Update (January 22) Willian Kelly, aka dawokefarmer, who filmed himself screaming at churchgoers after storming their church, has been arrested. Kelly was arrested just hours after he had a meltdown on TikTok where he called for people to rise up and “shut this country down.”

Update (January 22): According to reporting by The New York Times, two of the members of the mob that interrupted a church service in St. Paul, Minnesota. Nekima Levy Armstrong and Chauntyll Louisa Allen have been taken into custody by the FBI.

Is there a tension in contemporary Christian discourse between Jesus’s injunction, “Judge not, lest you be judged,” and the claim that Christianity constitutes a moral system? At first glance, these positions can appear incompatible, and they are often treated as such—especially within progressive Christian contexts, where moral judgment is displaced rather than abandoned. I will argue that progressive Christianity enforces standards grounded less in coherent ethical principles than in shifting criteria of affinity and power, both personal and collective. By contrast, within a classical framework of Christian ethics, no such tension exists.

Morality, by definition, involves judgments about how people ought to act, distinctions between good and bad behavior, and standards by which actions are evaluated. If these standards are to be universal, they must appeal to an objective ontology.

As I explained in essays at the end of last year (Moral Authority Without Foundations: Progressivism, Utilitarianism, and the Eclipse of Argument; Epistemic Foundations, Deontological Liberalism, and the Grounding of Rights), progressivism is relativist and utilitarian; as such, it eschews defining a moral ontology. In short, there is no moral substance to the woke church; there is only a rhetoric of virtue, one exuding indignation, self-righteousness, and egoism.

To be sure, the woke Christian invocation of “do not judge” can appear to function as a blanket prohibition on moral evaluation, but this reading mistakes a situational admonition for a universal forbiddance. In contemporary progressive discourse, moral judgment itself is often portrayed as inherently exclusionary, harmful, or oppressive. Taken at face value, however, this understanding departs sharply from the role judgment plays within the New Testament and within rational Christian theology more broadly. In its original context, the command to “judge not” does not abolish moral discernment—the capacity to recognize, reflect upon, and decide what is good or right in particular circumstances—but rather presupposes and disciplines it.

In the same discourse, Jesus calls out hypocrisy—appearing righteous outwardly while acting unjustly in practice; judging others harshly while denying one’s own fallibility; using religion for status rather than genuine devotion to God. In the light of Christian ethics, the progressive Christian is the antithesis of Christianity because he denies each of these sins in himself (see Standing King’s Dream on Its Head: The Nightmare Antithesis of the American Way).

On Sunday in St. Paul, Minnesota, a mob of around 40 members of Black Lives Matter Minnesota, the Racial Justice Network, and allied community leaders entered the sanctuary of Cities Church and disrupted the service. Nekima Levy Armstrong, a longtime Minneapolis attorney, self-proclaimed civil rights activist, and community organizer, as well as an ordained minister, led the intrusion. With her were other local figures—Monique Cullars-Doty (BLM Minnesota co-founder), Chauntyll Allen (St. Paul public school board member and activist), and Satara Strong-Allen (community leader)—and outsiders, former CNN host Don Lemon and combat veteran and social media influencer William Scott Kelly, who goes under the handle “DawokeFarmer.”

