I couldn’t disagree more with Josh Bell’s complaint in his review of the new FX/Hulu series conceived by director and writer Noah Hawley: “The Alien franchise hits a wall with TV series Alien: Earth,” published in Inlander. It’s not that I have no criticisms of the series—I do, although I won’t consider them here, since I am still progressing through the series—but I reject the idea that the franchise is venturing into territory it shouldn’t. In fact, it’s going exactly where I hoped it would go from the start.

I was seventeen when Alien premiered in May 1979. I found a seat up front in the Martin Twin Theater (in Jackson Heights Plaza, Murfreesboro, Tennessee), ready for whatever Ridley Scott had in store for me. The TV campaign had given us almost nothing—just enough eerie imagery and sounds to make it irresistible. With no Internet to offer clues or ruin the shock, we went in blind, unprepared for the horror of the chestburster scene. I shrank in my seat the way others in the theater must have. I didn’t scream. But others did.

Scott’s Alien tells the story of a deep-space mining expedition whose course is secretly altered—known only to the synthetic Ash, his identity also concealed from the crew—to collect an alien species for the Weyland-Yutani Corporation, one of five conglomerates that dominate Earth in a transnational corporatist order. This voracious system seeks the spoils of interstellar space, including other life forms. In this future, the world’s proletariat—and the synthetics embedded among them—serve the interests of technological overlords. The parallel to our own emerging reality is unmistakable. As he would do in 1982 with Blade Runner, Scott gave us a window into a possible future with Alien.

Corporate intrigue has never been an incidental subplot to Alien; it’s embedded in the series from the start. Scott’s fascination with world-building ensures that, just as the xenomorph has an origin story (collected or created by the Engineers), so does Ash. Alien has the structure of a slasher film. I love the action and horror of the genre as much as anyone. But what really fascinates me about Alien is the deeper horror: the realization that humans—and other humanoids across the stars—are consumed by an obsession with biotechnology and the Promethean desire to transcend the forms provided by natural history.

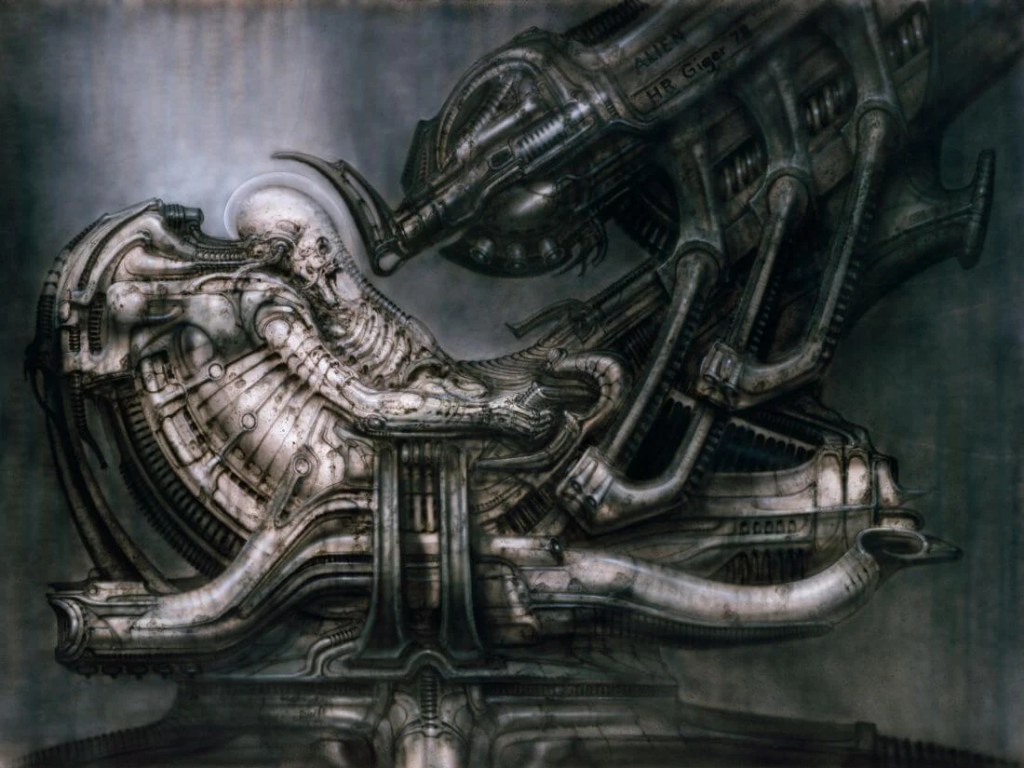

That’s why, when I saw Alien on opening night, the moment that haunted me most wasn’t the chestburster scene—it was the fossilized Engineer seated at that vast HR Giger contraption aboard the derelict ship. The archaeologist in me burned to know the story behind it. I had to wait until 2012, with the release of Scott’s Prometheus, a flawed but compelling prequel, to get answers.

