; Marxist Theories of Criminal Justice and Criminogenesis)

The dissolution of the nuclear family can be seen as both a consequence and a catalyst within this dialectical relationship between structure and culture. Economic inequalities and structural dislocations, exacerbated by progressive state policies, have eroded traditional family structures, particularly in high-crime areas, leading to fragmented family units that struggle to provide stability and socialization for children. As these weakened family structures become more prevalent, they contribute to the perpetuation of a culture that normalizes and even necessitates alternative social arrangements, often reinforcing patterns of crime, disorder, and violence. This cultural shift further entrenches the structural conditions that undermine the nuclear family, creating a feedback loop that perpetuates social instability. In this way, the disintegration of the nuclear family both reflects and reinforces the broader systemic issues that drive inequality and social dysfunction.

In this essay, I explore the problem of culture and the family in high-crime areas, focusing on how the dissolution of the nuclear family both reflects and reinforces the broader systemic issues that perpetuate crime and social dysfunction. I argue that a scaling up of the defense mechanism of reaction formation, alongside the problem of learned helplessness, plays a critical role in this dynamic. As traditional family structures erode, the resulting cultural shifts contribute to a cycle of disempowerment and maladaptive behaviors, which in turn sustain the conditions that undermine social stability. To lay the groundwork for this analysis, I begin with a brief history of the nuclear family and the culture of dependency associated with slavery.

Western civilization is the most advanced and dynamic sociocultural system to appear in world history. At its core is the integrity and stability of the nuclear family. The history of the nuclear family in the West is deeply intertwined with broader cultural, economic, and social transformations over centuries. Typically defined as a household consisting of two parents and their children, the nuclear family has its roots in pre-industrial Europe, It became widespread with the advent of industrialization and the rise of modern capitalism. By the nineteenth century, the nuclear family ideal prevailed everywhere in the West, reinforced by the rising new middle class, which promoted values of individualism and the sanctity of the home. The nuclear family was a haven from the harsh realities of the industrial world, with the home being a place of emotional and moral support. Thus is served a protection function against the chaos generated by the dynamic of the capitalist mode of production. In the twentieth century, the nuclear family became even more entrenched, particularly in the post-World War II era. The economic boom of the 1950s in the United States and Western Europe saw a renewed emphasis on the nuclear family as the cornerstone of a stable and affluent society. The suburbanization of Western societies also played a role in perpetuating the nuclear family model, as planners designed suburban communities to accommodate this type of family structure.

We need to back up a bit in time and pick up a thread that weaves its way through the tapestry: the problem of slavery. Modern Western society emerged in a world where slavery had been a common practice for thousands of years. Slavery is inherently destructive to the family, as it imposes an external power that dictates the terms of people’s lives, fostering dependency and undermining family structures. In the West, some nations integrated slavery into their economic systems. For example, before the establishment of the United States, slavery had become widespread in the Southern colonies of the British Empire, giving rise to a slavocracy that persisted even after the American Revolution, where it became closely aligned with the Democratic Party. In this system, enslaved labor primarily consisted of people of African descent. Over time, Western civilization would abolish slavery throughout its territories, with the United States fighting a catastrophic civil war to end the practice. However, the legacy of centuries of slavery and its devastating impact on black families took decades to overcome.

