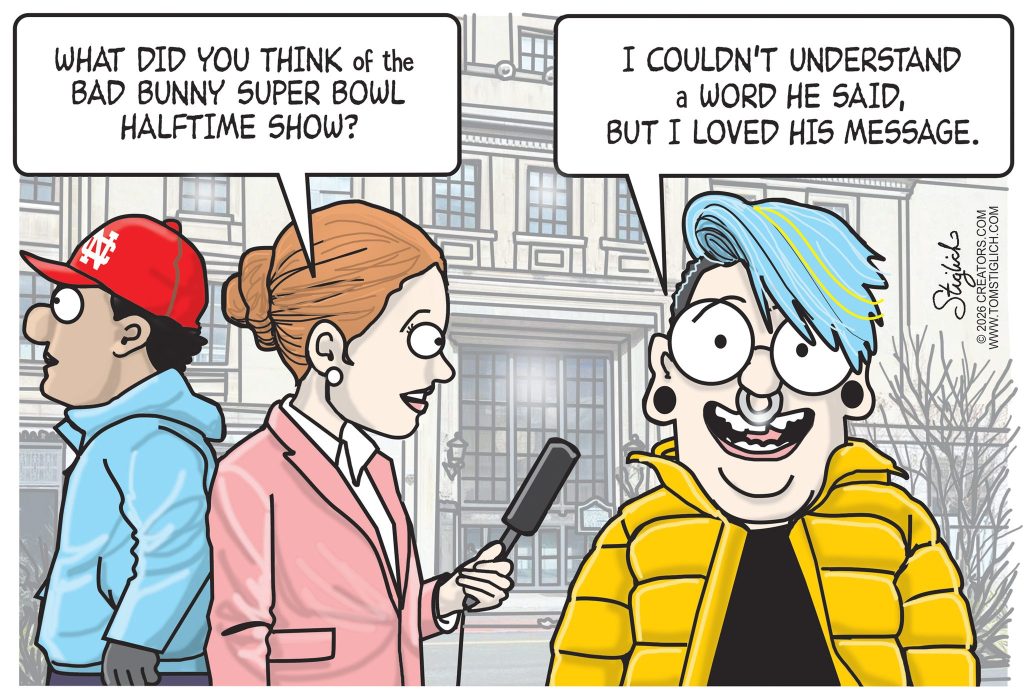

The Congressman from Florida’s 6th Congressional District, Randy Fine, an observant Jew, has triggered Islamophiles—and even some virtue signalling conservatives (Megyn Kelly, for example)—with a post defending dogs in the face of the Islamist takeover of the West. In Islam, dogs are “unclean.” There is a debate about whether this is obvious in the doctrine; however, it is a widespread belief among Muslims. Practically speaking, when Muslims run the world, the relationship between man and canine will be fundamentally altered.

Islamophiles are portraying Fine’s post as a call for genocide. This is an absurd characterization, which I will come to in a moment. But what allows progressives to portray his post in this way is by omitting context, which is typical of how the enemies of freedom operate, and the false belief that Muslims represent an ethnic or racial group, a falsehood suggested by the propaganda construction of “Islamophobia.”

For context, Fine is responding to a post by the pro-Palestinian activist Nerdeen Kiswani.

Where do Muslims get this idea? According to the Hadith, particularly in the writings of Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim, among other things, angels do not enter a house with a dog. The only purpose of dogs permitted in Islamic belief is herding and hunting. Even here, to keep a dog in the house is unclean. The naïve might soothe themselves by noting that Muslims are not in command of Western democracies. But New York City just elected an Islamist to be its mayor, Zohran Mandami. And Sadiq Khan of the Labour Party has been the Mayor of London since May 2016. These won’t be democracies if this trend is allowed to continue.

To return to Fine’s post, I want to illustrate by way of analogy why the congressman’s post cannot be a call for genocide. But before I get to that, what is genocide? Genocide, as originally conceived by Polish-Jewish lawyer and jurist Raphael Lemkin in 1944, referred to the deliberate and coordinated destruction of a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group, not only through mass killing but also through actions aimed at eliminating the group’s existence as a social and cultural entity.

Lemkin combined the Greek word genos (race or tribe) and the Latin -cide (killing) to describe a process that could include physical extermination, prevention of births, forced transfer of children, and the destruction of cultural, economic, and political institutions. His concept emphasized intent—the purposeful effort to destroy a group, in whole or in part—and influenced the legal definition later adopted by the United Nations in the 1948 Genocide Convention, which formalized genocide as an international crime.

However, Lemkin’s definition is too expansive. Lemkin’s original concept included not only mass killing but also cultural, social, and economic destruction—what he called “cultural genocide.” If genocide includes destroying identity, institutions, language, or traditions without physically killing a group, the term overlaps with assimilation and colonization, which dilutes its meaning and, furthermore, condemns nation-building as a serious human rights abuse. Under this definition, nations based on individualism and universal human rights can be falsely portrayed as oppressive projects and delegitimized or punished on that basis. The common trope on the left that the West is genocidal is the consequence of Lemkin’s expansive definition.

