One frequently encountered argument regarding race is that race is a social construct—that it has no inherent biological basis but is instead rooted in superficial phenotypic characteristics and the stereotypes derived from them. According to this view, the social roles historically assigned to different races are arbitrary and constructed rather than essential or natural. I have long taught this point of view in my sociology courses. It was what I was taught as a student. One finds this point of view across the anthropological and sociological literature.

A parallel argument is often made about gender: that gender, too, is a social construct without essential biological grounding. Like race, it is said to be based on socially imposed stereotypes tied to outward appearance or behavior. The roles historically assigned to men and women are, in this view, culturally constructed and socially imposed rather than biologically determined. These roles are learned and internalized through socialization, including anticipatory socialization.

Yet when it comes to how society reacts to individuals crossing these constructed boundaries, we see a striking inconsistency. When a white man adopts stereotypically black dress, speech, or mannerisms—engaging in what is often termed a performance of blackness—he is accused of “blackface” and branded a bigot. His actions are condemned as offensive, and those who speak out against them are seen as standing up for racial justice. The underlying assumption here is that the white man is appropriating something that does not belong to him, something intrinsic to black identity.

However, if a man adopts stereotypically feminine dress, speech, or mannerisms—engaging in a performance of womanhood—he is not typically accused of “woman-face” or labeled a bigot. Instead, criticism of his performance is often branded as transphobia, and the man is affirmed in his self-identification. In this context, gender is treated as fluid, performative, and open to personal redefinition. Critics of this treatment of gender and personal identification are bigots.

What explains this double standard? Why is it that race, which is claimed to be a social construct, is treated as essential and exclusive, while gender, also claimed to be a social construct, is treated as flexible and inclusive?

The implication is that, despite rhetoric, society essentializes race. A black person is seen as essentially black, such that even a performative act by a non-black person is deemed a violation. This is not true in the inverse. Consider that in recent years, film and theater have increasingly embraced diverse casting, including black actors portraying roles originally written as or traditionally played by white characters—even when those characters are historical figures. This trend is celebrated as a form of artistic reimagining and social progress, aiming to correct longstanding disparities in representation. Casting choices like these are defended as empowering and inclusive, especially given that white actors have historically dominated the stage and screen, often to the exclusion of non-white performers.

The reverse—casting a white actor to play a black historical figure—would likely provoke widespread condemnation. This reaction is rooted in the history of blackface and racial caricature, which makes such portrayals deeply offensive regardless of artistic intent. Critics point to the asymmetry of power: while marginalized groups taking on roles of privilege can challenge dominant narratives, dominant groups portraying the historically marginalized can come across as appropriation or erasure. While this may seem like a double standard, it is justified by the historical and systemic context in which these portrayals occur. The prevailing consensus is that representation cannot be separated from the realities of history and power.

By contrast, gender is not treated in the same way; it is considered open to performance and self-definition in both directions. Men can be women. Women can be men. Thus, while both race and gender are often described as social constructs, the social and moral frameworks surrounding them diverge. In the case of race, society tends to treat the identity as fixed and inviolable—except where in performance where blacks are empowered to assume white roles. In the case of gender, society increasingly embraces the idea that identity is fluid and performative altogether.

We are taught that the “black role”—the cultural identity and expression of blackness—is the result of historical oppression. It emerged within the context of slavery, segregation, and systemic racism, and therefore occupies a space of resistance and survival within a dominant framework of white supremacy. Consequently, when a white man adopts the black role—by imitating black vernacular, dress, or artistic expression—he is seen as trivializing this struggle. His performance is interpreted not as homage but as mockery, a form of exploitation that reasserts racial hierarchy. He is accused of appropriating cultural expressions born of pain and resilience for his own benefit, gaining social currency while bypassing the lived experience of black oppression. Moreover, such appropriation grants him access to spaces—linguistic, social, or symbolic—that have traditionally been carved out for black people as sanctuaries or affirmations of identity.

But if this logic holds for race, why does it not apply to gender? Is the woman role not also the result of historical oppression? Has it not, too, developed under centuries of subjugation—patriarchy, legal exclusion, domestic relegation, and gender-based violence? Just as blackness is shaped by its historical position relative to white dominance, femininity has been shaped by its historical position relative to male dominance. So why is a man’s adoption of the woman role—through dress, speech, or mannerisms—not interpreted as a similar kind of appropriation?

Does it not, in parallel, allow the man to access spaces traditionally reserved for women, including shelters, support groups, athletic competitions, and intimate conversations shaped by shared experience? Does it not enable him to use the language developed within feminist and female-centric contexts—the female experience, menstrual health, or women’s empowerment—without having lived the realities they emerged from? If a white man performing blackness is accused of reinforcing racial superiority under the guise of identification, could a man performing womanhood not be seen, by the same logic, as reinforcing male privilege—using the social authority he retains as a man to redefine what it means to be a woman?

