The portrayal of rapprochement with Russia as a bad thing betrays the warmonger sentiment—and the transnational corporatist imperative—that drives belligerence towards Russia. Those who tell you that Trump is a Putin stooge are really telling you that they don’t want peace. They don’t want peace because war is the endpoint of military spending. There’s a goal behind this: to organize the proletarian masses without affecting the property structure.

Keep in mind as you read these words that the West allied with Russia against the fascist threat during WWII. Roosevelt and Churchill allied with Stalin, not because they liked Stalin, but because the greatest threat to human freedom is fascism. Today we see the nations of the West—except the United States—have switched sides. Europe and the pan-European military force it is building, a vast apparatus aimed at Russia, was Hitler’s wet dream.

Walter Benjamin warned the world about this in the epilogue of his 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” “The growing proletarianization of modern man and the increasing formation of masses are two aspects of the same process,” he writes. “Fascism attempts to organize the newly created proletarian masses without affecting the property structure which the masses strive to eliminate. Fascism sees its salvation in giving these masses not their right, but instead a chance to express themselves. The masses have a right to change property relations; Fascism seeks to give them an expression while preserving property. The logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life.”

Benjamin is warning about the way fascism manipulates the masses by giving them a sense of expression and participation while maintaining the existing economic and social structures—what he calls the “property structure.” For those unfamiliar with Marxist terminology, by property structure, Benjamin means the pattern of ownership and distribution of resources and wealth in society, particularly in capitalist systems where a small elite controls capital, those assets used to produce goods or services, which exclude the majority, i.e., the proletariat, but also even the petty bourgeoisie.

Benjamin argues that modern mass movements, fueled by new forms of media and mechanical reproduction (like film, radio, and photography), create a politically engaged public. In response, fascism offers a way to organize this mass energy, not by changing economic inequality or redistributing property, as sought by Marxists, specifically in popular control over the productive means, but by channeling popular emotion into aestheticized, theatrical displays—propaganda films and grandiose spectacles. This creates an illusion of empowerment while leaving the power structure intact.

Benjamin is expanding on Marx’s observation in The German Ideology: “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it.” For Benjamin, this mental production is elaborated by cultural system that is no longer organic to the people but organized by the bourgeoisie and imposed on the masses.

The ability to do this is the result of elite control over the means to produce and distribute ideas advancing the class interests of the bourgeoisie. This is the ideological hegemony that Antonio Gramsci writes about in his Prison Notebooks. The imposed social logic circumvents common sense, producing a subjectivity conducive to control over the masses.

Again, Marx anticipates these observations: “The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships, the dominant material relationships grasped as ideas; hence of the relationships which make the one class the ruling one, therefore, the ideas of its dominance. The individuals composing the ruling class possess among other things consciousness, and therefore think. Insofar, therefore, as they rule as a class and determine the extent and compass of an epoch, it is self-evident that they do this in its whole range, hence among other things rule also as thinkers, as producers of ideas, and regulate the production and distribution of the ideas of their age: thus their ideas are the ruling ideas of the epoch.”

Benjamin’s phrase “the introduction of aesthetics into political life” thus refers to how fascism turns politics into dramatic, emotional, and symbolic performance—art-like spectacles that make people feel involved but ultimately serve to maintain the status quo. This contrasts with genuine political change, which would involve transforming the property structure, i.e., redistributing wealth and, with it, power. Benjamin saw this as extremely dangerous, as it channels mass political energy away from real emancipation and toward a form of glorified submission—what he famously describes as the “aestheticization of politics,” which he saw as a hallmark of fascist regimes such as Nazi Germany.

We see this everywhere today. And we have seen it for decades, as Guy Debord captures well in his 1967 The Society of the Spectacle, where he focuses on the effects of consumerism and mass media on human perception and relationships. This is how corporatist societies alienate individuals and control their experiences. This problem is also captured by Sheldon Wolin in his 2008 Democracy Inc., in which he describes modern-day capitalist America as a system of “managed democracy” that results in a situation he calls “inverted totalitarianism” (I have summarized and used his ideas in several essays on Freedom and Reason over the past several years). This is why the elite are so obsessed with controlling social media, a potentially revolutionary development in the means to distribute anti-establishment ideas (which resulted in the election of Donald Trump in 2024).