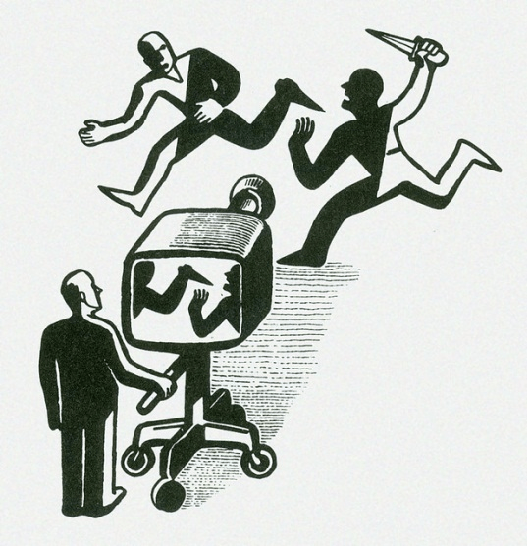

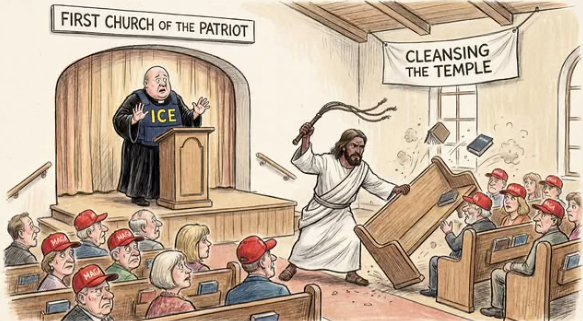

Armstrong and Lemon, in particular, reinforced by memes comparing their actions to Jesus’ purification of the temple, have claimed in interviews to represent true Christianity. Lemon was brought along to create a video record of the cleansing, so the world could see the righteousness of the mob—a feature of its madness (see The Phenomenon of Progressive Brain-Locking and Its Role in the Madness of Crowds). Desperate to be seen, Lemon took his turn atangonizing churchgoers.

This is not what they were doing. In the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus, teaching in the Jerusalem temple, which he declared to be “my Father’s house,” affirmed its sacred purpose as a place of prayer for all nations by dramatically cleansing the temple by driving out merchants, money changers, and their animals, condemning them for having turned a house of prayer into a den of thieves, which symbolized how religious authorities had distorted worship through exclusion and exploitation. Jesus’ actions helped prepare the grounds for his prosecution.

The egoism of the mob betrayed their appeal to faith. Jesus taught that religious devotion should be sincere and directed toward God rather than performed to impress others. In the Sermon on the Mount, he said, “When you pray, go into your room, close the door, and pray to your unseen Father. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you.” He contrasted this with praying publicly for show, warning against hypocrisy and empty repetition.

The crux of this teaching is that the faith the world would come to know as Christianity is about a genuine, humble relationship with God, not public display or social approval. Jesus cleansed the temple as the Son of God, not as a self-proclaimed righteous man who justified destructive and terrorizing action based on that holiness. Moreover, he instructed his followers to obey civil law—to never use their devotion to God as a license to transgress statutes of the secular authority.

Armstrong, Lemon, and Kelly not only appealed to the authority of God, but also to the United States Constitution to justify entering the sanctuary of a church and harassing the congregation as the exercise of free speech and protest action. This was the framing by The New York Times, which covered the story with the headline “Protest at Minnesota Church Service Adds to Tensions Over ICE Tactics” (transparently lamenting the possibility that BLM action might delegitimize the insurrection against the federal government).

Yet the First Amendment does not warrant harassment or trespass in a place of worship—or any other place immune from the heckler’s veto. Moreover, that amendment guarantees religious liberty. Protest is about expressing advocacy and opposition while respecting others’ rights to safety and worship. Once the goal or effect is coercion, fear, or interference, it crosses the line from protest into criminal behavior, regardless of the cause being claimed. There were children in attendance on Sunday, and Lemon’s camera captured the terror in their faces. This wasn’t a protest action; this was mob intimidation. A congregation of peaceful Christians was terrorized.

We have been here before. Across many communist revolutions in the twentieth century, independent religious institutions—especially Christian churches—were treated as inherent threats to revolutionary authority and were therefore subjected to coercion, intimidation, and suppression. Because churches represented alternative sources of communal loyalty and moral authority, they were seen as rival power centers incompatible with movement or state control. As a result, revolutionary regimes in countries such as the Soviet Union, China, Vietnam, Cuba, and across Eastern Europe routinely invaded or closed churches, harassed or imprisoned clergy, and terrorized congregants through denunciations, political reeducation, and surveillance.

The aim was not merely secularization, but the consolidation of ideological monopoly, in which moral formation, social organization, and ultimate allegiance were redirected from religious communities to the revolutionary regime itself. What we witnessed in Stl Paul on Sunday was the radical desire to replace traditional Christian authority with an authoritarian reorganization of society wrapped in a rhetoric of Christian love. The dress was see-through, the body of hate clearly visible.

