“Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.” —George Orwell, “Why I Write” (1946)

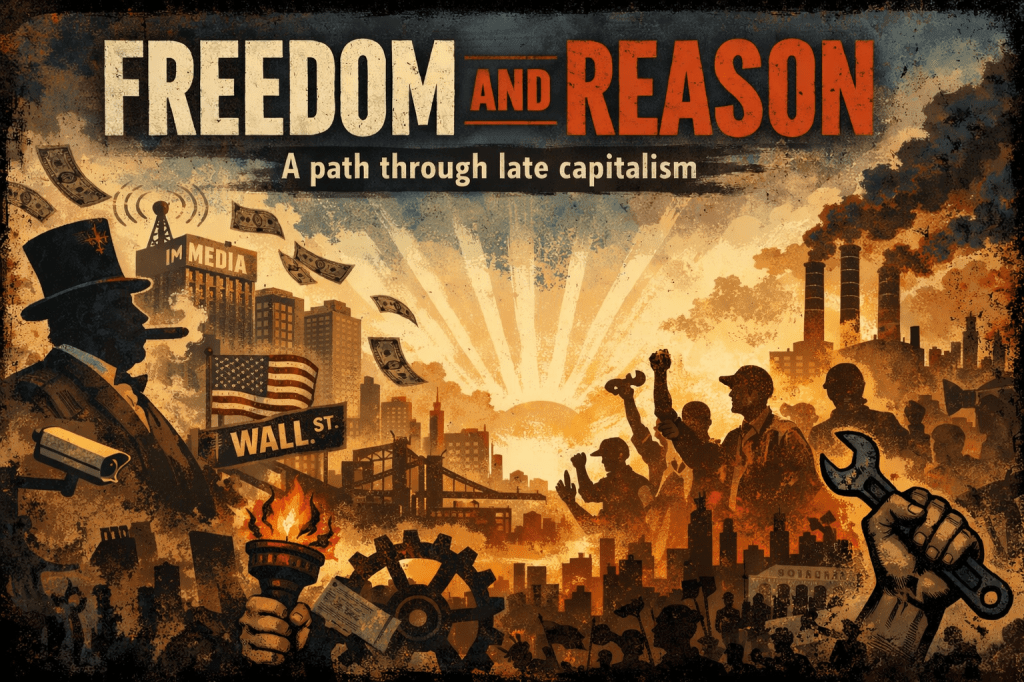

Welcome to Freedom and Reason: A Path Through Late Capitalism, or FAR. FAR is an independent platform where I share critical analyses of societal issues that are both scholarly and accessible to the public. Think of this platform as a chronicling of history with commentary.

While not affiliated with the institution that employs me (I say this to protect my exclusive copyright), this platform reflects my commitment to public sociology—engaging with a broader audience to address public issues, influence policy, and foster debate. As a salaried public employee, I work for the people.

Public sociology bridges the gap between academic knowledge and everyday concerns, democratizing insights to make them useful and actionable in addressing inequality, social justice, and other pressing social problems. I am inspired by C. Wright Mills’ idea of the “sociological imagination.”

I hold a PhD in sociology from a large public university, with expertise in criminology and political economy. I also hold a bachelor’s degree in psychology, with a minor in anthropology, and a master’s degree in sociology, where I focused on social psychology.

Originally launched on Blogger in 2006 to make my ideas available beyond the constraints of establishment academic outlets and the classroom, Freedom and Reason experienced intermittent activity due to my extensive service work and administrative duties at my institution. However, in 2018, after witnessing firsthand the migrant crisis in Sweden during a self-funded research expedition, I migrated the blog to WordPress and tasked myself with writing regularly.

This transition has allowed me to build an audience for my ideas and safeguard my work not only to establish exclusive copyright to my writings, but also from potential censorship, particularly as my views have (apparently) become increasingly controversial from the standpoint of the woke progressivism that has colonized our sense-making institutions and corrupted mass perception. Woke progressives have a closed and illiberal mindset. WordPress is a free and open system where I can provide my scholarship to readers without commercial/institutional interference or the whims of the commissar.

Since its re-platforming on WordPress, Freedom and Reason has garnered over 70,000 views from readers around the world, with thousands of annual visitors. Steadily growing since the 2020 pandemic, 2025 was the platform’s most successful. I’m thrilled that my work is being read by a diverse and global audience. While these numbers may be regarded as relatively modest, they far surpass the engagement typical of traditional academic publishing. This institution suffers from gatekeeping, ideological capture, paywalls, slow turnaround time, and small and exclusive readership.

