Last week, PBS published a story titled “Fact-checking Trump’s claims about homicides in DC.” I doubt PBS intended their report to come across this way—yet, in effect, they conceded the point. They acknowledged that Washington, D.C’s homicide rate is alarmingly high (even if reducing murders to near-zero would be difficult in a nation as large, diverse, and unruly as the United States).

“Washington, D.C’s homicide rate isn’t even the highest in the U.S.,” PBS tells its readers. “Per the February Rochester Institute of Technology report, the district has the fourth highest homicide rate in the U.S. after St. Louis, New Orleans and Detroit.”

Fourth? Our nation’s capital ranks behind only St. Louis, New Orleans, and Detroit. DC is worse than Baltimore? Chicago? Kansas City? Memphis? The seat of the federal government sits among the top four most violent cities in America—an outlier even by First World standards, with crime levels more commonly associated with the developing world.

This hardly undercuts Trump’s case for making DC safer. If anything, it underscores the urgency.

Corporate media outlets, echoing progressive academics and politicians, consistently stress that crime rates nationwide are declining. They cite recent FBI statistics and local police reports showing drops in certain categories—property crimes or homicides in select cities—as evidence that public fears of rising lawlessness are overstated or politically motivated.

The message is clear: America is safer than in previous decades, and concerns about crime spikes are either temporary fluctuations or distortions amplified by conservative media.

Against this backdrop, Donald Trump’s push to reintroduce a hardline “law and order” agenda—expanding police powers and imposing tougher sentencing policies—is portrayed not only as unnecessary but also as dangerous. Critics argue his rhetoric stokes fear, reinforces racialized narratives of urban disorder, and reflects an authoritarian impulse: prioritizing control and security over addressing social drivers of crime, such as inequality, housing shortages, or mental health challenges. (At least, that is the progressive framing.)

But the premise is flawed. Crime did not fall under the Biden administration. At best, it stabilized after sharp pandemic-era increases, with stabilization occurring only toward the end of his term. Yet a plateau offers cold comfort to ordinary Americans still facing daily risks of victimization. A neighborhood plagued by break-ins, shootings, and theft is no safer simply because the crime rate stops rising.

The public knows this instinctively. Citizens witness armed robberies on security cameras, shoplifting in broad daylight, smashed car windows, and neighbors or coworkers becoming victims. They do not need sanitized headlines to judge their own safety. They need effective public safety measures—and many recognize they cannot rely on Democrats to deliver them.

The progressive insistence that crime is “down” amounts to lying by omission: cherry-picking statistics, dismissing victims’ lived experiences, and ignoring persistent, real-world danger.

I will focus here on the cherry-picking. The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), which collects data directly from households, shows that a large share of crimes never appear in police reports. Between 2020 and 2023, only about 38 percent of violent victimizations in urban areas were reported to police—lower than in suburban (43%) or rural (51%) areas. With at best half of all crimes reported, media and expert claims about falling crime deserve extreme skepticism.

Systematic underreporting means official sources, like the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report (UCR) program or the Crime Data Explorer (CDE), present a highly incomplete picture. When Americans hear that crime is “falling,” they are hearing only about reported incidents—not the full scope of lawlessness.

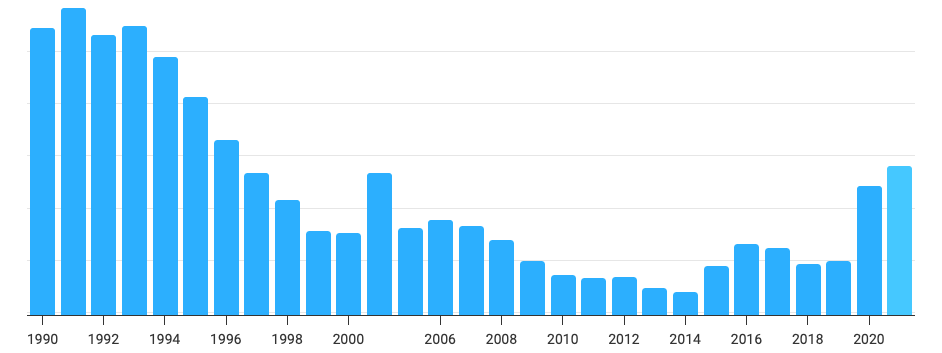

Historically, NCVS and UCR trends moved roughly in parallel: crime peaked in the early 1990s and then declined, with NCVS estimates typically 2–3 times higher than UCR counts. However, between 2020 and 2023, NCVS data show a notable increase in serious violent crime, while FBI-reported crime decreased. The divergence suggests a shift in reporting or recording practices rather than a true decline in criminal activity.

