“To sum up, what is free trade, what is free trade under the present condition of society? It is freedom of capital. When you have overthrown the few national barriers which still restrict the progress of capital, you will merely have given it complete freedom of action. So long as you let the relation of wage labor to capital exist, it does not matter how favorable the conditions under which the exchange of commodities takes place, there will always be a class which will exploit and a class which will be exploited. It is really difficult to understand the claim of the free-traders who imagine that the more advantageous application of capital will abolish the antagonism between industrial capitalists and wage workers. On the contrary, the only result will be that the antagonism of these two classes will stand out still more clearly.” –Karl Marx, “On the Question of Free Trade” (1848)

I’ve come down on the side of protectionism. No news here. Many of my Marxist colleagues disagree. Some of the disagreement is kneejerk reaction to Trump. As with progressives, Trump derangement syndrome is rampant on the socialist left (see the CPUSA and the possible end of May Day). But some of it is accelerationist desire to hasten capitalism’s demise, which rightwing libertarians would do well to note; Marxists are right about free trade: it is destructive to capitalism.

Marxists don’t oppose protectionism because tariffs hurt working people—on the contrary: they oppose protectionism because it protects the worker’s standard of living. National capitalism forestalls the eventuality they desire, namely the socialist revolution and the establishment of world communism, and suffering towards that end is acceptable. The fate of workers is thus sacrificed on the altar of political ambition.

What did Karl Marx have to say about the matter of free trade and protectionism? Fortunately, we need not hunt through the corpus of his work for clues about his views. In 1848, before the Democratic Association of Brussels, Marx delivered a speech in which he makes his position on the protection versus free trade debate explicit. He comes down on the side of free trade. That’s because protectionism is, in relative terms to be sure, better for workers. Sounds paradoxical, I know, but stay with me here.

In his speech “On the Question of Free Trade,” Marx critiques not just the policies of his day, but the deeper economic structure underpinning them. Far from a technical economic treatise (he flashes expertise here and there), Marx’s speech uses the question of tariffs and trade to expose the contradictions of a society divided by class. His core thesis: free trade does not liberate workers; rather, it liberates capital. In doing so, it accelerates the internal contradictions of capitalism and hastens the conditions for revolutionary change.

So determined is Marx to see capitalism do itself in, he comes down on the side of free trade—not because he believes it helps the worker, but precisely because it makes the worker’s condition worse. “In general, the protective system of our day is conservative, while the free trade system is destructive,” Marx argues. “It breaks up old nationalities and pushes the antagonism of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie to the extreme point. In a word, the free trade system hastens the social revolution. It is in this revolutionary sense alone, gentlemen, that I vote in favor of free trade.” I confess I do not share his commitment to this end. Not at the suffering of fellow Americans. And given George Orwell’s observations, I am not sure I agree with the end.

Today’s free trader—the globalist—also seeks a revolution, but not a proletarian one. Communism is not the end sought in the ambitions of the global elite. Rather, it’s a top-down revolution, one that aspires to a post-labor economy governed by technocrats and the oligarchy they serve. The capitalist mode of production is reaching a terminal point: the elimination of necessary labor via artificial intelligence and robotics. But rather than allow this to necessitate a communist reorganization of distribution based on need, the global elite aims to preserve its privilege by overseeing a neo-feudalist world order, in which a shrinking laboring class is rendered permanently dependent and expendable, managed by a new aristocracy.

Thus, those of us for whom workers are the choice of comrades, and who care about their wellbeing, must advocate for the system that is in their best interests—even if it is one of the two types of capitalism Marx critiques. Protectionism is lesser of two evils in this regard.

While Marx rejects protectionism for its failure to bring about revolution, he openly acknowledges that it is better for workers than free trade. Realizing the implications of his argument, Marx hastens to deny that he is defending tariffs. “Do not imagine, gentlemen,” he says, “that in criticizing freedom of trade we have the least intention of defending the system of protection.” Yet, he admits that the “protectionist system” is “a means of establishing large-scale industry in any given country,” which liberates man from backwardness. This is an important concession: protectionism enables the bourgeoisie to challenge the aristocracy and modernize—conflicts and outcomes that advance the material position of workers under capitalism, while limiting the reach of capitalism globally.

Marx tells his audience that economic “freedom” is never neutral. Free trade, in practice, means the freedom of capital to move unimpeded in search of profit, not the freedom of labor to live decently. “It is freedom of capital,” Marx declares. “So long as you let the relation of wage labor to capital exist,” he argues, “there will always be a class which will exploit and a class which will be exploited.” True, but under the regime of free trade, their exploitation will be much greater.

