The Trey Reed case came up in one of my classes. I was not familiar with all the details of the case, although I am the one who brought it up in response to a claim that lynching is still a problem. My point was not to interrogate the case but to note that authorities ruled the case a suicide and that, moreover, even if it were a racially-motivated killing (for which there is no evidence to my knowledge), it would not be a lynching for conceptual reasons. My point was to inject skepicism in the conversation. In this essay, I will explain my reasoning and provide details of the case after taking a closer look at the facts.

I begin with a disclaimer and a couple of statistical observations. This case is still ongoing, and evidence currently not publicly available may be forthcoming that indicates a racially-motivated killing. It would take additional evidence to conclude that it was a lynching. It should be noted that, although suicide among blacks is rarer than among whites, according to the CDC, for 2022 (the most recent year with a detailed demographic breakdown), of the 49,476 total suicides, 3,826 were blacks. Moreover, according to the FBI, for that year, there were 13,446 black homicide victims. Approximately 89 percent of those murders were perpetrated by blacks. Although most of those murders were perpetrated with guns, many other methods were also used to carry out homicide. Strangulation is not an uncommon method of murderers.

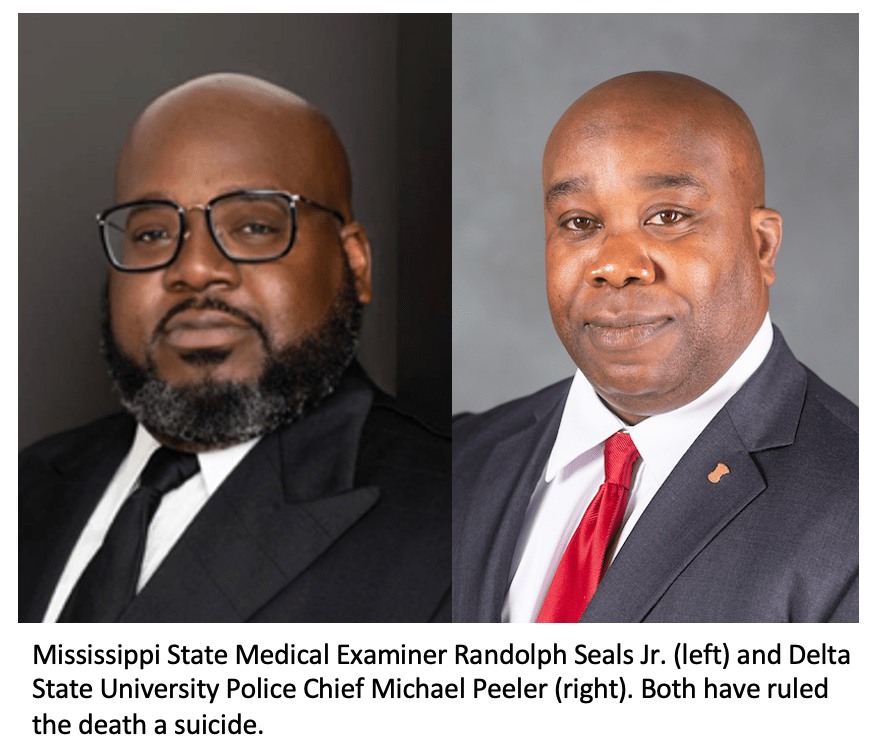

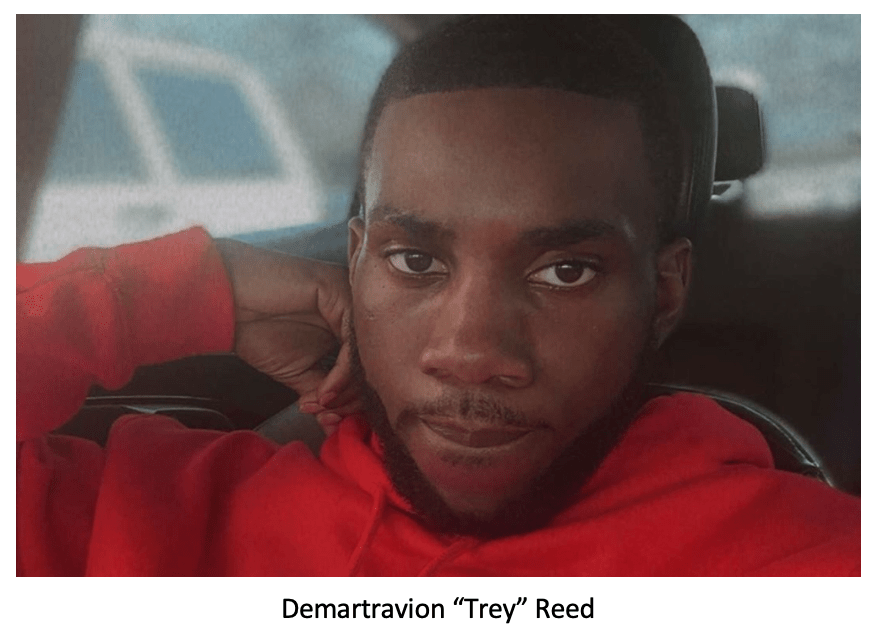

Demartravion “Trey” Reed was a 21-year-old Black student at Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi. On September 12, 2025, Reed was found hanging from a tree on the university campus. The Mississippi State Medical Examiner’s Office, led by Randolph “Rudy” Seals Jr., conducted an autopsy and ruled the death a suicide by hanging. Delta State University Police Chief Michael Peeler reported that the findings of his department were consistent with the local coroner’s conclusions, which noted no broken bones, contusions, lacerations, or other signs of assault. Peeler said there was no evidence of foul play. These facts were widely reported across the media.

Reed’s family was not satisfied with the ruling and has called for an independent autopsy as well as greater transparency, including access to video evidence. Civil rights attorney Ben Crump is representing the family in their independent investigation, and Colin Kaepernick’s “Know Your Rights Camp” is reportedly funding the independent autopsy. Additionally, US Representative Bennie Thompson has called for an FBI investigation.

The case has drawn comparisons to the history of racial violence in the United States, particularly lynching, which shapes how many people are interpreting the circumstances surrounding Reed’s death. Whatever the facts of the case, there is a conceptual problem with the claim of racial lynching in this case in that the historical and scholarly understanding of the phenomenon in the United States (Ida B. Wells, Stewart Tolnay and EM Beck, and many contemporary historians) emphasize that lynching was not merely a form of homicide but a public, ritualized performance of racial domination. (For my writings on the topic, see “Explanation and Responsibility: Agency and Motive in Lynching and Genocide,” published in 2004 in The Journal of Black Studies; “Race and Lethal Forms of Social Control: A Preliminary Investigation into Execution and Self-Help in the United States, 1930-1964,” published in 2006 in Crime, Law, & Social Change. See also Agency and Motive in Lynching and Genocide and There was No Lynching in America on September 24, 2024, on this platform.)

