“The media may not always be able to tell us what to think, but they are strikingly successful in telling us what to think about.” —Michael Parenti, Inventing Reality

“The law should be like death, which spares no one.” —Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws

We have to address the double standard that’s in play on the progressive left—and in the media that organizes the corporate state narrative. There is a constant barrage of propaganda from progressive leaders, including those in public office, that ICE is coming into communities, taking illegal aliens into custody, and breaking up families. It’s ugly, these leaders note, and the mass media is supporting the narrative by highlighting its ugliness. Behind this is a double standard that deceives the public about law enforcement activities and family separation.

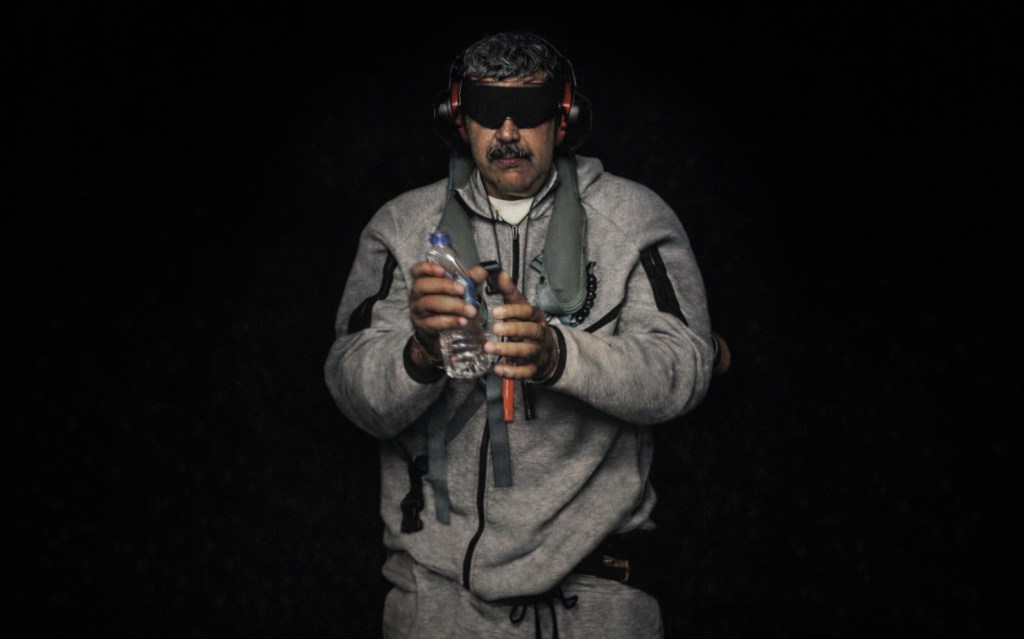

I warned you that when Trump came into office and started enforcing immigration law as promised (why the public returned Trump to the White House in a landslide), it would be ugly. How could it not be? People are taken into custody against their will. There’s a great deal of crying. Screaming. Going ragdoll. Sometimes those taken into custody resist, and force is used. Sometimes people get hurt.

However, when a citizen breaks the law, if he is apprehended, he is taken into custody and, if charged and convicted, often sent to jail or prison. Here, too, is drama. The drama happens every day in America—hundreds and thousands of times a day. Sending parents to prison breaks up families. Loss of liberty and family separation are consequences of breaking the law. They are an inherent part of the criminal justice process. It’s the decision of the lawbreaker that causes his loss of liberty and separation from family. The alternative would be not to enforce the law.

One could never grasp the extent of family separation among the citizen population from watching the media. But, from a statistical standpoint, family separation caused by the US criminal justice system dwarfs that caused by immigration enforcement. Each year, police make roughly 7.5 million arrests, and about 1.9 million people—overwhelmingly citizens—are incarcerated at any given time, routinely separating parents from children through arrest, pretrial detention, and imprisonment.

By contrast, ICE arrests are on the order of around 150,000 per year, with tens of thousands in immigration detention at a time. Even accounting for large numbers of border “family unit encounters” (which Trump effectively stopped with his border control measures), immigration enforcement operates at a vastly smaller scale.

Ordinary Americans can’t know this because, while family separation is a common and normalized consequence of criminal law enforcement for citizens, it receives no media or political coverage. Instead, they are bombarded today, every day, all day, with linear and social media images and reels of the ugliness of immigration enforcement.

“If the press cannot mold our every opinion,” writes Michael Parenti in his 1986 Inventing Reality, “it can frame the perceptual reality around which our opinions take shape.” This is a significant observation: “Here may lie the most important effect of the news media: they set the issue agenda for the rest of us, choosing what to emphasize and what to ignore or suppress, in effect, organizing much of our political world for us.”

Beneath the mediated perceptions, the same principle is in operation in both instances: there are consequences to breaking the law, and family separation is a potential consequence. If one works from principle, then either he believes that all civilians, whether citizen or immigrant, should be held accountable for lawbreaking, or he believes that no civilian, regardless of immigration status, should be held accountable for lawbreaking. There is no choice from the established principled position. It is an either/or. Which is it?

If you assert a principle I am unaware of, and believe there should be a double standard, that citizens should be held accountable but not immigrants, then the question you must answer is why immigrants should be granted immunity from the consequences of breaking the law, while citizens should be denied such immunity. Why would you believe this? What explains the double standard you advocate? What is the principle in operation? The principle needs to be announced and explained, and the public needs to agree that the principle makes sense, before it can be allowed to determine policy. This is a democracy operating under the rule of law. So why should the rule of law be suspended for immigrants?