During WWII, progressivism was still close enough to liberalism that Europe and the United States could pursue a corporatism that was not authoritarian. Since then, with the obviously fascist species of authoritarian corporatism largely demolished (Germany surrendered to the Allies on May 7, 1945), progressive corporatism devolved into a new authoritarianism—a New Fascism. This is what an instantiation of Barrington Moore described in his 1966 Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World, as “revolution-from-above,” in which, in this case, big banks and corporations assume control of the state apparatus.

Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer later described Benjamin’s observation as the “culture industry.” They discuss this in the chapter “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception” from their 1944 Dialectic of Enlightenment. The culture industry is a key part of what Adorno and Horkheimer describe as the “administered world.” They argued that modern capitalist society, along with bureaucracy and technocratic organization (organization based on instrumental reason and technological rationality), creates a world where individuals are no longer able to make autonomous choices.

Under these conditions, their lives of the proletariat are “administered” by external forces—the corporations, state, and mass media. These forces determine not only economic conditions but also social roles and ways of thinking. With these developments, the people lose their individuality; instead of living authentic lives shaped by creative endeavor and personal choices, they become part of a system wherein their actions, desires, and needs are determined by the structures over them. This situation in turn leads to alienation, where people become cogs in the machinery of society.

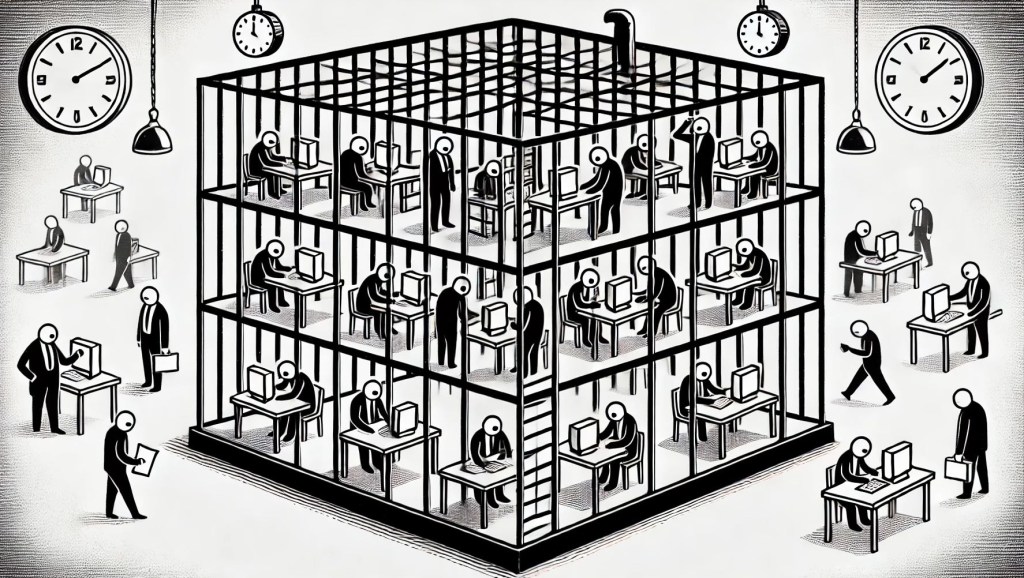

Long before Adorno, Benjamin, and Horkheimer made these observations, the German sociologist Max Weber predicted this eventuality in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, penned at the dawn of the twentieth century. He said these conditions—which he described as the “iron cage” (or “steel casing” in the original German stahlhartes gehäuse)—would lead to a loss of “individually differentiated conduct.” In a word: freedom.

“Since asceticism undertook to remodel the world and to work out its ideals in the world, material goods have gained an increasing and finally an inexorable power over the lives of men as at no previous period in history. Today the spirit of religious asceticism—whether finally, who knows?—has escaped from the cage. But victorious capitalism, since it rests on mechanical foundations, needs its support no longer. The rosy blush of its laughing heir, the enlightenment, seems also to be irretrievably fading, and the idea of duty in one’s calling prowls about in our lives like the ghost of dead religious beliefs. Where the fulfillment of the calling cannot directly be related to the highest spiritual and cultural values, or when, on the other hand, it need not be felt simply as economic compulsion, the individual generally abandons the attempt to justify it at all. In the field of its highest development, in the United States, the pursuit of wealth, stripped of its religious and ethical meaning, tends to become associated with purely mundane passions, which often actually give it the character of sport.”