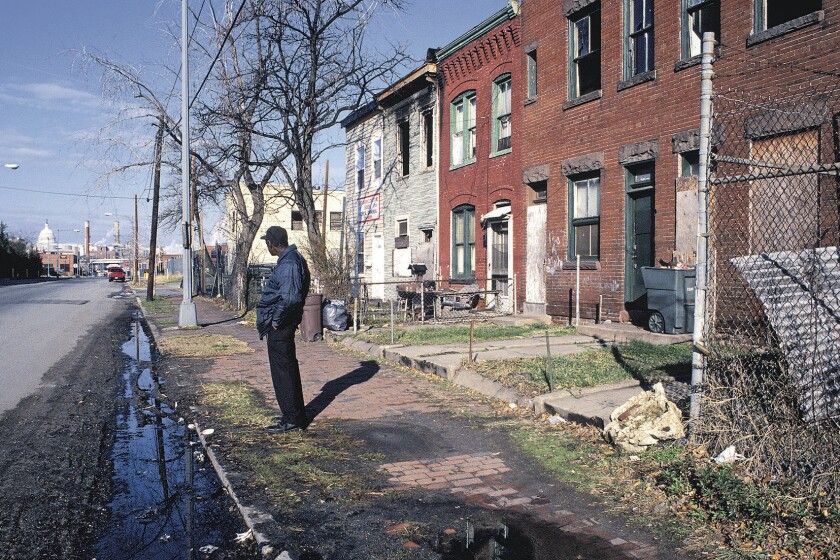

After slavery was abolished in the United States, the Reconstruction era began, offering a brief period of hope and progress for newly freed black Americans. During this time, significant strides were made in establishing relatively autonomous black communities. Even after the end of Reconstruction, the nuclear family became increasingly common in black communities, providing stability and fostering a strong sense of determination and individualism. In the twentieth century, the Great Migration saw millions of black Americans move from the rural South to urban centers in the Northeast and Midwest. Black families continued to thrive amid ghettoization, developing a vibrant culture, marked by economic growth, educational advancement, and strong family bonds. However, this progress began to unravel in the 1960s, when a combination of factors, including urban decay, economic disenfranchisement, and the rise of welfare policies, led to the breakdown of the black nuclear family and the ghettoization of black communities.

This unraveling was overseen by the progressive wing of the Democratic Party. Divorce and never married rates rose drastically and the single-parent family emerged. Today, the dependent female-headed has become the norm in Blue Cities, that is those urban areas run by the Democratic Party. Today, around 80 percent of black children are born out of wedlock. This situation is perpetuated by a lack of education and dependency on public assistance for food, housing, and medicine. These conditions are further exacerbated by mass immigration, with foreign labor displacing the black worker. It is a vicious circle that blacks feel they cannot escape; demoralization and fatalism are hallmarks of the ghettoized population. The absence of the nuclear family is the single greatest predictor of crime and disorganized communities, and it is progressive social policy that has disintegrated the black nuclear family. (See America’s Crime Problem and Why Progressives are to Blame; The Crime Wave and its Causes; In Need of Cultural Reformation.)

How do progressives rationalize what they did to black people? How are they able to keep black Americans under the thumb of the Democratic Party? Progressives argue that the nuclear family is the oppressive expression of the white supremacy, which they not only attribute to conservatives in America’s heartland but the character of the Republic itself (see Disrupting the Western-Prescribed Nuclear Family Requirement). Conservatives don’t run the Blue Cities; they have no influence there. Ideological hegemony in America’s sense-making institutions allow progressives to manufacture and deploy a massive misdirection play; Democrats redirect the anger and resentment of black Americans justifiably feel towards their plight away from the progressive policies that secure the status quo and towards the foundational elements of American civilization—individualism, industriousness, initiative, limited government, respect for property—portrayed as the destructive expressions of whiteness. As a result, many people living in the ghetto resist doing the things that will improve their lives because they perceive these to be the very things that keep them down. Moreover, they generally lack the education and skills to achieve these things. To put this in psychoanalytic terms, Democrats have produced reaction formation on a mass level. Combined with learned helpless and demoralization, reaction formation perpetuates a destructive culture of dependency.

Reaction formation is a psychological defense mechanism in which a person unconsciously transforms an unacceptable or stress-inducing feeling, impulse, or thought into its opposite. For example, someone who harbors feelings of hostility towards a person who is oppressing or undermining them might behave in an overly friendly or affectionate manner toward that person. This mechanism helps to protect the individual from experiencing discomfort or guilt associated with his true feelings, which typically reside at the unconscious level, pushed deep down into the mind because of the individual’s inability to control the situation and the pain associated with the inability. In the societal-level version of reaction formation, collaborators in the ghetto—black activists, educators, intellectuals, politicians, social workers—are tapped and function to redirect the feelings of anger and resentment among the population towards the political party that did not cause their circumstances (the Republican Party) while portraying those responsible for the situation of blacks as allies (the Democratic Party). Mass reaction formation is pushed deep down into the collective unconsciousness of ghetto dwellers.

