Karl Marx (1818-1883) stands among the giants in the history of scientific thought, alongside such luminaries as Nicolaus Copernicus, whose 1543 On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres posits the heliocentric solar system, Isaac Newton, whose 1687 Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy establishes the foundation of classical mechanics, and Charles Darwin, whose 1859 work On the Origin of Species lays the basis for evolutionary biology.

The publication of Capital: The Critique of Political Economy, published in 1867, puts Marx in their company. In this work, Marx solves the riddle of capitalist accumulation. But that is not all. Marx’s frequent collaborator and closest friend, Friedrich Engels (1820-1895), on the occasion of Marx’s funeral in 1883, notes Marx’s significance in this way:

Just as Darwin discovered the law of development or organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history: the simple fact, hitherto concealed by an overgrowth of ideology, that mankind must first of all eat, drink, have shelter and clothing, before it can pursue politics, science, art, religion, etc.; that therefore the production of the immediate material means, and consequently the degree of economic development attained by a given people or during a given epoch, form the foundation upon which the state institutions, the legal conceptions, art, and even the ideas on religion, of the people concerned have been evolved, and in the light of which they must, therefore, be explained, instead of vice versa, as had hitherto been the case.

Marx also discovered the special law of motion governing the present-day capitalist mode of production, and the bourgeois society that this mode of production has created. The discovery of surplus value suddenly threw light on the problem, in trying to solve which all previous investigations, of both bourgeois economists and socialist critics, had been groping in the dark.

Science was for Marx a historically dynamic, revolutionary force…. For Marx was, before all else, a revolutionist. His real mission in life was to contribute, in one way or another, to the overthrow of capitalist society and of the state institutions which it had brought into being, to contribute to the liberation of the modern proletariat, which he was the first to make conscious of its own position and its needs, conscious of the conditions of its emancipation.

Marx’s contribution to the world of ideas, as well as to the practical every-day struggles for social justice, is relevant for today’s fight for democracy. Marx developed a comprehensive method for theorizing historical change and societal development, what he and Engels called the “materialist conception of history,” or “historical materialism.” This essay concerns the development of Marx’s scientific method of historical and scientific study, which synthesizes critiques of classical liberal political economy and the continental idealist theory of history. The goal of this work is to empower working people to fight for socialism.

Socialism’s opposite, liberalism, dominates our politics and legal system such that it shapes even our understanding of democracy, identifying “liberal democracy” (more liberal than democratic) as the only type of democracy consistent with individual freedom. The alchemy of liberalism ideologically transmutes democracy into majoritarianism (tyranny of the majority), a practice destructive to human rights. It then, rightly, if such a thing were true, condemns it. But it is not true. Marx, taking up the critique of liberalism by German philosopher Georg Hegel, provides a radically different standpoint, identifying socialism and communism as containing the true promise of democracy. This may seem paradoxical to those unfamiliar with Marxian thinking, but my hope is that you will at least be able to develop an appreciation for the argument by the end of this essay.

Crucially, Marx’s system transcends the “is-ought” dichotomy that pervades Western thinking about the character of knowledge, a dichotomy that, by demanding a strict separation between what “is,” that is, knowledge considered “objectively” true (and here objectivity is confused with neutrality and value-free science), and what “ought” to be (subjective matters of political opinion or moral judgment), functions to marginalize those who believe that knowledge about the social world should be used to advance the interests of the oppressed and downtrodden. Conflating “is” and “ought,” Marx explicitly wields knowledge as a weapon for working people against their exploiters.

I begin with Marx’s definitive statement of his method. In the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, published in 1859, Marx writes:

The first work which I undertook to dispel the doubts assailing me was a critical re-examination of the Hegelian philosophy of law; the introduction to this work being published in the Deutsch-Franzosische Jahrbucherissued in Paris in 1844. My inquiry led me to the conclusion that neither legal relations nor political forms could be comprehended whether by themselves or on the basis of a so-called general development of the human mind, but that on the contrary they originate in the material conditions of life, the totality of which Hegel, following the example of English and French thinkers of the eighteenth century, embraces within the term “civil society”; that the anatomy of this civil society, however, has to be sought in political economy.

