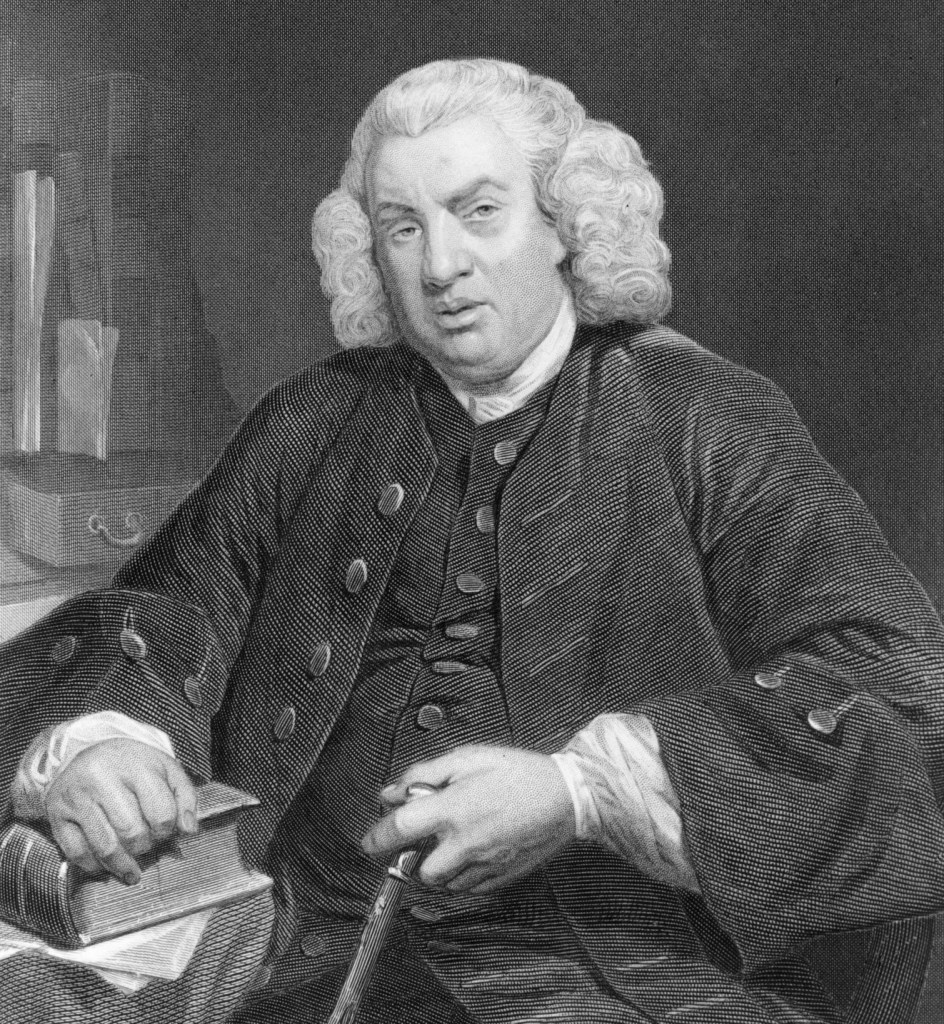

In one of his most memorable defenses of free speech Christopher Hitchens invokes a story about the great lexicographer Samuel Johnson to illustrate the hypocrisy and irony of censorship.

“When Dr. Samuel Johnson had finished his great lexicography, the first real English dictionary,” the late journalist tells his audience—prompting laughter—“he was visited by various delegations of people to congratulate him, including a delegation of London’s respectable womanhood who came to his parlor in Fleet Street and said, ‘Doctor, we congratulate you on your decision to exclude all indecent words from your dictionary.’ And he [Johnson] said, ‘Ladies, I congratulate you on your persistence in looking them up.’”

The anecdote, almost certainly apocryphal, has long circulated as a testament to Johnson’s wit and disdain for prudery. Hitchens took liberty with the legend. The most common historical version goes like this: a “proper lady” praised Johnson for omitting “indelicate” terms from his 1755 Dictionary of the English Language. Johnson, ever the master of pointed irony, is said to have replied, “What, madam! Then you have been looking for them?” I like Hitchens’s rendition better.

Whether or not the exchange truly occurred, it captures Johnson’s—and Hitchens’s—view that moral pretension often conceals the curiosity it claims to suppress. It’s like the smut police looking for smut to look at it. But there’s something darker here. Consider Elon Musk’s reminder that the social media platform X allows users to mute specific words and phrases so they don’t appear in their timelines or notifications.

I find it hard to imagine that many users would go to the trouble of identifying every word and phrase that offends them, and changing their settings to avoid ever suffering those ideas again. To do this, they would first have to use the very words they dislike—words they have already seen and thought about—in order to not see and risk thinking about them. That would hardly satisfy their impulse.

It’s not that they don’t want to see and think about the words and phrases per se. They think about them constantly. Like the proper lady who congratulated Dr. Johnson for excluding indecent words, the X user with this mentality doesn’t want others to see and think about them. He won’t go to the trouble of muting anything himself; he will instead complain that X fails to censor ideas he wishes others would not entertain.

He’s like those who want to restrict access to art and music. They know about the art and music they don’t want others to see and hear. If it were simply a matter of not personally looking at art or listening to music a man doesn’t like, the man would be content with looking or walking away, or turning down the volume, or changing the channel. No, the busybody’s aim is about something else: controlling what others see and hear. This is the mark of an authoritarian personality. And the busybody had an accomplice in Twitter’s previous owner.

When Twitter punished users for the thoughtcrime of “misgendering” (the act of correctly identifying the gender of a person), this was not merely to spare the man who thinks he’s a woman from having to be reminded of that fact—as if he enjoys in a free society the freedom to not be offended—but more importantly to change the way they talk and therefore think, by participating in the rituals demanded by gender identity doctrine, and disciplining them when they don’t. It was couched as “trust and safety,” but it was really about neurolinguistic programming.

Elon Musk saw through this impulse and gave the world a gift when he bought the platform and altered its algorithms to allow greater liberty in the exercise of free expression—to let people have their own minds, and thus the freedom to perceive and convey reality with accuracy and precision. That is the sign of a scientist and a civil libertarian. For this, America owes Musk a debt of gratitude.