“It is not that the historian can avoid emphasis of some facts and not of others. This is as natural to him as to the mapmaker, who, in order to produce a usable drawing for practical purposes, must first flatten and distort the shape of the earth, then choose out of the bewildering mass of geographic information those things needed for the purpose of this or that particular map…. But the map-maker’s distortion is a technical necessity for a common purpose shared by all people who need maps. The historian’s distortion is more than technical, it is ideological; it is released into a world of contending interests, where any chosen emphasis supports (whether the historian means to or not) some kind of interest, whether economic or political or racial or national or sexual.” —Howard Zinn

Given Trump’s announcement of reciprocal tariffs, it may be useful for readers to know that, like Alexander Hamilton, Abraham Lincoln was pro-tariff. Hamilton advocated for tariffs to promote American industry and generate revenue for the federal government. In his Report on Manufactures (1791), he proposed using tariffs and subsidies to encourage domestic production and reduce reliance on foreign goods. He believed that a strong manufacturing sector was essential for economic independence and national security. His advocacy of this approach was not just about protectionism. Hamilton also wanted to ensure steady government revenue. Hamilton was not alone among the Founders in his advocacy of tariffs. George Washington, John Adams, and James Madison (the primary author of the Constitution, the Federalist Papers, and the Bill of Rights) were, as well.

Lincoln’s views on tariffs were likewise shaped by his commitment to economic protectionism, particularly to support the industrial development of the United States and protect domestic businesses and working-class Americans from foreign competition. This contrasted sharply with the Democrats, especially Southern Democrats, who were opposed to tariffs. The Democrats represented sectors that benefitted more from world capitalism than domestic economic development. Since Democrats were party of slavery, they were not concerned with the fate of the proletariat but with maintaining the aristocracy and atavistic feudal arrangements. A party’s choice of comrades is important to keep in mind—actually, not just in rhetoric and on the surface level. Democrats maintained a culture of paternalism, upon which black slaves were dependent and made subservient. One strategy Democrats used to control blacks was fatherlessness, substituting plantation owners for the fathers of black children.

We thus see that the Republican Party aligned with the vision of the protectionists, those who sought economic independence, industrial development, and national security, whereas the Democrats sought world capitalism in which industry and the proletariat were subject to the vagaries of the world market. This division was not insignificant. Indeed, it is still significant, as I will come to in this essay. From the beginning, this difference in philosophy was the divide that contributed to the growing tensions between the North and South in the run up to the Civil War—the real American revolution that overthrew the aristocracy and the slavocracy. Unfortunately, to the detriment of the American project, in the aftermath of war, Democrats reasserted their power via the corporate state, which replaced the slavocracy with a new paternalism, indeed a new aristocracy, which is today manifest in a party desperately trying to save the globalization project from the populist revolt it necessitates (if man is to be free and society democratic)—a populist movement that seeks the reclamation of the American Republic as envisioned by the Washington, Madison, and Lincoln. What Democrats called “Redemption” was a counterrevolution.

This discussion also necessitates an understanding of the emergent problem of mass immigration and the goals of the transnationalists who defend the practice of open borders, especially in light of Trump’s immigration policies. I have written about this history before (see, e.g., An Architect of Transnationalism), but it bears revisiting here. As I did in previous essays, I focus on the early twentieth century philosopher Horace Kallen. Kallen alerted the nation to the globalization project because he endorsed it and wanted to socialize the idea to enable the new aristocracy to achieve hegemony over the people. When you hear people decry the metaphor “Melting Pot” and celebrate in its stead the “Salad Bowl,” you’re hearing Kallen’s rhetoric. Kallen was one of the leading organic intellectuals of the corporate class that desired these ends. Crucially, Kallen was not only an advocate of mass immigration, he strongly opposed to the idea of a national identity.

Kallen introduced the concept of “cultural pluralism,” what we call today “multiculturalism,” which opposes assimilationism and celebrates the coexistence of multiple cultures within a single nation, envisioning America as a federation of distinct ethnic communities rather than an integrated people. Indeed, the man desired the devolution of the modern nation-state and the establishment of a one-world government run by technocrats in its place. Kallen used the term “trans-nationalism” (he may have coined the term) to advance the corporate dream of one-world government. This is a vision that goes back to eighteenth century, to the French philosopher Henri de Saint-Simon’s desire for global corporatist arrangements, or what he called “socialism.” (He even proposed a version of the United Nations.)

