In contemporary universities, programs such as Women’s and Gender Studies or Race and Ethnic Studies have become well-established parts of the academic landscape. These programs are often justified as correctives to historical exclusions, offering focused attention to groups whose experiences were previously marginalized within traditional disciplines. Yet, from a sociological perspective, there’s a deeper question worth examining, namely, whether academic programs organized explicitly around identity can genuinely sustain heterodox thought and robust internal critique.

My concern is not that such programs lack intellectual seriousness (although they often do), nor that the topics they address are illegitimate. Rather, it’s that programs defined by identity categories tend, culturally and structurally, to function as representational spaces for particular subgroups within the population. In doing so, they risk prioritizing advocacy, affirmation, and protection over critical inquiry. When a program implicitly understands itself as representing a community—rather than studying a phenomenon—it becomes difficult for that program to tolerate viewpoints that are perceived as threatening to that community’s self-understanding.

This dynamic is often described in terms of “safe spaces.” While the original intent of safe spaces may have been to protect students from harassment or overt hostility, the concept has increasingly expanded to include insulation from critical perspectives that challenge foundational assumptions. In such an environment, heterodox views—whether theoretical or normative—can come to be interpreted not as contributions to scholarly debate but as moral or political threats. The result is a narrowing of acceptable discourse within the very programs that claim to be dedicated to critical thinking.

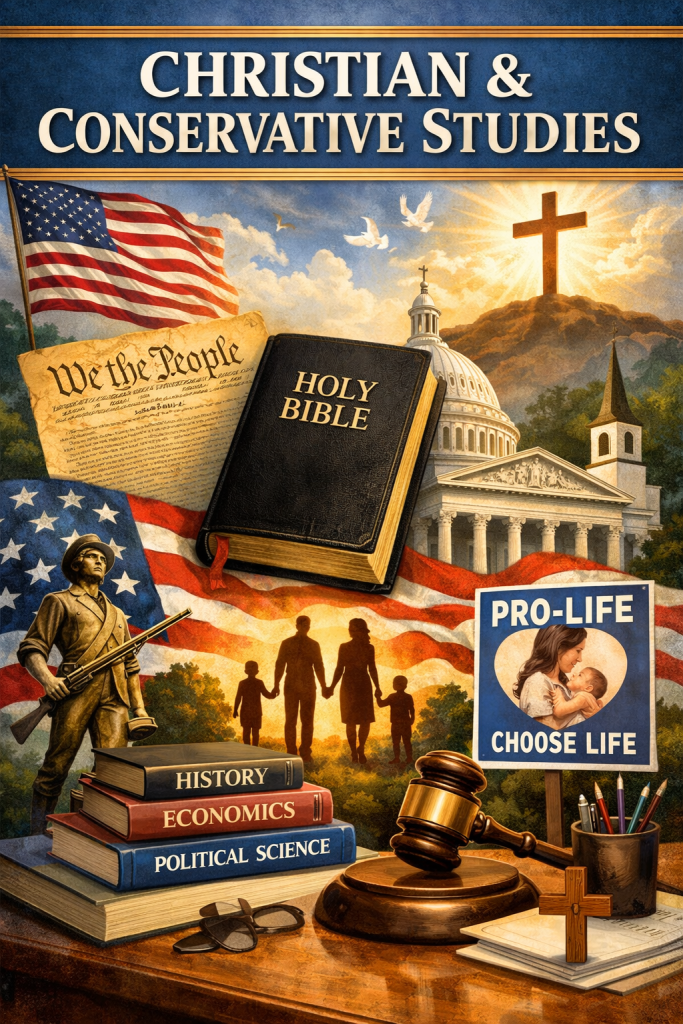

To clarify this concern, consider an argument by analogy. Imagine a university establishing a program called Christian and Conservative Studies. Such a program would almost certainly be understood as pandering to a particular identity-based constituency, namely conservative Christians. If the program were genuinely critical—if it rigorously examined Christianity as a belief system, conservatism as a political ideology, and the historical consequences of their influence—it would likely provoke strong objections from the very community it ostensibly represents. Conservative Christian students would perceive the program as hostile rather than affirming, and enrollment pressure, donor backlash, or public controversy would follow.

