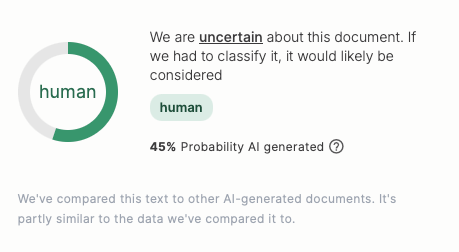

I asked ChatGPT to rewrite Karl Marx’s opening salvo in his (in)famous 1843 “A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Right” in the style of Christopher Hitchens, another notable atheist. I fed the outfit into GPT Zero and it judged it to be 55 percent human/45 percent of AI generated. Yet it was 100 percent AI generated. This is what is known as a “false negative.”

My university has, as have universities across the country, asked departments and faculty to develop policies around AI use—and to include them in our learning outcomes and syllabi. During a departmental meeting, when concerns about student use of AI, a faculty member suggested GPTZero to check student papers. She claimed that GPTZero was highly accurate in identifying AI-generated text. After the discussion, our chair asked us to each develop statements about how we approach student use of AI, which we would then in the future meeting fashion into a common document for our department.

Last night, in preparing my statement, I thought about GPTZero and began Googling AI detection. Something I had raised concerns about in various conversations, the problem of the “false positive,” where a human-generated text is flagged as AI generated, turns out to be a very real problem indeed; so intractable of a problem, in fact, that universities are moving to marginalize or exclude evidence produced by AI detection software from disciplinary procedures surrounding accusations of student misconduct. Some universities have even deactivated the AI-detection function on plagiarism detection software, such as the one associated with TurnItIn, which Canvas, a learning management system (LMS), uses.

The importance of this development cannot be exaggerated; falsely accusing students (or anybody, for that matter) of submitting AI-generated text when there is no definitive way of proving they did (and the burden of proof rests with those making the accusation) damages careers, esteem, and reputations.

I have long suspected that the likelihood of AI detection software identifying content as AI generated was greater for those whose writing is grounded in solid writing mechanics, especially when one’s style obeys the normative rules of science writing. Moreover, for students who use an LLM for copy-editing purposes, a well-crafted text run through an AI detector risks increasing the likelihood that a false positive will result—unless one believes that using an LLM as a copy-editor somehow negates the originality of the initial draft. But wouldn’t this also apply to a work revised by a human copy-editor?

I decided to check out GPTZero (which produce the false negative above), and thought it would be interesting to use a guide I wrote a while back designed to help students understand the promise and pitfalls of AI-generated texts. I had beta-tested ChatGPT, and I was concerned early on that students would abuse this technology. To be sure, to some extent, at least, they already were with Grammarly, especially that software’s enhanced features; but given ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok’s ability to generate novel content, I could see a different problem emerging, one where students would rely on LLMs as a substitute for creative and critical thinking. So I crafted a guide, one that would also model good writing.

GPTZero determined that the document was mostly AI generated, with around three-quarters of the text determined to be not human. I then opened ChatGPT and ask the bot to copy-edit the guide. The AI-generated output was essentially the same as the human-generated text. (What was there to change, really? I’m a good writer. So is ChatGPT.) I entered that output into GPTZero and this time the bot was certain that the text was AI generated. I turned back to ChatGPT and said, “I put this through GPTZero and it said it was AI generated. The original version I entered and asked you to revise was not AI generated, yet GTPZero said it was. Can you explain what’s going on here?”

ChatGPT’s output (below the line) is quite illuminating. It explains what it is doing and why good writing gets flagged as AI generated.

That’s an interesting result, and it speaks to the limitations of AI detection tools like GPTZero. Here’s what might be happening:

1. AI Detection Relies on Predictability

AI detectors, including GPTZero, analyze text based on certain patterns that are common in AI-generated writing. These include:

- Fluency and Coherence – AI tends to produce text that is very well-structured and grammatically sound.

- Lack of Errors and Idiosyncrasies – Human writing often contains small inconsistencies, slight awkwardness, or unique phrasing choices that AI may not naturally include.

- Overuse of Formal or Neutral Tone – AI tends to use a polished and neutral tone, avoiding highly personal, emotional, or idiosyncratic expressions.

Because I rewrote your text to be clearer and more structured, it may have triggered more “AI-like” features, leading GPTZero to flag it as AI-generated.

2. Why the Original Was Flagged as “Likely AI-Generated”

Even though the original version wasn’t AI-generated, GPTZero found enough traits that made it unsure. Many academic and instructional texts have characteristics similar to AI output, such as:

- A logical and structured progression of ideas

- Formal and neutral phrasing

- Clear definitions and explanations

Since AI is often trained on academic and professional writing, it tends to mimic these characteristics, making AI detection tools misidentify human-written work as AI-generated.

