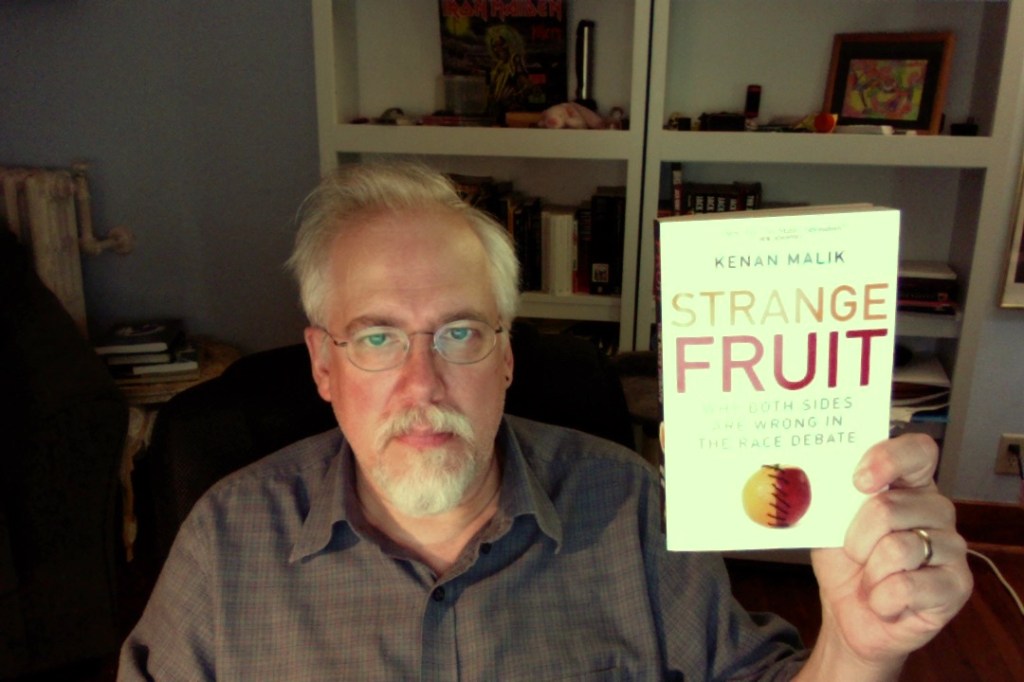

Kenan Malik, in the foreword to his 2008 book Strange Fruit: Why Both Sides are Wrong in the Race Debate, writes “that, for all the vitriol directed at [James] Watson [the co-discoverer of DNA’s double helix structure punished for suggesting in an interview with the Sunday Times that blacks were cognitively inferior], racial talk today is as likely to come out of the mouths of liberal antiracists as of reactionary racial scientists.” “The affirmation of difference, which once was at the heart of racial science,” he continues, “has become a key plank of the antiracist outlook.” (For a lengthy discussion of Malik’s work see my “Kenan Malik: Assimilation, Multiculturalism, and Immigration.”)

