I wrote this essay April 27, 2022 and never hit publish. I found it buried in the cue searching for something else and, after some light editing, I am publishing it today. I have neither added nor subtracted any of its original content. I have since written numerous related articles elaborating this thesis, but there are some unique elements to this essay, and it represents the foundation of my arguments since.

The threat I identified in the spring of 2022 has been mitigated somewhat, not only with the reelection of Donald Trump, but the success of the populist movement across the Western world. But progressivism is still the operating system and moral pretense of the corporate state. The election of Trump, as well as a Republican Party more reflective of the general will, is only the beginning of the People’s campaign to deconstruct government by administrative rule and the Deep State that protects it. This essay, written at the midpoint of the simulation of a presidential term (the Biden-Harris regime), will thus serve as a marker of the New Dark Ages we are just now escaping. My hope is that these words will motivate my fellow populists to stay focused and engaged.

* * *

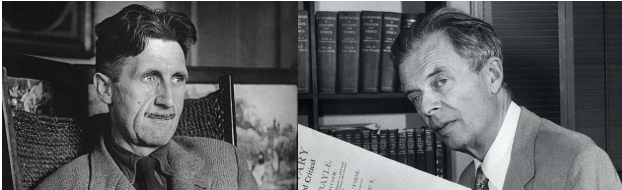

“Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.” —George Orwell, “Why I Write” (1946)

As readers of Freedom and Reason know, I have long subscribed to the theory of regulatory capture, which the CFA Institute succinctly defines as “a phenomenon that occurs when a regulatory agency that is created to act in the public interest instead advances the commercial or political concerns of special interest groups that dominate an industry or sector the agency is charged with regulating.” But the more I learn about the history of progressivism, the more I am convinced that our regulatory agencies were never really independent bodies created to act in the public interests but rather were always the instruments of corporate power and its search for legitimacy in a system to which it stands as the antithesis. These agencies have in any case functioned to thwart popular control over local concern and stifle mass democratic action.

As I will show in this essay, it is no coincidence that progressivism and the regulatory system to which it gives voice appear with the establishment of corporate personhood, which, in the United States, entitles business firms to First, Fourth, and Fourteenth Amendment protections, a development occurring in the late eighteenth and early twentieth centuries. What were before privileges granted by government—then corporations were considered “artificial persons” subject to writs of quo warranto, whether sought by king or citizen—became the same rights as those to which actual flesh and blood persons were entitled, while the privilege of capital remained exclusive to the firm. Under the governance of the corporate person, the sovereign people, the republican citizen, became once more a subject.

The regulatory system is thus an integral part of what Richard Grossman, founder of the Program on Corporations, Law, and Democracy, calls the “corporate state,” the power that now towers over the republic, turning its legal and political machinery, the legitimate gears of justice, into the powerful instruments of tyranny. Regulation is not, as advertised, the “spirit of reform,” but a strategy the power elite deploys to humanize exploitation while, by dividing and disorganizing the masses upon which advocates for the interests of the common man depend for the success of their democratic work, draining social activism of its power. Regulation is one weapon the progressive wields to block and dissipate populist desire. The citizen demands his right to determine the conditions of his existence in a free society; the corporate state denies his right and returns him to serfdom.

Seeing how the left has been, for the most part, sucked into the vortex of progressive praxis, the center of gravity of the gathering populist storm is the political right. This is a transformative historical moment with which we must engage; the political right has swung around to working class interests and politics, challenging the corporatist establishment even of the Republican Party (and threatening to take that party back to its roots in labor). That establishment is controlled by the same power that controls the Democratic Party, and is marked by the same ideologies, namely neoliberalism and neoconservatism. The rank-and-file political left in the United States, and in Canada and Europe, as well, is aligned with the professional-managerial strata that controls the education system, the culture industry, the legacy and social media, and runs the administrative state. Comprising the populist forces are working people and small businesses.

The validity of left-right divisioning of political power has thus been cast in serious doubt. “Left” and “right” are becoming legacy terms once describing the habit of the liberal and radical political parties to sit to the left of the presiding officer’s chair, while those representing the nobles and the clergy, the true conservative parties, sat to his right. It’s an old story. The left was comprised of the bourgeoisie and the laboring masses seeking transformation of the social order. The right sought to preserve the traditional order of things. As time passed, the democratic republican form was accepted by both sides, conservatives and liberals (the former moving towards the latter) became more alike, and the socialist ambitions of the proletarian masses emerged as a threat to both. All this occurred in the context of bourgeois civil society and the juridical-political frame of the modern nation-state.

