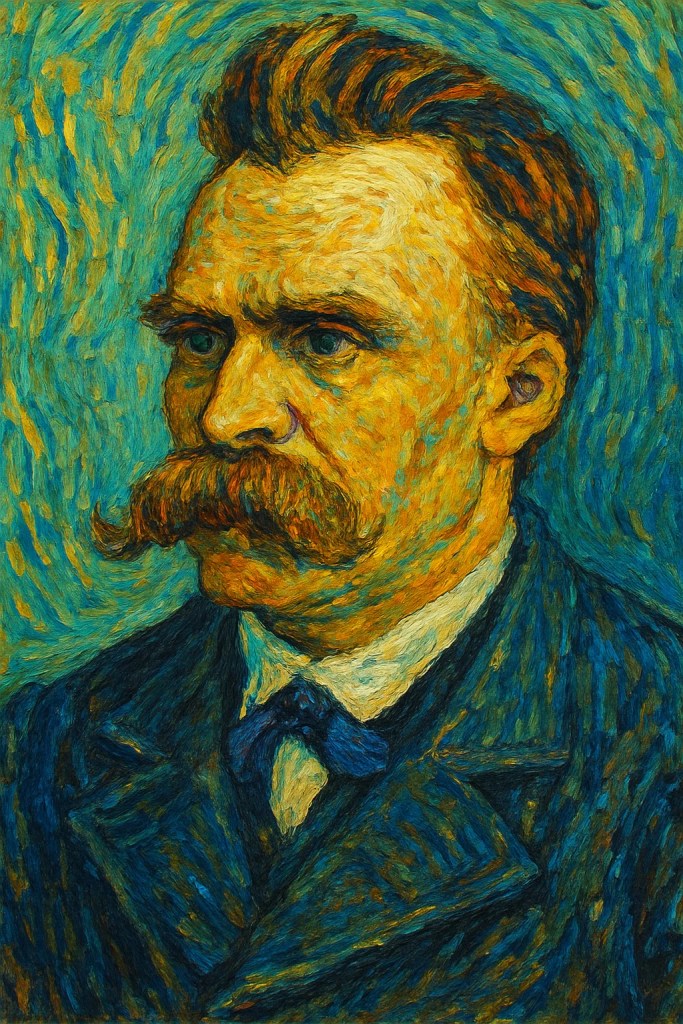

In the context of my lectures in Freedom and Social Control (also in Social Theory) on Paul Ricoeur’s thesis of the “masters of suspicion,” Friedrich Nietzsche occupies a central position alongside Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. Each of these thinkers, according to Ricoeur, embodies a hermeneutics of suspicion—a method of interpretation aimed not at understanding surface meanings, but at exposing the hidden power structures and desires that lie beneath. Nietzsche, in this triad (an unholy trinity, if you will), is the one who most rigorously dismantles the moral and metaphysical scaffolding of Christianity and its cultural inheritance in the West.

Yet Nietzsche’s influence does not end in the realm of philosophy or theology. His radical revaluation of values also helped shape the methodological and cultural sensibilities of modern sociology—most notably in the work of Max Weber. Weber’s concept of the “disenchantment of the world” and his ambivalence toward rationalization reflect a world profoundly shaped by Nietzschean suspicion, especially toward inherited metaphysical meaning. In what follows, I present Nietzsche’s critique of Christianity and then return to how his influence echoes in Weber’s sociological imagination.

At the heart of Nietzsche’s critique is his distinction between “master morality” and “slave morality.” Master morality, rooted in antiquity, emerges from the affirmation of life and power. It values beauty, power, and self-assertion. Slave morality, on the other hand, is born from weakness and ressentiment—a vengeful revaluation of values by those without power (suggestive of Friedrich Engels’s conceptualization of demoralization in The Condition of the Working Class in England, used to describe the profound moral and psychological degradation experienced by the working class under industrial capitalism). According to Nietzsche, Christianity institutionalized slave morality, portraying humility, meekness, and suffering not as necessary evils, but as moral ideals.

In On the Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche traces how the early Christians, oppressed by Roman rule, reshaped morality to favor their condition. In doing so, they turned traditional values upside down. What had once been seen as noble and life-affirming—ambition, pride, strength—were rebranded as sinful, while weakness and submission were reimagined as virtues. In The Gay Science and Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche’s infamous proclamation—“God is dead”—strikes at the heart of Western metaphysics. This declaration is not atheistic triumphalism but a cultural diagnosis. Nietzsche recognized that modern secular societies continue to rely on the moral assumptions of Christianity even after losing faith in its theological foundations.