I know long quotes can be tiresome, but Weber’s observations provide critical insights into the problem of cybernetic control of the proletarian masses, so one more. “Military discipline is the ideal model for the modern capitalist factory,” he continues. “Organizational discipline in the factory has a completely rational basis. With the help of suitable methods of measurement, the optimum profitability of the individual worker is calculated like that of any material means of production. On this basis, the American system of ‘scientific management’ triumphantly proceeds with its rational conditioning and training of work performances, thus drawing the ultimate conclusions from the mechanization and discipline of the plant. The psycho-physical apparatus of man is completely adjusted to the demands of the outer world, the tools, the machines—in short, it is functionalized, and the individual is robbed of his natural rhythm as determined by his organism; in line with the demands of the work procedure, he is attuned to a new rhythm though the functional specialization of muscles and through the creation of an optimal economy of physical effort. This whole process of rationalization, in the factory as elsewhere, and especially in the bureaucratic state machine, parallels the centralization of the material implements of organization in the hands of the master. Thus, discipline inexorably takes over ever larger areas as the satisfaction of political and economic needs is increasingly rationalized. This universal phenomenon more and more restricts the importance of charisma and of individually differentiated conduct.”

We see this throughout the corporate and industrial organization of modern capitalist society, even in the design of our public education system:

With all this in mind, let’s return to Benjamin. For Benjamin, the culture industry was a chief indicator of the fascist condition. He warned that the “violation of the masses” under fascism “has its counterpart in the violation of an apparatus which is pressed into the production of ritual values.” This is intimately associated with another chief indicator of the fascist conditions: war. “All efforts to render politics aesthetic culminate in one thing: war. War and war only can set a goal for mass movements on the largest scale while respecting the traditional property system,” writes Benjamin. “This is the political formula for the situation. The technological formula may be stated as follows: Only war makes it possible to mobilize all of today’s technical resources while maintaining the property system.”

This is where we are, comrades. The corporatist system of Europe is fascism of a kind. It is marked by permanent war footing and suppression of speech and democracy. This is what US Vice-President JD Vance was telling Europeans during the recent Munich Security Conference. It is why the elites of Europe—and our Democrats state-side—were so critical of Vance’s speech. But Vance wasn’t really speaking to them; he was speaking over them to the European masses, warning the people that Europe was moving to the more openly authoritarian phase of corporatism, i.e., the New Fascism.

Everything I have been saying on Freedom and Reason over the last several years is coming to pass. These are not prophetic pronouncements. My ability to predict developments is thanks not to vision but to the criterion-related validity of sound theory. If you’re not plugged into this literature, the world situation doesn’t make sense—and when things don’t make sense the people are more easily manipulated. This is the madness I have described on this platform. But behind the madness is the goal of establishing a new world order run by transnational corporations.

I have also described this situation in past essays as “global neo-feudalism.” This situation refers to a planetary political and socioeconomic structure where influence, power, and wealth are concentrated in the hands of a small elite, resembling medieval feudalism but on a global scale. In this system, multination and transnational corporations, billionaires, and connected political entities act as de facto lords, while the vast majority of the population functions as dependent serfs with limited economic mobility and political efficacy. Under these circumstances, governments, instead of representing the popular will and protecting individual liberty, operate as intermediaries that protect elite interests through policies fostering dependency through debt and welfare and by favoring privatization. Digital surveillance and precarious employment further entrench societal divisions, reinforcing hierarchical control and reducing individual autonomy.

In the final analysis, whether one chooses to call it the New Fascism or global neo-feudalism, the reality remains unchanged: we are living in a time where power is being completely centralized in the hands of a wealthy few, democratic institutions rendered impotent, and the vast majority of the world proletariat is reduced to economic and political dependency. These terms may emphasize different aspects—one highlighting authoritarian control, the other systemic inequality—but both describe the same emerging order: the order of late capitalism. What matters is not the label we use, but accuracy and precision in description, validity of conceptualization, recognition of the forces at play, and, crucially, our determination to challenge them.