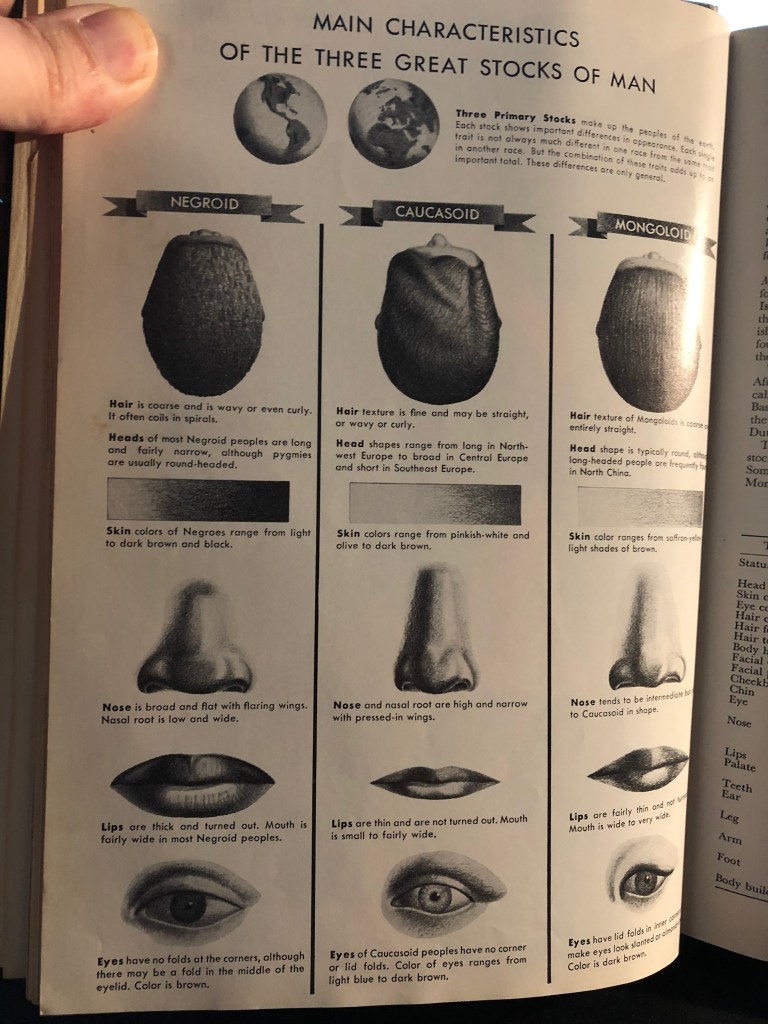

In the battle against racism in the twentieth century, liberals either denied racial differences altogether or at least rejected the doctrine of racial hierarchy. Humans are, they argued, all the same beneath the skin, their outer appearance no indication of patterns of behavioral tendencies, cognitive ability, or cultural and societal potential. It followed that organizing society along racial lines enjoyed no rational justification. More than this, it was wrong and harmful. But in the post-civil rights era there emerged on the left a movement that sought to commandeer the language of racial difference and use it as a cudgel with which to attack the liberal and secular values of Western society. “The paradoxical result,” Malik writes, “has been to transform racial thinking into a liberal dogma. Out of the withered seeds of racial science have flower the politics of identity. Strange fruit, indeed.”

How did this happen? “Where radicals once championed scientific rationalism and Enlightenment universalism, now they are more likely to decry both as part of a ‘Eurocentric’ project,” a move facilitated by the corruption of philosophy and science by postmodern ideas that had found purchase in the academy. “Over the past three decades,” Malik, writes, “postmodern theory has made the link between the physical subjugation of the Third World through colonialism and the intellectual subordination of non-Western ideas, history and values.” This has led to the development of “cultural racism” As French philosopher Étienne Balibar announces in his essay “Racists and Anti-racists,” “we have passed from biological racism to cultural racism.” (See the last section of my essay “Smearing Amy Wax and the Fallacy of Cultural Racism” for a detailed analysis.)

“All knowledge systems, including those of modern science,” writes philosopher Sandra Harding, one of the most influential postmodern thinkers of our time, “are local ones.” The dominance of Western science across the planet is “not because of the greater purported rationality of Westerns or the purported commitment of their sciences to the pursuit of disinterested truth,” she contends, but “because of the military, economic and political power of European cultures.” (One might ask how the West came by this power.) Harding casts science as “politics by other means.” For thinkers of her ilk, the content of Western civilization—liberalism, rationalism, secularism—is an imposition on the rest of the world; its ideas have not won because they are better but because those who espouse them—white Christian men—are imperialist.

The postmodern epistemology expounded by scholars such as Balibar and Harding have produced regressive effects on developing countries and various communities in developed ones. As historian Meera Nanda observes: “postmodernism in modernizing societies like India serves to kill the promise of modernity even before it has struck roots.” The influence of postmodern ideas “has totally discredited the necessity of, and even the possibility of, questioning the inherited metaphysical systems, which for centuries have shackled human imagination and social freedoms in those parts of the world that has not yet had their modern-day enlightenments.” (Perhaps an irony in all this is that postmodernism, like modernism, is a Western idea.)