There is a lot to unpack in this paragraph. Let’s begin with political economy. In his Second Treatise on Government, written in the latter seventeenth century, John Locke argues that persons own themselves and therefore own their labor—and, by extension, own the products of their labor. This notion of personal sovereignty is a central tenet in liberalism. By mixing one’s labor with nature, Locke claims, the person creates property. Because it is a natural extension of the individual, he therefore has a natural right to it. For Locke, property relations are the basis of the social contract. Government exists to protect the natural right of property.

Locke’s philosophical and ethical position, on the one hand, and his political practice, which strived to secure private control over the property produced by others, and even the accumulation of persons as property, on the other hand, illustrates a contradiction in liberalism: if the products of labor naturally belong to those who labored to produce them, then why do those who labor give them up to others who profit from them without expending any or very little labor? Marx sought to make people aware of this contradiction and to realize liberalism’s promise by establishing socialist freedom.

Writing in the second half of the eighteenth century, in The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith was suspicious the idea that the exchange value of a commodity depends on its utility or usefulness, its “use-value.” Commodities instead exchanged on the basis of the amount of labor expended in producing them. Smith distinguished between “nominal value,” the amount one would exchange for a commodity, and “real value” or “natural price,” the amount of labor embodied in a commodity (Marx deals with this issue at some length in Capital). Writing in the early nineteenth century, David Ricardo theorized that the amount of labor embodied in a commodity determined its equilibrium price. In other words, production costs, of which labor is ultimately the root, determined the average price of commodities.

The Wealth of Nations is concerned to show how raising the wealth of a nation benefits the nation as a whole. This was the basis of his advocacy for capitalism and free trade over the mercantilism that prevailed during his day. In his political economic work, Smith voices two concerns: (1) revealing the force that holds society together and (2) revealing the force that transforms society over time. He conceives of the market—a self-regulating mechanism—as that force. Smith argues the following points: The market transmutes chaotic self-interest into social harmony—it turns anarchy into order. The market empowers consumers to dictate the kinds and quantities of commodities the industrialists will produce. The market has a tendency towards equilibrium, regulating prices and incomes. The market interacts with the division of labor to produce innovation—the source of social evolution. Good ideas are selected by the system and perpetuated, spreading throughout the system. Bad ideas go extinct. All this acts as an invisible hand, a force that operates independent of human intention. Smith’s theory of a natural economic bears more than a passing resemblance to Darwin’s theory of natural selection. In fact, Darwin admitted that the work of Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, and Herbert Spencer inspired the logic of his evolutionary model. Here’s the rub: by treating the market as a self-regulating phenomenon, Smith means to create the appearance of economics as a natural phenomenon, one that lies outside of, or at least should (laissez faire), lie outside of the control of human agency. This puts political economy beyond democratic politics. It transmutes subjection to the mercy of economic forces into a definition of liberty.

Marx incorporates many of Smith’s ideas; however, he does not do so uncritically. He shows that each of these processes Smith identifies functions not to raise the wealth of the nation in terms of making the general population better off, but rather to raise the wealth of a few while impoverishing and subordinating the many. He shows that the system did not peacefully emerge from the natural differentiation in human attitudes, capabilities, and dispositions, but was the result of the bloody expropriation of the commons, dispossessing humanity of free access to the means with which to make their way through life. And, crucially, Marx proves the labor theory of value. His critical investigations return the market from the abstract and naturalized sphere of ideology to the scientific sphere of concrete reality.

