I do this periodically to help people understand the underpinning of my standpoint. I do it because political thought today is organized by partisan ideological and propagandistic frameworks that confuse terminology and distort the relationships between ideas. The misuse of the word “liberal” to convey progressivism especially irks me, as regular readers of Freedom and Reason well know (and probably wish I would quit complaining). Depictions of populism and nationalism as indicating the presence of authoritarianism and racism are other examples of political-ideological distortions. So I feel the need to clarify matters now and again not only so people will understand me, but also so they will have a reasonable chance at entertaining ideas they may wish to take up and advance or at least defend. Moreover, I do it to clarify matters for myself: Freedom and Reason is a project of sharpening the resolution of my perception.

My political stance reflects a blend of democratic-republicanism, classical liberalism, populism, and nationalism—all hailing from what has traditionally been described as left wing. At its core, my standpoint values the principles of democratic self-governance and individual liberties, emphasizing the importance of a government that is accountable to the people but protective of individual and natural group rights. Examples of natural groups are gender (or sex) and family (child safeguarding, inheritance, and parental rights). These commitments align with classical liberal ideals of free markets, limited government, and personal freedom. These ideals wrapped in a secular humanist ethic focused on self-actualization. My populist inclinations express a desire that our institutions represent the interests and will of the people over again excessive elite and corporate influences that undermine democratic processes and individual liberty. I am skeptical of administrative rule, corporatist arrangements, and technocratic control.

Nationalism in my view emphasizes a strong sense of national identity and sovereignty, promoting policies that prioritize the nation’s interests and unity. More than this, it is the view that a people should be governed by the rule of law, with a common culture and language, in a state system with clear separation of powers—executive, judicial, and legislative—preventing the leveraging of the democratic machinery to establish tyrannies of the majority or the minority. It is in the context of a secular nation-states founded on constitutional republicanism (which avoids the problems of parliamentary democracy and technocracy) that we exist as citizens rather than serfs, slaves, or subjects. Together, these elements form a political philosophy that seeks to establish and perpetuate a system of government resistant to corporatist influences, ensuring that governance remains rooted in the values of equality, liberty, and popular sovereignty.

I often refer to myself as a Marxist. I recently wrote about this, but I want to restate my position because I know the term is off-putting. I describe myself as a Marxist in the social scientific sense, which expresses an adherence to Marx’s analytical framework for understanding societal structures and dynamics and historical development. Much like a Darwinist who uses Darwin’s theory to explain natural history, I utilize Marx’s theory to analyze class structures, economic systems, and social relations, as well as a critique of ideology, without necessarily endorsing the political regimes or policies that have historically claimed Marxism as their foundation. Indeed, I am highly critical of societies claiming to be founded on Marxist ideas, declaring that I am not a socialist in the pages of Freedom and Reason. The Marxist approach, which is sometimes referred to as the “materialist conception of history,” or just “historical materialism,” focuses on the critical examination of capitalism, the role of labor, and the interplay between economic base and superstructure in shaping society, while maintaining a distinction from the political implementations seen in places like Cuba or China.

My approach to Marxism offers a distinct advantage by allowing me to critique capitalism while also explaining its developments from a comprehensive analytical-theoretical framework. By utilizing Marx’s analytical framework, I can differentiate between a Marxist critique of capitalism and the realities of societies that claim to be Marxist, thereby critiquing both. This perspective enables me to highlight the incoherence of right-wing attributions of Marxism to corporatism and progressivism, arguing that these are manifestations of corporate statism rather than societies rooted in worker ownership and control over the means of production. This nuanced understanding allows for a more precise critique of contemporary capitalist societies and the various political and economic systems that arise within them.

Marxism in sociology focuses on the analysis of class struggles, and economic systems, and social relations, emphasizing how economic factors and material conditions shape societal structures and historical developments. In contrast, the Durkheimian framework, after Emile Durkheim, from which structural functionalism emerges, views society as a complex system of interrelated parts that work together to maintain stability and social order, emphasizing the importance of social norms, values, and institutions. Symbolic interactionism, stemming from the work of George Herbert Mead, centers on the subjective aspects of social life, focusing on how individuals create and interpret meanings through social interactions and how these meanings shape their actions and societal roles. The Weberian framework, derived from Max Weber’s theories, emphasizes the role of beliefs, ideas, and values in shaping social action and institutions, highlighting the importance of understanding the subjective meanings individuals attach to their actions and the influence of bureaucracy and rationalization in modern society.

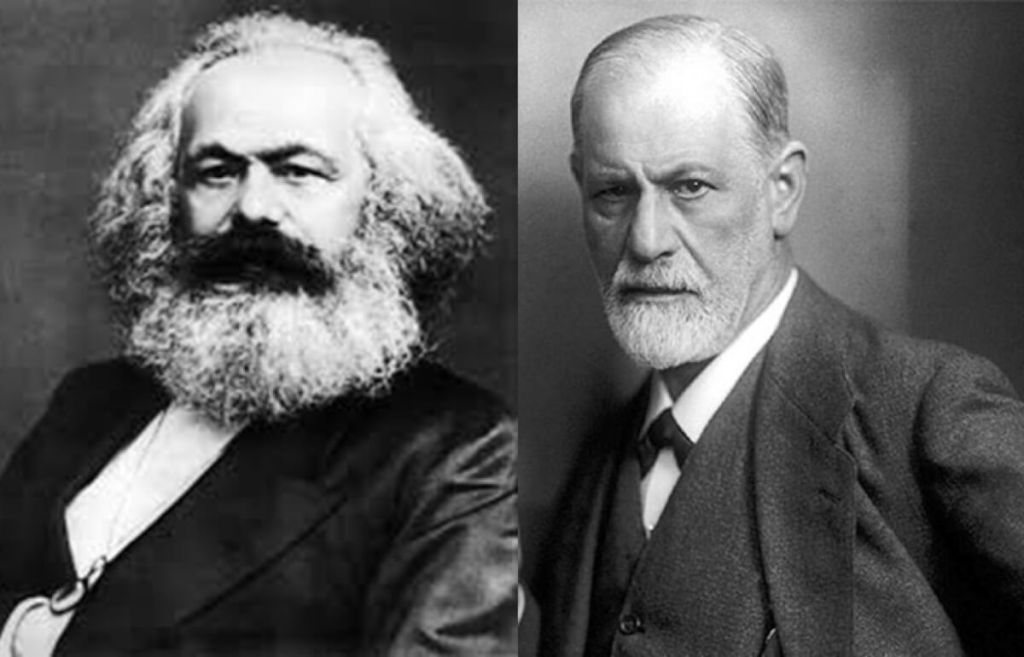

Marx’s and Sigmund Freud’s systems are similar in that both provide comprehensive frameworks for understanding human behavior and societal structures by examining underlying, often hidden forces. I would describe myself as a Freudian thinker on psychological matters (see Erich Fromm’s 1966 Marxism, Psychoanalysis and Reality). Marx’s analysis focuses on economic structures, class relations, and material conditions as the driving forces behind societal dynamics, positing that the economic base shapes the superstructure, including culture, politics, and ideology. Freud, on the other hand, delves into the psyche, exploring how unconscious conflicts and desires influence individual behavior and mental health. Both Marx and Freud emphasize the importance of uncovering these hidden forces—economic exploitation in Marx’s case, repressed desires and unconscious conflicts in Freud’s—to achieve a deeper understanding and potential liberation. Additionally, both theories suggest that individuals are often unaware of the true sources of their behavior and suffering, whether it be false consciousness in Marxism or unconscious repression in Freudian psychoanalysis.