Antiracism is pitched as the policy or practice of opposing racism and promoting racial tolerance. That’s the standard dictionary definition, anyway. However, in conception and practice, this is not how antiracism operates. Antiracism is a manifestation of racial thinking and is not only inadequate for combating racism but is one a major form racism takes today—racism defined as a system that essentializes cultural differences in human populations in racial terms. I no longer describe myself as an antiracist because I reject the racial thinking that inheres in the practice. It is wrong to say that every member of race of people possesses something for what should be two obvious reasons: (1) there is no such thing as race and (2) because collective and intergenerational guilt are theological constructs. The contemporary practice of antiracism is therefore irrational. This blog entry explains that position.

* * *

Antiracism finds its origin in the progressive political-ideological strategy of combating racism by replacing the concept of race with the concept of culture in explaining human behavioral and cognitive variation and establishing cultural relativism as a political and scientific worldview.

The first part of this is welcome. The claim that race explains differences in human populations is the essence of racism. The scientific consensus is that race is not a meaningful biological construct. What the evidence shows is that differences in human populations (and this includes the distribution of phenotypic features used to identify racial types) is the product of migration, cultural forces, and social organization. Moreover, cultural relativism is a sound methodological stance for studying cultural differences and similarities. The careful researcher should make efforts to ensure his own cultural standpoint does not interfere with practice rooted in objective epistemology (I reject the postmodern claim that there can be no such thing).

However, cultural relativism makes for awful for moral and political standpoint, as it rationalizes actions and attitudes that are exploitative, false, oppressive, and unhealthy as appropriate to the culture under consideration. This error is, to some extent, the consequence of functionalist thinking in anthropology. But it also expresses postcolonialist desire and anti-West loathing, the character of which is postmodernist (and post-Marxist). In effect, cultural relativism obviates individualism and human rights. All those things that define modernity—democracy and universal suffrage, diversity of opinion, freedom to produce and access knowledge, gender equality, individual liberty, sexual emancipation—are treated as a particular point of view, a perspective that hails from an imperialist civilization. There is nothing in these things enjoying universal appeal, the argument goes.

The ethic of cultural relativism stands in place of what one might on the face of it consider an authentic antiracist standpoint, namely an anti-ideological practice opposing the tradition of racializing populations, by which is meant the system of beliefs positing that Homo sapiens is meaningfully organized as biological types called “races.” In conception and in practice, what is called “antiracism” is the policy or practice of opposing criticism of non-European cultures and promoting tolerance and even acceptance of nonwestern norms and values. But race and culture are different things, with the former conceived as a constellation of traits obtained via biological heredity, the latter describing an observable system of assumptions, beliefs, norms, and values learned via socialization that inhere in an institution or a society. By confusing the concepts, antiracism confuses its audience. It becomes ideological.

If the premise of racism is accepted, then individuals are born as members of a given race. In this way, race is caste; one is eternally tagged by what Erving Goffman called “tribal stigma.” For racists, the reality of race explains cultural variation. For many of those who reject racism, even if they recognize race as a social construct (which clearly it is), they understand that no person is born with culture or a religion. Culture is acquired after one is born. An American whose great-grandparents immigrated from Japan and whose ancestors only married others of Japanese ancestry, would carry around with him American culture. He would not, unless he were a Nipponophile (and even then, whether his sensibilities could be said to reflect the emic is doubtful), carry around Japanese culture. Japanese culture is not encoded on one’s genes. At the very least, if humans are born with some innate cultural sensibilities, as the evolutionary psychologist might suppose, those sensibilities are not racially differentiated. There’s no evidence for this.

