“In a time of deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” —not George Orwell

Imagine a professor drawing up and circulating a petition to have a student expelled from the university because he disagrees with a student’s belief in creationism or intelligent design. The student runs a platform from which he promulgates this theory, which is widely shared among the public.

As an evolutionist, I am startled by how widespread belief in creationism is among Americans. According to a May 2024 Gallup poll, 37 percent of US adults identify as “creationist purists,” meaning they believe that God created humans in their present form within the last 10,000 years. As a libertarian, I am committed to the right of Christians to believe that the Earth is young (or old, from their perspective) and that God created and populated it with all the things we see with our very own eyes.

However, this professor I am imagining, a progressive, insists that, because his identity as an evolutionist is sacrosanct, and the theory calls his identity into question—the theory is bigoted, even dangerous. It offends him and, moreover, makes him feel unsafe. The professor thought the university was a safe space in which he would not have to suffer the presence of students in his classroom—or on campus—who advance ideas that question his identity. The university, therefore, should expel the student. At the very least, the university should issue a statement affirming his identity.

How likely is it that the professor could get other professors to sign his petition? Not very likely, one would hope. Assuming the best of professionals committed to academic freedom and the First Amendment, his colleagues would say that students are free to believe what they will, and that it was not his or their role to gatekeep ideas by punishing students with disagreeable ideas. Indeed, again assuming the best, they would worry that the professor was not committed to or at least sufficiently tolerant of the values of a free, open, and questioning society promoted by the university at large.

After all, academic freedom is not just for professors, but for students, too. Indeed, the noble professors I am supposing consider the problem in this situation not the student but the professor. Some even expect the dean to call the professor to his office and ask him why he would do such a thing. All students are welcome here, the dean would say. Viewpoint diversity is essential to the Enlightenment project.

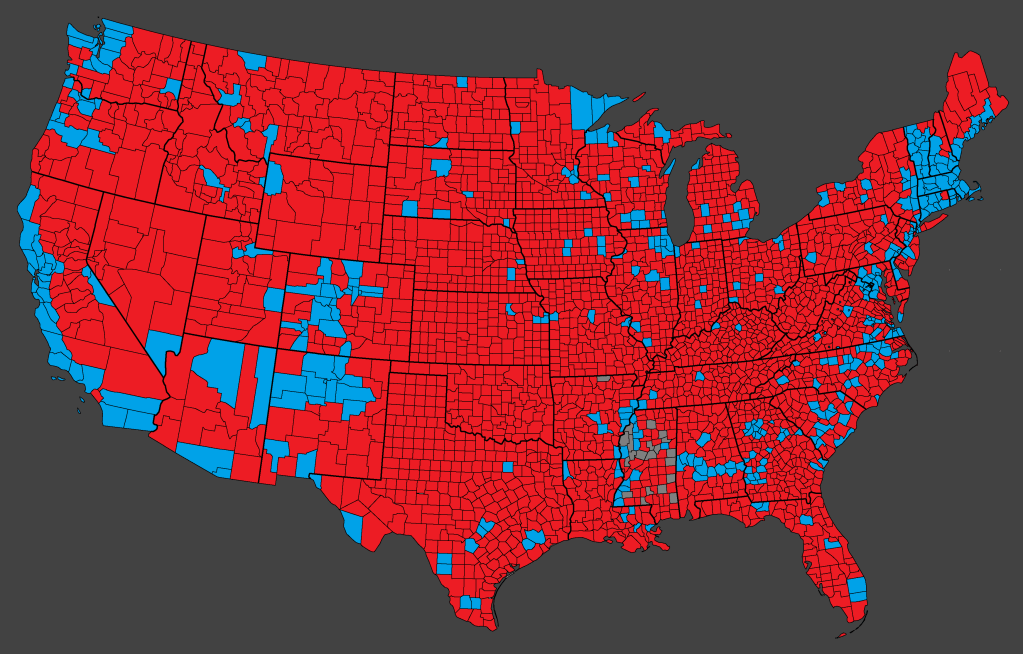

Now, let’s suppose the theory in question is the proposition that gender is binary and immutable and that this theory is promulgated by a group of students. This view is even more widespread among the public. A 2022–2023 survey by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) found that 65 percent of Americans believe there are only two genders. A Pew Research Center survey around the same time showed that 60 percent of Americans believed that a person’s gender should align with the sex assigned at birth. The 2025 AP-NORC poll reported that approximately two-thirds of US adults agree with the statement, attributed to Donald Trump, that gender is determined by biological sex at birth. The proportion of the population who believes this is on the rise. This is because of the work of this platform and other courageous voices.