Who is this Hegel Marx writes of? Before getting to that, I need to address a philosophical debate that lies in back of Marx’s reference, a very old argument between what we know today as idealism and materialism. The dispute achieved it modern form during the Enlightenment, most clearly in German idealism from the mid-18th century and the critique of idealism by the materialists in Germany and England in the 19th century. Idealism is the position that experience and reality are explicable in terms of the mind or spirit, that is, in non-materialistic things. Idealists see ideas as the most important things. Ideas determine reality. Against this view is the materialist view, which holds that an exterior world shapes ideas and this world is objectively knowable through science. One variant of this view is that all that really exists is matter, or physical things, and that these things, these substances, are what we mean when we talk about “material.” The world around us is not the result of the mind or consciousness, but rather phenomena of the mind and consciousness are the products of physical processes. This is a narrow reductionist conception of materialism. In contrast, historical materialism, the approach Marx develops, is a materialist approach that captures the objective mind-independent aspects of social reality, but preserves agency, and with it the conscious act of changing the world. Historical materialism is thus simultaneously theoretical and practical. Marx maintains that we can study social structure as a material thing, much like gravity, even though we cannot directly perceive it, as we know it in terms of its effects and, moreover, transform it through action.

The idealism that inspired Marx is Hegelian idealism. Hegel developed a particular dialectical method that can be characterized as movement of the reality from the abstract (or immediate), through the negative or mediated, arriving at the concrete. A full exploration of the dialectic would take us well beyond our purposes here, so a brief summary of the idea will have to suffice. For Hegel, any idea must pass through a negative phase (negation or mediation) before becoming concrete and historical. An idea confronts another idea or reality—or in practice becomes a reality—which is always different from the original idea. The idea is thus transformed, become more highly developed, as the mind comes to know more fully the reality of its action. Hegel refers to this process as “becoming.” The process of becoming preserves the useful elements of an idea, object, or system, while transcending its limitations through successive approximations, which in turn alter the idea. Hegel applies this idea to argument and history. So does Marx.

An example from Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit should suffice to illustrate the dynamic. God, which in Hegel’s philosophical terms is the “Absolute,” objectifies its self in nature. Nature is the alienated self-expression of Spirit, a necessary moment in the struggle of the divine spirit. God reflects on its nature to achieve a deeper consciousness of its self. In concrete terms, Jesus, the word made flesh, was such a moment. God—the Absolute—manifests the idea of itself in physical human form and thus comes to know itself—along with all of the world who would hear the good news—at a deeper level. More broadly, history is the way God comes to know itself, and God must ultimately struggle with this work; humans make the history and culture that makes it possible to know God. What Hegel is describing is a process that, in its development, through the abstraction and its negation (or sublation), synthesizes a higher unity. Beings know themselves through each other and come to know the greater reality they create together. For Hegel, the mind, whether it is the individual human mind of the absolute mind (God) must pass through a struggle for freedom before realizing itself.

Hegel’s conception of freedom, which differs markedly from the liberal view, depends on the understanding of the context of thought and action. For liberals, freedom is defined in negative terms. Liberty is an empty vessel into which each individual places her interests, or, more accurately, her preferences. Freedom is defined in terms of what it’s not: the absence of coercion. For Hegel, freedom is not judged by degree of separation or alienation from society, i.e. others, but the degree of participation in society—in collective efforts to shape history in pursuit of higher levels of consciousness and understanding. Freedom is not unhampered individual activity, as liberals suppose; rather freedom results from rational control of human activity in social contexts, in the making of history collectively, as a people. Freedom is present when people are able to exert meaningful control over their lives as political actors.

Judged from the Hegelian standpoint, the standard liberal conception of freedom is exposed as superficial, for it does not ask why individuals make the choices they make.

Judged from the Hegelian standpoint, the standard liberal conception of freedom is exposed as superficial, for it does not ask why individuals make the choices they make. Hegel argues that external and internalized forces condition choices. The individual is a product of history and culture, and in this process the individual comes to develop her preferences for things and states. But the individual also has interests that lie outside of her own consciousness, which she may discover through a dialectical process. But it is not automatic. It requires education. This idea of freedom becomes central to Marx’s radical conception of freedom.

