“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” —Preamble to the United States Constitution

Today, we mark the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr. Whatever his personal failings, King loved America enough to hold it accountable to its ideals, insisting that equality and freedom are not abstract aspirations but binding commitments. The torch of his dream helped guide the country out of contradiction. An assassin’s bullet made sure he did not live to see America thrown back into it.

Standing at the Lincoln Memorial, King reminded the nation that the American experiment is measured not by its words alone, but by whether it fulfills its promises to all its people. King’s dream did not reject America—it called the country to become itself, to judge individuals not by their identities, but by their character. The man came bearing republicanism, the belief that a nation’s power derives from the People, exercised through representative government, with citizens’ virtue and the common good as its foundation.

The Democratic Party stands King on his head. Indeed, the party of slavocracy and Jim Crow subverted America’s promise from its inception. The party now openly channels anti-American sentiment. As the Good Book teaches us, God places challenges or adversaries—sometimes symbolized as Satan—in a nation’s path to test it. These obstacles are meant to push the people to confront injustice, overcome both external and internal evils, and achieve a more righteous, perfected nation.

The answer to the polling question asking whether ICE should be abolished is a proxy for the deeper question: Shall we have open borders? A CNN poll finds that more than three-fourths of Democrats effectively want open borders—hardly unexpected. Only a little more than one in ten Republicans do.

But there is an even more profound question underlying that one: whether one believes a nation should have borders at all, which is another way of asking whether there shall be nations. The answer to this question is everything.

The divide between Democrats and Republicans is wide and unbridgeable. It has always been substantial, to be sure, but the gulf between the parties today is as deep as it was when the nation stood at the threshold of the Civil War in the late 1850s. The parties represent two different conceptions of the future: either an American future or a future without America.

This is tragic, given that we are celebrating the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence—the document that put absolutism and monarchy on notice. Instead of a year spent reflecting on the greatness of the American Republic, we must devote our energies once again to confronting forces that seek to disunite us. I worry that the patriots no longer have the energy required to stand up for the nation. I fear that decades of emasculation and America-bashing have rendered too many men impotent. This moment will test whether America still has the stones to overcome obstacles thrown in its path.

I have been arguing since 2020—when it became obvious to anyone with open eyes and ears that the country was in deep trouble—that the real divisions in politics are not superficial or partisan, but profoundly moral and philosophical: populism versus progressivism, nationalism versus transnationalism, individualism versus collectivism, democracy versus technocracy, and republicanism versus corporatism.

The opposing sides of these binaries together constitute a larger binary: American versus anti-American. Each pair marks an axis of political identity. Together, they form a political grammar: to speak in one term is already to reject the other; to locate oneself on one end is to be positioned against its opposite.

These are not neutral preferences but rival camps. One cannot inhabit both sides at once. These are not positions along a spectrum but lines of division—populism or progressivism, nationalism or transnationalism, individualism or collectivism, democracy or technocracy, republicanism or corporatism.

This follows from the three foundational laws of logic.

The Law of Identity holds that whatever exists has a determinate identity; a thing is itself and not another (this is why, e.g, the transgender individual is an impossible individual).

The Law of Noncontradiction holds that the same thing cannot both be and not be at the same time and in the same respect; a claim cannot simultaneously affirm and deny the same predicate. For example, the alleged fusion of populism and progressivism is a falsehood.

The Law of the Excluded Middle establishes bivalence: every proposition is either true or false, with no third option between them. In short, either the people govern themselves, or they are governed by something else.

Consider what Democrats want (they confess this openly): big, intrusive government; control over the socialization of our children; administrative and corporate control over our bodies and choices—the medicines we take, the foods we eat, the media we consume, the words we say; the privileging of selected ethnic, racial, and sexual minorities over the rights of the individual; a disarmed population; bargain-basement wages for workers; the diminishment of Western culture through the imposition of multiculturalism; and global governance.

There is a word for what Democrats want: authoritarianism. Indeed, there is more than one word for it: totalitarianism, serfdom—many words apply. However, the following words appear in the Party literature and pronouncements only as glittering generalities: autonomy, democracy, freedom, and justice. Their plans will cancel the substance of each of them in action. In fact, as the record of history makes clear, they have already weakened all of these.

