This essay, which concerns the emotional and psychological burden that attends the Dunning-Kruger effect, continues my ongoing examination of cognitive errors and the rise of mental illness in America, especially among young Americans on the left. Before I get to the substance of today’s offering, I want to briefly review past writings on these matters.

I write about cognitive dissonance and motivated reasoning in various essays. See, e.g., Living with Difficult Truths is Hard. How to Avoid the Error of Cognitive Dissonance; Why People Resist Reason: Understanding Belief, Bias, and Self-Deception; When Thinking Becomes Unthinkable: Motivated Reasoning and the Memory Hole; The Fainting Man: What Kennedy and Trump Were Doing. I first wrote about the problem of cognitive dissonance back in 2007 in Cognitive Dissonance and Its Resolutions to frame a critique of Mike Adams, a conservative criminal justice professor who was treated poorly by the University of North Carolina Wilmington. By 2020, the university had pressured Adams into early retirement. Shortly afterwards, Adams committed suicide.

I have written numerous essays on personality disorders, which the DSM classifies as Cluster B. I have explored how these function at the individual level and at scale. See, e.g., Explaining the Rise in Mental Illness in the West; Understanding Antifa: Eric Hoffer, the True Believer, and the Footsoldiers of the Authoritarian Left; Chaos, Crisis, Control—Narcissistic Collapse at Scale; Concentrated Crazy: A Note on the Prevalence of Cluster B Personality Disorder; RDS and the Demand for Affirmation; Living at the Borderline—You are Free to Repeat After Me; From Delusion to Illusion: Transitioning Disordered Personalities into Valid Identities. I have also explored mass psychogenic illness in several essays: The Future of a Delusion: Mass Formation Psychosis and the Fetish of Corporate Statism; A Fact-Proof Screen: Black Lives Matter and Hoffer’s True Believer; Why Aren’t We Talking More About Social Contagion?

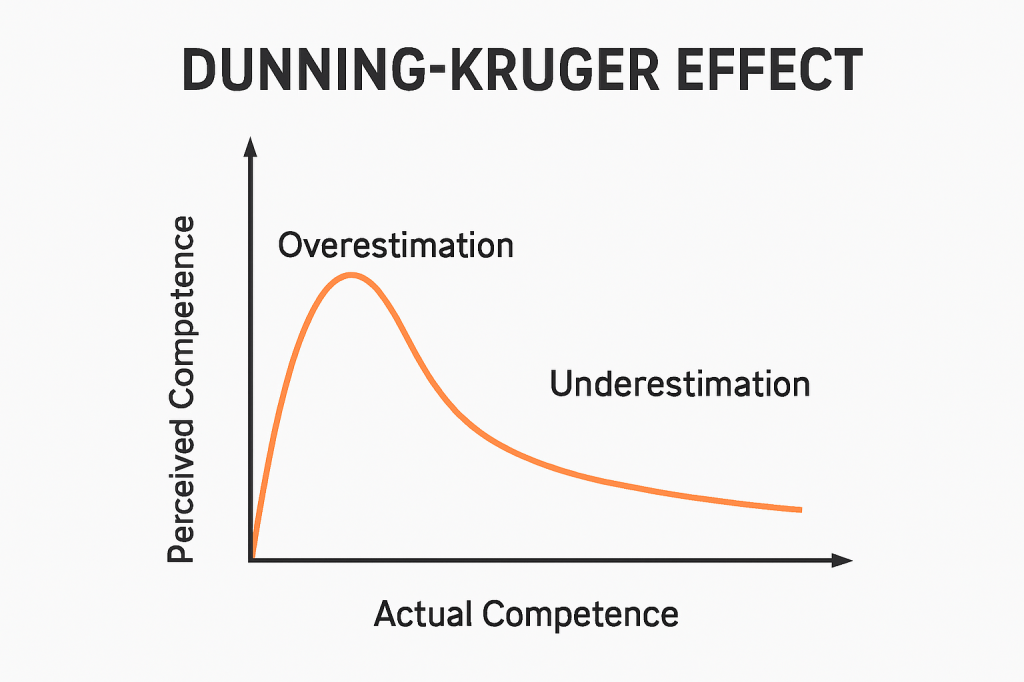

Now I turn to the Dunning–Kruger effect, first identified by social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger in 1999 in an article in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. The authors describe a cognitive bias in which individuals with low ability or knowledge in a given domain overestimate their competence. A corollary of this effect is that those with greater ability sometimes underestimate their competence; competent individuals assume their understanding is incomplete and that knowledge production requires openness and skepticism. As a consequence, those who know the least about a subject are at the same time the least equipped to perceive their own ignorance. Dunning and Kruger describe this as a “double burden” of incompetence and unawareness. For those with fragile egos, this is an unpleasant spot to be in.

Empirical support for the effect Dunning and Kruger describe is found in experiments conducted across several domains, including logic and, interestingly, humor. In the realm of civil and rational argumentation, this is often seen in the penchant among confident but otherwise ignorant persons to engage in sophistry rather than reason (in extreme cases, harassment, intimidation, and even violence). Subsequent research has replicated similar findings in fields such as academic achievement and political knowledge. (To begin one’s journey through the literature, one may go here, here, and here. The latter source may be of some help to teachers who encounter this effect and its attendant psychological burden in their students.)

Thus, beyond its original formulation as an error of metacognition, the Dunning–Kruger effect points to deeper psychological and social dynamics. When people overestimate their understanding of the world, they often do so not merely out of ignorance, but out of a need to maintain a positive and stable self-concept in the face of ego threats. They’re triggered by those they perceive as being smarter than they are. This reaction is likely when there is an ideological or political disagreement, and the afflicted wishes to believe his opponent did not arrive at his conclusions rationally. To presume otherwise might lead to an examination of one’s own beliefs, which he is stubbornly committed to for tribal reasons.