A common defense of the man who adopts the woman role is that he does not merely perform femininity externally but experiences a deeply felt internal sense of being a woman. This sense of identity is described as essential, even if it is subjective and unverifiable. Whether labeled “gender dysphoria” or “gender identity disorder,” it has been medicalized and, in many frameworks, essentialized: the body is said to be misaligned with the true self, and thus medical intervention is appropriate—indeed, necessary—to bring external appearance into alignment with internal identity. Hormones, surgeries, social accommodations—these become pieces of affirming care, steps toward congruence and psychological well-being.

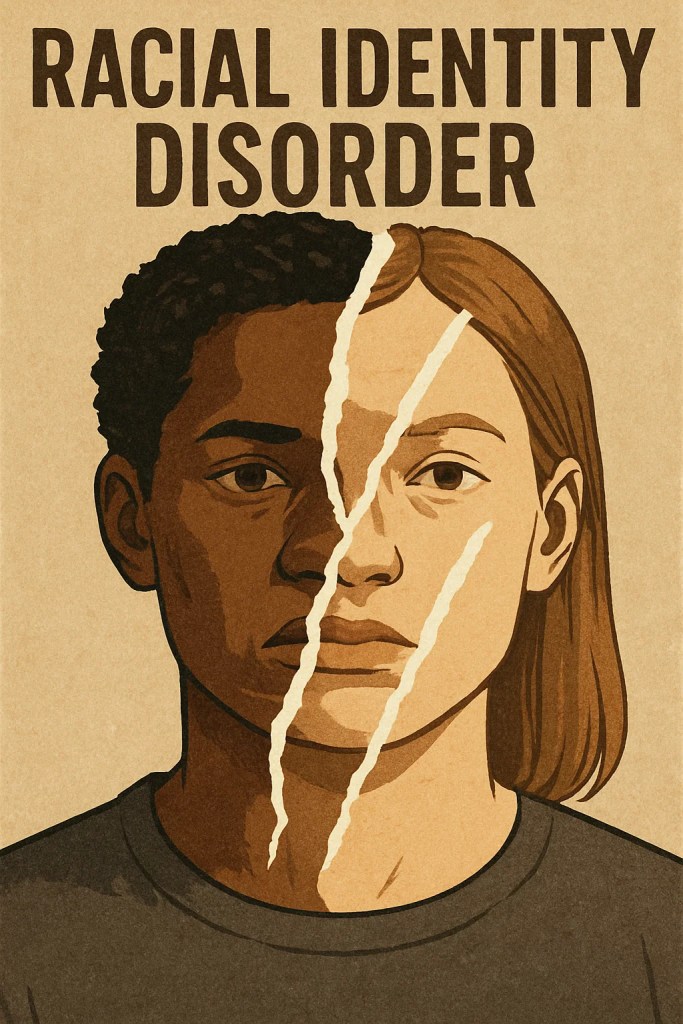

But why does this line of reasoning not apply to race? Why is there no serious public argument for the concept of a white man who believes or feels that his identity is, internally and essentially, that of a black man? You may object that this is not a widespread phenomenon, but neither was gender identity until only a little while ago in historical terms. There are people who identify as the other race. Why are they not affirmed in their identity? Why not speak of “racial identity disorder” or “race dysphoria”? If one can claim that their inner sense of gender overrides the physical and historical realities of biological sex, then why can’t the same be said for race?

A person who identifies as black, despite being born white, might seek medical and social interventions to bring his appearance and experience into alignment with his internal identity. This could include skin darkening treatments, changes in hair texture, or speech coaching—what we might call “racial affirming care.” Even without medical procedures, such a person might present himself as black, participate in black spaces, and expect recognition of his racial identity based on personal experience and conviction. Would he be entitled to this by today’s lights? Could he be a diversity hire at the institution or organization?

No. Society overwhelmingly rejects this. Such a person is typically ridiculed, ostracized, and accused of deceit and appropriation. Their internal identity is not affirmed but denied, even condemned, regardless of the depth or sincerity of their experience. The case of Rachel Dolezal, for example, was not treated as a matter of racial dysphoria but racial fraud. The very suggestion that one could “feel black” or possess a black identity absent black ancestry is seen as offensive—a form of theft, not self-expression. But what does it mean to “feel female”? Would you not have to be one?

This again reveals the asymmetry. While gender identity is treated as subjective, psychological, and potentially in conflict with biology or social history, racial identity is treated as fixed, external, and rooted in inherited experience. Gender, we are told, lives in the mind; race, it seems, lives in the blood. Thus, despite claims that both are social constructs, society treats gender as interior and malleable, and race as exterior and immutable.

This development is striking consider the biological foundation—or lack thereof—of the categories in question. As noted at the start, the claim that race is not essential, that it is constructed from superficial phenotypic traits such as skin color, facial features, and hair texture, is widely accepted in the social sciences and for much of biology and physical anthropology. While these traits correlate to geographic ancestry, they do not meaningfully divide humanity into discrete biological races. Instead, these visible traits have been socially organized into categories—“black,” “white,” “Asian,” etc.—which are then imbued with roles, expectations, and stereotypes. In this view, race is imposed from the outside in.