For Marx, removing trade barriers removes an illusion. “Let us assume for a moment,” he posits, “that all the accidental circumstances which today the worker may take to be the cause of his miserable condition have entirely vanished, and you will have removed so many curtains that hide from his eyes his true enemy.” Free trade exposes capitalism for what it is—a system of class domination. But it does nothing to mitigate the suffering of the working class. Marx admits that free trade intensifies the misery of the worker. It also moreover subordinates capital. Freeing capital from national boundaries “will make [the worker] no less a slave than capital trammeled by customs duties.” Better capitalism is subordinate to nations than to be free of them.

Free trade does not liberate the worker; it simply accelerates the process by which labor is immiserated, and capital is accumulated, concentrated, and consolidated. As Marx puts it bluntly: “Gentlemen! Do not allow yourselves to be deluded by the abstract word freedom. Whose freedom? It is not the freedom of one individual in relation to another, but the freedom of capital to crush the worker.” Do Marxists really want to the see the worker crushed for the sake of a pipe dream? Worse—for something that may cast them into a lower level of Hell? It’s not as the world communists created was better than the world capitalists made.

For Marx, liberal claims that free trade allows each country to specialize in its “natural” production role are disingenuous. This is a critique of the comparative advantage argument free traders have used for centuries Marx is equally contemptuous of the idea that free trade fosters global solidarity. “The brotherhood which free trade would establish between the nations of the Earth would hardly be more fraternal,” Marx writes. “To call cosmopolitan exploitation universal brotherhood is an idea that could only be engendered in the brain of the bourgeoisie.” Free trade globalizes class antagonisms—it does not abolish them. “All the destructive phenomena which unlimited competition gives rise to within one country,” Marx notes, “are reproduced in more gigantic proportions on the world market.”

Marx also dismantles the claim that cheap goods benefit workers: “You say, ‘Here is a law which raises wages by lowering the price of the things necessary for life.’ Yet the cheapness of commodities is but a momentary palliative, not a cure.” Far from a cure. “When less expense is required to set in motion the machine which produces commodities … labor, which is a commodity too, will also fall in price … and this commodity, labor, will fall far lower in proportion than the other commodities.” This illusion, he argues, leads to a cruel outcome: “The working class will have maintained itself as a class after enduring any amount of misery and misfortune, and after leaving many corpses upon the industrial battlefield.”

If wheat prices and wages are both high, Marx explains, workers can save a little on bread and use those savings to enjoy other goods. But when bread becomes very cheap, and wages drop as a result, there’s hardly any room left for savings to spend on other things. When it costs less to operate the machinery that produces goods, the cost of maintaining the worker—the human component of that machinery—also decreases. Since all goods are cheaper, and labor is considered a good, too, the value of labor drops, and it tends to fall even more sharply than the prices of other goods. Free trade is a race to the bottom.

Marx warns that economists will respond by acknowledging that competition among workers, which doesn’t lessen under free trade, pushes down wages along with falling prices. However, the cheaper goods will lead to higher consumption, which in turn boosts production, thereby increasing the demand for labor and eventually raising wages. This reasoning boils down to the belief that free trade enhances productive capabilities. As industry expands and wealth and productive capacity grow, labor demand and wages should theoretically increase. The best scenario for workers, it’s argued, is when capital is growing. If capital stagnates, industry shrinks, and workers suffer most, losing their livelihoods even before capitalists do.

But even when capital grows—the best case for workers—the outcome is only relatively better. The growth of capital leads to its accumulation and concentration, which brings more division of labor and reliance on machinery. This strips laborers of their specialized skills and replaces them with easily replicable tasks, increasing competition among workers.

This is basic to the capitalist dynamic. As the division of labor elaborates, a single worker can do the work of several, intensifying competition. Machines magnify this effect even further. The expansion of capital compels large-scale production, pushing out smaller producers and turning them into wage laborers. Meanwhile, as returns on capital shrink, small investors can’t live off their dividends and are also driven into the labor market, adding to the growing working class.

As productive capital continues to rise, it increasingly produces for markets without knowing actual demand (the problem of overproduction). Supply begins to dictate demand, leading to frequent and severe consumption crises. Each crisis accelerates capital centralization and expands the proletariat. Ultimately, as capital grows, worker competition grows even faster. Labor becomes less rewarding for all and more burdensome for many.