Race and culture are plainly different because, granting for the sake of argument an objective reality of biological race, or at least admitting to the common-sense recognition of racial types, a culture may be—and cultures often are—multiracial in character. However, things tend to end badly for those civilization without a unifying culture. Historian Victor Davis Hanson writes, “Ancient Greece’s numerous enemies eventually overran the 1,500 city-states because the Greeks were never able to sublimate their parochial, tribal, and ethnic differences to unify under a common Hellenism.” He cites numerous other examples. His point is not that multiracialism presents a problem for stable and prosperous societies, but rather that multiculturalism does. At the heart of multiculturalism lurks a repudiation of the necessity of a common culture for unifying a people around a common social purpose. In contrast to ancient Greece, Rome “managed to weld together millions of quite different Mediterranean, European, and African tribes and peoples through the shared ideas of Roman citizenship (civis Romanus sum) and equality under the law. That reality endured for some 500 years.”

Of course, what has always been true is that culture is produced everywhere by individuals of the same species. A society can only be described as multiracial when races are presupposed. One would think that the idea that cultural differences are racial differences, that races are entitled to separate cultural systems because of phenotypic affinity, is what antiracism was devised to counter. Instead, assuming notions advanced by Horace Kallen in the early twentieth century, antiracism promotes the Balkanization of society—that is a society splintered into hostile and uncooperative groups along lines of ethnicity and religion, to use a common definition—and recast the notion that an overarching nationalist consciousness as racist.

Étienne Balibar is a useful example of a proponent of the view that nationalist consciousness is racist. Why is it racist? Because, he argues, it is exclusionary. He denies that one can speak of an absolute universalism; universalism is always inscribed in a civilization, of which there are plainly several. He claims that “modern racism is [the] dark face of the republican nation, and one which incessantly returns, thanks to the conflicts over globalization.” He cites France and the principle of laïcité, or state secularism, noting that, in France, a “nation increasingly uncertain as to what its values and its objectives are, laïcité less and less appears as a guarantee of freedom and equality between citizens, and has instead set to work as an exclusionary discourse.”

But this misses the point of the work of civic nationalism. It is not exclusionary of individuals but of norms and values that undermine modernity, that deny the universalism of human rights. “A diverse America requires constant reminders of e pluribus unum and the need for assimilation and integration,” writes Hanson. “The idea of Americanism is an undeniably brutal bargain in which we all give up primary allegiance to our tribes in order to become fellow Americans redefined by shared ideas rather than mere appearance.”

This is what antiracism rejects, namely the emancipation of the individuals from the imposition of racial, ethnic, and religious identities. Instead, the antiracist, in defining the Muslim as a race, expects she will wear the hijab as a skin color in order to mark racial difference (see Muslims are Not a Race). It only seems confusing to read Balibar defining universalism in its basic form as “a value that designates the possibility of being equal without necessarily being the same, and thus of being citizens without having to be culturally identical” until one understands that race and culture are conflated in his thinking. At the same time, he claims the following: “The universal does not bring people together, it divides them. Violence is a constant possibility.” Not only Balibar want to find universalism in multiculturalism, he blames violence on opposition to such a formulation. (Read Verso’s full interview with Balibar here.)

Modern-day accusations of racism leveled by antiracists therefore include in their scope not only those persons who believe they are biologically or genetically superior to others or they are some way essentially or intrinsically racially better than members of other races (one cannot rule out idealist claims of racial difference), but also cover those who believe that certain ways of life are superior or better than other ways of life. This is why Balibar wonders, “How could [Immanuel] Kant be both the theorist of unconditional respect for the human person, and the theorist of cultural inequality among races?” “This,” he claims, “is where the deepest contradiction—the enigma, even—lies.” When one criticizes Islam, and therefore Muslims, since Muslims are those culture-bearers bringing Islam, one risks being accused of racism. But what does religion have to do with race? How does it contradict unconditional respect for the human person to note cultural inequality? What is race stuck in there? I am not here defending Kant, but noting the problem of the point on its face. Balibar assumes at every step of his case that race and culture are intrinsically linked.