Racial lynchings were carried out by groups of white perpetrators against black victims, before large and small crowds, who treated the violence as a communal spectacle, for which they were held immune from legal consequences. This public and performative quality distinguishes lynching from private acts of violence or clandestine hate crimes; lynching’s purpose extended beyond harming an individual to terrorizing an entire racial community and reinforcing a social hierarchy grounded in white supremacy. I have described the phenomenon in my work as a public spectacle used to reclaim boundaries serving the interests of white racial exclusion and hierarchy. My thinking was inspired by James M. Inverarity’s “Populism and Lynching in Louisiana, 1889–1896: A Test of Erikson’s Theory of the Relationship Between Boundary Crises and Repressive Justice,” published in a 1976 issue of American Sociological Review. Inverarity’s analysis relies on Kai Erickson’s Durkheimian framework (boundary maintenance, deviance, and repressive justice) to test whether boundary crises in white political order produced repressive collective violence in the form of lynching.

By framing lynching as a subset of racially motivated homicide, especially as an act of boundary maintenance, this definition captures the essential features of audience presence, collective participation, and symbolic intent. It reflects the scholarly consensus that a lynching is best understood as a social ritual—an assertion of racial control—rather than simply as a killing motivated by racial animus. (My position was later supported in work by Mattias Smångs. See “Doing Violence, Making Race: Southern Lynching and White Racial Group Formation,” published in American Journal of Sociology in March 2016.)

There is no evidence that Reed’s death was a homicide or perpetrated collectively with audience presence. The surveillance video from Delta State University that might indicate this has not been publicly released because the investigation into Reed’s death is still ongoing. With no eyewitness reports of a lynching, video evidence would be necessary to make such a determination. Withholding video evidence by authorities is not uncommon. Authorities often withhold such footage to avoid compromising eyewitness interviews, forensic analysis, or potential criminal proceedings. Privacy concerns also play a role, as campus cameras frequently capture students and staff unrelated to the incident. Moreover, maintaining strict control over the chain of evidence ensures that the footage remains admissible in court, and early public release could raise questions about authenticity or tampering, as well as biasing the jury pool. However, if the video evidence did show such a thing, it is highly unlikely—so unlikely as to be implausible—that the public would not already know about it.