Those with fragile egos are especially upset when the person they looked up to demonstrates openness by changing his opinion on an article of faith associated with several other articles perceived to be constituents of a unified ideological worldview. Here, acknowledging that one is wrong about one thing exposes him to the threatening possibility of being wrong about a great many things, including what is perceived as the core assumption holding the standpoint together. This is why fragile egos are so rigid in their thinking (Eric Hoffer captures this trait in his True Believers).

Epistemic overconfidence, that is, the overestimation of one’s grasp of complex biological or social realities, leads individuals who hold strong but poorly informed opinions to dismiss or resent experts and, more broadly, those whom they suspect are smarter than they are across many domains, evidenced by the fact that they have accomplished more professionally and demonstrate a proficiency in applying knowledge and method to other areas. Whatever one thinks of academics with advanced degrees, obtaining those degrees and publishing in peer-reviewed journals indicates that, for the most part, they can think through problems carefully and avoid arriving at conclusions without sufficient evidence, which, gatekeeping aside, the publication of their findings and the appeal to those findings by other scholars attests to. However much the fragile ego might disagree with the conclusions of a scholar’s work, he is still confronted with the quality of mind he does not himself possess—and he resents this. The defensiveness of those who belittle and downgrade demonstrated proficiency in knowledge production serves a psychological function: it preserves the illusion of competence in the face of evidence to the contrary.

Such emotional factors as envy and jealousy thus mark the psychological burdens of insecurity. This is painfully obvious to those who encounter such persons, but not always fully recognized by those afflicted by it, and they keep that recognition at bay by lashing out at those they perceive as their antagonists—their betters—those whose existence reminds them of their incompetence.

An important piece of this is the penchant among shallow thinkers to engage in social comparison, noted in 1954 by Leon Festinger, best known for his theory of cognitive dissonance (a not-unrelated phenomenon). Festinger posits that many individuals assess their own worth by comparing themselves to others. Following from this, when an individual with a fragile ego perceives another person as more knowledgeable or insightful, even if unconsciously, it threatens his distorted sense of self. To protect against this threat, his mind generates feelings of contempt and resentment toward the more competent individual. Such a reaction acts as a psychological buffer, transforming admiration—which would require humility, absent in the narcissist (which I’m coming to)—into hostility, which is an attempt to reclaim or preserve ego integrity.

This mixture of insecurity and resentment often evolves into a fixation. A person who subconsciously recognizes his inferiority in understanding becomes preoccupied with the individual who exposes that gap. The result is an obsession—part envy, part hostility, part dependence. The dependence piece is crucial, as this is the persistent source of compulsion to ruminate over the situation. The individual revolves around the target of his resentment. He may seek to discredit the more knowledgeable person, undermine his authority, prove him wrong (albeit with no substance), or humiliate him, typically by projecting his insecurity onto the target of his emotional pain, all while seeking validation from him. He wants to get a rise out of the person because of a pathological need to be acknowledged. Submerged in his ontological insecurity, he desperately wants to have an effect against which to check his significance.

Psychologically, this pattern aligns with what is known as narcissistic vulnerability (which is not divorced from grandiosity)—a fragile form of self-esteem that vacillates between feelings of shame and superiority. The vulnerable narcissist is highly defensive, prone to envy, and frequently interprets the accomplishments of others as threats to his own self-worth. This defensiveness serves a protective psychological function, helping to preserve an illusion of competence and maintain a positive self-concept in the face of failure and self-doubt about his own adequacy.

His dismissal of, or resentment towards, those he perceives as more accomplished and smarter than him often leads him to engage in passive-aggressive behavior to shield his fragile self-image while lashing out. He feels the need to belittle the target of his envy, but instead of engaging openly with him, since he knows or fears that he cannot compete, the passive-aggressive engages in indirect expressions of hostility. Instead of directly stating disagreement, he expresses his angst through covert action. One sees this in anonymous letter writing or, more conveniently, social media accounts with obscure names, used to follow and harass those who are smarter than they are on the sly. Such persons are often afraid of publicly revealing their identity, since this would also reveal that they lack the smarts they so desperately wish they had. Thus, the effect becomes intertwined with defense mechanisms that protect the sufferer against the pain of public recognition (which is outsized in his mind). The pattern is not merely one of individual delusion but social friction—an elevation of self-assured ignorance that moves behind the many opportunities to disguise one’s identity made possible by a highly technological world.

Therefore, the Dunning–Kruger effect is not only a statement about cognitive error but, more importantly, I think, also about emotional fragility and the human need to preserve self-worth without corresponding accomplishment. I want to be careful about attributing this to human nature generally, though. The need is felt not by everyone, but by those who deep down know they are inadequate but cannot, because of their narcissism, acknowledge or defer to those who aren’t. While its empirical form describes an error of judgment (and some of the literature on this front is obnoxious in its obsession with rationalizing appeal to the authority of consensus and expertise), its deeper significance lies in how people emotionally respond to their own ignorance and insecurities to the uncomfortable presence of those who do, in fact, understand the world better, and thus remind them of their own inadequacies.

At its most profound level, then, the effect reveals the tension between ego and humility—that is, the difficulty of admitting what one does not know, and the emotional burden of encountering those who do. It would be one thing if they suffered privately, but those suffering from fragile egos sometimes burden others with their self-loathing. At that point, the effect becomes pathological, and clinical intervention is indicated.