In modern terms, this dynamic obtains: as productivity rises—often through automation, outsourcing, and rationalization of labor—real wages for workers stagnate or decline (relative to productivity) and labor is made redundant. Policymakers and employers point to cheaper consumer goods as compensation, arguing that workers are better off because they can buy more with less. They tell the worker that tariffs bring higher prices that workers cannot afford. But this masks the fact that the share of value created by workers increasingly flows to capital, not labor.

Marx’s insight remains salient: cheap commodities are not a gift to the worker—they are a mechanism through which capital justifies the degradation of labor’s share in the economy. The availability of inexpensive goods is used ideologically to mask the deeper economic injury done to workers through wage suppression.

Marx is unwavering in his belief that protectionism is insufficient for advancing the proletarian struggle. “One may declare oneself an enemy of the constitutional regime without declaring oneself a friend of the ancient regime.” For Marx, both free trade and protectionism serve capital in different ways. But for those of us who do not seek revolution, who do not believe communism lies ahead, who do not wish to accept the immiseration of workers for the sake of an uncertain future, or do not seek this future, Marx’s argument flips in protectionism’s favor.

Marx makes it clear that the destructive nature of free trade is its chief appeal to revolutionaries. This is a crucial moment in the speech: “It breaks up old nationalities,” he declares. It “pushes the antagonism of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie to the extreme point.” But what if man does not want to dissolve nationalities, to break the bonds of culture, tradition, and sovereignty? What if he wishes to preserve the nation-state, the rule of law, and democratic control over society? The things he and his comrades cherish dissolve under globalization.

And what if he does not desire to see poor nations suffer for the sake of globalism? Then he understands what the globalists pretend they do not. “If the free-traders cannot understand how one nation can grow rich at the expense of another, we need not wonder,” Marx observes, “since these same gentlemen also refuse to understand how within one country one class can enrich itself at the expense of another.” Why would workers wish to see class antagonisms projected upon the planet? And to the extent that has already, why would he want to see them entrenched—at his expense, no less.

For Marx, the intensification of contradiction is the goal. For the patriot, it’s a danger. The collapse of domestic manufacturing, the offshoring of production, the destruction of rural economies, and the rise of post-national capital—all of this has indeed hastened inequality and alienation; but it has not, as Marx hoped, led to a worker-led revolution. It has led instead to cultural decay, political instability, and oligarchic control. All the immunities and privileges Americans claim as their birthright—free speech, religious liberty, privacy, and the vote—will be wiped away with the end of the modern nation-state.

All those insisting that Marx was for free trade, does that mean that those on left should be, too? Are we taking marching orders from a dead man? Why not acknowledge his insight instead? Marx’s text makes clear that if revolution is not your goal, if you are uncertain that humanity will transcend capitalist relation, or worried about what barbarism awaits, free trade is not your friend. Transnationalism and multiculturalism are not your politics. For those committed to the welfare of workers, the preservation of community, and the defense of democratic self-government, protectionism becomes the only defensible position—not because it abolishes class conflict, but because it slows capital’s most destructive tendencies and gives nations room to defend a way of live, protect labor, and uphold sovereignty.

Marx understood the power of capitalism to transform the world, but he underestimated its capacity to survive by managing, rather than resolving, its crises—financialization, globe-trotting, etc. He was right about where free trade take us. He was wrong about embracing the outcome. And so, in the absence of worker revolution, or in the face of a fate worse than now, we must choose the form of capitalism that does the least harm and offers the most hope for the dignity and security of the working class. That is not the free trade regime of the transnational elite; it’s the protection of national economies and the defense of domestic industry, and especially the men and women who produce value with their labor, who uphold the community, who protect their families.

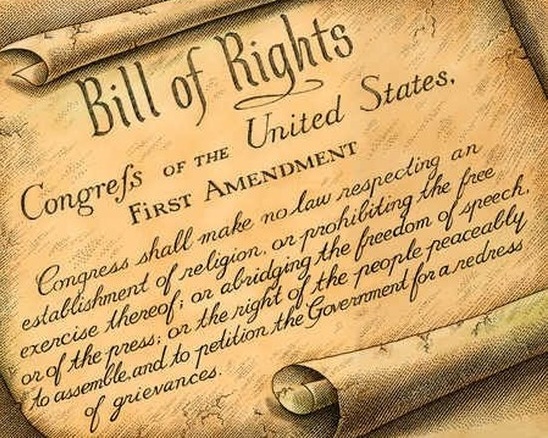

For those who still desire life under communism, the accelerationist stance articulated by Marx’s speech presumes communism inevitably follows the demise of capitalism. But in other writings, he does not make this presumption. While Marx often spoke of capitalism’s downfall and the rise of communism, he did not believe this outcome was historically inevitable. The materialists conception of history is not teleological; it identifies tendencies and contradictions within capitalism—such as crises of overproduction and the intensification of class struggle—that could lead to revolutionary change. Only through conscious political action by the working class could a better world be made. What would better empower the worker? A one world government beyond the reach of eight billion? Or a democratic republic with universal suffrage and a First and Second Amendment?