What is more, this platform allows me to sidestep the artificial constraints and demands of formal expertise. The contemporary insistence on expertise—tightly bounded specializations legitimized through editorial descretion and peer review—has become a defining feature of academic work, but this framework is historically recent and has degraded scientific scholarship (this is why my work appears much like the scholarship produced in the nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century).

Before the mid-twentieth century, and especially before the institutionalization of professionalized peer review after the 1960s, intellectual life was far less constrained by disciplinary boundaries. Scholars frequently operated across what is now considered distinct fields, synthesizing insights from biology, economics, history, philosophy, psychology, sociology, and its sister discipline, anthropology. This broader mode of inquiry allowed observers to address large, world-historical questions and to integrate phenomena that are qualitatively emergent and irreducible to any single discipline.

Critics of specialization have long argued that the bureaucratic division of intellectual labor fragments problems that are inherently systemic. This critique was articulated forcefully by Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy in the preface to Monopoly Capital (1966), which I reference in my essays on this platform, where they lament the increasing compartmentalization of scholarship and advocate for a return to problem-focused, interdisciplinary analysis (something that I fought for at my institution, in the end having to admit defeat).

For Baran and Sweezy, specialization does not merely constrain creativity; it also obscures the interdependent dynamics—ecological, economic, psychological, sociological, etc.—necessary for understanding late capitalism as an integrated totality. Their call for a holistic social science reflects a broader mid-century anxiety that disciplinary silos were producing narrow technicians rather than thinkers capable of grappling with the structural complexities of the world, an anxiety recent history has proven well-founded.

In his 1959 The Sociological Imagination, which I allude to above, C. Wright Mills levels one of the most influential attacks against what he calls “abstracted empiricism” and the bureaucratization of social science. For Mills, the transformation of scholarship into a technical, method-driven enterprise—dominated by survey research, large organizations, and professional incentives (something with which Paul Diesing concerns himself in his 1992 How Does Social Science Work? in distinguishing between democratic and technocratic science)—threatens the very capacity of sociologists to link “private troubles” to “public issues.”

Like Baran and Sweezy, Mills sees specialization as producing intellectual technicians rather than thinkers capable of diagnosing the structural forces shaping modern society. While Baran and Sweezy focus on the political economy of monopoly capitalism, Mills focuses on sociology’s internal crisis and the broader ideological drift of American social science, as well as the broken linkages between freedom and reason (something that concerned Max Weber in his critique of rationalization), which inspired the name of this platform. Both critiques converge in their belief that meaningful analysis requires crossing disciplinary boundaries and recovering the capacity to ask “big questions.”

Finally, I would be remiss in leaving out Immanuel Wallerstein’s critique, articulated most systematically in The Modern World-System and later in his report Open the Social Sciences, which extends and systematizes the critique of disciplinary silos. Wallerstein argues that the social sciences were artificially carved into separate disciplines—economics, political science, sociology—during the nineteenth century to serve the needs of capitalist modernization and transnational corporate interests.

This division, Wallerstein contends, obscures the historical and systemic nature of the capitalist world economy. In his view, only a genuinely historical social science—what he calls “world-systems analysis”—is capable of analyzing global capitalism as an interconnected whole. In scope and tone, this position resonates strongly with Baran and Sweezy’s call for holistic political economy and a return to asking big questions. Wallerstein pushes the critique further by framing specialization as part of the ideological apparatus of the modern world-system itself.

During my career, as I have pursued the project of problem-focused interdisciplinarity around questions of late capitalism across domains, I have had my freedom to express my views in speech and publishing vigorously challenged. These attacks have come from the left and the right, but especially from the left of late, which is ironic given that political compass tests locate me on the grid denoting left libertarianism.

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution, holding that Congress shall make no low abiding the freedom of speech and of publishing, Articles 18 and 19 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the corresponding articles of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as the principle of academic freedom (which allows me to publish what, when, and where I choose), are my licenses to publish my analyses and opinions without fear of consequences from the state and public institutions.

The George Orwell quote at the top of this page, from his 1946 essay “Why I Write,” is my purpose here. I am particularly focused on continuing Orwell’s critique of totalitarianism, whether from the left or the right. I am sympathetic to Orwell’s democratic socialism, but I am not a socialist. the world’s experience with socialism has been tragic.

I moderate comments, so if you’d like to communicate with me privately, just mention that in your comment, and I won’t publish it. I appreciate all feedback, whether public or private, and if it warrants a response, then I will respond as soon as possible.

Please subscribe to Freedom and Reason and share it with others to help me reach more people with critical analyses and opinions on issues like authoritarianism, censorship, class, crime, culture, economics, gender, media, politics, race, and religion.

Thank you for visiting Freedom and Reason. I hope you find something here that resonates with you, or at least gets you thinking.

Updated 1.2.2026