In his Racism Without Racists: Color-blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America, first published in 2003, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva identifies what he refers to as “central frames of color-blind racism.” Two of these frames bear directly on the present discussion.

The first is the frame of “abstract liberalism,” involving ideas associated with political and economic liberalism, that is the values of equal treatment under the law and personal or individual liberty. Bonilla-Silva cites as an example of the “new racism” the objection to preferential treatment as a violation of the principle of opportunity. He argues that opposition to preferential treatment ignores the fact that people of color are severely underrepresented in good jobs, schools, and universities. Rather than explain the causes of minority underrepresentation, which may or may not have something to do with racism, Bonilla-Silva assumes racial inequality is the consequence of racism, and, to remedy this situation, people of color should be given preference in admission and hiring, and those who object to positive discrimination are racists even if they no make racists arguments. I expect that the reader will see that Bonilla-Silva has made no argument here. He has merely told us that he wants to call people who are critical of preferential treatment “racists” because he supports preferential treatment. He tells us why at the end of the interview below.

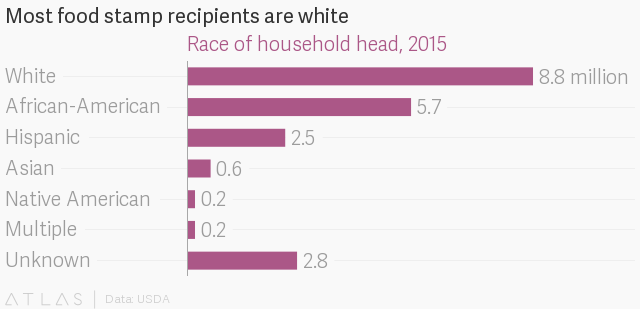

The second frame is “cultural racism,” which “relies on culturally based arguments such as ‘Mexicans do not put much emphasis on education’ or ‘blacks have too many babies’ to explain the standing of minorities in society.” One might therefore think that these stereotypes are not examples of racism. Bonilla-Silva concedes that only white supremacists root such prejudices in biology. However, according to Bonilla-Silva, “biological views have been replaced by cultural ones.” To illustrate, he quotes a male subject named George interviewed in Katherine Newman’s Declining Fortunes (1994). George says that he believes in morality, ethics, hard work—“all the old values.” What George doesn’t believe in are handouts. He criticizes the welfare system for creating dependency on the government. Newman observes that “George does not see himself as racist. Publicly he would subscribe to the principle everyone in society deserves a fair shake,” an observation which Bonilla-Silva uses to punctuate the title of his book: “Color-blind racism is racism without racists!” But, since culture is not race, why would criticizing welfare be racist? Neither Newman nor Bonilla-Silva present evidence that George is racist. Rather they are making criticism of welfare an act of racism. But most welfare recipients are white.

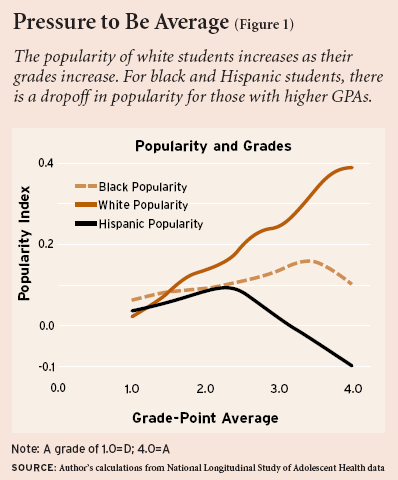

Bonilla-Silva says in the interview I shared above that, as a social scientist, his role is not to “provide the path to the promised land.” At the same time, as a person of color, he “has a stake in improving our position.” Yet there are people of color, for example Glenn Loury of the Watson Institute at Brown University, who cites research that shows that black and Hispanic youth who aspire to scholastic excellence are accused by their peers of “acting white” and that this social pressure reinforces a culture of underachievement, reproducing the conditions with which blacks are more likely to be associated. Anthropologists Signithia Fordham and John Ogbu identified this phenomenon in the Urban Journal in 1986. They documented an “oppositional culture” in which black youth dismissed academically oriented behavior as “white.” In the late 1990s, Harvard economist, Ron Ferguson, found a similar anti-intellectual culture in another setting. Columbia’s John McWhorter contrasts African American youth culture with that of immigrants (including blacks from the Caribbean and Africa), and notes that the latter “haven’t sabotaged themselves through victimology.” These are all persons of color. From Bonilla-Silva’s standpoint, what do they have a stake in?

