“When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

These lines are from the Declaration of Independence, penned in the summer of 1776 to provide a clear rationale for breaking ties with Britain. More than this, the Declaration aimed to establish legitimacy for a new republic by grounding independence and the right to form a government in natural rights and the principle of popular sovereignty. It thus framed the United States as acting in accordance with universal principles of justice.

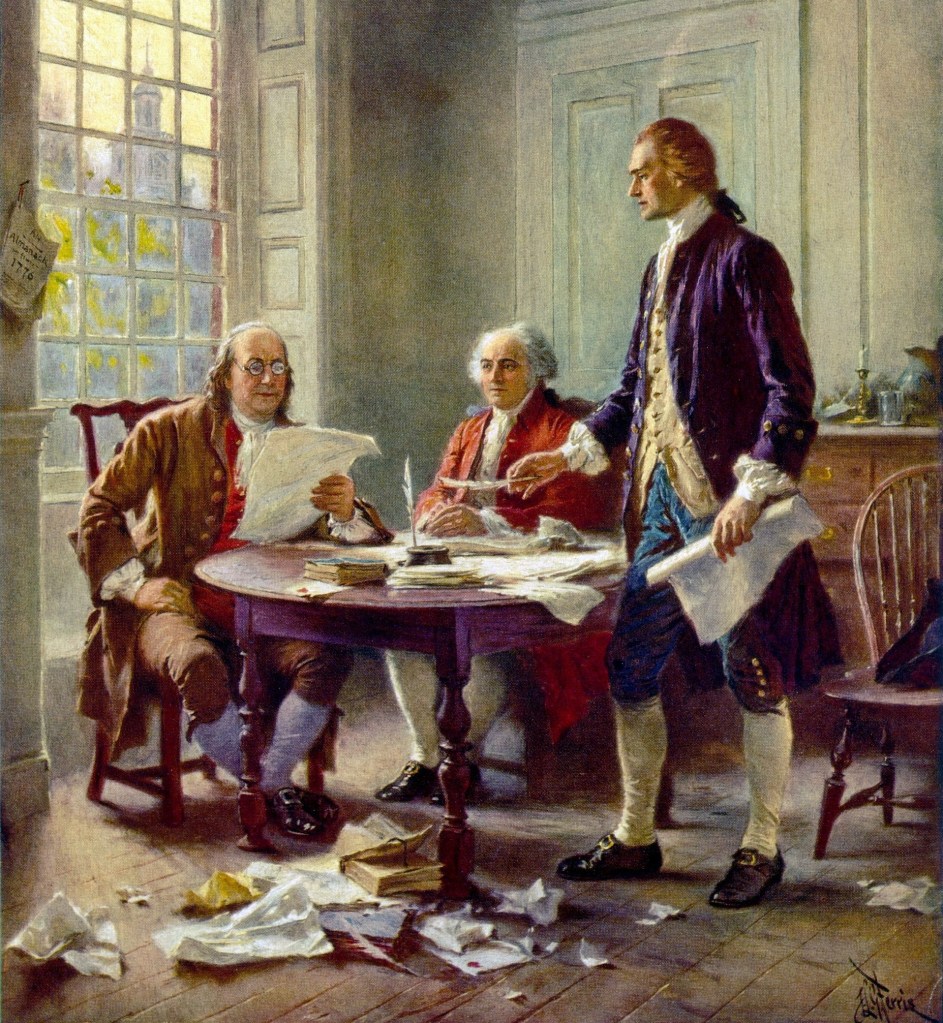

The Declaration was drafted primarily by one of the greatest Virginians, Thomas Jefferson, in June. He wrote it at the request of the Committee of Five—a group appointed by the Second Continental Congress—consisting of Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. Adams and Franklin made important edits, and the full Continental Congress debated and revised the draft before formally adopting it on July 4. Next summer, the American Republic will celebrate the 250th anniversary of its independence.

US Senator Tim Kaine, a Virginian and the man who was selected by Hillary Clinton as her potential Vice President, might want to revisit the Declaration of Independence.

Texas Senator Ted Cruz gave a compelling response, but his points require clarification. Who is the “Creator” Jefferson is writing about? Jefferson tells us in the text: “Nature’s God” who established the “Laws of Nature.” Kaine compares these ideas to Islam—but he is mistaken. Natural law is not a religious prescription; it is an observation—a self-evident truth.

The religious outlooks of the Committee of Five reflected the diversity of thought among the Founders (some were Christians, others were not), yet they converged on common ground in Enlightenment principles. Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin leaned toward deism, emphasizing natural law, reason, and the sovereignty of individual conscience. Livingston reflected the rationalist strain within the Reformed tradition. Among the five, only Sherman, a Calvinist, adhered to more orthodox Christian convictions.

Despite these differences, all agreed that human rights were not the gift of government but rooted in a higher order—whether understood through divine providence, natural law, or human nature itself. This convergence allowed them to craft the Declaration in language broad enough to resonate across faith traditions and philosophical outlooks, grounding the new republic in a shared commitment to liberty and the protection of individual rights.

