It’s striking how social media users don’t bother seeking out those who actually understand the subject before making a big deal out of the fact that Pretti had been disarmed by Border Patrol before being shot and killed by other officers, or the fact that so many shots were fired. That he was disarmed is largely irrelevant. Emptying a magazine into a body is unusual in law enforcement. What matters is the context and the reasonable person standard.

The US Supreme Court has established that police use of deadly force is governed by the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable seizures. The leading case is Tennessee v Garner (1985), which held that an officer may not use deadly force against a fleeing suspect unless there is probable cause to believe the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others. This decision limits police use of deadly force.

The Court refined the framework outlined in Garner in Graham v. Connor (1989), ruling that claims of excessive force are evaluated under an “objective reasonableness” standard. Courts ask whether a reasonable officer in the same situation would have believed the level of force was necessary, rather than relying on the officer’s subjective fear or intent. Factors include the severity of the alleged crime, whether the suspect posed an immediate threat, and whether the suspect was resisting.

Courts also consider situational factors, such as the suspect’s behavior and the appearance of objects. The officer must reasonably believe the suspect poses a serious risk of death or bodily harm. At the same time, courts recognize that officers make split-second decisions under high stress and give deference to those judgments. This is why shootings of suspects holding ambiguous objects are often legally justified if the officer’s belief is reasonable.

Other cases clarify the standard further. Scott v Harris (2007) confirmed that deadly force can be reasonable when a suspect’s actions pose an imminent danger to others. Kingsley v Hendrickson (2015) reaffirmed that excessive-force claims for pretrial detainees are judged by objective reasonableness, without requiring proof of the officer’s subjective intent.

Taken together, these cases establish that deadly force is constitutionally permissible when a reasonable officer would perceive an imminent risk of serious harm or death, based on the totality of the circumstances. Courts evaluate this from the perspective of officers at the scene, recognizing that decisions often must be made in tense, rapidly evolving situations. Crucially, the belief must be objectively reasonable; if multiple officers act together, reasonableness is generally assumed.

When people ask why officers empty their magazines, the answer lies in psychology, situational dynamics, and training, rather than a deliberate desire to overshoot. In high-stress encounters, officers must react within fractions of a second to perceived life-threatening threats.

Adrenaline and fear may cause the first shot to miss or prompt continued firing until the threat appears neutralized. Stress triggers tunnel vision, an elevated heart rate, and reduced accuracy, often leading to instinctive, repeated firing. Studies show that even highly trained marksmen will fire multiple rounds under extreme stress.

Officers do not have the luxury of reviewing the scene from multiple angles. To illustrate this, I ask students to think of a boxing match. We often watch boxers and wonder why they don’t punch when openings appear or why they don’t avoid telegraphed blows. But that judgment is made from the armchair perspective. Imagine instead being the boxer: you’re getting hit in the face and body, the crowd is screaming, and your body is reacting from muscle memory.

Now imagine being a police officer confronting a man on an icy street in sub-zero temperatures. The armed detainee is not following commands. Multiple civilians are resisting. Bystanders are yelling, whistling, and honking. You look down and see the detainee’s holster is empty—you did not see the other officer remove the weapon. The suspect is rising. If you do not assume that there is a weapon and that the man may act belligerently, you, your fellow officers, and nearby civilians may be shot or injured. You don’t have time for a careful assessment. Officers are yelling, “Gun!” You neutralize the threat.

It’s tragic, but not uncommon. More than 1,000 civilians are killed by police officers every year. Almost none of the shootings are challenged, not because of deference to policing, but because of the reasonableness standard.

Training emphasizes stopping a threat completely, because even wounded assailants can remain dangerous. If the suspect is still moving, reaching for something, or appears aggressive, officers continue firing until the threat is eliminated. Officers are trained to focus on the center mass, aiming for the torso to stop a threat efficiently. Hitting a moving target in dynamic situations is difficult, which naturally leads to multiple shots to achieve incapacitation. You don’t aim for the legs. You aim for the chest.

Pretti’s death is tragic, but it is a textbook example of a good shoot (as was the Renee Good case). Pretti could have avoided his fate had he cooperated with the officers—even better, had he not been there at all (a parent warned him about the risk he was taking). This is the message progressives should be sending to their constituents: do not interfere with federal law enforcement operations.

But Progressives make the opposite argument, and this endangers lives. Condemning law enforcement for enforcing the law and predictable actions based on confusion and training increases the likelihood that protestors will resist lawful commands in the future, thus endangering their lives and the lives of others.