In both the Ancien Régime and, until recently (in historical terms), the new liberal order, the corporation was answerable to the sovereign. By what authority could a corporation behave in such a manner as to contradict the interests of the sovereign? But then the corporate state was established and the political jargon of left and right was mapped onto the new hyper-rational structure, and the party of the slaveocracy, of the feudal-like arrangements of the plantation system, the Democratic Party, insinuated itself into the political left, while the populist Republicans, the party of small “d” democracy and limited government and all that entails for liberty, the party that was founded by abolitionists and socialists, became identified with the political right. Corporate power and its technocracy, enabled by Democrats, advanced the progressive movement. This essay concerns this history.

Before moving to that, I need to say this: The character of our politics—for those of us who believe in the values of autonomy and individualism—is populist nationalism, which includes classical liberalism and, to a major extent, modern conservatism, versus progressive globalism, the antithesis of leftwing praxis. That progressivism produces results similar to those seen in state socialist and bureaucratic collectivist arrangements that go under various names (corporatism, fascism, national socialism, socialism with Chinese characteristics) is in part evidence of convergent societal evolution. But it is also the work of transnationalists. (See Why I am not a Progressive; China Represents the Existential Threat of our Time—and the Democratic Party is a Chief Enabler; Mao Zedong Thought and the New Left Corruption of Emancipatory Politics; Physical Capital, Human Capital, Technology, and Productive Work—These Drive the Real Economy; The New Left’s War on Imaginary Structures of Oppression in Order to Hide the Real Ones.)

George Orwell, a democratic socialist, was right to name the totalitarian nightmare world of Airstrip One “Ingsoc,” New Speak for English socialism, which abandoned the tradition of English common law and instead took after Stalin’s Russia. Aldous Huxley before him was right to describe his dystopian World State as standing on the foundation of the bureaucratic-rationalist principles of consumerism, homogeneity, mass production, predictability, and uniformity. Christopher Hitchens succinctly noted the difference between these fictional accounts: the former was a house of horrors; the latter, hedonistic nihilism. But both were destructive to human freedom—and they are coming together in the New World Order.

Populist nationalism is a movement to save the world from all that and deepen the foundation of Western civilization—and that means subordinating corporate power to the sovereign, which is today the citizen of modernity. The progressive globalist, in contrast, wants to tear down the West for corporate power and reduce citizens to serfs in a neofeudalist world order. Progressive globalism is a real-world work of synthesis—of Orwell and Huxley. Its vision, concrete history of much of the last century, is anti-Enlightenment, anti-human, postmodern. (see Global Neo-Feudalism: Backwards to the Future; George Soros, Philanthrocapitalism, and the Coming Era of Global Neo-Feudalism.)

Thus there is a confusion of terms. Oftentimes populism gets mixed up or conflated with progressivism. Because of this mixup, I hear complaints from liberals that the original ideas of progressivism have been betrayed. Sometimes liberals, self-identifying of course, even condemn liberalism for betraying them (see The Democratic Party is Not the Party of Liberal Politics; The Problem of the Weakly Principled). But progressivism and liberalism aren’t the same things and progressivism has always been what it is (just as liberalism has). Progressivism has always been regulatory and transnationalist in orientation. And now, in full ascendency, it is in many ways the New Fascism.

* * *

What is the history of this madness masquerading as progress and reason? Progressivism was established as a system of population management in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The two principle targets were workers and consumers. Progressive government is designed to prevent the proletariat from developing class consciousness and rising up against industrial capitalism and concentrated financial power by assuming the worker into efficiency regimes and methods of legal and extralegal social control. For example, progressives pushed alcohol prohibition to sober up workers and keep them home at night to make them more productive for the capitalist class, generate more surplus value for the realization of profit in the market, the products with which they would be seduced to buy with their meager wages. Before alcohol prohibition, there was sharp regulation of narcotics to control populations under the guise of public health. And afterwards, when prohibition of alcohol was ended in the 1930s, modern drug prohibition was rolled out under the progressive regime of Franklin Roosevelt with the control of cannabis.