How do the transnationalists advance their agenda? They strive to capture the administrative apparatus of the federal government and society’s sense-making institutions and put them under the control of corporate power—and make this appear to be a progressive and therefore desirable development. Over the centuries, progressives (social democrats in Europe) have transformed the administrative apparatus into a permanent political establishment, the administrative state, which they use to steer nations towards the desired ends by circumventing the will of the people. Whatever party is in power, the agenda continues. However, the story of how this unfolded is a crucial part of understanding possibility, and the more historical details provided, the more we are helped in understanding the fallacy I will discuss in a moment, that is the fallacy of the parties of the US polity having flipped (I discuss an aspect of this here: Republicanism and the Meaning of Small Government). Once this myth is debunked, it is easy to see where the parties have stood historical on the question of globalism and administrative rule—and to see that the public has been fed a crude revisionist history functional to the globalist agenda.

The transnationalists were having their way at the beginning of the twentieth century. Woodrow Wilson, a Democratic who served as president from 1913 to 1921, was opposed to protectionism. He believed in free trade and advocated for eliminating and reducing tariffs to promote international commerce. Wilson’s administration signed the Underwood-Simmons Tariff Act in 1913, which lowered tariff rates significantly. It also reintroduced the income tax, which the Supreme Court had previously stuck down. This time the income tax was secured by constitutional amendment (overwhelming supported by Democrat majority states). Wilson argued that high tariffs benefited special interests at the expense of consumers and hindered the growth of global trade. This aligned with his vision of a broader vision of a cooperative world order. The obvious expression of this was his advocacy for the League of Nations after World War I.

Wilson also played a key role in the establishment of the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve Act, signed into law by Wilson on December 23, 1913, was ostensibly a response to the banking panics that had occurred in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In reality, it put the nation’s financial fate in the hands of the banking and corporate elite. Wilson and his administration pushed for a central banking system that would exist beyond democratic control. The Federal Reserve Act established a decentralized system of twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, which would oversee and regulate commercial banks and manage the money supply. Wilson’s support of the Federal Reserve Act was part of his broader progressive agenda to “reform” the financial system and protect consumers and businesses from “economic instability” (how has that worked out?).

Wilson’s stance on immigration was a bit more complicated because of his racism, which was not particularly favorable to non-European immigrants. He supported measures like the Immigration Act of 1917, which created an “Asiatic Barred Zone,” sharply limiting immigration from much of Asia. He believed that immigration should be in line with the desired racial hierarchies that have historically marked the designs of the Democratic Party. So, while Wilson was not opposed to mass immigration, his policies were shaped by the segregationist trends of the late nineteenth an early twentieth century (the Redemption sought by Democrats). It is worth noting that, domestically, Wilson’s administration establishment of racial segregation in federal offices. It is important for the historical record to recognize that Wilson, a progressive, was a segregationist.

Following the war and the failure of the League of Nations, Republicans were able to push back against the transnationalist agenda. In the 1920s, Republicans embraced protectionist economic policies, aiming to shield domestic industries from foreign competition. Under the leadership of presidents like Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge, the government implemented high tariffs, such as the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922, which raised duties on imported goods to protect American farmers, manufacturers, and workers. The goal was to encourage domestic production and reduce reliance on foreign goods. Thus, protectionism continued as a central feature of the Republican economic agenda, reflecting a broader desire for economic self-sufficiency and autonomy after World War I.

Republicans also cut off the flow of immigrants into the United States, thus impeding a key part of the globalist plan. In 1924, Republicans secured the Immigration Act of 1924, also known as the Johnson-Reed Act, that limited the total number of immigrants to around 150 thousand per year, a sharp reduction from previous numbers allowed. Quotas were set at two percent of the total population of each nationality in the US according to the 1890 census, which had a much higher percentage of Northern and Western Europeans compared to the 1920s population.

