“Because the thinking person does not need to inflict rage upon himself, he does not wish to inflict it on others. The happiness that dawns in the eye of the thinking person is the happiness of humanity. The universal tendency of oppression is opposed to thought as such”—Theodor Adorno (1969)

This essay was a long time coming. I had promised several years ago that I would tackle the correspondence between Theodor Adorno and Herbert Marcuse, both major figures in critical theory (of the Frankfurt School variety). The correspondence (which you can read here) occurred in late 1960s and highlighted the two’s divergent views on the student protest movements sweeping Europe and the US at the time, particularly in 1968–1969. Their disagreement is relevant for understanding Marcuse’s ideas about free speech and tolerance, which I write about in a 2018 essay published on the Project Censored platform, and how these have come to rationalize the repressive intolerance of woke progressivism.

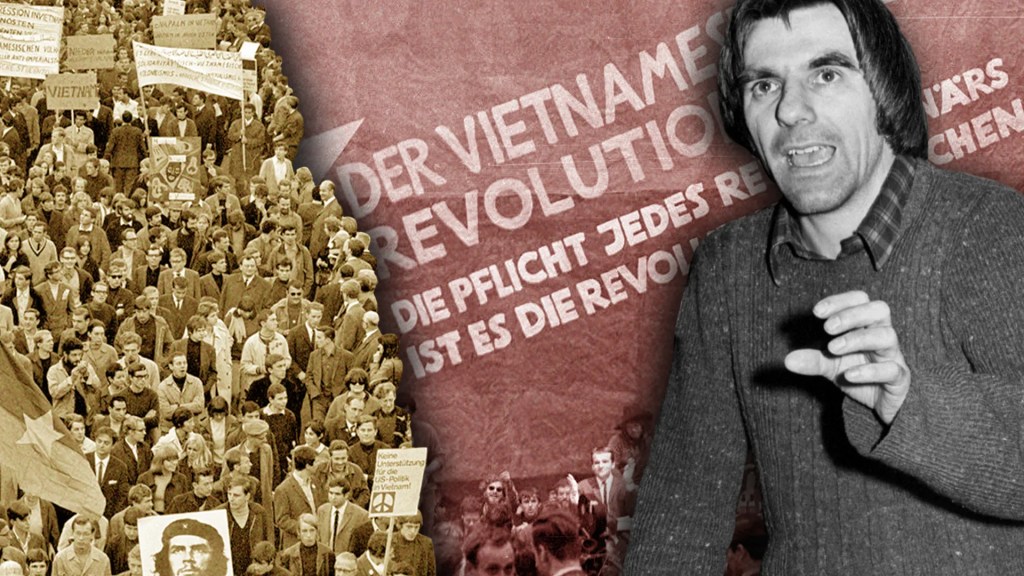

Adorno, who was based in Frankfurt at the time, took a dim view of the student protests of his day, especially those led by the German SDS (Socialist German Student Union). He saw their tactics—disruptive demonstrations, occupations of university spaces, and violence, highly resembling the recent disturbances on college campuses in Europe and the United States over the last several years—as reckless and, crucially potentially authoritarian. (For an analysis of today’s student radicalism see The Growing Threat on Our College Campuses.)

Adorno held a deep-seated wariness of mass movements, informed by the rise of National Socialism, which he’d witnessed firsthand before fleeing Germany in the 1930s. In early 1969, when students occupied the Institute for Social Research (where Adorno served as director), he called the police to clear them out. He action shocked the radical left. They thought the move was reactionary and illustrative of his detached persona. In his letters to Marcuse, Adorno justified his action by arguing that the students’ militancy threatened to undermine the enlightenment project.

Adorno was not alone in this concern. By this time, Jürgen Habermas, who was initially supportive of student radicalism, had become critical of the movement’s tactics, especially under leaders such as Rudi Dutschke of the SDS (I wrote about Dutschke recently). At a congress in Hanover in June 1967, Habermas famously clashed with Dutschke, warning that the students’ flirtation with direct action and utopian rhetoric risked what he called “left fascism.” (Habermas reflects on his position in a collection of essays published as Toward a Rational Society: Student Protest, Science, and Politics.) Habermas was with Adorno when the latter called the police.

Marcuse, living in California and more attuned to the 1960s counterculture, was far more enthusiastic of the students’ tactics. He saw the movement as a revolutionary force. In his correspondence with Adorno, Marcuse defended the students’ tactics, seeing these as a necessary break from the oppressive structures he would criticize in his 1964 One-Dimensional Man. He urged Adorno to see the protests as a practical extension of their shared critical theory.

Marcuse’s views on the violent tactics of the student movement were consonant with his views on free speech and tolerance, most notably articulated in his 1965 essay “Repressive Tolerance,” which I criticized in the Project Censored essay. Marcuse argued that a society claiming to be tolerant—i.e., the liberal democracies—perpetuated injustice by tolerating oppressive ideas (e.g., fascism, racism) under the guise of neutrality.

Marcuse proposed a radical alternative: “liberating tolerance,” which meant intolerance toward movements or ideologies that (in which view) upheld domination, while amplifying marginalized voices. This idea became the basis of the praxis of woke progressivism, seen more recently in the rise of cancel culture. What his argument amounted to was a rejection of free speech, with Marcuse suggesting that certain ideas—those he deemed regressive—shouldn’t be allowed a platform. Thus, he supported censoring far-right groups while protecting leftist dissent, a stance that smacked of hypocrisy or authoritarianism.

Prior to Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter, we witnessed social media platforms employing Marcuse’s sentiments—censoring, de-boosting, deplatforming, and shadow-banning rightwing voices. Moreover, as I argue in my 2021 essay The Noisy and Destructive Children of Herbert Marcuse, Marcuse’s justification for suppressing speech his politics deemed oppressive was enthusiastically taken up by postmodernist movements, such as Black Lives Matter and trans activism.

In their correspondence, Adorno pushed back. He warned Marcuse that his position flirted with the same dogmatic tendencies they’d both critiqued in totalitarian regimes. For Adorno, the core of critical theory was unrelenting questioning of everything, which precluded selective silencing, even if the target was intolerance itself. It is clear in reading Adorno’s words that he would not in principle support a position in which either he or anybody else served as commissar. It was against his very being as a free thinker—a being he desired for everybody else.

Their exchange peaked in 1969, with Marcuse accusing Adorno of betraying revolutionary potential by siding with the establishment, evidenced by his calling the police to remove students who had occupied the institute he directed. For his part, Adorno found Marcuse’s romanticizing the student protest as abandoning reason to chaos. History has vindicated Adorno’s position. Marcuse’s “tolerating intolerance” became a major justification for cancel culture, deplatforming, and otherwise limiting open discourse. Marcuse’s position is a paradox. And while identifying and contemplating contradiction lie at the heart of critical theory, paradox is anathema to it.