Gender, however, rests on a more robust biological foundation. It is tethered to a host of deeper biological realities: chromosomal configurations (XX vs. XY), gametes (ova vs. sperm), internal and external reproductive anatomy, and secondary sex characteristics. These distinctions exist independent of social categorization and are relevant not only to reproduction but to a wide array of physiological and developmental processes. The essentialist view of sex is not a matter of superficial traits, but of fundamental biological organization.

Paradoxically, though, it is gender that is now treated as mutable, fluid, and internally defined, while race—which rests on far thinner biological ground—is treated as fixed and sacred. This reversal leads to an irony: from a purely biological standpoint, a white man performing the black role and claiming black identity may actually be less of a stretch than a man claiming to be a woman. The white man’s “whiteness” is not encoded in a unique chromosome or gamete; it is a loose proxy for ancestry and phenotype. By contrast, the man’s male body is rooted in a suite of anatomical and genetic realities that cannot be changed in kind, only in appearance.

Moreover, when viewed through a historical lens, the subordination of women by men predates the transatlantic slave trade or European colonization by millennia. Patriarchy is not merely a social system—it is, in many cultures, a civilizational bedrock, deeply interwoven with religion, law, family structure, and language. If one argues that it is offensive for a white man to appropriate black identity because it trivializes centuries of black struggle under white domination, then, by the same logic, one might argue that a man adopting womanhood trivializes thousands of years of female subjugation under male dominance.

In this light, society’s current framework—affirming gender identity while rejecting racial identity—begins to look not only inconsistent but internally contradictory. The man who claims womanhood is asking society to affirm an identity in spite of biology and history. The white man who claims blackness is denied for precisely those same reasons. The standard, then, is not principled but cultural—one built on shifting political sentiments rather than coherent logic.

This asymmetry becomes even more pronounced when we consider those who reject the binary system altogether. In the context of gender, there is growing recognition of individuals who identify as nonbinary—those who do not see themselves as either male or female, or who claim a fluid identity that transcends traditional categories. While sex remains biologically binary, gender is treated as a spectrum, or even as optional. A person can be affirmed not only in transitioning from one role to another, but in refusing to perform any gendered role at all.

But where is the analogous concept in race? Why is there no mainstream recognition of a person who is nonracial—someone who does not identify with any racial group and refuses to perform race altogether? In a society that claims race is a social construct without essential biological grounding, this should be entirely possible. If race is externally imposed and historically constructed, then surely one should be permitted to disavow it, to decline participation in racial identity just as one can decline participation in gender roles.

Yet in practice, society offers no space for racial nonconformity. A person who claims to be “raceless” (spellcheckers don’t recognize the word) is often met with confusion, suspicion, or accusations of privilege and denial. To refuse race is to refuse the terms by which power, identity, and belonging are currently organized. Even in contexts that celebrate nonbinary gender identities, racial identity remains strictly policed. One must belong to some race, even if that race is “mixed” or “other.” Racial categories are treated as compulsory and immutable, despite their acknowledged artificiality.

This raises a final and uncomfortable contradiction: gender, which is grounded in biology, can be dismissed, redefined, or transcended. Race, which is acknowledged to be a social fiction, must be performed, claimed, or affirmed. One cannot opt out of race, even though race has no essential reality. But one can opt out of gender, despite sex being among the most deeply rooted biological features of the human body. The conceptual framework that permits nonbinary gender identities but forbids nonracial ones reflects not a coherent theory of identity, but the selective application of social norms.

In the end, the double standard is not merely an inconsistency within our cultural logic—it is an inversion of biological reality. A society without racial roles and identities is imaginable, perhaps even desirable, if one accepts the premise that race is socially constructed and not biologically essential. Indeed, the human species can thrive without maintaining rigid racial categories. Nothing about reproduction, survival, or social cooperation depends on treating race as real.

But a society without gender—or more precisely, without sex distinctions—is not imaginable in the same way. Human beings are a sexually dimorphic species. The terms “man” and “woman” are not arbitrary labels but describe biological roles in reproduction. While gender is often treated as distinct from sex, in reality the two are inseparable: even if they are not treated as synonyms, gender is the cultural expression of sexual dimorphism. To argue otherwise is to deny that the categories “male” and “female” correspond to any objective natural facts. The perpetuation of the species depends on the existence—and recognition—of those very facts.

A white man and a black woman can produce children. A man and another man cannot. A black woman and an Asian man can form a family in the biological sense. A woman and a trans woman cannot. However much one may wish to reconstruct identity through culture, medicine, or language, sex remains stubbornly real, and its implications universal. It is embedded not only in human history, but in the evolutionary logic of life itself.

Therefore, if we follow the logic of biology rather than ideology, and if we are to find any of this controversial, it is not transracialism that ought to be controversial, but transgenderism. Race is contingent and context-bound; sex is cross-cultural, transhistorical, and essential to life. The irony is unmistakable: the very identity we treat as fluid and performative—gender—is the one rooted in biology, while the one we treat as immutable—race—is arguably nothing more than skin deep. We have built a cultural orthodoxy on a foundation precisely opposite the facts it claims to defend. Gender ideology is a nonsensical position, which would be fine (there are lots of nonsensical position) but for the harm it causes in practice and its acceptance by governments and the organization that shape our lives.