One of Hegel’s students, Ludwig Feuerbach, after first being faithful to his master’s system, began to see problems in his argument—indeed in idealism generally. He came to reject idealism in favor of materialism. He found in Hegel’s system that everything in history and nature is interpreted from the standpoint of development conceived of in such a way that the last stage is regarded as the final moment of a totality that includes all the previous stages. Thus the end of history, with a perfect society, is causing history to unfold itself towards that end. If this strikes you as having a religious character, you are right. Thus, Feuerbach accused his mentor of forming an illegitimate teleology: the results of history and nature call into existence the causes of those results. In other words, Hegel’s history is reverse engineered. Hegel would remind Feuerbach that there is a designed: god or, in Hegel’s terms, the Absolute. But Feuerbach wondered, “Why does the absolute need to struggle know itself when the final moment is already present from the beginning?”

Feuerbach is suspicious that Hegel’s system misrepresents nature, culture, and religion, because it ignores historical variety and cultural particularities. Christianity is assumed to be the Absolute religion. What of other religions? On what basis can Hegel be certain that the god of the Judeo-Christian religion is the one and only god? After all, different gods and religious systems exist in history and across cultures. Once history and culture entered the problem in this way, Feuerbach begins to perceive that Hegel has stood the order of things on its head. Hegel has put ideas before the material world, when, in fact, it was the other way around: ideas come from history, and history is the product of material social relations.

As Shlomo Avineri writes in The Social and Political Thought of Karl Marx, “Hegel’s process of overcoming these dichotomies had begun at the wrong end.” Hegel’s philosophy “could not disentangle itself from its internal contradictions,” therefore “it was bound to end as a mystification.” So to correct the problem one has to set Hegel on his feet, as Marx cleverly put it. Feuerbach called this procedure the “transformative method.” He took speculative philosophy and flipped the predicate and subject. “Thus man would be liberated from the alienated power his own mental creations had over him.”

This led Feuerbach to write one of the most notorious books in history, The Essence of Christianity. Feuerbach argues that all religion appears as mythology to a given society except the particular religion that prevails in that society. Religion is a social/historical construction that reflects the idealized features of the society in which it appears. Thus “god” is only the projections of the consciousness of the species in a given time and place. It is not a real transcendent thing. In fact, belief in the supernatural alienates the individual from his true relations with society and nature, as well as the origins of her creative energies: himself. “In the consciousness of the infinite, the conscious subject has for his object the infinity of his own nature.”

The Essence of Christianity was reviled at the time for its atheism. And Marx saw in it the solution to the problem of philosophy. It still preserved Hegel’s method, but made it scientific. Marx summarizes in his 1844 A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: “For Germany, the criticism of religion has been essentially completed, and the criticism of religion is the prerequisite of all criticism…. The foundation of irreligious criticism is: Man makes religion, religion does not make man.” Marx reminds the reader: “man is no abstract being squatting outside the world. Man is the world of man – state, society. This state and this society produce religion, which is an inverted consciousness of the world, because they are an inverted world.” He continues:

It is, therefore, the task of history, once the other-world of truth has vanished, to establish the truth of this world. It is the immediate task of philosophy, which is in the service of history, to unmask self-estrangement in its unholy formsonce the holy form of human self-estrangement has been unmasked. Thus, the criticism of Heaven turns into the criticism of Earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law, and the criticism of theologyinto the criticism of politics.

But Feuerbach does not solve the other problem Marx wants to get a handle on, the false notion that knowledge and action should or even can be divided between “is” and “ought.” Like everything else, Hegel attacks it from the standpoint of idealism. Marx believes that solution to the problem lies within reality itself, where the source of all ideas are ultimately to be found. To quote Avineri again: “For Marx, Hegel’s chief attraction lay in his philosophy’s apparent ability to become the key to the realization of idealism in reality, thus eliminating the dichotomy Kant bequeathed to the German philosophical tradition.” Avineri continues, “Coupled with this Marx developed an immanent critique of the Hegelian system.” Marx saw in Hegel’s philosophy a method “to bridge the gap between the rational and the action.” Much like the mystification of Smith’s invisible hand, Hegel’s theory of social and political institutions hid the answer because it removed it to abstract thought, rather than finding it in the material forces of history.