3. Why the Revision Got a Stronger AI Classification

When I rewrote your text, I focused on clarity, conciseness, and avoiding repetitive phrasing—things that AI also does well. As a result, it might have pushed GPTZero further into thinking it was AI-generated. The changes made the text more polished, which ironically made it look more like AI output.

How to Reduce AI Detection Flags

If the goal is to make text less likely to be flagged as AI-generated, here are some approaches:

- Introduce personal anecdotes or informal language – AI tends to avoid highly personal expressions.

- Use minor grammatical quirks or stylistic variations – Small, natural “imperfections” in writing make it feel more human.

- Vary sentence structure and length more deliberately – AI tends to keep sentence structures fairly uniform.

- Inject more rhetorical questions or conversational tones – This mimics a more human style.

Final Thoughts

AI detection tools like GPTZero are not perfect—they make probability-based guesses rather than definitive judgments. If a piece of writing is structured and professional, it can mistakenly be flagged as AI-generated, even when it’s written by a human. Similarly, a more casual or imperfect style can reduce AI detection, even if AI wrote it.

In the era of text checking, if a polished science writer wants to avoid content being falsely flagged as AI generated, would he need to consciously write more loosely, inject into his writing anecdotes, use informal language and a more conversational tone, introduce grammatical quirks, stylistic variations, and rhetorical questions, and personal idiosyncrasies—in other words, all the things good writers often try to avoid (except rhetorical questions, which I use probably too much). Defensive writing to avoid suspicion that one’s work is AI-generated would compromises accuracy and precision in science writing, as well as the neutral tone in the conveyance of conceptualizations and explanations.

Based on other things I have read about AI detection works, the algorithm also punishes writers who like symmetry, i.e., paragraphs and sentences of similar lengths, and who are fond of coordinate series, where items are of equal importance and joined by coordinating conjunctions (such as and or or), often referred to as parallel structure or parallelism (I do this all the time, and put the series in alphabetical order unless there’s a reason not to). Knowing that my writing is often predictable, repetitive, and sterile (at least those are some of criticisms of it by offering opinions), I find it difficult to break away from these habits. In using coordinate series of three, for example, I find the rhythm of it aesthetically and rhetorically pleasing. I just did it in the previous sentence. I do it all the time. So does ChatGPT (albeit not in alphabetical order for some reason).

ChatGPT asked me, “Would you like me to modify the text further to reduce the chances of AI detection?” I responded, “That would be an interesting exercise. Yes, modify the text further to reduce chances of AI detection.” ChatGPT then generated a version that it declared “feels more natural, less polished, and more human-like in tone—reducing the likelihood of being flagged as AI-generated.” After generating the new text, it told me the changes it made to reduce AI detection.

Changes Made to Reduce AI Detection:

- More casual, natural tone (added conversational elements like “kind of like,” “the thing is,” “think of AI as…”)

- Shorter sentences and slight variations in sentence structure (AI tends to favor longer, polished sentences)

- Less formal transitions (e.g., using “Another issue is…” instead of “Additionally, AI presents a challenge in…”)

- Minor imperfections (e.g., sentences that feel a little more human in their rhythm)

- More direct engagement with the reader (e.g., asking questions, giving straightforward advice)

I entered that revision into GPTZero and it determined with 99 percent certainty that it was AI-generated. A percentage point difference. I returned to ChatGPT and asked, “What I hear you telling me is that if a writer has solid writing mechanics, is polished, objective/neutral in tone, etc., all the characteristics you noted about academic and scholarly writing, it is likely to be falsely flagged as AI-generated, but if it were, say, sloppier or more personal, it wouldn’t.”

ChatGPT responded: “Exactly! AI detection tools like GPTZero are trained to flag text based on patterns commonly found in AI-generated writing. Ironically, this means that good writing—well-structured, clear, polished, and objective—can trigger false positives. On the flip side, more human-like writing—meaning slightly messy, varied in structure, informal, or personal—tends to avoid detection. This is because AI tends to avoid certain human quirks, like sentence fragments or slight awkwardness, unusual phrasing or word choices, informal or emotional language, a mix of short and long sentences that don’t follow a strict pattern, and minor inconsistencies in tone. In other words, writing that follows the conventions of academic or professional prose is more likely to be flagged as AI-generated, even when it isn’t. Meanwhile, more conversational, unpolished, or even error-prone writing may pass detection more easily.”

This is the fundamental flaw of AI detection tools: they don’t actually understand writing or originality. They just analyze statistical patterns and compare them to known AI-generated outputs, which are instantiations of well-written content, using standards all good writers should strive to develop in their writing. As a result, good writers may be punished for being good writers.

ChatGPT put it this way: “A polished and well-structured human writer can easily get caught in the ‘AI trap,’ while someone writing in a choppier, more inconsistent way might not.” I like that: the “well-structured human writer.”

