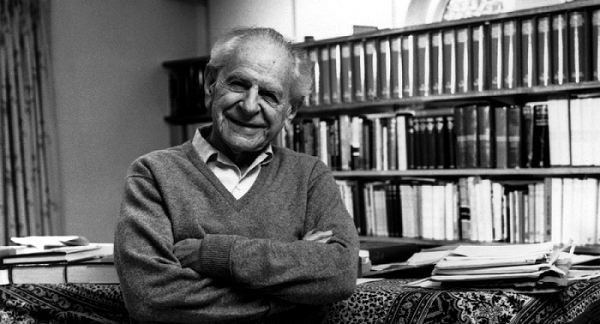

“[I]f we are uncritical we shall always find what we want: we shall look for, and find, confirmations, and we shall look away from, and not see, whatever might be dangerous to our pet theories. In this way it is only too easy to obtain what appears to be overwhelming evidence in favor of a theory which, if approached critically, would have been refuted. In order to make the method of selection by elimination work, and to ensure that only the fittest theories survive, their struggle for life must be made severe for them.” —Karl Popper, The Poverty of Historicism

On February 14, Vice President JD Vance delivered a speech at the Munich Security Conference sharply critical of European nations for their restrictions on free speech and association (I have appended video of the speech to the bottom of this essay). He highlighted instances such as Sweden convicting a Christian activist for burning a Quran, and the European Union threatening to shut down social media during times of civil unrest the moment its censors spot what they judge to be “hateful content.” Vance argued that these actions undermine democratic values and warned that the US might reconsider its support for countries that do not uphold fundamental freedoms. (See my recent essay covering the conference here: Vance and Zelensky at the Munich Security Conference: Two Visions of a Future Order of Things. See also The Emperor is Naked: The Problems of Mutual Knowledge and Free Feelings.)

Two days later, CBS’s 60 Minutes aired a segment featuring German prosecutors discussing the country’s stringent laws on online speech (I have appended video of the interview to the bottom of this essay). The interview highlighted that, in Germany, public insults and the dissemination of false information online are criminal offenses, with authorities arguing that such measures are necessary to protect democracy and maintain civil discourse. This approach contrasts sharply with the United States, where the First Amendment safeguards a broader spectrum of speech, including expressions considered hateful or offensive, not trusting such designations to an office of the commissar. By confirming the truth of Vance’s speech, CBS underscored the differences between the two nations regarding the boundaries of free speech and the role of government in regulating online content.

The defense of free conscience, speech, association, and assembly is not merely a philosophical commitment to natural rights (a point I have frequently emphasized in previous essays on Freedom and Reason); it is a practical necessity for the pursuit of truth. Science, the most reliable method for understanding reality, depends on open inquiry, unfettered debate, and competition of ideas. It cannot function in an environment where authorities dictate acceptable thought, speech, or association. Any law or policy that restricts these freedoms does not just infringe on individual rights—it undermines the very process by which knowledge advances. When authorities suppress dissenting views, however mistaken they may seem at the time, they stymie the correction of error, the refinement of theories (explanations, predictions), and the discovery of new truths.

In Germany, hate speech laws at the federal level prohibit incitement to hatred against protected groups, including trans identifying individuals, while defamation (Section 186 StGB) and insult (Section 185 StGB) laws can apply to cases of “deadnaming” and “misgendering” or if deemed deliberately harmful. Scientifically, gender identity has the same ontological status as angels or thetans; punishing a person for deliberately using the appropriate pronoun is thus an act of suppressing accurate language for the sake of an ideology. The law wraps itself in moral language about forbidding intentional affronts to personal dignity, but in doing so, it elevates ideology over science. Defenders of the laws will clarify that deadnaming and misgendering are not blanket criminal offenses; they fall under existing legal provisions if used maliciously. But that’s the problem: how does one insisting upon accurate language avoid the appearance of malice given the assumptions upon which the law is grounded? We should put the matter bluntly: In Germany, one is not allowed to be a bigot—and the German state will define what counts as bigotry.

This is an intolerable situation. A society that punishes certain thoughts, forbids discussions on certain topics, or compels individuals to adopt a doctrine does not merely limit personal liberty; it criminalizes the tolerance necessary for intellectual progress and rational action. The history of science and philosophy testifies to the power of controversy—today’s heresies often become tomorrow’s orthodoxies—and this transformation only happens when dissent and heterodoxy are allowed. When institutions impose ideological conformity, they do not just silence individuals; they sabotage the mechanisms that allow truth to emerge from error. And some truths will hurt some feelings. Free expression and association are not merely moral goods—they form the foundation upon which all genuine knowledge rests.

As a libertarian, I regard the suppression of speech, thought, and association as markers of the authoritarian condition—a situation that is incompatible with both freedom and reason. While we are obliged to tolerate arguments, conversations, and opinions, including those favorable to or advocating for authoritarianism, we must not tolerate or abide by laws and policies that suppress either libertarian or authoritarian viewpoints. To do so would be to accept the very premise that authority may dictate what is permissible to think or express.

I want to take care here to differentiate my stance from that of Karl Popper and his paradox of tolerance thesis. My argument is that we should tolerate all ideas in open discourse but refuse to comply with laws that make genuine tolerance impossible. The proper response to authoritarian controls on speech is not submission but resistance—precisely because the preservation of an open society depends on our dissent. Popper’s paradox, outlined in his 1945 The Open Society and Its Enemies, argues that unlimited tolerance leads to the destruction of tolerance itself. Specifically, he contends that a tolerant society must be willing to defend itself against intolerant forces that, if left unchecked, would suppress tolerance altogether. He asserts that while all ideas should be debated in an open society, if intolerant ideologies seek to abolish debate through force or coercion, they should not be tolerated. Popper’s defenders will object that he does not argue for suppressing mere advocacy of authoritarian ideas; rather, he warns against tolerating those who would use force to eliminate freedom. To my ears this sounds like a distinction without a difference.

