Since we’re reflecting on the problem of kings (and on July 4 we will celebrate America’s declaration of independence from the British Crown), it seems an apt time for a brief civics lesson on the distinctions between democracy, liberalism, monarchism, and republicanism.

A liberal democracy features the following: constitutional limits on government power, free and fair elections, pluralism, tolerance of dissent, protection of civil liberties and political rights, the rule of law, and separation of powers.

The United States is certainly these things in design. While we have faced challenges—fraying separation of powers (the rise of the judicocracy), strained tolerance for dissent (the Biden regime directing social media to censor and deplatform those who views challenge the official narrative), threats to electoral integrity (the 2020 election)—the institutional framework remains intact. What is required now is the political will to make these institutions function as they were intended.

The United States was founded on classical liberal principles: consent of the governed, free markets, individual liberty, limited government, natural rights (life, liberty, property), rule of law, and secularism. When I say I am a liberal, I mean that I subscribe to these things. My only qualification concerns the notion of free markets, particularly the tension between nationalism and globalism, as I have discussed many times before on this platform.

When one says that the United States is a liberal democracy, he is often confronted with this rebuttal: “We are not a democracy. We are a republic!” Yes, we are also a republic. However, putting it this way obscures the fact that we are also a liberal democracy. These two terms are not mutually exclusive.

A democracy is a system of government in which ultimate power resides with the people. In its purest form—direct democracy—citizens vote directly on laws and policies. James Madison was wary of direct democracy, fearing the “tyranny of the majority,” in which the rights of individuals and minorities are endangered by the will of the majority. In Federalist No. 10, Madison argued that the best safeguard against this danger was his blueprint for a constitutional republic. Thus, we are a representative democracy—like most modern democracies—where the people elect officials to make decisions on their behalf.

The core idea of the republic is a system of government in which there is no monarch. When I say that I am a republican, this is what I mean: no kings. However, while all true republics are a form of representative democracy, not all democracies are republics (nor are all states without a monarchy republics). Many modern constitutional monarchies—such as the United Kingdom, Sweden, Japan—are liberal democracies, with robust institutions and free elections, yet they still retain ceremonial monarchs. They are not republics.

Conversely, some countries that call themselves republics, like China, are anything but democratic. The Chinese Communist Party controls all branches of government, the military, and the media, with no checks and balances, free elections, or genuine political pluralism. Crucially, then, “republic” is a structural description—it is a design for government—not a guarantee of democracy or liberalism.

The United States is both a democracy and a republic: democratic because power derives from the people; republican because it is governed by elected representatives under a constitution that limits government power.

Last Saturday, progressives have made it clear that they don’t want a king. Great. Neither do I. So what do progressives want? They reject the American system, so we know they don’t want that. Instead, they advocate for an administrative and technocratic model—a system in which policy is shaped not by elected representatives responsive to voters, but by a class of bureaucrats and experts managing complex systems with minimal democratic input. This is what we call corporatism.

Corporatism is prevalent in much of Europe, particularly in parliamentary systems based on proportional representation. Corporatist systems integrate organized interest groups—businesses, labor unions, professional associations—into formal policymaking processes. In this system, politics is less about competition among ideas and more about cooperation among elites, with the government acting as a coordinator among powerful groups.

One feature of this system is agency independence, in which unelected bureaucrats manage the lives of the populace according to administrative plans. Agency independence reflects a technocratic approach to governance, where unelected bureaucrats wield significant authority over public policy and everyday life. This independence is intended to insulate decision-making from partisan pressures, allowing experts to manage complex social and economic issues through long-term planning and coordination.

Here’s the problem: this arrangement distances governance from democratic accountability, as policies emerge from negotiated compromises among elite interest groups rather than electoral mandates or public debate. The result is a political environment where citizens are alienated from policymaking, as crucial decisions are made by insulated agencies whose legitimacy derives more from expertise than from popular consent.

Thus, while corporatism offers efficiency (at least ideally) and stability, it does so by reducing the influence of ordinary citizens. A corporatist society behaves more like a corporate bureaucracy where decisions are made through closed-door negotiations among shareholders (excluding stakeholders), and where the machinery determining policy is opaque. The priorities of organized interests take precedence over grassroots demands, and the public becomes more of a managed audience than an active participant. Legitimacy in such a system stems not from popular will but from the perceived competence of institutions—leaving little room for dissenting voices outside the sanctioned channels of influence.

By formalizing elite control over policymaking, the state system marginalizes the broader electorate. It does this on purpose. Elite cooptation undermines democratic accountability and dilutes the principle of popular sovereignty. When interest groups act as gatekeepers to power, they prioritize narrow agendas over the common good, excluding diverse perspectives and suppressing dissent. This is why populism is universally reviled by elites and technocrats. In an act of projection, elites have taken to equating populism—another word for popular democracy—to fascism. You see this inversion across the West.