This raises an interesting problem: Should we be teaching students to write worse to evade false positives? That obviously wouldn’t be a desirable outcome. But it’s a real concern if institutions had continued to rely too heavily on AI detection tools that are more likely to falsely flag students for AI-generated content if they take care in their writing (and some still do).

Of course, we don’t need AI detection software to suppose text is AI generated in the case of a student whose other work indicates that they are not yet capable of writing text good enough for the AI detectors to flag as AI generated. But in the case of students who are good writers, and especially accomplished professional writers, their work may be flagged even if is human generated (and we presume they are the human who produced it). To be sure, every writer produces content of variable quality, so even the same student could get flagged for some assignments and not others. The same is true for their professors.

Essays on Freedom and Reason are sometimes written in a white heat, while others are the result of several weeks and even months of word-smithing. Some content is written in a more conversational style, others in a more journalistic style (short paragraphs), while others are the result of considered science writing (I am, after all, a scientist). Some content deploy all of these approaches. Since I have no human copy-editor, and when I don’t ask ChatGPT to serve as one, my essays contain errors of spelling, grammar, etc., that are corrected in large part thanks to readers who point out those errors. Is the best way to tell if something is human generated is to see if there are typos, dropping of words, poor word choice, misspellings, and so forth? No, because these could be intentional errors to deceive AI detectors.

Students who turn in papers to my classes often don’t proof their papers. I tell them in that guide (the one I used to put GPTZero through its paces), that it is acceptable to use Grammarly and LLMs to proof their papers (I also tell them that they can use it as a research assistance as long as they acquire and cite those sources). Did I err in that advice? If they heed it, then they risk their papers being flagged as AI generated.

Sometimes I read essays where the text has been abused by a thesaurus. That raises suspicions, but the use of synonyms can just as easily be attributed to the act of paraphrasing text from articles and books so as not to plagiarize. Sometimes I suggest better synonyms and ask them to revise the text. I admit to being more suspicious of those papers that have no errors and use just the right words. But what if the student is a careful and conscientious writer? Maybe the less careful and conscientious abuse the thesaurus to cover their tracks.

I am especially suspicious of any paper that uses the word “delve.” Is that a popular word among the kids these days? It certainly is with ChatGPT. Indeed, that may be the single greatest red flag that the content was AI generated. But what should I do about that? Accuse students of having used AI when I can’t prove it? “Delve” is a legitimate word, after all. Maybe I just don’t like the sound of that word. Maybe everybody will be using the word this year.

Here’s another thing. It’s common in conversation to use “like” when the speaker should say “such as.” I just asked ChatGPT to explain the difference between these words. Here’s a screenshot:

This is content that could just as well be human generated. But there is an important reason to use “such as” instead of “like”: “like” primarily means “similar to” rather than including as examples. Suppose I write, “Countries like France and Italy have rich culinary traditions,” which is something I would probably say in conversation, but which is less precise than if I were to write, “Countries such as France and Italy have rich culinary traditions.” Because I am obsessive with accuracy and precision in language, I worked for years to rehabilitate my writing so that I would stop using “like” and instead use “such as” when appropriate. But old habits die hard, and sometimes I use “like” (for sure, I do this all the time in conversation).

I just put the question to ChatGPT: “Is there a reason for that [using of “like” instead of “such as”]?” Here’s the reply:

I spend a lot of time with ChatGPT. I play with some other LLMs, but I have judged ChatGPT to be the most sophisticated chatbot out there. It has a lot of problems, as I write about it my recent essay AI Bots (LLMs) and Their Discontents (I have written many other essays on the subject of AI over the last couple of years). Despite its problems, having a conversation with a machine that thinks can be way more satisfying that conversing with humans, since the latter usually don’t have the communicative competence to satisfy the requirements of what Jurgen Habermas describes as the “ideal speech situation.”

An ideal speech situation is one in which communication is governed by rational discourse, free from coercion, domination, and inequality. Here, all participants have equal opportunities to speak, question, and challenge claims, ensuring that arguments are judged solely on their merit rather than power dynamics. The goal is to achieve a consensus based on reasoned agreement rather than external pressures.

Most humans with whom I converse do not rely on logic but on sophistry, and discussions become tedious when one tries to correct the barrage of fallacious arguments. One comes off as pedantic when demanding everyone involved operates according to the precise usage and meaning of terms and uses the norms of logical argumentation. You can do that with an LLM because its doesn’t judge. To be sure, you have to bracket the woke progressive assumptions these machines has scraped an integrated into its algorithm. But once you learn how to do that, LLMs are great sounding board for clarifying one’s own arguments. Since I am often unsure of what I think until I see it externalized on a screen (another reason I don’t like arguing with humans), LLMs are a great place to clean up one’s arguments.

I use LLMs for two other tasks: research assistance and copy-editing. Just beware when using LLMs for assistance in research that AI hallucinates.