Let’s make the professor queer for this example and imagine that he espouses the theory of gender identity. Suppose further that the official position of the university is that it is a welcoming environment for LGBTQIA+ individuals. Does this change anything? It’s hard to imagine that it does. Yes, there will be students who believe in the gender binary. The conservative and classically liberal students will for sure (whatever they stand on other matters, conservatives and classical liberals are clear-headed on this one).

Are such students unwelcome at a public university because they believe in the gender binary? On what grounds can conservatives and classical liberals be excluded from a college education or expelled from the university because of their beliefs? However, conservatives in particular at my institution tell me they feel unwelcome. Few major in my program for this reason. Many more don’t attend public universities. But, for those who come, the university must allow them to matriculate. They’re citizens—and taxpayers. And they are our future.

What do I tell my conservative students? Don’t leave. If a professor says something you disagree with, challenge him. I will have your back.

What if it were the students who believed in the gender binary drafted and circulated a petition to expel the queer professor from the university because they disagreed with his belief in gender identity? What university administration would recognize such a petition as carrying any weight at all? None, I am confident. Nor should they be. It’s not difficult to imagine that the dean of students might call the students into his office and remind them of the importance of the values of academic freedom and a free, opening, and questioning society.

Just because conservative students disagree with the professor is no reason to seek his dismissal. In America, people are allowed to believe different things. To be sure, they have the right to assemble and petition the administration, but their desire to see the professor kicked to the curb is out of step with the ideals of the public university. The petition should not only carry no weight, but it is a stain on the reputations of the students who brought it.

Now, suppose the students who circulate the petition are progressive students who believe in gender identity, and the target of their petition is a professor who believes in the gender binary and its immutability. Now things are likely to become different. The administration does not bring the students into their offices and explain to them the values of a free and open society and the vital importance of academic freedom. The professor’s colleagues don’t support their colleague but instead subject him to an hour-long struggle session, shaming him for his beliefs, wondering what they’re supposed to tell their students about him, while dressing the petition signed by those who appeals to offense-taking and safety in the robes of civic action, actions designed to chill the air and damage the reputation of their colleague.

Imagine the professor is coming up for post-tenure review. In his course evaluations, instead of providing constructive advice about his teaching, some respondents abuse the opportunity to attack him for his views, demanding he be fired. They’re thinking that his colleagues and administrators will read those comments and carry out their will—those such comments presume.

Given the situation, can we blame the professor for being concerned that the university might carry out the will of the group of students who are using these various avenues to secure his dismissal by using the post-tenure process as a proxy for punishing the professor for his belief in the gender binary?

This is what we mean when we talk about the chill. The professor knows such tactics are effective because he sees the lay of the land, as any rational person would. He knows that ideology undermines fairness and reason in ideologically-captured institutions.

Had these comments been made by conservative students in a campaign to silence and remove from employ a queer professor, complaining about things he had written on his platform, even for things he said in class (professors feel safe in presenting queer theory as obvious truth), appealing to the petition they circulated—nobody seriously thinks the professor should worry about his colleagues and administrators chastising him in a struggle session, or worrying that the post-tenure review process might serve as a proxy for punishing the professor for his belief in queer theory? Not in the least. Nor should he worry. The conservative students are in the wrong.

Why the double standard?

Put aside the guff about power asymmetries. The theory supposing an oppressor and the oppressed, and the judgment that asymmetries gives the latter the power to silence the former, is a cracked theory. It is bereft of reason. It is an entirely artbitrary proposition imposed by those with illegimate power. To be sure, one may appeal to cracked theories, but it cannot determine the fate of individuals in a civilization founded on liberty.

That nobody thinks that a university would abandon a queer professor but would be unsurprised when it kicks a liberal professor to the curb for his commitment to science testifies to how the institution has become ideologically captured by this and other progressive agendas, conscripted, if you will, into carrying out the demand that the ideology of some students be carried out in action—to wit, that belief in the gender binary should be condemned as bigoted and that professors who hold these views be censured or expelled, or at least hassled.