Marx rejected utopianism and eschatology, insisting that the future is not predetermined but shaped by material conditions and human agency. A charitable reading of his support for free trade is that it is not grounded in faith in progress, but rather in a strategic acceleration of contradictions that might expose capitalism’s exploitative core. Communism, for Marx, was a possibility—not a prophecy. But that’s risky. And nowhere in sight. Moreover, we should ask ourselves whether that is the world we want—or whatever else comes instead. Whether you fear communism or barbarism, free trade will take us to one or the other or something unimaginable. We must therefore oppose it.

“Thus, of two things,” Marx warns: “either we must reject all political economy based on the assumption of free trade, or we must admit that under this free trade the whole severity of the economic laws will fall upon the workers.” For Marx the accelerationist, he hopes we admit to the latter. I reject political economy based on free trade. To be sure, the world has become substantially globalized. But we cannot stop the advance of transnationalization, or reverse its effects, until we understand the intent and the machinations of its operatives and oppose them.

It therefore becomes incumbent upon those who find wisdom in Marxian thought to align with the populist-nationalists who include the fortunes of workers in their political economic schemes. The choice is between capitalism and neofeudalism. Simply put, will we have liberty or slavery?

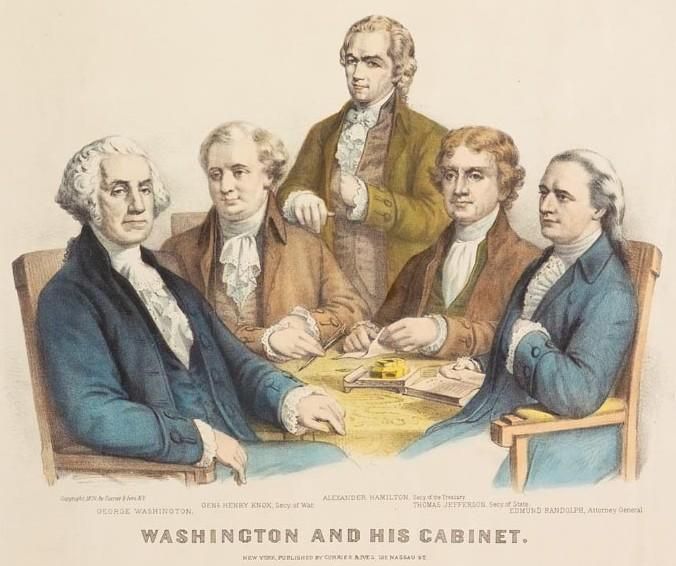

Before leaving this essay, I need to explain in more depth Marx’s critique of political economy and its relationship to Alexander Hamilton’s vision of the American System. It is Hamilton’s American System that provides the left with the radical case for protectionism. By left, I mean here liberals and democrats who stand with the working class and rural communities over against the New Left (anti-Enlightenment proponents of identity politics) that serves the interests of the transnational corporate class.

I have written about this before, but rather than send you other essays, I will explain it here. Marx’s critique of capitalism centers on an internal contradiction that drives both its dynamism and its eventual crisis. Capitalism, in Marx’s view, is based on the extraction of surplus value from labor (wage and slave). As the father of liberalism John Locke understood, labor is the source of value in production, and capitalist profit arises from the difference between what workers are paid (variable capital) and the total value they produce. Surplus value is realized as profit when goods are sold in the market.

However, in seeking to maximize profit, the capitalist is driven to maximize surplus value by minimizing labor costs—either by suppressing wages or replacing labor with machinery (increasing the organic composition of capital). While this raises the rate of surplus value, it undermines the capacity of workers to consume the very goods they produce. This creates a contradiction: surplus value is generated in production that cannot be fully realized in circulation due to insufficient demand (overproduction). This tension contributes to capitalism’s systemic instability (boom and bust and its long waves) and, ultimately, its tendency toward crisis.