Conversely, if the program were designed to be attractive to conservative Christian students—to function as a “home” for them, a safe space for a distinct minority in the humanities and social sciences—it would almost certainly avoid sustained critique of core beliefs and commitments. In that case, the program would not serve as a genuine locus of critical inquiry but rather as a protective ideological enclave, reinforcing shared assumptions and discouraging internal dissent. The very logic that makes the program viable as an identity-affirming space would undermine its capacity for rigorous critique.

The analogy is instructive because it reveals a structural symmetry. If we can readily see why a Christian and Conservative Studies program would struggle to maintain intellectual independence from the identity it represents, then we should at least be open to the possibility that Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies or Race and Ethnic Studies face a similar tension. The issue is not the political valence of the identity in question but the institutional logic of representation itself. This parallel is reinforced if one imagines a Christian and Conservative Studies program organized as a space to aggressively critique the worldview of conservative Christians. It’s inconceivable that a public university would organize programs around race and gender in which woke progressive ideology and queer theory were the targets of withering criticism.

Traditional academic disciplines—such as economics, history, philosophy, or sociology—are organized around methods, questions, and objects of study rather than affirming particular identities. At least ostensibly. This organizational structure makes it easier, at least in principle, to sustain internal disagreement and theoretical pluralism. I say in principle because policing around gender in traditional disciplines is intense. As a sociologist, I’m expected to teach gender in my courses that survey the field. I avoid dwelling in this area because the discipline long ago aligned its subject matter with the demands of critical race and trans activists. I limit myself to discussing the origins of the patriarchy in the unit on historical materialism. I tell myself, and in terms of disciplinary siloing, this is perhaps reasonable, that gender identity disorder is properly the subject of clinical psychology. At the same time, psychology has also aligned its subject matter with the same ideological demands.

When an academic program or discipline becomes closely aligned with the moral or political interests of a specific group, dissenting views risk being framed not as alternative explanations but as betrayals or acts of hostility. I found this out firsthand despite skirting the issue in the classroom. My writing on this platform was enough to trigger complaints. I risk more of the same if my argument in this essay is perceived as a suggestion that programs like Women and Gender Studies should be abolished.

None of this implies that inequality or power should be excluded from academic study. On the contrary, these are central concerns in sociology and related fields. My course content is centrally focused on the problems of inequality and power, just as these matters are the focus of this platform. The question is whether the most intellectually robust way to study them is through programs that are explicitly organized as representational spaces for identity groups, or whether such organization inevitably constrains the range of permissible inquiry. A further problem is that, even with the proliferation of identitarian programming providing affirming and safe spaces for students, the policing of disciplinary and interdisciplinary curricula and teaching has generalized ideological and political constraints over higher education.

If universities are committed to the ideal of critical thinking, they must be willing to ask whether certain institutional forms, curricular programming, and pedagogical practices—however well-intentioned—unintentionally trade intellectual openness for moral and political solidarity. The challenge is not to abolish these programs (although I am increasingly persuaded that they might have to go or at least substantially reformed by forcing them open to intellectual diversity and protecting those who present alternative viewpoints), nor am I advocating for woke progressive teachers to be removed from their positions, but rather to confront honestly the structural pressures teachers face and the limits those pressures place on heterodox thought.

Without such reflection, the university risks confusing advocacy with scholarship and affirmation with understanding. Indeed, the fact that there are so few conservative students and teachers in the humanities and social sciences tells us that it already has. We cannot conduct science if explanations for behavioral, cognitive, and social phenomena are straitjacketed by movement ideology or protective empathy (see The Problem of Empathy and the Pathology of “Be Kind”). Colleges and universities (indeed, K-12) need to open curricula and programmatic spaces to other points of view and defend heterodox teachers and their materials against the manufactured orthodoxy that polices higher education to advance political objectives and movement goals. Liberal education is corrupted by ideological hegemony. It transforms the academic space into a system of indoctrination centers. It devolves the ideal speech situation into a succession of partisan struggle sessions. Those targeted for indoctrination check out. If that’s the purpose of such programming—to push conservatives out of the humanities and the social sciences—then the matter is settled: these programs must go.