Harvard’s Ronald Fryer, in his 2006 article “Acting White,” while finding fault with the previous explanations nevertheless concludes that “the prevalence of acting white in schools with racially mixed student bodies suggests that social pressures could go a long way toward explaining the large racial and ethnic gaps in SAT scores, the underperformance of minorities in suburban schools, and the lack of adequate representation of blacks and Hispanics in elite colleges and universities.” He argues that there is a need for new identities in communities of color. “As long as distressed communities provide minorities with their identities, the social costs of breaking free will remain high” he writes. “To increase the likelihood that more can do so, society must find ways for these high achievers to thrive in settings where adverse social pressures are less intense. The integrated school, by itself, apparently cannot achieve that end.”

These claims are racist in Bonilla-Silva’s formula (or are they only racist when white scholars make them?). The problem is not merely that Bonilla-Silva is wrong. His arguments perpetuates the situation of inequality. If policymakers don’t recognize the problem and address it properly for fear of being smeared as racist, then society fates a proportion of minority youth to habits that, at least in part, perpetuate racial inequality in America—which Bonilla-Silva is right to complain about. Wouldn’t failure to honestly confront a problem in communities of color be a better example of racism than the one Bonilla-Silva puts forward?

There is no objective truth to claims that race has a biological reality. These claims result from ideology. Ideologies are cultural products. All ideologies, indeed all cultural products, are subject to vigorous interrogation—if humanist principle is observed. In a society where cultural criticism is permitted, thinkers will criticize those aspects of Western culture that produced and reproduce modes of racial thinking, as well as modes of sexist and heterosexist thinking. Or they will interrogate subcultures that systematically disadvantage minorities, independent of what the majority thinks or does. Thinkers should also be able to criticize those aspects of Islamic culture that, for instance, produce and continue to reproduce patriarchal attitudes. And so on. (See Racisms: Terminological Inflation for Ideological Ends.)

If one is convinced that the criticism of nonwestern culture or minority subcultures is racist, then those feminists who endeavor to root out patriarchal attitudes wherever they’re detected risk being labeled as racist and marginalized. This marginalization comes at cost for women and girls who live under the structure of patriarchy in the Islam world, a structure that denies them equal rights, personal freedom, and other rights and liberties associated with modernity. The same is true for black youth when criticisms of “acting white” are suppressed by accusations of racism. These are not exercises in exclusion, but the work of emancipation.

Since culture cannot be a result of race (rather racism is the result of culture), it makes no sense to describe cultural criticism as racist when there is not racism moving it. To be sure, there are people who criticize culture with the assumption that racial difference explains it. But, as we have established, those people are racists. That is what the term racism meant to capture. Absent that it is just cultural criticism. Bonilla-Silva’s argument is vacuous even if consequential.

If by “white” we mean something other than race, then criticizing white culture—or celebrating white culture, for that matter—would not be racist. But why would anyone describe the culture of the West as “white” if there is no such thing as a white race? Racism is the belief that the human population is meaningfully organized into racial groups and, moreover, that these groupings explain behavioral tendencies, cognitive ability, cultural accomplishment, and moral aptitude. If criticism of culture does not contain this belief it is by definition something other than racism. The idea of “white” and “black” cultures, if it is to mean anything racial, assumes as reality what science has proven false.

