My college at my university just released the results of a survey of my college concerning AI use. I missed the administration of this survey, so my opinions are not reflected in the report. Wednesday, I published a timely essay on acceptable AI use, On the Ethics of AI Use. I didn’t share it on social media on Wednesday because I didn’t want to step on my more pressing essay on the Signal chat story (The Set Up: Déjà vu All Over Again).

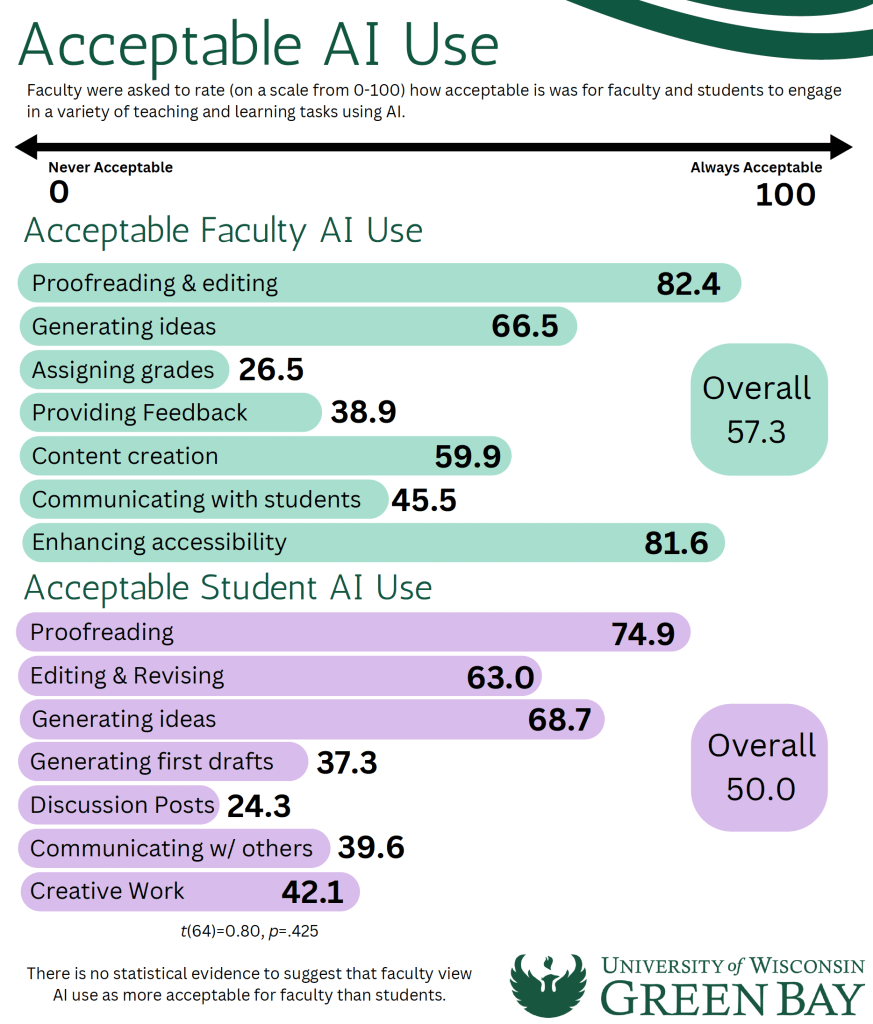

I took a screen shot of the relevant page of the Taskforce finding and share it here (see above). I am heartened to see that a large majority of the faculty of my college who responded to the survey finds acceptable use of AI in proofreading and editing, both for faculty and for students. ChatGPT is a solid copyeditor (so is Grammarly, especially in its enhanced features). I am also pleased to see that faculty recognize the importance of AI in the use of generating ideas (a sizable minority finding it acceptable for creative work, as well).

I am a dismayed about the number of faculty who find AI useful for content creation (a large majority, actually) and a sizable minority that find it acceptable for students to use AI for first draft generation. On the latter matter, there is a difference between using AI to generate ideas and generating first drafts. If generating first drafts follow from an outline where sources have been used (and these are appropriately found using AI as a research assistance), this is arguably more acceptable, but I am concerned that some students will prompt AI to generate first drafts. Students could do this to generate a template to understand what an academic essay looks like, as AI systems model good form and writing mechanics (and writing tutors are practically unavailable), but drafts should be in a student’s words.