It is the height of irresponsibility—if we don’t assume a darker impulse (which, frankly, for many on that side, I do)—not to explain what happened in Minneapolis over the weekend was the consequence of Prett’s actions and is entirely avoidable if he had stayed home—or, if one chooses to bring a gun to a protest action, follow the commands of law enforcement.

This last point is crucial to grasp. I’m a big proponent of firearms. But I don’t understand why Pretti would bring a gun to a protest, given his purpose that day. Who would he have to shoot other than law enforcement? He wasn’t going to shoot other protestors. He was there as a protester—ostensibly, as the evidence now suggests (I will follow up on this in this afternoon’s essay.)

The Pretti case is not at all analogous to the situation involving Kyle Rittenhouse, who brought a firearm to Kenosha in the summer of 2020 to protect himself from rioters, not from law enforcement. Rittenhouse had no intent to shoot law enforcement. When law enforcement showed up, he tried to surrender. They waved him away (he later turned himself in). Rittenhouse’s actions are exactly how an armed civilian is supposed to act when confronted by law enforcement.

Progressives condemned Rittenhouse for bringing a gun to a protest and were shocked when he was acquitted. Until a few days ago, they still condemned his actions on that day. Now they feign support for citizens carrying arms to protests. They think they have conservatives and liberals cornered for hypocrisy. But the hypocrisy is obviously on their side. Had Rittenhouse been shot by police, I guarantee you that progressives would have said that he had it coming. Had he been convicted, they would have praised the jury.

So which is it, progressives? Should protesters bring firearms to protests or not? The answer to that question depends on whether the weapon is potentially used on violent protesters or whether it’s potentially used on law enforcement.

Remember the National Guard soldiers shot by an assassin in Washington, DC? Who did progressives blame? Not the assassin. They blamed Trump for deploying the National Guard on the streets of DC. They’re blaming the violence in Minneapolis and St. Paul on Trump. This is now a reflex. Progressives blamed the assassination of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson by Luigi Mangione on the dead man. They blame the assassination of conservative youth leader Charlie Kirk by Tyler Robinson on the dead man.

If the killing of National Guardsmen is justified by their presence on the streets of Washington, DC (or any other American city), then the killing of any law enforcement officer is justified by his presence. Isn’t that what they’re saying? Pretti is dead because ICE is in Minneapolis. ICE must leave to end the violence.

Progressives mean to turn America into a lawless country—as long as their comrades are the lawless ones.

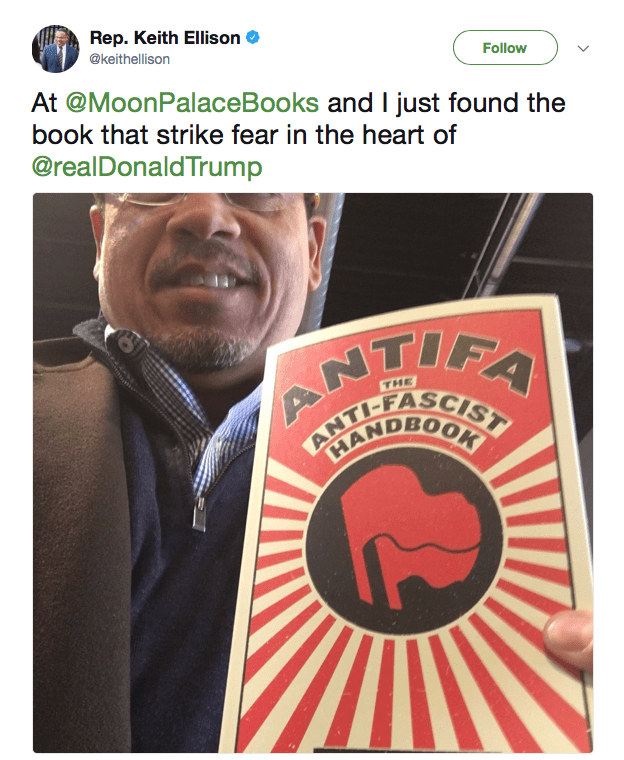

The ruse worked. Progressives got their way. Trump caved. The Administration is sending Border Patrol commander Gregory Bovino packing. They even appear ready to allow the state to investigate Petti’s death—this in a state whose attorney general, Keith Ellison, endorses Antifa. One need only reflect on the fate of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin and his three comrades to see how justly that state treats law enforcement. Governor Tim Walz appointed Ellison as special prosecutor in the George Floyd case.