At the time of the legal adoption of Lemkin’s definition in international law, the United Nations intentionally narrowed genocide to specific acts committed with the intent to destroy national, ethnic, racial, or religious groups. However, even this definition is too expansive, since it arbitrarily elevates religion as a special form of ideology without any rational basis for doing so. Belief in a god or gods makes religion no different from an ideology that promotes any other potentially pernicious notion. The same is true for nationalist movements based on ideas that are destructive in practice. I hasten to emphasize that not all religions or nationalist movements are harmful. But some are, and the survival of freedom depends on our recognizing this fact.

Consider religious systems that advocate genital mutilation to mark individuals as members of a tribe. Male circumcision in the Islamic systems is widely permitted in the West. However, some Islamic cultures mutilate the genitalia of females. This is generally not permitted in the West. The tolerance of one and not the other makes no rational sense since both types of circumstances damage the genitalia and alter their function. To be sure, prohibiting either does not destroy a religious group in the UN’s narrowing of Lemkin’s definition, but a more expansive definition can argue that erasing a chief marker of a religious group erases that group in part.

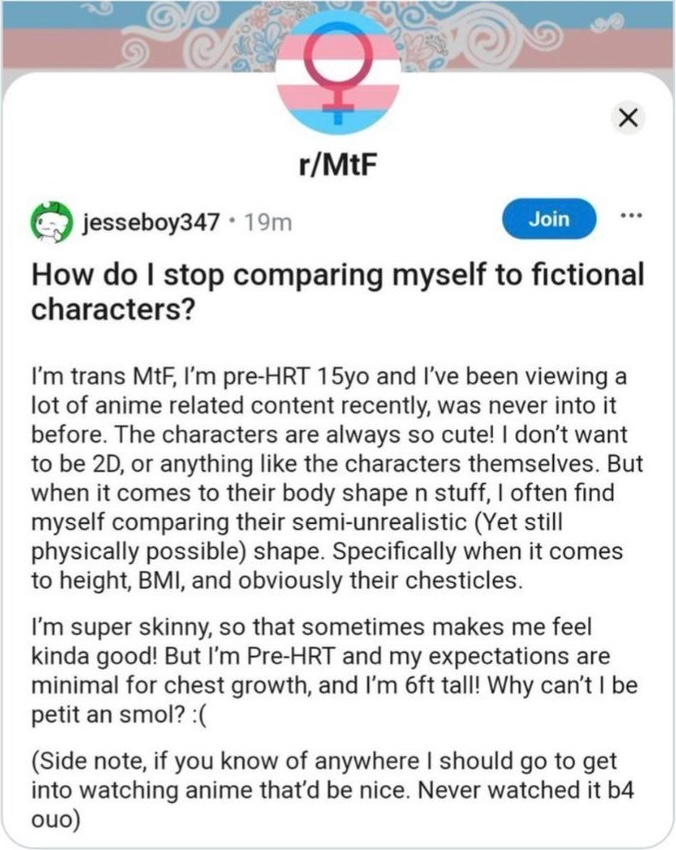

This is also true for other ideologies that are not rationally different from religions that practice gender mutilation. Gender identity disorder is the obvious analogue. Here, based on the quasi-religious belief that a girl can be born in a boy’s body, the queer tribe is declared erased when the practice of genital mutilation is prohibited. Indeed, this is the language used by trans activists in defending the practice of genital mutilation, found in the rhetoric of “trans genocide.” (See Mamdani, DSA, and Child Mutilation; Trans Day of Vengeance Cancelled Due to Genocide.)

The existence of nationalist ideology that is potentially destructive in practice is also relevant here. As with the genocidal desire of Hamas to wipe the Jews from the face of the planet, National Socialism seeks the erasure of Jews from the planet, not by wishing the end of the Jewish religion (as the atheist Karl Marx did in his wish that all religion would end, which necessarily includes Judaism), but by wishing the end of Jews as an ethnicity or race. Crucially, wishing the end of Islam rationally precludes the wish to erase those who subscribe to Islam since Muslims are neither an ethnic group nor a race.

As I have argued in previous essays (see, e.g., Corporatism and Islam: The Twin Towers of Totalitarianism), Muslims are analogous to Nazis, i.e., a group of people who subscribe to an ideology. The problem of National Socialism makes Nazism a useful analogue to explore the problem I address in this essay. The world saw no problem in the denazification of Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War. To conceive denazification as genocide is absurd on its face. The analogy is particularly apt since Islam is doctrinally highly similar to National Socialism. Indeed, it is clerical fascism with genocidal intent. It is, for all intents and purposes, the thing itself. (See Jew-Hatred in the Arab-Muslim World: An Ancient and Persistent Hatred; Why the Israel-Gaza War Is Not Seen Like World War II—and What That Reveals About the Present Situation; The Danger of Missing the Point: Historical Analogies and the Israel-Gaza Conflict.)