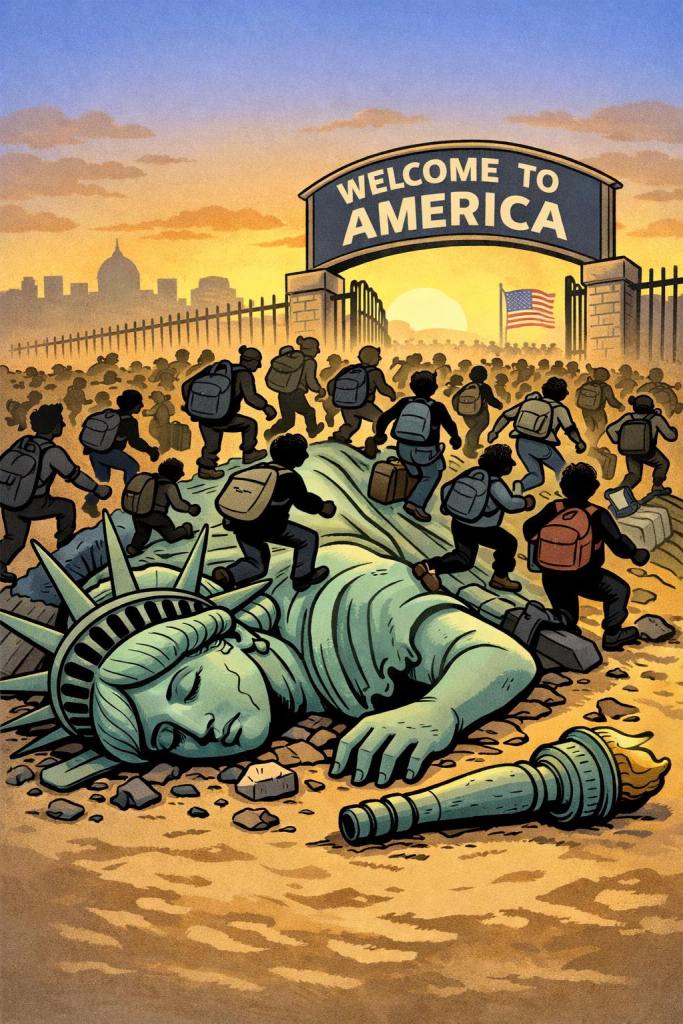

The Statue of Liberty was conceived by French abolitionist Édouard René de Laboulaye and designed by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi as a celebration of liberty and republican government, a tribute to the American Revolution, and a symbolic nod to the end of slavery after the Civil War. Its full original name makes this clear: “Liberty Enlightening the World.”

Lady Liberty is a republican symbol. She had nothing to do with immigration. In France, the female personification of republican liberty is called Marianne. Emerging during the French Revolution, Marianne embodied the ideals of liberté, égalité, fraternité (liberty, equality, fraternity)—a civic, secular figure representing the sovereignty of the people rather than monarchy or empire.

This shared republican imagery forged a deep symbolic connection between France and the United States: when France gifted Liberty Enlightening the World to America in the nineteenth century, the statue fused these traditions—Marianne’s revolutionary spirit with America’s own Lady Liberty—affirming a transatlantic commitment to republican self-government, popular sovereignty, and the universal aspiration toward freedom. America’s own Columbia guided the founding and expansion of the Republic.

Like Columbia in the United States, Marianne served as a symbolic guide for a new republic, appearing in art, coins, and public buildings as a reminder that the nation derived its authority from its citizens. Its torch burned out; France lost its way. We mustn’t allow the nightmare antithesis of progressivism extinguish the flame of liberty in America.

Those who would put out liberty’s light have been at it for a long time. In 1903, transnationalists—cultural figures, philanthropists, and writers who elevated the message of an 1883 poem by Emma Lazarus, “The New Colossus”—repurposed the statue, mounting a plaque with Lazarus’ poem inside its pedestal. The poem was not commissioned as the statue’s mission statement. It was not displayed on the statue at the dedication (which occurred decades earlier). The plaque reflected Lazarus’s personal humanitarian views, not the views of the nation.

What did the country think? A few decades later, in the 1920s, the nation, with populists and nationalists—in a word, patriots—leading the way, would sharply restrict the flow of immigration for more than forty years. The nation needs another forty years. The antithesis smears the patriots with invectives—“anti-immigrant,” “bigot,” “chauvinist,” “intolerant,” “nativist,” “racially prejudiced.” To hell with the antithesis.

Progressives are going full fascist right before our eyes. The street elements leverage anarchist and communist symbology, but the function is corporate statist. (Remember, Hitler called his politics “socialist,” too.) The neoconfederate attitude among Democratic Party leaders is the mark of the managed decline of the Republic. Those in the streets and those in the suites seek either the dissolution of the Union or a one-party state. The racist element is obvious in anti-white bigotry. The opposite of the American thesis could not be more explicit.

Whatever the problems one may have with the Republican Party—and I have a few—the choice in November 2026 is clear if one wishes to keep the United States of America. This does not mean we cannot have a system with multiple political parties. It does mean that the core of each party must have the foundational principles of the Republic at the core of their respective platforms. A stable constitutional republic can tolerate neither a movement nor a party that stands in the way of American greatness.