Congress approved the Declaration without dissent on July 4. Every colony assented, making the vote unanimous. There were no imams, priests, or rabbis among the fifty-six delegates representing the thirteen colonies. However religious some of these men were, they did not impose religious authority on the American people. The Declaration they authored or assented to is unmistakably liberal and rationalist in character. It does not invoke revealed theology, denominational creeds, or sectarian authority. Instead, it grounds political legitimacy in natural rights, the equality of individuals, and the sovereignty of the people, all articulated in the language of Enlightenment philosophy.

The Declaration thus reflects a convergence: religious delegates could see in it the hand of providence, while deists and rationalists could recognize the operation of natural law. What united them was the conviction that rights are inherent, not granted by government, and that the purpose of republican government is to secure those rights against both majority tyranny and elite domination.

From this foundation, the Founders devised a Constitution and a Bill of Rights that embodied Enlightenment ideals in a system of government—a republic—grounded in popular sovereignty, where authority derives from the people and is exercised through a framework of representation and law. Unlike direct democracy, a system in which citizens make all lawmaking and policy decisions, republicanism channels popular will through elected representatives and constrains both rulers and the majority by constitutional principles and institutional checks. Its central purpose is to protect individual rights and the public good simultaneously, ensuring that government is neither arbitrary nor majoritarian, but rather manifests ordered liberty under the rule of law.

What is liberalism, then? One can infer its meaning from what has already been written, but its meaning should be made explicit: Liberalism is the doctrine that the individual is sovereign over his own associations, conscience, speech, and the fruits of his labor. It affirms that each person possesses an inviolable personal sphere—of expression, thought, and productive effort—the unalienable rights: “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”—that precedes and limits political authority over him.

The republican system is designed to protect this sovereignty, ensuring that no majority may vote away fundamental liberties and no minority of elites may rule over the people by fiat. Liberal principles provide the guardrails of republican government: they set the boundaries within which popular rule must operate, preserving ordered liberty by restraining both majoritarian excess and oligarchic ambition.

For republicanism to function, it must therefore be bounded by liberal guardrails—principles rooted in individual liberty, principles that issue from natural law, that is, human rights, which inhere in every citizen of a free republic. Ultimately, the individual is sovereign. His rights of conscience, expression, publication, and association are his own, free from government interference.

This moral framework acknowledges that human beings are social creatures whose sentiments often converge, and that democratic processes must exist to reflect shared sentiment. Yet even democracy is constrained by liberal principles. We do not live in a majoritarian system where the majority may vote away fundamental freedoms. Democracy requires dissenting voices—individuals and associations who challenge prevailing opinion—so that issues can be debated openly and consensus reached through rational deliberation. Rights do not—must not—come from government, but precede it, with government existing to reflect the will of the popular sovereign while protecting civil liberties and individual rights.

For republicanism to function, it therefore must be bounded by liberal guardrails—principles rooted in individual liberty—principles that issue from natural law, that is, human rights, which inhere in every citizen of a free republic. Ultimately, the individual is sovereign. His rights of conscience, expression, publishing, and speech to associate with those whom he wishes to, are his own, free from government interference.

This moral framework admits that human beings are social creatures whose sentiments often converge, and that democratic processes must exist to reflect that shared sentiment. Yet even democracy is constrained by liberal principles. We do not live in a majoritarian system where the majority may vote away fundamental freedoms. Democracy requires dissenting voices—individuals and associations who challenge prevailing opinion—so that issues can be debated openly and a consensus reached through rational deliberation. This is why man’s rights do not—must not—come from government, but precede government, with government existing to reflect the will of a popular sovereign—the people—while protecting the civil liberties and rights that are the birthright of every citizen.

The problem with progressivism—and why it is essential to emphasize that progressivism is not liberalism—is that the progressive mentality is technocratic in spirit. It seeks rule by bureaucrats and experts, subservient to elite power, treating both the individual and common sentiment as subordinate to elite knowledge. Liberal guardrails, while limiting democratic impulses by rooting sovereignty in the individual, also ensure that elites rule neither over the individual nor the populace without consent and within a rational, secular framework.

This is the essence of self-government. Progressives aim to transcend these limits, replacing self-government with rule by elites and their functionaries—the bureaucrat, the expert, the scientist. In a word, progressivism is technocratic: governance by unelected administrators, ultimately dictated by those who install themselves as overlords—the representatives of corporate class power.

This explains why Tim Kaine and his ilk argue that rights are granted by government rather than grounded in natural law. They want rights determined by the money-power that stands behind the politician, the corporatist ideology that moves the progressive policymaker, not by the self-evident nature of human beings. For, properly understood, natural law rests in human nature, which can be rationally examined and empirically observed. Since all humans share the same nature, the unalienable rights identified in the Declaration thus inhere equally in each person. No government can determine human nature. It must, in the final analysis, reflect it in establishing its foundational principles.