By saying that we have killed God, Nietzsche implicates modern humanity in the collapse of the metaphysical order. He warns of an impending nihilism—the absence of meaning, purpose, and objective value. This moment of crisis, however, is not the end but a challenge: can humanity create new values in the aftermath? Nietzsche believed this task required the rise of the Übermensch, one who can live creatively and affirmatively without recourse to transcendent absolutes.

For Nietzsche, Christianity was more than mistaken—it was anti-life. He argued that its teachings encourage a rejection of the body, instinct, and earthly joy in favor of spiritual purity and a promised afterlife. Likewise, Antonio Gramsci in his Prison Notebooks employs the term “animality,” particularly in the section titled “Americanism and Fordism,” to capture the historical struggle to suppress the “element of ‘animality’ in man,” referring to the natural, instinctual behaviors that industrial capitalism seeks to discipline and regulate.

Gramsci explicitly links the concept of animality to Puritanism, which functions as a cultural and moral framework used to discipline the working class in capitalist societies—particularly in the United States—by repressing the instinctual, spontaneous, and sensual aspects of human life. He observes that in the development of American industrial capitalism, especially under Taylorism and Fordism, there was a concerted effort not only to rationalize labor processes but also to morally reform the worker by cultivating habits of punctuality, sobriety, sexual restraint, and self-control. These values, deeply rooted in Puritan religious and cultural traditions, were repurposed by industrialists and reformers to create a more disciplined and efficient labor force.

Gramsci argues that this attempt to eliminate animality is not simply technical but cultural and ethical, aimed at creating a new type of human being suitable for modern industrial production. Ford’s program of moral surveillance—offering bonuses to workers who adopted “respectable” domestic lifestyles—exemplified this intervention. Gramsci interprets these measures as secularized Puritanism: a disciplinary apparatus designed to align workers’ private lives with the demands of capitalist production. Thus, he sees Puritanism as a historical and ideological tool in the struggle to suppress the natural, “animal” aspects of human life that could disrupt the rationalized order of capitalism. This repression, for Gramsci, is not simply about productivity but about constructing a hegemonic moral order that naturalizes capitalist social relations.

In The Antichrist, Nietzsche writes with unmistakable vitriol: “Christianity is a rebellion against natural instincts, a protest against nature. Taken to its logical extreme, Christianity would mean the systematic cultivation of human failure.” In Nietzsche’s view, Christian morality cultivates guilt and shame—particularly through its doctrine of original sin. Instead of empowering individuals to affirm their instincts and embrace life in all its complexity, Christianity demands submission and self-denial. This makes it, in Nietzsche’s words, a “will to nothingness.”

Despite his disdain for Christianity as a doctrine, Nietzsche admired Jesus as a figure who embodied love and inner peace without dogma or resentment. In The Antichrist, Nietzsche claims that Jesus lived and preached an aesthetic, not a moral life—a life of radical inner transformation that was later distorted by Paul and the Church into a system of judgment, doctrine, and power. “The very word ‘Christianity’ is a misunderstanding—at bottom there was only one Christian, and he died on the cross.” This distinction underscores Nietzsche’s central concern: that the Church preserved not the life-affirming example of Jesus, but a perverse moralism that turned life itself into something to be ashamed of.

Nietzsche’s critique of Christianity and his broader cultural diagnosis had a profound influence on Max Weber (and probably through Weber, on Gramsci), though Weber rarely acknowledged it directly. Both thinkers grappled with the consequences of secularization, but where Nietzsche feared the rise of nihilism, Weber analyzed its social forms—especially the bureaucratic rationalization of modern life. Weber’s concept of the “disenchantment of the world” (Entzauberung) echoes Nietzsche’s death of God. In a world increasingly dominated by scientific reason, bureaucratic efficiency, and instrumental logic, traditional sources of meaning—religion, myth, and metaphysics—lose their authority.

While Nietzsche calls for a new kind of individual to create meaning, Weber remains more ambivalent: he sees modernity as at once liberating and constraining. For Weber, the Protestant ethic—shaped by Calvinist Christianity—ironically laid the groundwork for modern capitalism and rational bureaucracy. This irony resonates with Nietzsche’s suspicion: values born in a religious, ascetic context end up fueling a secular, impersonal economic order. The “spirit” of asceticism survives, but stripped of its religious framework—a process Nietzsche would recognize as another transformation of values through history and ressentiment.