Turning to Feuerbach, Marx writes:

“Feuerbach starts off from the fact of religious self-estrangement, of the duplication of the world into a religious, imaginary world, and a secular one. His work consists in resolving the religious world into its secular basis. He overlooks the fact that after completing this work, the chief thing still remains to be done. For the fact that the secular basis lifts off from itself and establishes itself in the clouds as an independent realm can only be explained by the inner strife and intrinsic contradictoriness of this secular basis. The latter must itself be understood in its contradiction and then, by the removal of the contradiction, revolutionized.”

These observations led to Marx’s famous dictum: “Philosophers have only theorized the world, the point is to change it.”

For Marx, “human being” is social product realized through society and the labor process. Humans objectify society through collective activity, realizing their essence through social action. But in class-divided societies human beings are alienated from their essential activities the objects they bring into existence from self and others. The central problem in history is this: the majority has lost control over the act of creating the world—and the world they created. Only when alienation is overthrown will humanity be free. The solution: Marx advocates substantive freedom, which means democratic control over society’s productive forces and the direction of history lays the basis for human freedom. Freedom is closely linked not to popular and representative political democracy, but to economic democracy or socialism. For this reason, Marx is the figure most closely associated with positive freedom.

The central problem in history is this: the majority has lost control over the act of creating the world—and the world they created. Only when alienation is overthrown will humanity be free.

Thus the struggle for democracy requires a scientific method. And in the year Darwin gave to the world the scientific basis of natural history, Marx delivered to that same world the scientific basis for human history; A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Marx writes in the Preface:

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations [that] are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production.

The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness.”

We can depict Marx’s model with this diagram:

Human labor, in the center of the diagram, is the foundation of production. People create the world and their selves through the power of labor. Without action, nothing happens, nothing is possible. And humans have no choice but to act. In the “Preface” to the first edition of The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884), Engels identifies the two imperatives of the species:

According to the materialistic conception, the determining factor in history is, in the final instance, the production and reproduction of the immediate essentials of life. This, again, is of a twofold character. On the one side, the production of the means of existence, of articles of food and clothing, dwellings, and of the tools necessary for that production; on the other side, the production of human beings themselves, the propagation of the species. The social organization under which the people of a particular historical epoch and a particular country live is determined by both kinds of production: by the stage of development of labor on the one hand and of the family on the other.

Marx writes that the fundamental elements of the labor process are the work itself, the object on which work is performed, and the instruments produced by and use in that work. Objects of labor can be objects found in nature or objects already worked up in the labor process. All objects must be appropriated from nature by human labor. Some of these objects become instruments of labor, which is a thing that focuses the worker’s activity on an object, such a tool or a machine or a road or a building. These two elements comprise the means of production. The means of production are simultaneously the product of human labor and a means through which human labor produces. Taken all together, these comprise the forces of production. The forces of production embed in social relations that are sustained by these forces. These are defined primarily as property relations, most importantly the relations of social class, although caste (race/ethnic and gender) relations are also relevant. The forces of production and the social relations taken together are conceptualized as the mode of production, or civil society, to use Hegel’s terminology. This is the base of society (the substructure is nature).

Upon this base rises the superstructure, or political society comprised of (1) the state and law, that defends the prevailing property relations by force, (2) the ideology or set of ideologies, including religion, racism, sexism, and other repressive ideas that animate coercive structures, that legitimizes the prevailing property relations with notions of right and wrong, good and bad, insiders and outsiders, and finally (3) consciousness, collective and individuals. Ideas function to justify the status quo and are rooted in material control of the forces of production. Marx and Engels in the German Ideology, penned in 1845, put it this way:

The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class that is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class that has the means of material production at its disposal has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it. The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships, the dominant material relationships grasped as ideas; hence of the relationships which make the one class the ruling one, therefore, the ideas of its dominance.