Thus, the law was designed to maintain the cultural integrity that a slower pace of assimilation had established. Those entering the country would then have stable communities with which to integrate. In other word, the overall cap would allow for more orderly integration. Thus the effect would obviously favor those established populations. The nation was dealing with the very serious problem of social disorganization and the criminogenic conditions it produced, seen in high rates of gang violence, interpersonal violence, and juvenile delinquency. It was prudent from a reasonable understanding of the experience of mass immigration that immigration should be sharply limited and that new arrivals associated with established populations would allow for more orderly assimilation and thus reduce the problem of social disorganization and the problems associated with it. The following decades bore out their understanding.

Progressive Democrat made a major power move in the 1930s, taking advantage of the world capitalist crisis (the same crisis that led to the rise of progressivism’s authoritarian corporatist cousin, fascism), and with the New Deal of the charismatic Franklin Roosevelt entrenched progressivism by enlarging the administrative state. As a result, except for a handful of Republican presidents whose commitment to the American Creed the masses found welcoming, the party dwelled in the wilderness for decades. The exceptions are important to the story, however, so I will discuss them forthwith.

Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SCAEF) during World War II, was deeply troubled by his experience in his subsequent post as Commander in Chief, which had permitted him to see the entire apparatus, the military-industrial complex and the technocracy most concerning, waiting until his farewell address to warn the nation about the danger posed by the emergence of what Columbia professor C. Wright Mills identified a few years earlier as a “power elite.” Despite his popularity, Richard Nixon resigned in his second term, concerned that if he fought back against the power elite, he’d suffer the same fate as John Kennedy and brother Robert, who were assassinated for their plans to dismantle the administrative state (Nixon talked frankly about this concern in his latter days). Ronald Reagan was safe because he was managed by an establishment operative named George H. W. Bush, former chief of the CIA (and founding Trilateralist), who was selected as Reagan’s vice-president. Reagan wasn’t the same man he had been during the 1960s and 1970s, which would have caused the establishment concern (Reagan, a former Democrat, was Barry Goldwater’s greatest surrogate).

However, once George Bush Senior assumed the presidency in 1989, the globalization project came into full bloom. He and Bill Clinton ushered in the new world order progressives had sought since the Kallen days. Suspicious of Al Gore, the establishment engineered the election of George Bush Junior in 2000 and staffed his White House. They did the same in 2004, denying John Kerry the election and securing Bush’s reelection. (Both Gore and Kerry subsequently became stooges for the transnational agenda.) If you ever wondered why Barack Obama, who served as president from 2009-2017, continued Bush’s policies, it’s because these were the establishment’s policies and Obama was their selection for president, not just to continue the transnationalist agenda, which includes the neoliberal and neoconservative projects, but also to push the emerging DEI regime to cover the realities of capitalist accumulation, the concentration and deepening of corporate power, the elaboration of the hegemonic strategy of cultural pluralism, and soften the image of empire.

These developments are not only rooted in the New Freedom and New Deal regimes. The transnationalization project was ramped up during Great Society regime of the 1960s. The nation was reopened to mass immigration mid-decade, and, via control of the culture industry, the emerging mass media domain, and federal command of the educational system, including higher education, the power elite projected its power to such an extent that it assumed control over speech, writing, and thought. This through-going control over intellectual production is the problem this essay is addressing: the revision of history and the indoctrination of the masses to conform with the grand narrative progressives had composed. To say that it was Orwellian is not an exaggeration. Today, generations of young people have been taught to loathe the American Republic and its history, and to see key historical figures through a lens that either changes their appearance or blurs them out.

Karl Marx captures the dynamic well in these words from The German Ideology (1845-46): “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it. The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships, the dominant material relationships grasped as ideas; hence of the relationships which make the one class the ruling one, therefore, the ideas of its dominance. The individuals composing the ruling class possess among other things consciousness, and therefore think. Insofar, therefore, as they rule as a class and determine the extent and compass of an epoch, it is self-evident that they do this in its whole range, hence among other things rule also as thinkers, as producers of ideas, and regulate the production and distribution of the ideas of their age: thus their ideas are the ruling ideas of the epoch.”