Why do I say projection? Because corporatism has an ambiguous character in the sense that it can operate within democratic institutions, but also slide into authoritarianism. Twentieth-century fascist regimes came to power through parliamentary systems and adopted corporatist structures to control civil society and eliminate democratic opposition. This dual nature highlights corporatism’s vulnerability to authoritarianism: it weakens the checks that liberal republicanism provides—civic participation, individual rights, separated powers—thus creating fertile ground for elite domination.

When progressives accuse populists of fascism they are projecting, accusing those who seek open democratic processes governed by republican principles and liberal values of the very thing progressives seek: an authoritarian corporate state.

The genius of the United States is that its governmental structure makes the installation of an authoritarian regime difficult. However, the rise of the unaccountable, unconstitutional, and unelected fourth branch of government—the administrative state—can, and to a significant degree has established what Sheldon Wolin called “inverted totalitarianism.”

In Democracy, Inc., Wolin argues that the United States has evolved into a system of managed democracy where corporate power dominates political life without the overt repression typical of classical totalitarian regimes. Unlike traditional authoritarianism, inverted totalitarianism maintains the façade of democratic institutions—constitutional rights, elections, a free press—while hollowing them out through consumerism and technocratic control. Wolin contends that this system suppresses genuine democratic engagement by depoliticizing the public, prioritizing market efficiency and stability over accountability and civic participation, effectively rendering democracy a symbolic ritual rather than a substantive practice.

The rise of the administrative state has fueled the growth of populism, as many American patriots seek to reclaim the republic in the spirit envisioned by the Founders. In the absence of a single authoritarian figure, the public has struggled to recognize the nature of their predicament—particularly given the legacy media’s dominance over public perception.

By casting a strong presidential figure leading a populist movement as an authoritarian, the cultural and institutional establishment has convinced many Americans that Trump poses a threat to democracy. When branding him a fascist failed to resonate, elites pivoted to portraying him as a king. Yet, just a week after the “No Kings” protest, that narrative appears to have fallen flat. Trump remains a highly popular figure, consistently polling above 50 percent in the most reliable surveys. But the corporate elite and their functionaries and street-level troops do not intend to give up.

Understanding the distinctions between corporatism, democracy, liberalism, monarchism, and republicanism is not an abstract exercise—it is essential for defending the American System. The United States was founded not on bloodlines or bureaucracies, but on the belief that individuals possess inalienable rights and that government derives its just powers from the consent of the governed. In contrast to corporatist models that favor elite cooptation and technocratic control, the American system rests on the conviction that ordinary citizens—through debate, democratic participation, and dissent—shape their political destiny.

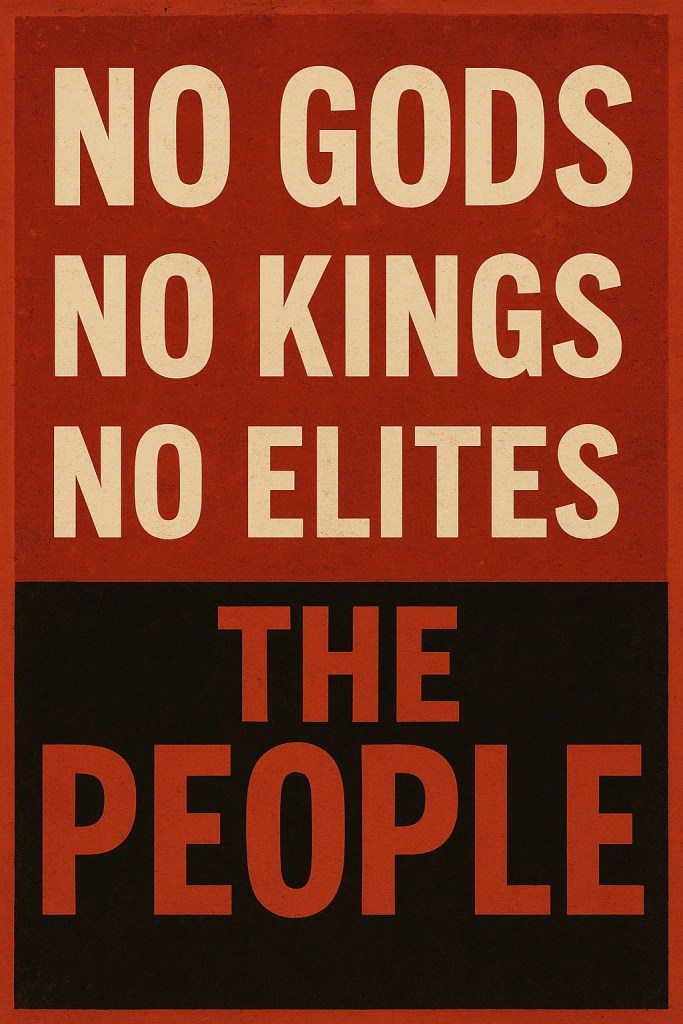

To preserve this republic, we must not only understand the meaning of terms but recommit ourselves to republican principles of liberalism, secularism, and the rule of law. No gods. No kings. No elites. The People.