However, between 2020 and 2023, serious violent crime as measured by NCVS increased notably. During that same window, FBI-reported violent crimes decreased. Thus, while NCVS suggests a significant rise in victimizations, particularly those not captured in police data, UCR indicates a decline in reported violent crime—highlighting a widening gap, in this case diverging in opposite directions. This tells us that something has changed in the way the FBI measures crime.

While UCR data may show, for example, a certain number of aggravated assaults in a given year, the NCVS consistently finds that far more such assaults occur but are never reported to law enforcement. This means that the apparent decline in some categories of crime may not necessarily be the result of fewer assaults, but rather the result of fewer victims reporting incidents, whether due to cynicism, fear, or frustration with a justice system they no longer trust.

The gap between official statistics and victim experiences represents a serious flaw in the narrative being advanced by progressive commentators and politicians.

Victims avoid reporting for many reasons. Some distrust law enforcement, influenced by years of rhetoric depicting police as corrupt or racist. Others fear retaliation in neighborhoods where enforcement is lax. Some citizens, even when reporting, experience inaction: police may decline to investigate property crimes, prosecutors may drop charges, and officers may be discouraged from proactive policing to avoid political backlash. Residents of crime-ridden neighborhoods recognize these dynamics.

Underreporting by victims is compounded by the reality that agencies from our most crime-ridden neighborhoods, i.e., the Blue City (urban areas run by Democrats), withhold data from the federal government because these data make their cities look bad. This is not speculation. The FBI’s UCR makes clear which agencies report, and the politicization of data is undeniable.

The incentives are obvious: reporting crime exposes high-crime areas, and because black Americans are overrepresented in crime statistics, it also raises uncomfortable racial questions. Public narratives that criminal justice disparities reflect systemic racism have influenced perceptions, but many Americans—what some call experiencing “black fatigue”—recognize that crime remains disproportionately committed by young black males, even if the majority of black Americans are law-abiding.

Reflecting on the discrepancies, I stress this paradox to my criminal justice students: rising arrests or reports can indicate better policing, while falling crime in UCR may not mean fewer crimes—but simply fewer reports or fewer arrests. Effective crime reduction requires both active policing and citizen engagement. Put another way, solving the problem of crime in America (as in any society) takes a whole-of-society approach.

Persistent crime is not solely a policing issue. When offenders are apprehended but prosecutors fail to pursue charges, or judges release criminals quickly, public safety is further degraded. More police—and, if necessary, the military—can deter crime, but prevention requires aggressive prosecution and incarceration. Those taken off the streets must remain off the streets to achieve real impact. Offenders cannot victimize others if they are in prison.

Deterrence and incapacitation were the primary drivers of the dramatic drop in crime from its historic highs in the 1980s and 1990s: more police on the streets, aggressive law enforcement, harsher penalties, and the expanded use of prisons.

Progressives have long criticized the large US prison population, yet they resist social policies that could alter the dynamics in our most crime-ridden neighborhoods. And this isn’t about taking guns off the street (more on that shortly). The issues are deeper: broken families, a subculture of idleness and violence, and conditions stemming from deindustrialization, ghettoization, mass immigration, and the rise of the welfare state.

The progressive abandonment of law and order policies set against the backdrop of idleness and welfare dependency, further complicated by anti-police and prison abolitionist rhetoric from the progressive left, is what led to the return of significant crime and violence after 2014. Whether one relies on the NCVS or the UCR, the return of serious crime is not in dispute.

Who suffers the most because of all this? Black Americans. Blacks are far more likely to be the victims of crime and violence perpetrated by other blacks in the neighborhoods into which urban elites have directed and in which they have trapped them over the decades.

The failure to protect blacks in crime-ridden communities is a phenomenon Randall Kennedy calls “racially selective underprotection.” Indeed. It puts the lie to the “Black Lives Matter” slogan. It also prompts a rational person to ask: Who are the real racists here?

Now, about guns. This is an important piece in all this since politicians and progressives say the problem of crime (homicide, robbery) can be dealt with by diminishing the public’s access to firearms, a right protected by the Second Amendment. It’s part of the argument PBS makes in the story that inspires this essay.

I must note that, paradoxically, taking guns off the street would require a vast expansion of the law enforcement apparatus, given the number of guns in America and the reluctance of citizens to give up their most effective means of self-defense. Indeed, more strident gun control would lead to more crime, not less.

John R. Lott Jr. (More Guns, Less Crime) makes a compelling argument that legally owned firearms—carried by law-abiding citizens—serve as a powerful deterrent to crime. Criminals prefer unarmed and vulnerable targets, so when potential victims are armed, the risks of committing violent crimes increase, leading to fewer such offenses.