But there’s good news. Something happened on the way to world government. A populist movement began gaining steam in the late 1980s and early 1990s, not just in the United States, but across Europe. I will focus on the United States for this essay. The historical marker is the defeat of Democrat candidate Hillary Clinton, who had served as Secretary of State under Obama and was next in line to continue the transnationalist project was to be the next iteration. However, by 2016, populist nationalism, grassroots resistance to the globalization project, was ascendent, and Donald Trump prevailed in that year’s election (I explain the emergence of populist nationalism in detail here: The Red Shift and What it Means).

Trump’s presidency was hobbled by his political naiveté, especially by his over-reliance on establishment functionaries, but more so by an all-out war by the establishment waged at multiple levels—corporate media propaganda, and deep state activities, and lawfare (I chronicle these developments in numerous posts on Freedom and Reason). Using these tactics and organizing a color revolution, the establishment engineered Trump’s defeat in 2020. However, thanks to the opening of social media (Elon Musk and his take-over of Twitter, now X, deserves the lion’s share of the credit here) and the delegitimization of the legacy media in the wake of this development, which had played a key role in all the engineering I have been talking about, and the experience of a feeble and inept president in the form of Joe Biden (who had played a key role in globalization throughout his fifty-year career as a politician), the people not only reelected Trump in 2024, but elected a Republican Senate and kept in place a Republican House.

Today, thanks to tireless resistance, the majority can see the scheme. Recently, DOGE and a full-scale government audit have helped the public learned how, via its various agencies and departments, the administrative state pushes out revenues derived from the populace to wealthy families and individuals around the world who establish non-government organizations to enrich themselves and entrench their power and influence under the guise of humanitarianism. Progressives and social democrats have engineered regional and global power directed by transnational corporate organization. This is the real oligarchy, and for decades both Democrats and Republicans served its interests. The people can also see this thanks to the rise of an alternative media, not only Steve Bannon’s influential War Room, but a plethora of blogs and podcasts freely available on their devices. In this way, the people have disrupted elite control over the production of ideas that Marx describes in the quote I provided earlier in this essay.

This point cannot be overemphasized. Key to restoring the integrity of the constitutional republic our founders established at the end of the eighteenth century, and that the Republicans salvaged from the decadence of the slavocracy nearly a century later, is exposing the way the scheme works and then using mutual knowledge to marshal the will for deconstructing the administrative state. The power of technology and the weakening of legacy structures of control have given the populace new tools and renewed passion to fight corporate state control.

It was fully expected that the corporate state would resist being exposed and the prospect of losing their power and thus their agenda—and their privileges. Democrats tell public that the populists and nationalists are trying to burn down the government, that right wing forces are disrespecting the Constitution, and that the nation is headed towards a constitutional crisis. But what the power elite is really fighting for is continued control over the administrative apparatus they use to enrich the corporate state and advance the globalist project. This is why they have fought so hard to maintain hegemonic control over the production of ideas. It’s the populists and nationalists who are the ones respecting the Constitution and thwarting the transnational project that will, if allowed to succeed, end the American Republic. It is crucial for the people to see these matters clearly and grasp the task at hand.

Crucial to expanding the scope of mutual knowledge is debunking something I note earlier: the conventional narrative that the Democratic and Republican parties “flipped” after the 1960s, with Democrats allegedly adopting the legacy of Lincoln and Republicans assuming the mantle of the old Southern Democrats. However, as the reader can see, a closer examination of American political history reveals a more complex transformation, one rooted in ideological shifts, structural economic changes, in particular the rise of the corporate state and capitalist regionalization and globalization, and the ongoing struggle between populism and progressivism. For the sake of mutual knowledge, I want to finish this essay by summarizing and, in some cases elaborating, what I have written so far.