Without evidence, conceptual distinctions aside, how did the belief that this was a lynching emerge and spread? Misinformation about Reed’s death after the release of the initial autopsy. An individual operating an account claiming to be Reed’s cousin alleged that he had sustained injuries—specifically broken bones—that would have made suicide physically impossible. As noted, the initial autopsy does not indicate this. Although the creator of the misinformation later deleted the videos, as well as the account itself (I can find no information on the identity of the person behind the account), they went viral. Moreover, on a podcast, Krystal Muhammad, chair of the New Black Panther Party, claimed in a conversation with rapper Willie D that Reed’s mother had spoken to her about the contents of the second autopsy report. (I hasten to note that the original Black Panther Party has denounced the New Black Panther Party, emphasizing that it has no connection to the original organization.)

Terry Wilson, founder of the Idaho chapter of Black Lives Matter Grassroots, injected fuel into the moral panic, telling The Chicago Crusader ( “Lynching by Suicide: The Rebranded Face of America’s Racial Violence”) that the response from black Americans is deeply rooted in shared historical memory. “This sophisticated machinery of racial terror is just a fascist strategy that relies on overwhelming force from multiple directions, including misinformation, intimidation, and threats,” Wilson said. “I think we’re witnessing a coordinated campaign of disappearances, lynchings, and state-sanctioned killings that target Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities.” He added, “We need to address this method of ‘lynchings by suicide,’ which is their way of rationalizing, from a medical standpoint, their actions. I think this is sort of a death rattle for white supremacy, because they’re relying on nearly every structural institution to justify or cover up the actions of individuals.”

I trust the reader will recognize the hyperbole of these assertions. The apparent factual basis of the assertions was provided in part by a June 3, 225 Washington Post piece, “Lynchings in Mississippi Never Stopped,” penned by DeNeen L. Brown, a staff writer for the paper. Her claim that “[s]ince 2000, there have been at least eight suspected lynchings of Black men and teenagers in Mississippi, according to court records and police reports,” is valorized by the reputation of the Post as an objective mainstream news outlet.

However, every instance of death Brown cites was ruled a suicide by officials. One either accepts these rulings or supposes a conspiracy in which Mississippi state officials are covering up homicides. One must furthermore imagine that there was a racial motivation behind these homicides. Finally, if all these things could be proven beyond a reasonable doubt, one must alter the definition of lynching to classify these homicides as such. It should be kept in mind that around one-quarter of all suicides are the result of asphyxiation and that more than 90 percent of those involve hanging. That eight black men over 25 years chose hanging as a method of suicide is not an extraordinary fact.

According to The New York Times (“A Black Man’s Death in Mississippi Strikes the Nation’s Raw Nerves” ), Jy’Quon Wallace, the 20-year-old Delta State student who discovered Reed’s body, is sympathetic to Reed’s family but, in the absence of a second independent autopsy, is not inclined to automatically connect Mississippi’s historical racial context to the body he found. “A lot of people are trying to use this situation to make it seem like it’s racially motivated. There are a lot of signs pointing to this as not a racially motivated situation. When that whole story comes out, if it does come out, it may give some people clarity. It may not. That’s not up to us,” Wallace told the outlet.

In that story, The Times reports, “Mr. Reed’s death was twice ruled a suicide, and no evidence has emerged that would suggest otherwise.” However, even if Reed were the victim of homicide, it does not follow that the perpetrator(s) was/were white or that, if they were, racial animus motivated the murder. Evidence is needed to make these claims. Even if the second autopsy found that blunt force trauma to the back of the head was the cause of death, or at least part of the sequence of events that led to Reed being hung from a tree, thus indicating a murder, the substance of a common rumor, the more likely scenario is that somebody had a grievance against Reed and murdered him. Some would object with the quip that the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Sure, but when speculating, one has to consider relative likelihoods.

And that is what lies at the crux of this problem. Motivated reasoning makes up for the gap between the evidence and what many would like to believe—or have the others believe: that the United States remains a profoundly white supremacist nation where whites target blacks for violence. As I have shown on this platform, the reality is that whites are far more likely to be victimized (murder, robbery) by a black perpetrator than the other way around. This does not mean that racially-motivated violence does not occur (indeed, I would argue that the disproportionality just noted indicates its presence in contemporary society), but rather that, in the absence of facts indicating racism, it is a leap of faith fueled by ideology to believe without compelling evidence that white supremacy explains the Trey Reed case.

Note: The discussion of viral media claims was adapted from reporting by Daniel Johnson writing for Black Enterprise.