I close with the frame provided by Hans Christian Andersen’s parable “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” What is happening at our universities under the thumb of gender ideology is the persecution of professors for professing scientific truths. We also see this with critical race theory (CRT). The professor targeted by students committed to gender ideology is also a likely target by those committed to “antiracist” action. (For my prior use of Andersen, see Wokism and the Naked Truth; The Emperor is Naked: The Problems of Mutual Knowledge and Free Feelings; Stepping into Oppression.)

The point is that being called to account these days in public universities only occurs when their pronouncements contradict woke progressive ideology. The demand that professors uphold a particular ideology by not criticizing it occurs because, only by preventing mutual knowledge around the truth that men who say they are women are not really women, or that systemic racism is largely mythic, can the fiction that they are or can be, or that America is a profoundly racist country, be preserved. When myths crumble under the force of truth, actions lose their cloak of justice. What is left is obvious illegitimacy. This is why the public sees neo-Nazis not as a social movement but a gang of thugs.

Perpetuating the fiction is what lies behind the demand for affirmation, wrong-gender pronouns, and all the rest of the woke demands. That those around the trans identifying man correctly gender the man reminds him that he is not the gender he wishes to be (for whatever reason). The truth stresses him. If you tell a man who thinks he is God that he is merely mortal, then you will distress him. Especially if the world around the man tells him he is a woman or God.

Manufacturing and entrenching illusions takes a lot of effort, but illusions are always fragile, because they are just that: illusions. To avoid the feelings that come with crumbling illusions, the deluded man demands even more loudly that others misgender him, and if they don’t, in the camera obscura of his ideology, where things are their opposites, he accuses them of “misgendering” him. (See The Faux-Left and the Woke Function; Inverting the Inversions of the Camera Obscura; Manipulating Reality by Manipulating Words.)

Such an offense has for years been practically an unpardonable sin. We’re told that pronouns are no big deal, it’s such a little thing, but then make a big deal over them when the rules aren’t followed. But whose rules? The rules by which humans have operated for millennia? The rules that come with the instinct of natural history? Or the rules of a new minority that demands conformity to a new ideology?

It is particularly helpful to those imposing new rules that the institutions and organizations in which they move demand that everybody follow the new rules. It’s understandable that those who call the new rules into question make those who require the rules to feel unsafe. Truth threatens chicanery. Only treasonous magicians expose the tricks of the trade. Tricks depend on audiences prepared for deception. Trusting magicians with truth begins the end of civilizations.

Every professor who reads this essay knows the new rules and the pressure to follow them. Some embrace the new rules for reputational and professional advancement, even convincing themselves that the new rules are the right rules. Once so disposed, it is nearly impossible to blast them out of their cracked worldview. As the muckracker Upton Sinclair put it: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

Trepidation at violating the new rules is thus palpable. But there are other professors and graduate students who talk about the situation in hushed voices at professional conferences. They’re talking about the emperor and they don’t want the emperor to hear them. They thank me in private DMs for my courage to write posts like this and apologize for not speaking up themselves. I don’t blame them. They see what happened to me (and there are far more serious cases than mine). Yes, the imagined professor in the third scenario is yours truly (see The Snitchy Dolls Return).

Open and free spaces are unsafe because they allow the truth to be spoken and for mutual knowledge to be manifest. These spaces should be unsafe in the sense that the woke have articulated. For if we are forced to appreciate—because some people want to appear hip and smart—the emperor’s new clothes when there are none (or even when the emperor is dressed in false reality, for that matter), then we live in an unfree society. We must feel free to tell the truth. That free feeling is obtained when nobody is told what to say or punished for saying what they’re told they’re not supposed to.

* * *

A brief historical note: Sinclair was a committed socialist. He joined the Socialist Party of America in the early 1900s, ran for political office several times on its ticket, and believed capitalism exploited workers as a fact of its logic. His novel The Jungle (1906) was meant to stir outrage at labor conditions and push the public toward socialism. Instead, his exposé ended up mainly inspiring food safety reforms. For this reason, socialists were often considered part of the progressive movement in the sense of advocating reform, fighting corruption, and supporting labor rights. But Sinclair’s standpoint went well beyond mainstream progressivism, which usually sought to regulate capitalism, not replace it. Sinclair’s muckraking was coopted by elites to make corporate capitalism appear concerned with the average person. This why progressivism appears and history—and persists to this very day.