How one would know whether the student generated a first draft using AI, given that drafts written on a computer are polished over time, would require surveillance, such as saving drafts to present to their teachers, which is inappropriate—it’s just the way most people work these day. So it becomes a trust issue (a problem in October 2023 addressed by philosopher Daniel Dennett, summarized in this interview). We mustn’t let AI create a climate of suspicion that negative impacts academia. To be sure, the trust issue is already upon us, and this is conveyed elsewhere in the survey, but we must resist this temptation.

I hasten to identify a problem in this regard, which I note in Wednesday’s essay on the ethical use of AI. When proofreading and editing documents using AI, which, again, is acceptable, it raises the likelihood that the paper will be flagged as AI generated (e.g., by GPTZero). This is what’s called a “false positive” and, while initiating a disciplinary process based on these results is wrong, I fear some faculty will do just this. Why it’s wrong is that AI detection is flawed technology. Not just for identifying human-generated text as AI generated, but also because of the problem of the “false negative.”

I recently asked ChatGPT to rewrite Karl Marx’s preface to his essay “A Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Right” in the style of Christopher Hitchens. I then entered the output unaltered into GPTZero. It reported that the content was 100 percent human generated. It was in fact 100 percent AI generated. Students will learn this trick soon, as such things are quickly socialized, and simply ask the bot to rewrite their paper in the style of a human author and easily evade detection. So why would we attempt to prosecute cases of academic dishonesty using these systems? Suspicious faculty could wreck a student’s academic career using flawed technology. Use of AI detection should be disallowed for this reason, and universities across the country are disallowing it on these grounds. (I have an essay on this coming soon.)

I have been warning my students this week about the risk of using AI in copyediting in their other classes. I allow it in mine because it improved their work and enhances their understanding of science writing. But I tell them that my rules are not transferable to other courses. I tell them to speak with their professors and clarify the matter.

One of the complaints about AI-assisted work is that it compromises creativity and originality. This argument may sound familiar to some of old timers. Academics were skeptical of calculators in the 1970s when this technology rolled out. But calculators testify to the importance of technology in advancing knowledge and productivity. Now calculators are standard in math and science classes. The same is true with statistical packages, etc.

This applies to the arts, as well. It goes for old technology, too. When I was in high school my home room was Mrs. Craig’s art class at Oakland High School in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. I took all the art courses Mrs. Craig offered. I particularly liked to draw streets and buildings using perspective. I used rulers to draw lines to the vanishing point and then drew objects using the lines as guides. Fast forward and we find architects generating projects using significant technical assistance, including AI assistance. Nothing wrong with any of this. Indeed, there’s a lot right with it: it improves the quality of one’s work and increases his productivity.

This includes ideas generated by the technology. Consider that any accomplished blues or jazz player will incorporate into their inventory the licks of other blues and jazz players. This isn’t plagiarism. It’s an important part of growing one’s inventory of musical knowledge. What’s the difference between human-generated and AI-generated blues and jazz licks? I don’t see any. I use an AI box that generates bass and drums based on chord patterns and progressions I feed to the machine and then improvise over it. I could publish the results. Problematic? No. It’s an effect. Pedals are effects. Putting strings on a piece of wood is an effect. The principle remains the same across time. And it is my composition. I am the author.

These are growing pains. Panic occurs whenever new technology comes along. We have been here many times before. And we will in the future. Many embrace the new technology and advance the field. Others resist. But eventually almost everybody comes around to the new technology and it becomes normalized. The only ethical problem is passing off AI-generated content (text and images) as human generated. Beyond that, AI is a tool like anything else. There will always be Luddites and technophobes, but even here, most of them come around to a technological advancement over time; they have to because they will be left behind if they don’t. People worry about being replaced by AI, but they are far more at risk of being replaced by humans who use AI.

The survey reports faculty concerns. I get it, and agree with many of their concerns. But it’s heartening that so many of my colleagues recognize the usefulness of the latest technological advancement. It means that the period of panic and resistance will be short-lived and the college can get on with riding the technological wave—a wave that will benefit everybody in the longterm.