* * *

Antiracism in practice tacitly accepts a core premise of racism: it associates culture with a race and places these in an explanatory framework. It claims that western culture is the culture of white people and that, for this reason, there is something wrong with it.

Antiracists could say that racism as an element in a culture is a bad practice and should be eliminated without condemning the culture in which it is found. Racism is, after all, an aberration in a culture committed to the value of individualism. The more Westerners realize the ideals of the Enlightenment, the more peripheral the irrationalisms of race (and religion) become. One could declare an entire culture is racist or in some way harmful to people. But the antiracist wishes to say a great deal more than this. He wishes to say that all white people are racist because they are white and that the culture they produce is inherently racist for this reason. (What would be the solution to this problem if true?) Rightwing racism has a version of this logic: all white people belong to a tribe (whether they know it or not) and white culture is the product of the white race and it’s good for this reason.

This is the consequence of essentializing culture and religion in identitarian movements left and right: both standpoints root in racial thinking. The difference one would as least hope for is that, for the left, racial thinking would be seen as a bad thing. It used to be. But for today’s left, race identitarianism enthusiastically commits the crime it condemns: it hypostatizes race and places it at the center of its politics.

Consider the rhetoric of race privilege. When antiracists accuse people of possessing “white privilege,” the standard formula holding that “all white people” are privileged in some way that disadvantages members of nonwhite races, they are essentializing race. The assumption is that there is such a thing as the white race, and that intrinsic to it is race privilege. We know race privilege is intrinsic to the white race because every white person possesses it. It comes with their skin color. It is a feature of having been born white. If I, as a white person, deny being privileged in this way, then I am guilty of denying something I possess by virtue of my race. I am doubling down on my racism. I cannot get better if I do not admit that I am sick.

It’s all very circular and very racist. I am criticized and often condemned for my skin color. For many, hatred towards me on the grounds of my whiteness is at least understandable. But it’s not. It irrational. It’s exactly like supposing a black man is inferior to those who are not black because he is black. We have no evidence for this claim beyond racial identity. Privilege is assumed to be an actual and universal thing without requiring any evidence presented beyond the mere fact that I am “white,” which proves I am privileged. It’s as if there is still a rule in effect that directs blacks through a side door and up the stairs to the balcony of the movie theater so that whites do not have to mingle with them. But the United States abolished privileges on the basis of race in the 1960s. We’re taught to overlook the significance of the fact that, today, it is illegal—or should be illegal, anyway—to discriminate against persons on the basis of their perceived race.

But this last part is not exactly correct. Race is still considered in admissions to educational institutions, as well as in hiring in the public sector and at many business firms. You may not find many people who still believe in the old racism, but you will find plenty of persons who believe in this new idea of racism that makes it appropriate to decide matters based on racial classifications that work in a “progressive” direction. Members of the “white race” are, like members of the “black race,” human beings, each proven members of the same species. Yet race must necessarily be imagined as real in order to make the claim that one is privileged (or otherwise) by virtue of it.

The natural scientist tells us that race is not a thing (unless he is a racist). The social scientist says, “Not so fast.” Today, he accepts demands for racially segregated spaces, programs, and benefits, as if the United States did not more than half a century ago declare that the doctrine “separate but equal” is anything but equal. Progressives talk about the need of some people—white people—to pay reparations for a crime they did not commit (see my essay “For the Good of Your Soul”). These demands require coding people on the basis of selected and superficial phenotypic characteristics in order to discriminate against them on that basis. One may decry, “Isn’t this racism?” But one will be told that it is in fact racist to say, depending on the race in question, that recognition of racial types and differential treatment on the basis of race is racism. That’s the straitjacket into which Bonilla-Silva wishes to put critics of discrimination.

The antiracist sends conflicting messages. He promotes racial consciousness, and then insist that only some races have a right to organize their politics around it. He tells people they suffer from implicit race bias because they recognize race, but then criticizes them if they behave as if they don’t see race. He tells people to treat people as individuals but then accuses them of racism if they say they don’t see race. The critical race theorist, such as Bonilla-Silva, calls this “colorblind racism.” The antiracist claims that racism is an invisible structure that works its evil subtly and only by recognizing race and making decisions on that basis, with a certain selective logic, can we counter its effects.