According to Lott’s careful analyses, states that adopt “shall-issue” laws making it easier for citizens to carry concealed weapons generally experience less violent crime. While some criminals may shift toward lower-risk property crimes, the overall effect of legal gun ownership is to reduce victimization.

Gun control thus disarms law-abiding individuals rather than criminals, thereby undermining public safety. In this case, what feels intuitively true is empirically sound.

I used to be on the other side of the gun argument (see The Truth About the AR-15 and The Sandy Hook Shootings: What Really Happened). My error was due to a category error. A gun cannot be guilty of murder. Yet progressives treat guns as if they have agency. But guns don’t shoot themselves; people shoot guns. People have agency. (I apologize for my error here: Guns Don’t Shoot Themselves.)

But supposing that guns themselves are a problem, is it true that more guns mean more violence? Let’s look at the facts.

From the 1960s through the 1970s, US gun ownership rose to roughly 40,000–60,000 firearms per 100,000 people as production increased, with gun homicides peaking around 7 per 100,000 in 1974.

In the 1980s, ownership climbed to an estimated 60,000–80,000 per 100,000, while the overall homicide rate averaged about 8.7 per 100,000, plateauing or gradually declining by the decade’s end.

We are approaching the peak of violent crime in American history in the 1980s, driven by demographics (more young men in the population) and the fruit of progressive policy hollowing out America’s industrial base and destroying the black family. Gun proliferation is not driving the crime problem. Indeed, it is likely a response to the experience of rising crime.

While the 1990s saw ownership reach about 74,000 per 100,000 (192 million guns for a population of ~260 million), the average homicide rate declined to around 8.1 per 100,000. Gun homicides had peaked in the early 1990s (the absolute zenith of criminal violence in America) before falling nearly 49 percentage points by 2010, even as ownership continued to grow.

This sharp decline was not thanks to the so-called assault weapons ban (1994-2004). As I have explained before on this platform, rifles account for a small proportion of guns used in homicide. More people are killed with feet and hands than are killed with rifles. Most gun deaths are perpetrated with handguns (more than half).

In the 2000s, the gun stock likely reached 90,000–110,000 per 100,000 people, while the homicide rate averaged 5.6 per 100,000, with overall gun deaths declining (with suicides making up the largest share).

By the 2010s, ownership had stabilized between 110,000–120,000 per 100,000 (roughly 40–45 percent of households owning guns), and the homicide rate averaged 4.9 per 100,000, continuing the long-term downward trend.

If guns explain homicides, then more guns should be associated with more homicides. But gun ownership has increased over the last several decades, while the homicide rate decreased during the same period. Thus, it would seem that the causal relation is the inverse of what PBS’s expert claims: more guns means fewer homicides.

What explains this? The likelihood that an armed citizen is a deterrent to those who wish to inflict harm on him explains a lot of it. But it’s also because a more expansive criminal justice system saves lives, since police presence deters violence and incarceration keeps violent offenders away from the general public.

If America locked up 2.3 million people and didn’t reduce crime, then one would have reason to doubt the efficacy of incarceration. But the reality is that homicide was reduced because of deterrence and incapacitation effects. So were car thefts, etc. Law and order work. Progressive approaches to crime and disorder don’t. Indeed, they make the situation worse (for obvious reasons).

Remember, during the BLM craze, when the police were told to stand down, and the prison population declined, thus allowing more violent offenders to operate more freely on our streets? What happened? What any rational person would expect: Homicides increased. Car theft increased. Etcetra. As Lott likes to say, this isn’t rocket science.

One other thing, and this is crucial for understanding the false claims gun grabbers make. Approximately 46–47 percent of American adults who report owning a gun live in rural areas, which have much lower rates of homicide than urban areas. Suburban areas? About 28–30 percent of adults say they personally own a gun. Again, not areas with a lot of homicides.

But Urban areas? Roughly 19–20 percent of adults report owning a firearm, yet many inner-city neighborhoods are killing fields, including DC. Why? Not because of the amount of guns, but because the people there are much more likely to murder people.

Democrats don’t want Trump to stop the killing. Weird, right? And conservatives and their guns are somehow to blame for crime. More weirdness.

To put the matter bluntly, crime reporting in the mainstream media is garbage. It’s a pack of lies promulgated by those who are simultaneously striving to make guns the problem, while excusing the consequences of progressive social policy—not only in the area of criminal justice, but in the areas of economic policy and the welfare state.

It’s time to get back to what works: law and order. Public safety is a human right. Liberty lives where people are safe to go about their business and their lives.