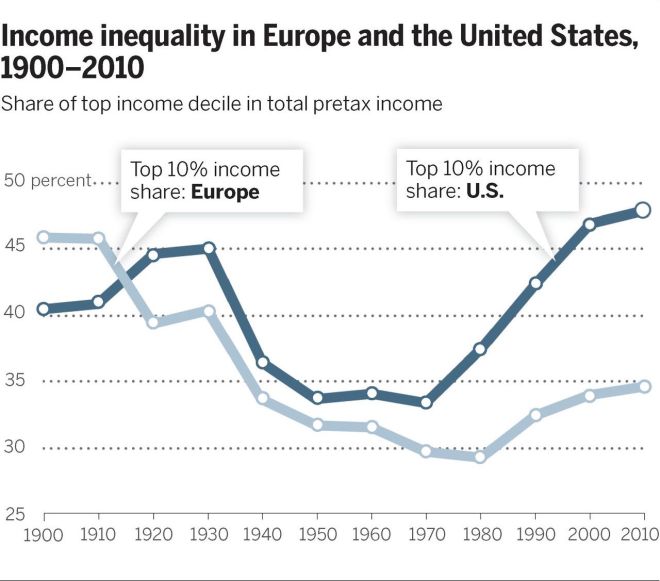

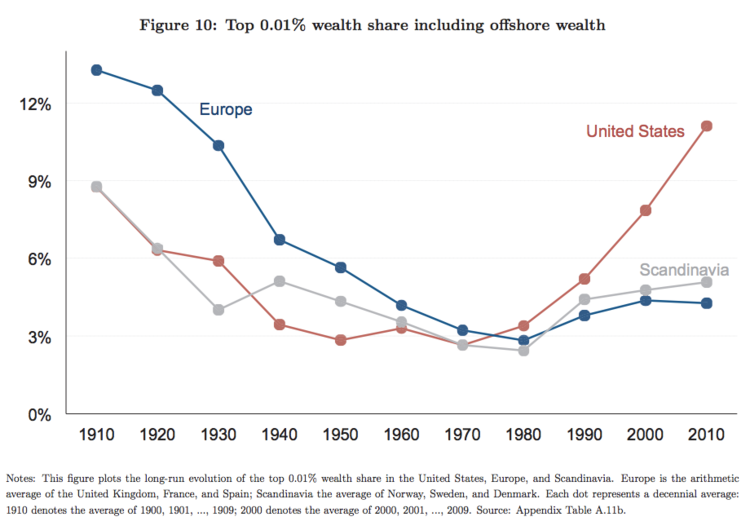

History moves through a dialectic process: primitive communism (which includes gather-and-hunter societies, as well as horticultural), which comprises most of our roughly 400,000-year existence as a species, Asiatic (large-scale agricultural), ancient (tributary), feudal, and capitalist. Each of these stages is a mode of production determinable by an analysis of its social relations. Under primitive communism there is neither class system nor state and law. State and law come into existence with the emergence of social class. Before social class came into existence, the fruits of labor – that is, the social product, including the social surplus, or excess production beyond subsistence – were shared among all in the community. With the emergence of large-scale agricultural, and the production of substantial social surplus, it became possible for some to live without working. These families became the rulers. They developed religion and other ideologies as a means of controlling the population. Each successive stage has led to great inequality between those who produce the social surplus and those who appropriate it without working. Capitalism represents the highest stage of exploitative relations. Here’s what that looks like:

What explains the transformation from one stage to another? Marx writes,

In studying such transformations it is always necessary to distinguish between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, artistic or philosophic—in short, ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out. Just as one does not judge an individual by what he thinks about himself, so one cannot judge such a period of transformation by its consciousness, but, on the contrary, this consciousness must be explained from the contradictions of material life, from the conflict existing between the social forces of production and the relations of production.

The static model presented above is abstracted from history; for history shows that the status quo gives way to transformational or revolutionary moments—that, alas, do not always give way to revolutions—driven by the internal contradictions to the system, such the periods of realization crisis or crises of overproduction, such as we have been experiencing in our own time:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or — this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms — with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure.

This is what Marx and Engels are describing in the Communist Manifesto having happened with feudalism giving way to capitalism. Now it is our turn to usher in the next great epochal change, from capitalism to socialism.