Jesus also speaks of recognizing people “by their fruits.” Such a teaching presupposes the ability, indeed the necessity, to evaluate actions and character. One cannot identify hypocrisy, bad fruit, or moral failure without making judgments about action and behavior. The prohibition is not against moral reasoning itself but against a particular kind of judgment: hypocritical, self-righteous, or condemnatory judgment that assumes the prerogatives of God.

Mob intimidation by those on the left in the name of Jesus assumes the perogatives of God, transgressing the laws of a nation founded upon Christian ethics and natural law by falsely appealing to the righteousness of Christian moral authority. They demand Christian love to make themselves immune to judgment by those who love Christ.

They, moreover, appeal to Christian justice to make themselves immune to legal consequences. But when asked whether it was lawful to pay taxes to the Roman government, Jesus replied, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s,” affirming a legitimate place for civil authority, even under a pagan and unjust regime, while also observing that obedience to the state does not replace devotion to God.

Yet, in Jesus’s teaching, devotion to God is not a license to disobey civil law. His instruction to “render to Caesar what is Caesar’s” assumes compliance with lawful civil authority, even when that authority is imperfect or unjust. Jesus himself paid taxes, respected legal processes, and did not encourage resistance or lawbreaking in God’s name—a devotion to secular power necessary for crucifixion!

For Jesus, faithfulness to God expresses itself within the bounds of civil order, not outside it. For this reason, Martin Luther King, Jr., advocated peaceful civil disobedience, the legal consequences of which must be accepted by his followers (see The Rule of Law and Unlawful Protest: The Madness of Mobs).

In Christianity, God’s authority does not justify coercion, disruption of others’ rights, lawlessness, or terrorism. On the contrary: devotion to God calls for humility, peace, and respect for law. When one of Jesus’ disciples, Peter, drew a sword and cut off the ear of the high priest’s servant, Malchus, Jesus stopped him, saying, “Put your sword back into its place; for all who take the sword will perish by the sword.” He then healed the servant’s ear, demonstrating his commitment to peace and mercy, even in the face of violence.

Religious conviction is never a blanket justification for civil disobedience, and it forbids righteous violence against authority. Disobedience to the state must always be principled and grounded in Christian ethics—and a last resort. Violence, especially, is always an action of last resort. Even if we take the mob that entered Cities Church on Sunday at its word, that it was led by Christians, there is no basis in Christianity to trespass and terrorize the congregation in a religious sanctuary. Nor is there any basis to do so in the secular laws of the American Republic. On the contrary, the secular law defends religious liberty.

The secular law is clear in this case. Beyond the First Amendment, in addition to reproductive health facilities, the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act (18 USC § 248), commonly called the FACE Act, makes it a federal crime to use force, threat of force, or physical obstruction to intentionally injure, intimidate, or interfere with any person exercising their religious freedom at a place of worship. This includes entering, leaving, or participating in worship services at churches, synagogues, and mosques.

Many observers have asked us to imagine a mob of Christian Nationalists entering a mosque and intimidating the congregation. What would Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison say about that? We may soon know, as several top Minnesota political leaders have been subpoenaed by federal authorities as part of an ongoing investigation into the chaos in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

Federal prosecutors, including the Department of Justice and the FBI acting through a grand jury process, have issued subpoenas to, among others, Governor Tim Walz, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey, St. Paul Mayor Kaohly Her, and Attorney General Ellison. While these subpoenas seek documents and communications related to interference with and obstruction of federal law enforcement efforts, scrutiny of the state’s failure to charge and prosecute the Sunday mob will likely become part of the inquiry.

* * *

The modern progressive resolves the tension noted at the top of his essay not by clarifying types of judgment, but by collapsing them. Moral discernment and moral condemnation are treated as indistinguishable. To judge actions is equated with harming persons, but only for the progressive’s choice of comrades. The progressive man condemns ICE for frightening children when deporting illegal aliens (an unfortunate consequence for the choices of parents who have no right to be in America), but he claims righteousness for his own action of frightening children. Really, he does not regard children at all, but uses them either to affirm his moral character (such as it is) or as targets of his rage.

It is not the case, therefore, that the progressive operates without moral pronouncements; rather, the progressive Christian appeals to an ideological framework dressed in faith that, in truth, operates outside Christian ethics and natural law. Wokeness does not eliminate judgment; it merely redefines its grounds and redirects its energy.