Prometheus takes place 27 years before Alien: Earth. The follow-up Covenant (2017) occurs a decade after Prometheus. Alien: Earth is set two years before the events of the original Alien, set in the year 2122. Thus, Hawley’s story partly fills the gap between Covenant and Alien that a future theatrical release promised. (Will we ever learn the fates of Daniels, David, and the USCSS Covenant and its cargo?)

It’s in Prometheus and Covenant that we learn how the Weyland Corporation first encounters alien life. CEO Peter Weyland (a fictional character anticipating the ambitions of Elon Musk, as I note in a recent essay, From Neon Rain to Corporate Space: Blending the Histories of Alien and Blade Runner) may have been more interested in the Engineers and immortality, but the acquisition of alien species became central to Weyland-Yutani’s ambitions (the corporate merger of Weyland and Yutani occurring in the aftermath of the events of Covenant).

In Alien: Earth, the USCSS Maginot, carrying alien life forms, crashes into Prodigy City, New Siam, in futuristic Thailand. Because of what happens there, Weyland-Yutani knows it must keep the crew of the USCSS Nostromo (the ship in Alien) ignorant of the Maginot’s fate—and the catastrophic consequences of the company’s ambitions. Thus, when the Nostromo, returning from Thedus, picks up the distress signal from LV-426, the crew knows nothing of the fate that awaits them. In the depths of interstellar space, they have no knowledge of the hybrids realized by wunderkind Boy Kavalier. The plot of the original Alien thus remains untouched—a self-contained story of corporate exploitation. The difference is that we, the audience, now know the context. Far from spoiling the original, the FX series, and Prometheus and Covenant before it, enrich it. This is the beauty of an expanded universe—provided it doesn’t distort the core backstory.

Critics who fault Hawley for introducing existential themes into the franchise overlook that Scott himself already did, exploring them in the prequels. Scott introduces these themes through the exploration of humanity’s hubristic desire to transcend natural limits, a premise embedded in Alien itself, which we learn from Mother, the AI that runs the Nostromo (a shoutout to Kubrick and Clarke’s Hal 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey). We also learn in the original film about the intrinsic pathological potential of synthetics, which mirrors the amorality of the xenomorph (recall Ash’s admiration of the creature).

In Scott’s 2012 prequel, the crew of the USCSS Prometheus embarks on a quest to find the Engineers, the mysterious species Weyland believes to have created humanity. They travel to LV-223, a distant moon orbiting a gas giant in the Zeta 2 Reticuli system (see my June 2012 essay Ridley Scott’s Prometheus and the Problem of Time Dilation for more). LV-223 is near LV-426 (aka Acheron), the planetoid in the original Alien. The search raises fundamental questions about human origins and the nature of our creators, forcing the characters—and the audience—to confront whether life itself has inherent meaning or whether our makers are fallible and even malevolent. Weyland’s obsessive pursuit of immortality highlights humanity’s desire to cheat death and assert control over existence, raising questions about the cost of such ambitions and the hubris inherent in attempting to transcend natural limits.

Another existential theme is the tension between humans and their creations. David, a synthetic, exhibits curiosity, creativity, and, at times, malice, blurring the boundary between creator and creation. The synthetics turn not only on the human crews in which they are embedded, but also turn on their creators (a theme also explored in Blade Runner). Through David, Scott challenges assumptions about what it means to be human and probes the ethical implications of playing god—and the inevitable boomerang of having done so.

At the core of his concerns, Scott emphasizes the fragility and expendability of human life in the corporate gaze. Both films place characters in the presence of cosmic forces—the Engineers, xenomorphs, alien landscapes—that dwarf them, underscoring their vulnerability and the existential uncertainty of their—indeed our—place in the universe. The unleashing of the xenomorphs and the chaos that ensues serve to illustrate this key existential idea: our creations escape our control and even turn against us, reflecting on the unpredictability of life and the limits of human knowledge. The Gods punished the Titan Prometheus for giving man the technology of fire. Like Dr. Frankenstein, man punishes himself.

In these ways, Scott uses the prequels to explore profound existential questions about origins, creation, ambition, and mortality. These themes set the stage for Alien: Earth, where Hawley continues to probe humanity’s obsession with biotech, the consequences of overreach, and our fragile place in a vast, indifferent universe. Bell’s review of the FX series moves from a superficial understanding of Scott’s vision. This suggests that he has not spent much time with the Alien franchise—or dwelled much in Scott’s other dystopian world, the world of the blade runner.

All that said, if I were introducing a novice to the Alien franchise, I’d start with the original film. Not only would this preserve the shock of the chestburster scene, but more importantly, mirror how we come to understand any world—ours included. We don’t receive a neatly packaged explanation before we experience what life throws at us. We live it first and afterward ask, “What the hell just happened?” Taken chronologically, the Alien franchise unfolds like a murder mystery or the excavation of an ancient site. Along the way, we deepen our understanding of humanity and the terrible potential that lies at the heart of corporate ambition. Hawley’s Alien: Earth (with Scott serving as executive producer) continues our journey of discovery. For that reason, whatever its flaws, the new FX series works.