The history of industrialism is one in which the capitalist class, in fundamental ways, has waged war with human nature. In his Prison Notebooks, building on Max Weber’s analysis of bureaucratic corporate rationalization, Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci writes, “In America, rationalization has determined the need to elaborate a new type of man suited to the new type of work and productive process.” Industrialism is “a continuing struggle against the ’animality’ in man.” The goal is to transform man, which involves “psycho-physical adaptation to the new industrial structure.” “It has been an uninterrupted, often painful and bloody process of subjugating natural (i.e. animal and primitive) instincts to new, more complex and rigid norms and habits of order,” Gramsci continues. “exactitude and precision which can make possible the increasingly complex forms of collective life which are the necessary consequence of industrial development.” Gramsci tells us that the process is “developing in the world to the highest degree automatic and mechanical attitudes, breaking up the old psycho-physical nexus of qualified professional work, which demands a certain active participation of intelligence, fantasy and initiative on the part of the worker, and reducing productive operations exclusively to the mechanical, physical aspect.”

This is the cybernetic function Weber describes in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (written 1904-1905). “Military discipline is the ideal model for the modern capitalist factory,” writes Weber. “Organizational discipline in the factory has a completely rational basis. With the help of suitable methods of measurement, the optimum profitability of the individual worker is calculated like that of any material means of production. On this basis, the American system of ‘scientific management’ triumphantly proceeds with its rational conditioning and training of work performances, thus drawing the ultimate conclusions from the mechanization and discipline of the plant. The psycho-physical apparatus of man is completely adjusted to the demands of the outer world, the tools, the machines—in short, it is functionalized, and the individual is robbed of his natural rhythm as determined by his organism; in line with the demands of the work procedure, he is attuned to a new rhythm though the functional specialization of muscles and through the creation of an optimal economy of physical effort. This whole process of rationalization, in the factory as elsewhere, and especially in the bureaucratic state machine, parallels the centralization of the material implements of organization in the hands of the master. Thus, discipline inexorably takes over ever larger areas as the satisfaction of political and economic needs is increasingly rationalized. This universal phenomenon more and more restricts the importance of charisma and of individually differentiated conduct.”

Because this program is contrary to nature, the control must necessarily be an external imposition and therefore coercive. At least at first. The goal is to make new habits “second nature,” Gramsci contends. When coercion is exercised over society, puritanical ideologies develop as external form of persuasion and consent to the intrinsic use of force. Masses acquire the customs and habits necessary for new systems of living and working or are subject to coercive pressure through elementary necessities of existence.

For Weber, this is what disenchants the world and threatens to destroy individually differentiated conduct, a concept that captures both freedom and individualism. “Since asceticism undertook to remodel the world and to work out its ideals in the world,” Weber writes, “material goods have gained an increasing and finally an inexorable power over the lives of men as at no previous period in history. Today the spirit of religious asceticism—whether finally, who knows?—has escaped from the cage. But victorious capitalism, since it rests on mechanical foundations, needs its support no longer. The rosy blush of its laughing heir, the enlightenment, seems also to be irretrievably fading, and the idea of duty in one’s calling prowls about in our lives like the ghost of dead religious beliefs. Where the fulfillment of the calling cannot directly be related to the highest spiritual and cultural values, or when, on the other hand, it need not be felt simply as economic compulsion, the individual generally abandons the attempt to justify it at all. In the field of its highest development, in the United States, the pursuit of wealth, stripped of its religious and ethical meaning, tends to become associated with purely mundane passions, which often actually give it the character of sport.”

Rationalization of work and prohibition thus become inevitably connected in establishing the worker’s second nature. This included, and these persist, inquiries conducted by industrialists into workers’ private lives (surveillance) and the inspection services created by firms to control the “morality” of workers are necessities of new methods of work. As Frederick Taylor, the founder of scientific management, “expressed with brutal cynicism—the purpose of American society” was to develop “trained gorillas.” “There was a need for worker to spend their money rationally to maintain, renew, and, if possible, increase muscular-nervous efficiency and not to corrode or destroy the body.” Regulating drugs (and potentially many other things) becomes a function of the corporate state. Gramsci writes, “It is in [the capitalists’] interests to have a stable, skilled labor force, a permanently well adjusted complex, because the human complex (the collective worker) of an enterprise is also a machine which cannot, without considerable loss, be taken to pieces too often and renewed with single new parts.”