To all those who support immigration enforcement in the abstract but are troubled by the ugliness of law enforcement action, ask yourselves: if you were to see a glut of media reports showing the ugliness of citizens being taken into custody and families separated, then would you conclude that we should stop all law enforcement? To be sure, there are those on the fringe who advocate for the abolition of policing in principle, but that’s probably not you.

If you say “no,” which I think most of you would, then you mustn’t let emotions carry you away when you see illegal immigrants taken into custody. Progressive leaders and the mass media have selectively weaponized empathy to lead you away from principle. They are programming you to react emotionally and not logically. You have already agreed that lawbreakers should be held accountable. Work from the rational part of your brain, not the emotional part. This does not mean that you shouldn’t have compassion and sympathy for the plight of people taken into custody. It means you put principle over reaction.

If you say “yes” after a gut check, then you don’t really believe in immigration law even in the abstract, because you don’t believe in policing generally. You’re a functional anarchist who is putting the safety of his own family in jeopardy, since the certain result of leaving illegal aliens to reside in the United States will be an increase in crime and violence in your neighborhood. And it you move to depolice at scale, then your neighborhood will descend into anarchy.

Expect the rationalization from progressives that citizens have a higher rate of crime than immigrants. You might ask whether that comparison is between citizens and illegal aliens, not immigrants overall. However the fact is specified, even if it were true, it is immaterial to public safety, since it is certain that a percentage of immigrants will break the law, and that means that more immigrants will increase the volume of crime.

Moreover, many illegal immigrants are, by definition, criminals. Under federal law, Title 8 USC § 1325, it is a misdemeanor to enter or attempt to enter the United States at an undesignated place or time, to elude immigration inspection, or to enter by false or misleading statements. Title 8 USC § 1326 makes it a felony for a person who has previously been removed or deported to reenter, attempt to reenter, or be found in the United States without authorization, with penalties that increase based on prior criminal history. That covers a great many illegal aliens.

To be sure, mere unlawful presence, such as overstaying a visa, is generally a civil violation rather than a crime, though related conduct may be criminalized under other statutes, including 8 USC § 1324 (harboring or transporting undocumented persons), 8 USC. § 1306 (failure to register), and 18 USC §§ 911 and 1546 (false claims to US citizenship and immigration document fraud), but violation of civil law is still illegal conduct. Just because an action is not criminal does not make it legal.

To close the loop on this, although unlawful presence may be a civil matter if no criminal activity is present, the law is still enforced by ICE, authorized by the Immigration and Nationality Act, codified in the same title: 8 of the US Code. 8 U.S.C. § 1227(a)(1)(B) provides that any noncitizen present in the US in violation of law is deportable, forming the principal basis for civil removal proceedings initiated by ICE.

It doesn’t stop there. Title 8 USC § 1182(a)(9)(B) imposes civil consequences for accrued unlawful presence by rendering a noncitizen inadmissible for three or ten years after departure, depending on the length of unlawful presence. DHS’s authority to inspect and determine admissibility derives from 8 USC § 1225, while the procedures governing civil removal proceedings are outlined in 8 USC § 1229a. ICE’s authority to arrest and detain noncitizens pending removal is provided by 8 USC § 1226, and related civil registration requirements appear in 8 USC §§ 1302–1304, all of which operate within a civil, not criminal, enforcement framework, but nonetheless fall under ICE’s purview.

Another rationalization one hears is that ICE officers are glorified mall cops, or, alternatively, private contractors. ICE agents receive their foundational training primarily at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers (FLETC) in Glynco, Georgia, which serves as the main academy for other federal law enforcement agencies.

Training differs depending on the agent’s role. Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) officers, who handle immigration arrests and removals, complete an eight-week program that covers immigration law, constitutional protections, de-escalation techniques, firearms safety and qualification, defensive tactics, emergency driving, and physical readiness. Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) special agents, who focus on criminal investigations such as human trafficking and smuggling, undergo a longer pipeline that combines the Criminal Investigator Training Program at FLETC (around 12 weeks) with agency-specific HSI training (around 13 weeks), providing more in-depth instruction in investigative techniques.

Across all programs, ICE training emphasizes constitutional and statutory law, investigative skills, firearms and defensive tactics, fitness and physical readiness, and de-escalation strategies. After academy graduation, officers enter a supervised field training phase and continue receiving ongoing education, refresher courses, and specialized instruction throughout their careers. So, not mall cops or private contractors. Federal law enforcement officers.

There’s no way to rationalize one’s way out of this. If you are an alien who is not authorized to be in the United States, your illegal presence is subject to law enforcement action. Any attempt to interfere with law enforcement action is criminal, as I showed in yesterday’s essay, Loretta and Richard: The Renee Good Shooting and Correct Attribution of Blame. And be aware that they use real bullets.

Those separating ICE from other law enforcement bodies are arguing from a false dichotomy. They’re assuming or demanding a double standard without a principled reason for their demand. So, the next time you are arguing with progressives, demand from them the principle in operation. If they have one, then tell them to elect representatives who will codify the double standard. Until then, hitting the streets to interfere with ICE operations is the same as interfering with any other law enforcement activity. It’s a crime. Those doing the interfering should be rolled up with the illegal aliens with whom they ally—personal liberty and family separation be damned. Actions have consequences.