This should be obvious: progressive Christian discourse issues strong moral judgments against “judgmentalism,” traditional doctrine, exclusion, and perceived harm, while, at the same time, judging others based on ideological notions—critical race theory, postcolonial theory, and queer doctrine. These notions are prettied up with the language of “kindness,” but beneath the makeup lies ravenous swine. (See The Problem of Empathy and the Pathology of “Be Kind”.)

The reality is that it is not whether judgment exists, but who is permitted to judge and be judged. Without a moral ontology, this becomes entirely arbitrary, manifested either by mob action or totalitarian command. This is the moral relativism of progressivism: the targets of judgment are not based on an objective ethical system, but on power, personal or collective. It dresses itself in the raiments of salvation and manufactures its own Christs, elevating those who obstruct and resist civil authority to the status of martyr—Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, George Floyd, and now Renee Good. The Sunday mob chanted “Hands up, don’t shoot” and, in a call and response, “Say her name!” “Renee Good!”

Classical Christianity addressed the tension coherently by distinguishing between judging actions and condemning souls, between moral correction and final judgment. Christians were called to name sin while acknowledging their own fallibility, to correct others with humility, and to leave ultimate judgment to God. This framework preserved moral clarity without claiming moral omniscience.

In the modern period, Christian ethics, emerging from rational Christianity and natural law, sources from which the Founders formed the moral order underpining the American Republic, universalizes moral judgment for every citizen, each equal before the law. Faith becomes a personal matter, while law applies to everyone, the state possessing the sole authority to enforce the law with violence where citizens fail to follow it.

The core problem, then, is not judgment itself, but confusion about its nature. This confusion is intentional. A moral system that forbids judgment cannot survive; it negates the very standards that make morality possible. Christianity remains morally intelligible only by distinguishing kinds of judgment, not by judging arbitrarily or abolishing judgment altogether. Crucially, Christian judgment can only be the law of a secular society when it is universal and detached from Christian theism (since people are free from the imposition of faith as a matter of the ethic itself).

America cannot allow mobs of left-wing activists to impose their novel and cynical interpretation of Christianity over the law or the personal rights of Christians. When that distinction is lost, an artificial vocabulary of morality emerges—“social justice”—and gives way to zealotry; and the edict to “judge not” becomes less a moral principle than a rhetorical shield against moral (and legal) accountability.

If Christians are instructed not to judge, how can Christianity meaningfully function as a moral framework at all? It can’t. Progressive Christians offer the world no moral system, for no moral system can be found in relativism or utilitarianism, where morality is whatever power says it is, or where the means are rationalized by desired ends with no moral purchase.

Indeed, progressives suck the morality out of Christian ethics, scattering the Gospels of Jesus into a jumble of cherry-picked scriptures arbitrarily selected to justify harassment, intimidation, and violence in pursuit of decadent ends. The social justice warrior leverages the name of Jesus as a cudgel to attack conservative and liberal Christians and the American Republic. It is not only un-Christian—it’s un-American.

Christianity has always been unavoidably moral. It names certain actions as sinful, calls for repentance, and demands moral transformation. Concepts such as sin, repentance, forgiveness, and redemption lose all meaning if no behavior can be judged right or wrong, or if such judgments are made in bad faith. A Christianity that forbade judgment in every sense or judged from an ideological standpoint would cease to be a moral system and collapse into moral incoherence. Such a Christianity would be no Christianity at all. And this is the Christianity to which the Sunday mob appealed. These are fake Christians.

The BLM mob can escape neither religious nor secular judgment for its actions on Sunday. Those who comprise it must be made an example for others who would cynically leverage religious faith to justify mob intimidation and collective violence. Bring the hammer.

* * *

Note: A journalist cannot claim immunity simply because he is documenting a crime. While observing or reporting on illegal activity is generally protected under free press principles and the First Amendment in the United States, these protections apply only when the journalist does not himself engage in illegal acts. If a journalist encourages, directly participates in a crime, or provides material aid, he can be prosecuted as a principal, accomplice, or accessory, even if his intent includes documenting or reporting the event. In short, the act of reporting does not shield someone from criminal liability when he actively participates in the crime itself. Don Lemon is in trouble.