The corporate collectivist regime also included sexual controls. “The new type of man demanded by rationalization of production could be developed until sexual instinct had been suitably regulated and rationalized,” writes Gramsci. “The new methods of control and production demanded rigorous discipline of sexual instincts—a strengthening of the ‘family’ and regulation of sexual relations.” One might think that under capitalism, the exchange of money and sex would seen as just another market transaction. But in the corporate system, control over the most intimate activities of the working class required regulation. Hence prostitution becomes criminalized, justified by various rhetorics, religious and secular.

Gramsci, aping the propaganda of progressives in their attempt to revise the history of America writes, that “Americanization requires a particular environment, a particular social structure and a certain type of state. The state is a liberal state in the sense of free-trade liberalism or of effective political liberty, but in the more fundamental sense of free initiative and of economic individualism which, with its own means, on the level of ’civil society,’ through historical development, itself arrives as a regime of industrial concentration and monopoly.” He is describing progressivism.

As much as we must fight for liberal values, the economic component supported by these same values is useful to a system that functions to minimize popular democratic practice. In some aspects, democracy and liberalism are not twins, but for the most part opposites, that must exist in tandem and tension. In his essay “Peace, Stability, and Legitimacy” (1994), Immanuel Wallerstein puts the matter in a pessimistic way: “Liberalism was invented to counter democracy. The problem that gave birth to liberalism was how to contain the dangerous classes. The liberal solution was to grant limited access to political power and limited sharing of the economic surplus-value, both at levels that would not threaten the process of the ceaseless accumulation of capital and the state-system that sustains it.” Wallerstein here is obsessing over the capitalist relations piece the liberal order justifies, but he is on to something and we must pay attention to it, especially in capitalism’s late stage of corporate statism. However, the problem in overcoming the restrictions on speech and conscience that exclusive control over the means of production portend involves establishing democratic practices that realize core liberal principles for everybody while negating the illiberal tendency inherent in the majoritarian impulse.

“It is from this point of view,” Gramsci continues, “that one should study the ’puritanical’ initiative of American industrialists like Ford. It is certain that they are not concerned with the ’humanity’ or the ’spirituality’ of the worker, which are immediately smashed. This ’humanity and spirituality’ cannot be realized except in the world of production and work and in productive ’creation.’ They exist most in the artisan, in the ’demiurge,’ when the worker’s personality was reflected whole in the object created and when the link between art and labor was still very strong. But it is precisely against this “humanism’ that the new industrialism is fighting.”

Recall that, in Huxley’s Brave New World, the industrialist Henry Ford becomes a Christ-like figure. One finds citizens of the World State substituting for “God,” Ford’s name; where one would hear “the Year of our Lord,” one hears instead “the Year of our Ford.” It is not, as conservatives suppose, that we have seen a diminishment of the religious impulse amid industrialization. Finke and Stark show in The Churching of America the way in which the rise of religiosity in the United States in the nineteenth century, not at all prominent at its founding, made possible the marshaling of faith commitments in developing the control systems that marked the emergence of large-scaled industrialization. Industrialization generalizes the Protestant Ethic—which was always a projection of the capitalist spirit.

The trans-humanist desire this movement inspires was such that, during this period and for some time after (until Hitler embarrassed the other western nations with his racial nationalism driving the thought and practice underground), progressives pushed eugenics to engineer superior human stock for the same purposes as they sought to control the body. They also stood up the technocratic system of public health, pushing quarantine and vaccination, using the latter as precedent to justify forced sterilization. They even used the newly established penitentiary and reformatory system as mechanisms of preventative incapacitation to prevent the promulgation of deplorables. It was the progressives who pushed for state control over bodies and set up the regulatory agencies that greased the path to corporate governance. Progressives established regulatory agencies—the FDA, USDA, etc.—in order to legitimize capitalist practices in production and in consumer markets.