(I have suggested reaction formation as an analytical device in several previous essays. Here are some of them: “This Goes On”: Did Arbery Die to Perpetuate a False Narrative About Contemporary American Society?; The Problematic Premise of Black Lives Matter; The Myth of Racist Criminal Justice Persists; Progressives, Poverty, and Police: The Left Blames the Wrong Actors; “If They Cared.” Confronting the Denial of Crime and Violence in American Cities; Working Class Concern About Low-Income Housing is Not Intrinsically Racist; The Line from Slave Patrols to Modern Policing and Other Myths. For more on the problem of BLM, see What’s Really Going On with #BlackLivesMatter. See also Corporations Own the Left. Black Lives Matter Proves it.)

Reaction formation accompanies learned helplessness, which is a situation where individuals repeatedly face situations where they feel powerless to change their circumstances, leading them to believe that they have no control over their environment. This is expressed as fatalism. As a result, individuals suffering from this condition become passive and avoid taking action, even when opportunities for improvement arise. When this condition is coupled with dependency, it can lead to a preference for idleness over work, distraction over focus. The individual comes to rely on others or external support systems, believing that their own efforts are futile or unnecessary. Thus a cycle of dependency is perpetuated where the person becomes increasingly disengaged from education, work and other productive activities, reinforcing their sense of helplessness and therefore perpetuating dependency. The imposed reaction formation entrenches the vicious circle by turning the victims against those who might break the cycle and endearing them to those who perpetuate it.

In The Conditions of the Working Class in England, published in the mid-nineteenth century Friedrich Engels developed an early theory of demoralization, where the harsh realities of impoverished living conditions lead people to become disillusioned with society and its laws. According to Engels, the conditions faced by the underclass foster alienation, hopelessness, and resentment that, in turn, erode respect for legal and moral norms. As people struggle to survive in these conditions, they may turn to crime and violence as a means of coping with or resisting their circumstances. This breakdown of social order, rooted in systemic inequality, contributes to higher rates of crime and further perpetuates the cycle of poverty and social decay. Engels’ theory asks us to focus on the link between economic deprivation and the degradation of social and moral values, illustrating how structural conditions can lead to widespread disorder and lawlessness that finds it justification is a culture of nihilism. (See Demoralization and the Ferguson Effect.)

The complex interplay between structural conditions, cultural dynamics, and psychological mechanisms has deeply influenced the trajectory of black communities in the United States, particularly since the 1960s. The breakdown of the nuclear family, driven by a combination of economic disenfranchisement, urban decay, and welfare policies, has created a cycle of dependency, helplessness, and demoralization that continues to perpetuate social disorder. The progressive wing of the Democratic Party, through ideological manipulation and the promotion of reaction formation on a mass scale, has effectively redirected the legitimate grievances of black Americans away from the policies that have contributed to their plight and towards a destructive critique of the foundational values of American society. This misdirection play not only entrenches a culture of dependency but also inhibits efforts to break the cycle and foster genuine empowerment and self-reliance. Systemic inequality, coupled with the erosion of moral and social norms, demoralizes people, and this leads to the perpetuation of crime and violence.

Addressing these issues requires not just policy changes, but a fundamental shift in the cultural and mass psychological landscape of affected communities, where the nuclear family and individual agency are once again seen as cornerstones of social stability and cultural integrity. It moreover requires a change in the thinking of those who care about the plight of black people and are in a position to influence others. Over the course of my studies, I’ve come to a deeper understanding of the role that culture plays in sustaining high-crime areas. My analysis remains rooted in the materialist conception of history, and in this way of seeing society it is understood that once a culture is established it reinforces the structures that gave rise to it. This dynamic means that culture functions like an ideology, perpetuating the social norms and relations that maintain the status quo. Consequently, scholars who adhere to a historical materialist perspective cannot afford to overlook the importance of cultural critique in addressing the complex interplay between structure and culture in the perpetuation of social conditions. Doing so is not grafting conservative thought on historical materialism, but more fully understanding the analytical scope of Marxian method.