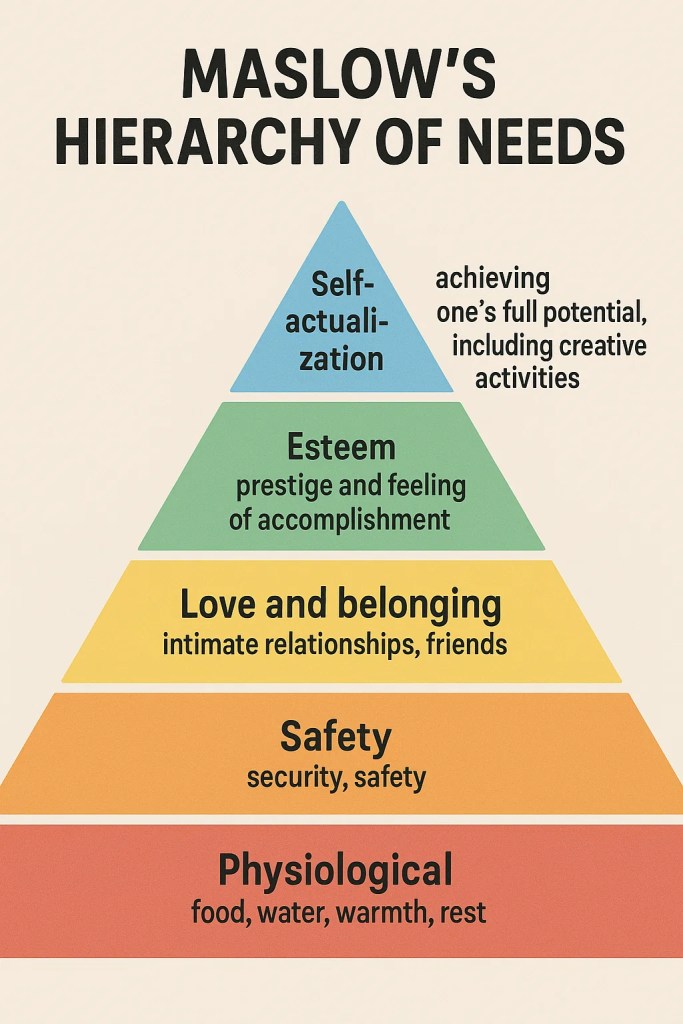

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs reflects this nature: meeting basic needs is essential not as an end in itself, but as a necessary condition for self-actualization—the full development of every human personality. Such development benefits all, not merely the majority, and certainly not a minority of the opulent. Maslow valued above all else human potential and personal freedom. His focus on individual growth aligns him with liberal, humanistic ideals rather than rigid ideologies. He criticized extreme collectivism for suppressing creativity, acknowledged the value of social support, and condemned authoritarianism, believing government should facilitate human growth, not control it.

Thus Maslow, like the Founders, centered human rights and rooted them in human nature. If a government can define our rights, then that government can also take them away—our freedoms of association, conscience, press, and speech. These freedoms are necessary conditions for citizens to deliberate together, envision their future, and work collectively toward it in ways that maximize the flourishing of individuals and society alike. A free society is not one in which all are identical, but one in which each individual has the opportunity to strive for self-actualization. Because we are social beings, our institutions must support that effort, but they cannot be structured to give one person an unnatural advantage over another.

Kaine’s argument is, at least superficially, majoritarian: if the majority elects representatives who legislate according to their views, then rights are defined by that process. There is no external source of liberty and rights. In practice, however, the interests served are not truly those of the majority. They are the interests of a minority of the opulent—the corporate elite who control cultural and economic institutions. Kaine is an animal of concentrated power, not a representative of individual freedom. Nor does he represent the popular will constrained by human rights.

In the republican system, liberal guardrails protect universal interests by safeguarding individual liberty and the pursuit of happiness from both the majority and the minority of the opulent. By contrast, Kaine’s approach places the definition of rights in the hands of elites claiming to represent the majority. In a late-capitalist order, where corporations wield immense economic power, this means rights will serve narrow interests rather than those of the people. Rights conceived of in this way are not properly rights at all, but the instruments of tyranny.

Kaine’s position thus reflects, at bottom, a totalitarian impulse. It must be rejected if we are to preserve a free society. Crucially, Kaine is not an outlier—he embodies the progressive ideology at the heart of the Democratic Party, which advances transnational corporate agendas. To reject his politics is to reject the politics of that party itself. Whatever one thinks of the Republican Party, whatever it was before its representatives were compelled to bend to the demands of the populists, today’s Republicans are the only political force representing the liberal foundations established by the Founders.

If Democrats prevail in the 2026 midterm elections, the nation risks losing the best opportunity it has had in decades to recommit itself to the ideals set forth in the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights—ideals reclaimed in the 1860s when the Democratic Party, the party of the Slavocracy, was defeated on the battlefield, but lost with the rise of progressivism. That would be a tragic way to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the greatest experiment in self-government since class power alienated humanity from its species-being so many millennia ago.