In an act of extraordinary reification, the antiracist treats individuals as concrete representations of abstract groups, which are defined into empirical existence with statistical measures, aggregated data selectively touted when beneficial while rejected when not according to whom it benefits. Data showing that whites-as-a-group are better off than blacks-as-a-group is proof of the justification for positive discrimination. Data showing blacks-as-a-group commit more violent crime than whites-as-a-group cannot be accepted as grounds for policy formation because only individuals should be judged for their actions. (See Demographics and People.) Are we supposed to treat people as individuals or as racial types? It depends on abstract notions of power and direction in the cosmology of intergenerational guilt. And, of course, racial typing is also desired when organizations need to act as if persons with particular constellations of phenotypic features can stand in for abstract racial or ethnic group and thus should be admitted, displayed, or hired for this reason.

Antiracism does the work of racism. It determines worth based on race and other abstractions. It is rightwing racism’s leftwing mirror image, which is why we’re taught at a young age that there is no such thing as “reverse racism.” Which is in a way true. There is only racism.

This is how religion works. You are not supposed to examine its assumptions or true aims. Faith is a reflex. Angels, demons, heaven, hell, sin, salvation—these things are assumed as given. Naturally you will want to organize society around them if they are real. When you actually examine them, religion falls apart. They are not real things, but myths designed to control you. It is an absurd exercise to debate the reality of different sorts of demons when there is no such thing as one. Yet this is what happens. A rational person asks himself, why am I believing in unreal things? But people believe that race is real, so you have to operate on that basis, we are told. You may not see it, but others do. Should I suffer anything on account that people still believe in sin? How is that a remotely reasonable demand? One hundred years ago people believed that race was real. Some people believed it was a repugnant way to organize society, but they grew up in a culture that told them it was real. But then they examined the construct and found that it is not an actual thing. It only persists because people insist on keeping it alive. Why should that be my problem?

The ideas that we accept fictions or organize our lives around untruths because some people still believe them makes no rational sense. Why are those of us who have moved on pulled into such orbits? I’m an atheist. It’s not my religion. I’m not a congregant in the church of racial identity. Why should I be taxed for this or expected to seek salvation from the sin its moral entrepreneurs say I possess by virtue of my existence? There should be in a free society no gravitational force in such abstractions.

This much the postmodernist gets right: it is because of power that individuals are compelled to submit to the tyranny of fictions. Even though we now know race is not real, those who control our institutions, who organize our society—who make our law and form our politics—force us to submit to the fiction of race. We could move on from it. But those who demand we keep the damn thing going put their power where their desire is. We are compelled to participate in a delusion because there are real punishments for refusing to do so. It’s like challenging a witchfynder during an Inquisition. That makes you a witch.

My father is not an American Christian because of his race. He is an American Christian because he was born in a particular country in a particular culture. That is what makes him white, too. Had he been born somewhere else or in a different we would be describing him differently. He would be committed to different things. But whatever time and place he may exist in, he will always be Homo sapiens. That is the enduring truth. That is what makes humanism universal. Racism is wrong because it considers individuals on the basis of an abstract condition they were born into; it treats a cultural category as a natural one. There are no good or bad races apart from racist ideology. But cultures and religions are objectively not good for people. Some cultures and religions cut off body parts, subordinate women and girls, and persecute homosexuals.

If you are a postmodern type and chalk up these sorts of things to cultural and moral relativism, then this talk of human freedom and rights is lost on you. But if you recognize that each person is a member of a single species that comes with needs like every other animal species, then cultures are on the basis of their functioning and results either in whole or in part praiseworthy or blameworthy. But if culture is essentialized, treated as if it were race or gender, then the observer who reports what he sees can appear bigoted. But on what grounds is it rational to assume that all cultures are equal?

* * *