Progressivism is racist not just in the scientistic practice of eugenics. It is also racist in its advocacy for the institution of racial segregation. Progressive Democrat president Woodrow Wilson, the 28th president of the United States (1913-1921), segregated the White House upon assuming office. At the same time, in what may appear to be contradictory, Horace Kallen and urban cosmopolitan ilk jettisoned the “melting pot” for the “salad bowl” metaphor, juxtaposing cultural pluralism in opposition to assimilationism. They also advanced the goal of trans-nationalism. —All this back in the 1910s-20s. Cultural pluralism was used to prevent immigrants from integrating with American values and developing nationalistic attitudes.

Later, in a corporatist move, Roosevelt pulled labor under industry by legalizing labor unions and pulling labor’s fangs. It was under his regime, as Richard Grossman points out, that progressivism was institutionalized. The progressives, in control of the central cities, segregated blacks in the ghettos during the Great Migration and established open borders on the 1960s that made black labor redundant. They created the custodial state to manage black idleness. They engineered globalization that, along with the welfare state, has devastated black families.

The fact is that progressives have always been on the side of big industry, big finance, and the professional-managerial class—the credentialed class—that works the administrative state and the culture industry. They’re behind the lockdowns, passports, mandates, etc, a continuation of the corporate state power that marked eugenics (which they still work—just check and see where Planned Parenthood tends to work—and then check and see what Margaret Sanger believed). And if systemic racism exists at all, then progressive Democrats own it. They were the party of slaveocracy, the party of Jim Crow, and now the party of diversity, equity, and inclusion, the new colorful brand of racism. To be sure, the Civil Rights movement dragged progressives kicking and screaming into equality. But they deftly replaced civil rights with identity politics, using their control of culture and education to turn the narrative on its head.

* * *

The arguments I make on Freedom and Reason are rooted in well-established sociological thought, as well as thinking across disciplines, including anthropology, communications, legal studies, political science, and psychology. I encourage readers to study Max Weber’s analysis of the corporate bureaucracy and its rationalizing effects, what he depicts as a freedom-destroying “iron cage”—or, perhaps a better translation from the German, “steel casing”—surrounding the person. Readers should also consult the work of Antonio Gramsci, which provides an analysis of suffocating force of bureaucratic rationalism, part of a set of observations that landed him in prison under the corporatist regime of Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini. Crucial to these arguments are the control strategies popularly known as Fordism and Taylorism—automation, mechanization, task specialization, deskilling, and scientific management.

The Frankfurt School scholars, especially Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, separately and in collaboration, carried forward this line of thinking in a unique way, synthesizing Weber’s insights with those of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. In the United States, C. Wright Mills and his analysis of the power elite and the military-industrial complex, indebted to Frankfurt scholar Franz Neumann, moves is in this vein. These thinkers examined state monopoly capitalism and corporate governance and the extinguishing of human freedom and creativity under national socialism and the post-Nazi periods. See also the development of mass persuasion, marketing, and public relations. Edward Bernays and Walter Lippmann represent the tip of the spear in this field. There is a large body of literature here. See Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent and Chomsky’s 1988 CBC Massey Lectures (collected as Necessary Illusions). See also the work of Robert W. McChesney.

There are many other important lines of research I can cite here, but this essay has gotten long, so I want to conclude by describing the actual sociopolitical space in which we make our lives.

As I noted at the beginning of this essay, it is becoming increasing clear, to me at least, that progressivism did not develop to regulate capitalist production in a manner benefiting the general public, but rather to facilitate capitalist accumulation, which includes the transformation of the culture (including the moral order), law, and the state in order to expand and entrench the power and control of economic elites. Crucially, then, the innovation of regulation, similar to social welfare, is chiefly concerned with establishing the hegemony of the capitalist mode of production.

Academics, big industry, financial elites, cultural and media persuaders, and subservient politicians have always been behind multiculturalism (cultural pluralism) and globalism (transnationalism), core elements of progressive thought. This thought has recently become “woke.” Woke indicates awareness of and the practice of being actively attentive to the alleged existence of various injustices and oppressions, especially concerning claims about the situations of racial and gender identities. Woke progressivism, which has captured all of the West’s major institutions, is a secular religion, a quasi-religion if you will, that developed within the professional managerial class (or strata), emerging with rise of industrial capitalism and the corporatization of economic and social life. The duty of this religious-like ideology (and my conception of ideology includes practice) is to advance the interests of of the corporate class. This ideology has by and large captured the left which has led to a rapid shift in loyalties.