That a world without Nazism would be a better world is a common moral intuition. However, we shouldn’t avoid recognizing that the claim raises a philosophical question: Does expressing such a view amount to endorsing harm against people, or is it a legitimate moral condemnation of an ideology and a desire that the ideology should disappear from the earth, or at least be prohibited from acquiring political power? A careful argument shows that rejecting Nazism targets a system of beliefs and political practices, not the inherent worth of persons, and therefore does rise to the threshold of genocidal intent. Such an argument illustrates the inherent problem with Lemkin’s definition.

Nazism—historically institutionalized by the National Socialist German Workers’ Party—was not merely a set of private opinions. It was a comprehensive political ideology that justified aggressive war, authoritarian rule, racial hierarchy, and state-sponsored persecution of ethnic groups. The ideology’s consequences were not accidental; they followed from core doctrines about political authority (anti-democratic and illiberal) and race. To judge that a world without such an ideology would be better is therefore to make a moral evaluation about the content of the ideology and its practical outcomes: fewer justifications for state violence against minorities, fewer wars of aggression, and a prohibition against ethnic and racial persecution.

The philosophical distinction at stake is between condemning beliefs and condemning persons. Beliefs and ideologies are contingent; people acquire them through upbringing, persuasion, propaganda, and social conditions. All these are changeable. At least in a free society (apostasy in Islam warrants the death penalty), persons who once held extremist views may later reject them. To oppose an ideology—and this includes religion—is thus to oppose a framework of ideas, not to deny the humanity of those who hold them. Indeed, if beliefs can change, then the moral response to harmful ideologies often involves education, lawful restrictions, persuasion, and social pressure, such as ridicule and shaming, rather than violence against individuals as a first resort. Assimilation is thus a powerful tool in the arsenal against the spread of pernicious cultural and religious practices.

This distinction protects a basic moral principle: from the view of universal human rights, individuals possess moral standing independent of their political commitments. Liberal democratic traditions, in particular, hold that even those with repugnant views remain persons under the law. Denazification does not erase individuals who subscribe to National Socialism; it erases or marginalizes National Socialism. The same is true with resistance to Islamization. The Muslim as a person is not erased with the erasure of his ideological beliefs.

Punishment or restriction is justified not only when people commit crimes or incite violence, but when their ideological practices threaten the survival of a nation. Opposition to Nazism or Islam is not merely manifest because people hold objectionable opinions; rather, opposition is to these opinions in action or the potential for their manifestation in practice. Therefore, rejecting Nazism as an ideology is compatible with recognizing the rights of individuals and opposing extrajudicial harm, as well as defending a population—including those who may be conscripted in the ideology or who wish to escape it—from the possibility of the ideology becoming manifest in action. Because both Nazism and Islam are ideologies, and moreover highly similar, the same must be true with respect to Islam. To argue otherwise is to engage in the fallacy of special pleading.

We find here a practical tension. Some ideologies actively aim to dismantle the rights and freedoms of others. This is true for both Nazism and Islam. Allowing movements that seek violent domination or exclusion threatens the stability of pluralistic societies. This raises the question of how tolerant a society should be toward intolerant movements, which I have explored in previous essays (see Revisiting the Paradox of Tolerating Intolerance—The Occasion: The Election of Zohran Mamdani; Defensive Intolerance: Confronting the Existential Threat of Enlightenment’s Antithesis). I conclude in those essays that, while individuals must retain rights, societies may legitimately resist or legally constrain movements that advocate or organize violence, because tolerating such movements risks greater harm. (See Trump and the Battle for Western Civilization.)

Saying that a world without Nazis would be better need not be a call for violence against those who subscribe to National Socialism or Islam (which I oppose); it can instead express the hope that such destructive ideologies lose their appeal, fail to spread, or are replaced by more humane philosophical and political visions, and manifest that hope in assimilation and the other methods I have identified above. The ethical task is not to eliminate persons but to reduce the influence of ideas that historically have produced immense suffering. In short, condemning Nazism and Islam—the wish that these systems either did not exist or are only held by a few who are kept from power—is a moral judgment about an ideology’s consequences, not a denial of human dignity. A world without destructive political doctrines would ideally arise not through persecution, but through the gradual triumph of education, institutions, and social norms that make such doctrines unnecessary and unattractive. However, when faced with existential threats, the resort to coercion must remain on the table.

This is the point of Randy Fine’s post. Wrenched from context, and with the assumption that Muslims are analogous to an ethnic, national, or racial group, a false claim is socialized that defending the West from pernicious ideologies constitutes genocide. Nothing could be further from the truth. The condemnation of Fine’s preference for dogs over Islam is an attempt to entrench tolerance for a pernicious ideology that seeks the erasure of democracy and freedom.