This contradiction is manifest in and confirms Marx’s formulation of the falling rate of profit amid the increasing rate of exploitation. As capitalists substitute machinery for labor, the amount of surplus value generated per unit of capital invested begins to fall, since only labor creates new value. At the same time, the exploitation of labor intensifies. The rate of exploitation—measured as the ratio of surplus value to variable capital (s/v)—rises, but so does the inability of the market to absorb the output of increasingly productive but poorly paid labor.

Though Alexander Hamilton did not share Marx’s analytic framework or revolutionary aims (Marx was not yet born), he anticipates it. Hamilton recognizes elements of this contradiction in his efforts to craft an economic strategy for the young American republic. In his 1791 Report on the Subject of Manufactures, Hamilton argues for a strong industrial base supported by tariffs, subsidies, and public investment. His objective was not only national independence but also economic stability through the balanced development of manufacturing alongside agriculture. Hamilton understood that, left unchecked, capitalists would import cheap goods from other industrialized and industrializing nations, undermining domestic production and driving down wages. To Hamilton, a purely laissez-faire system would erode the productive capacity of the nation and leave it dependent on foreign powers. Thus Hamilton was an early theorists of dependency theory.

Hamilton’s vision prefigures the problem that Marx would later formalize: the unchecked pursuit of profit can destabilize the very conditions of profitable production. Unlike Marx, Hamilton sought to resolve this contradiction not by abolishing capitalism, but by guiding it through protective and strategic policy. He believed that the state had a critical role to play in sustaining a productive domestic economy in which wage laborers could remain both producers and consumers.

Central to Hamilton’s plan was the idea of productivity. He viewed national strength as closely tied to improvements in productive efficiency. However, he did not account for the distributional consequences of that productivity in exactly the way Marx did. For Marx, productivity gains under capitalism do not benefit workers proportionally. They serve to increase the surplus appropriated by capital while wages remain stagnant or decline. Thus, productivity without redistribution intensifies exploitation. The capitalist benefits from an expanding rate of surplus value, but the system becomes increasingly unable to realize profits through market exchange due to weak demand. This is a problem that governments have been left to overcome.

This theoretical insight remains highly relevant in the age of globalization and can be tracked empirically through tools such as the Annual Survey of Manufactures (ASM) conducted by the US Census Bureau. The ASM collects data on employment, wages, capital expenditures, and value added—data that can be used to analyze contemporary forms of Marx’s exploitation metric. By comparing total wages (variable capital) with profits and other forms of gross operating surplus, one can observe whether productivity gains are translating into improved conditions for labor or merely higher returns to capital.

In the decades following the mid-twentieth century, US manufacturing productivity rose sharply while real wages stagnated. At the same time, firms increasingly offshored production or imported goods produced with cheap foreign labor, much as Hamilton had feared. This is the result of free trade for all the reasons Marx explains in his speech. This trend not only weakens domestic labor but also hollows out the consumer base necessary to sustain aggregate demand. Here, the contradiction becomes evident: firms achieve higher surplus value through cost-cutting, but face diminished capacity to realize that value in the market because of suppressed wages and deindustrialization.

Hamilton’s advocacy for protectionism can be seen, then, as an attempt to moderate this contradiction within a national framework. He sought to create a self-reinforcing loop between domestic production, decent wages, and national consumption. Globalization, in contrast, bypasses this loop, facilitating what Marx saw as an acceleration of capitalism’s internal crisis. When production is outsourced and wages are driven down domestically, the conditions for stable consumption—and thus for the realization of surplus value—are undermined. Global labor arbitrage functions as a modern form of wage suppression and labor displacement, replicating the contradiction on a global scale.

As we have seen, Marx welcomes this development—not because it was just, but because it hastens capitalism’s internal unraveling. In his support for free trade, Marx argues that globalization exposes and intensifies capitalism’s contradictions by eroding national boundaries and deepening class antagonism. In his words, free trade “breaks up old nationalities and pushes the antagonism of the proletariat and bourgeoisie to the extreme point.” Where Hamilton sought to contain and manage capitalism’s contradictions within the nation-state, Marx hopes to see them drive revolutionary change on a global scale. This can only be obtained by releasing the beast from its protectionist chains.

As quoted above, Marx tells his audience: “In a word, the free trade system hastens the social revolution. It is in this revolutionary sense alone, gentlemen, that I vote in favor of free trade.” Because the free trade system is bad for workers, I vote in favor of protectionism. I stand with Hamilton on this issue. Reflecting on this, Marx’s argument causes me to reconsider whether the proletariat is Marx’s real choice of comrades, or whether his vision of a communist future is to be sought at the risk of barbarism.