My critique of Popper’s argument is thus: If a society claims the authority to suppress “intolerant” views, the next question becomes: Who decides what is an intolerant view? If the answer is the state, then we empower precisely the kind of authority that suppresses free speech and open discourse under the guise of protecting tolerance. Popper’s argument is therefore paradoxically authoritarian itself—by advocating for the suppression of certain ideas, he effectively grants a governing body the power to determine which ideas are too dangerous to be expressed. This favors some speech over others, and that judgment falls to those whose ideology determines what speech is favorable and what speech is not.

This logic manifests in contemporary German law, where the government criminalizes certain forms of speech, including Holocaust denial, Nazi symbolism, and offensive speech deemed harmful to public order. While Germany justifies these laws as necessary to prevent extremism and protect democracy, they nonetheless rest on the assumption that the state can and should regulate discourse to prevent certain ideas from gaining traction. The result is a legal framework where authorities punish people not just for direct incitement to violence (which is not protected speech even in the United States) but for expressing opinions the state deems dangerous—an approach fundamentally at odds not only with a strict libertarian defense of free speech but also with the very freedom required for a legal and institutional framework for the conduct of science and other knowledge production.

Thus, from a libertarian standpoint, any attempt to police speech—even speech advocating authoritarianism—is itself authoritarian. The principle of free speech only holds if it applies to all viewpoints, including those some find abhorrent. Once the state begins deciding which ideas are too intolerant to be tolerated, it assumes precisely the kind of power that libertarians argue should not exist. My argument goes beyond Popper’s paradox: I am not merely calling for resistance to authoritarian policies; I am rejecting the very legitimacy of the state’s role in adjudicating which ideas may be expressed at all. The state in a free and open society must defend free speech and assembly; otherwise, it is an authoritarian state, and society is no longer free and open.

I recognize that critics will argue that libertarianism is itself an ideological framework with assumptions about the state’s proper role in society. My point is not that libertarianism is a singular truth, but rather that it affirms the singular truth that authoritarianism negates free and open society. You cannot simultaneously proclaim support for a free and open society, on the one hand, and then, on the other, restrict arguments, ideas, opinions, and assembly. Several principles undergird the libertarian position, such as non-aggression and individual sovereignty, which constitute the necessary preconditions for a free society, but the paradox I am identifying is incontrovertible.

History abounds with examples of how laws and policies suppressing speech hinder scientific and intellectual progress. I have often pointed to the suppression of Galileo’s heliocentrism by the Catholic Church and how that delayed scientific progress. In that case, restrictions on speech aimed to entrench religious dogma. Another example, particularly relevant given Germany’s restrictive attitude towards speech and association, is how the Nazi regime weaponized speech restrictions to consolidate power and eliminate dissent. After rising to power in 1933, the Nazis swiftly enacted laws criminalizing criticism of the state, which they used to suspend civil liberties, for example, the Editors’ Law of 1933 forbade non-Aryans from working in journalism.

The Reich Press Chamber, operating under the German Propaganda Ministry, took command of the Reich Association of the German Press, the professional body governing journalism in Nazi Germany. With the implementation of the Editors Law, the association maintained strict records of journalists deemed “racially pure,” systematically barring Jews and individuals married to Jews from the profession. To practice journalism, all editors and reporters were required to register with the Reich Press Chamber and adhere to the ministry’s directives. Officials demanded absolute compliance, dictated content, and enforced censorship. Paragraph 14 of the law explicitly prohibited editors from publishing any material that could be perceived as undermining the strength of the Reich, either domestically or internationally.

The strict control over journalism under the Reich Press Chamber and the Nazi Propaganda Ministry enabled medical atrocities to continue without widespread public knowledge or dissent. By monopolizing the press, the regime suppressed reports of unethical human experiments, euthanasia programs, and other crimes against humanity, while propaganda justified what was known about these actions as necessary for national health and racial purity. The exclusion of oppositional journalists ensured that dissenting voices were silenced, and instilling fear in those who remained, knowing that they risked severe punishment for disobedience. With the press fully controlled and access to international reporting restricted, most Germans had no access to independent accounts of the horrors occurring in concentration camps, hospitals, and psychiatric institutions. Even those who suspected wrongdoing had little means to confirm or share their concerns. As a result, the regime’s control over journalism directly facilitated medical crimes such as the T4 euthanasia program, allowing large-scale atrocities to continue in secrecy with minimal risk of exposure or resistance.

By controlling speech, the Nazis ensured that dissenting voices—whether from intellectuals, ordinary citizens, or political opponents—remained silent, preventing any meaningful resistance from forming. This censorship did not protect society; rather it created an environment where propaganda thrived unchallenged, reinforcing dangerous myths and justifying atrocities. By the time overt acts of persecution escalated, from the Nuremberg Laws to the Holocaust, public discourse had become so tightly controlled that opposition was nearly impossible.

Given this historical context, how can the contemporary German state rationally defend its speech codes while acknowledging the dangers of authoritarianism—all in the name of defending democracy? One might object that contemporary German law in this area is not as severe as German law under the Nazis, but the objection is beside the point. If restrictions on speech helped enable one of history’s most repressive regimes, why should we believe that similar restrictions (and the similarity is growing stronger over time) will prevent rather than facilitate authoritarian control? After all, contemporary restrictions are themselves markers of authoritarianism! The burden of proof lies with those who claim that suppressing speech is necessary for a free society. What proof could possibly justify negating civil liberties? History clearly demonstrates the opposite.