Nietzsche also stands in a tense and revealing relation to his fellow “masters of suspicion,” Freud and Marx. Like Nietzsche, Freud understood religion as a psychological projection, an illusion born of human weakness. In The Future of an Illusion, Freud describes religious belief as a collective neurosis—a system of wish-fulfillment designed to shield humanity from the harshness of reality. Nietzsche anticipates this view but goes further: rather than merely reducing religion to illusion, he exposes the value system behind it as a historically contingent moral framework rooted in weakness and ressentiment.

Before both of them, Marx framed religion as ideology and a painkiller—“the opiate of the people”—but also as a symptom of material alienation. In the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Marx famously describes religion as “the heart of a heartless world,” not merely false consciousness but a protest against real suffering. Nietzsche shared Marx’s insight that religion is historically embedded and socially functional, yet where Marx seeks emancipation through collective material transformation, Nietzsche seeks liberation through individual revaluation.

Each of these figures, in his own way, demands that we see religion not as divine truth but as human product—deeply implicated in structures of desire, power, and social organization. By placing Nietzsche in dialogue with Paul Ricoeur’s “masters of suspicion” thesis and Max Weber’s sociology, we begin to see the depth and range of his influence. Nietzsche does not merely critique Christianity; he inaugurates a deeper suspicion toward all inherited systems of meaning. His work represents both a demolition and a provocation—an insistence that values are not given but made, and that their history is often one of conflict, inversion, and power.

In Max Weber, we see the sociological legacy of this suspicion. While Nietzsche tears down the metaphysical edifice, Weber examines what arises in its place: a world where reason reigns but purpose fades, where institutions thrive but meaning dissolves. And in Freud and Marx, we find parallel expressions of Nietzsche’s impulse—one psychological, the other materialistic—each dismantling the illusions that uphold inherited and illegitimate authority. Together, they form a constellation of modern critique, united by a determination to uncover what lies beneath appearances and to demand a reckoning with the true sources of belief and value.

Nietzsche’s challenge endures: if the old gods are dead, and their shadows still haunt our morals and institutions, what shall we build in their place? His answer is not a system, but a call—to courage, to creativity, and to a life lived without illusion.

Before leaving this essay, I must record a note about Weber’s influence on Gramsci, which I earlier suggested. I believe my assumption that Weber influenced Gramsci is largely accurate, albeit with nuance. Gramsci does not appear to be directly influenced by Weber in a systematic way in the sense that he did not engage Weber’s work extensively or explicitly (not in anything I have read). However, there are converging concerns: both thinkers grapple with rationalization, the moral consequences of modernity, and the role of culture and ideology in social control. I have always been struck by the similarity between Weber and Gramsci’s critique of industrialism, both finding Americanism the paradigm of bureaucratic rationality. I must conclude, then, that, indirectly, through debates circulating in early twentieth century European Marxism, especially through interlocutors like Georg Lukács, Weber’s influence percolated into broader intellectual currents that shaped Gramsci’s thinking.

For certain, the Frankfurt School—especially thinkers like Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and later Jürgen Habermas—more deliberately synthesized Marx, Freud, and Weber. They credited Weber with illuminating the cultural and institutional dimensions of capitalist modernity that Marx had only partially addressed. Gramsci, although often treated as a precursor or cousin to Critical Theory, maintained an independent trajectory rooted more in Marx, Machiavelli, and Italian political thought. Still, my framing is justifiable in a pedagogical context that highlights how these traditions intersect—and how Nietzsche casts a long shadow across all of them.

Perhaps one day I will produce a podcast in which I capture the essence of my lectures on the masters of suspicion in my courses Freedom and Social Control and Social Theory. If that never happens, readers of Freedom and Reason will have this essay to know what I talk about in those courses. Some will reasonably ask what, if anything, college students gets out of such esoteric matters. I make two assumptions about that. First, I never presume that students are incapable of grasping the more high-minded ideas in social theory and moral philosophy. I do not see them as Hobbits (nor do I see Hobbits the way elites see the ordinary man). And, secondly, as one of my professors in graduate school once remarked to me, “Never hesitate to expand your students’ vocabulary.”