The Democratic Party, historically a coalition of slaveowners, and later segregationists, alongside industrial capitalists, is today the party of the corporate state. Progressivism and its attendant project of multiculturalism, is the organized political expression of these powers and ideologies. The Democrats opposed assimilationist and integrationist policies from the beginning. As soon at they were compelled to relent and end segregation in the 1960s, they passed open borders legislation and promoted globalization, elaborated a custodial state to control the industrial reserve, what President Lyndon Johnson dubbed the “Great Society,” and elaborated the ideology of cultural pluralism and selective moral relativism.

Scholars have described this situation as “embedded liberalism.” The goal was to liberalize trade while at the same time expand the social welfare state to manage the consequences of trade liberalization, i.e., an approach to economic and social dislocation pitched as a set of compassionate domestic policies confronting inequality—which grew as a result of these policy changes. This was necessary because of the fall in the rate of profit brought about in part by the strength of labor to secure compensation aligning with productivity gains while gains in productive, achieved by automation, mechanization, and globalization undermined the ability of capitalists to realize surplus value as profit in the market. These trends are not unique to the United States, but are also features of the social democracies of Europe. Is it these ideas that find their manifestation in the Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Union (EU), the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Emerging from this development is neoliberalism, an extreme market-oriented philosophy that, in addition to deregulating industry and capital markets and lowering trade barriers, progressively privatizes public functions, asserts corporate governance everywhere, and imposes conditions of austerity. The emergence of the transnational corporation and its systems is accompanied by neoconservatism, a rebranding of Cold War liberalism and internationalism (the liberal rule-based international order) focused on the full-spectrum military dominance of the United States in order to facilitate the dismantling of the interstate system and advance the interests of the nascent transnational corporate state.

Although these political and economic forces portray themselves as for the Common Man, the reality is that the Democratic Party and the progressive movement stand in opposition to the working class, the farmer, and the small and medium-sized entrepreneur, who are more liberal and democratically-minded (i.e. personal autonomy and small government), as well as emphasizing the importance of family and assimilation with American values. The attitudes of the working class, the farmer, and the entrepreneur are nationalist and populist in orientation, and so, in an Orwellian move, such attitudes are portrayed in academe, by the culture industry and the mass media, all controlled by progressives, as reactionary and even white supremacist. The progressive movement in turn pulls non-whites (except for Asians) into their coalition through pandering, resentment, and affirmative action, to stitch together a bulwark against popular challenges to power. Corporate power portrays itself as a forward-leaning pro-people movement when in truth it only pushes change where it finds opportunities to accumulate capital.

The ruling class has erected an ideological system that disguises its class interests behind a self-serving narrative. The system manufactures an at once sophisticated and faux-popular ideology that convinces a majority of working people that the interests of the rulers are the interests of everybody. It is a project of constant historical revisionism. When they need to change history, the cultural managers in their employ are more than happy to change the narrative to fit with the demands. Gramsci referred to these workers as “organic intellectuals,” whom he distinguished from “traditional intellectuals.” The latter were devoted to preserving history, advancing science as a general proposition, and other forms of knowledge. The traditional intellectual never goes away; he is, however, marginalized. The former are the functionaries of the ruling class, who now dominate our universities, news organizations, and the world of movies, publishing, etc. They are the experts and authorities and persuaders and influencers. George Orwell wasn’t writing about a possible future. He was writing in future terms about present reality.

A populist revolt is gathering. The people are pushing back. At school boards and in legislatures across the heartland. The pandemic slowed its progress but did not crush it. That’s why elites are clamping down so hard in Europe. The resistance marches are massive there. The elite can see things slipping away. Too many alternative sources of information, which elites are scrambling to contain, have the effect of producing mutual knowledge, which in turn becomes the basis of common purpose and political organizing.

The people the mainstream tells you are “conspiracy theorists,” those to whom you shouldn’t be listening, are the people you should be listening to. They’re the ones who have been getting it right. What folks said was conspiracy theory last month, is concrete fact today. The pandemic was rolled out in impressive fashion, but, because elites have lost control over informational flow, it could only fool some segments of the population and others for only so long. The anarchy of the Internet and the structure of alternative news established by populist forces have changed the character of popular knowledge production forever. I end this essay on a positive note.