From its founding, the Democratic Party was the party of the agrarian elite in the South, advocating for the preservation of a plantation economy that relied on slavery. This quasi-feudal system was deeply hierarchical and resisted industrialization and democratic participation. In contrast, the Republican Party emerged in the 1850s as a coalition of abolitionists, entrepreneurs, and free labor advocates who sought to dismantle the slave economy and establish a more dynamic, market-driven society. Notably, the economic and political philosophy of the early Republican Party was not lost on contemporary socialist thinkers (not the Saint-Simon variety, which is not socialism at all but technocracy). Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, writing for the Republican Party newspaper, the New York Tribune, supported the Union cause in the Civil War, viewing the struggle as one between a reactionary aristocracy and a rising free-labor economy. This international support underscores the early Republicans’ alignment with the desire for economic liberty and political democracy over entrenched hierarchy that threatened the capitalist elite. The New York Tribune is an exemplary of the early attempt to establish media for the people.

As readers have seen, after the Civil War, Democrats adapted to changing realities by aligning themselves with an emerging corporate and bureaucratic elite (Richard Grossman’s history is useful here, which can find by searching for his lecture on Law and Lore on the Internet). By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, progressivism—rooted in central planning and technocratic control—became the dominant force within the Democratic Party. This shift was exemplified by Wilson’s vision of governance, which sought to replace democratic participation with expert rule, culminating in the expansion of administrative agencies.

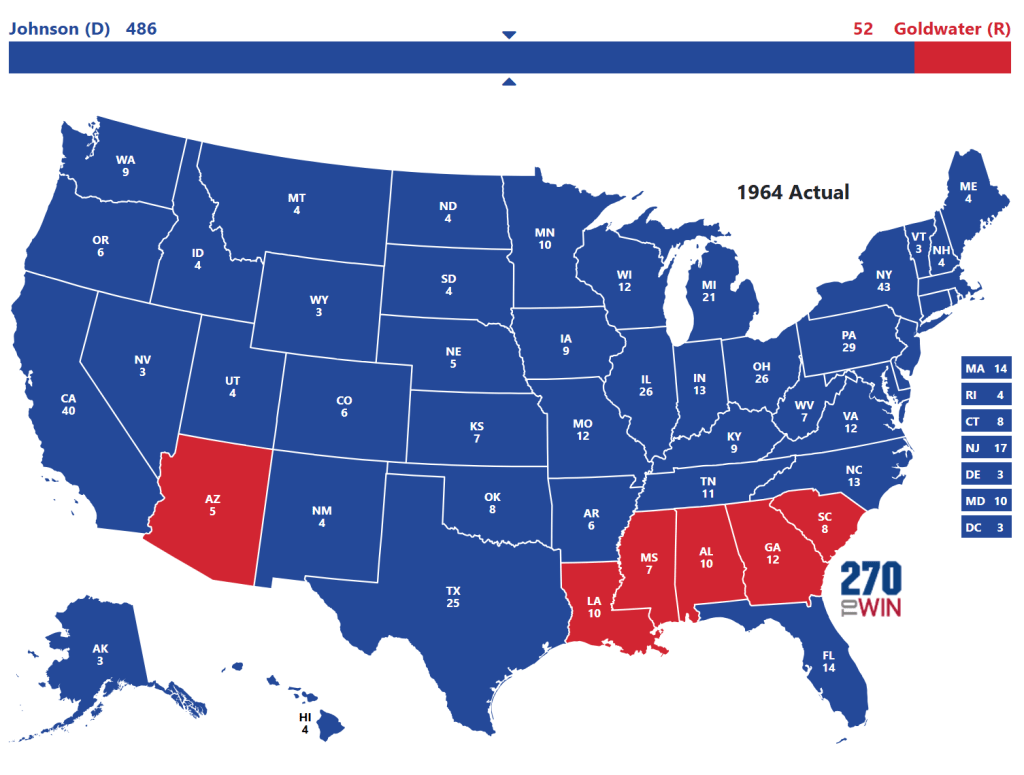

During the 1920s, the Republican Party, still rooted in a populist vision of national cohesion, championed immigration restrictions to stabilize American labor markets and maintain cultural unity. These policies laid the groundwork for a nation-state framework that later enabled the Civil Rights Movement by ensuring that economic and political participation was not undercut by labor competition in a split labor market, as well as the world market. It is worth noting that the Civil Rights Act of 1964, often credited solely to Democrats, was filibustered by Southern Democrats and passed largely due to Republican support.

Roosevelt’s New Deal represented the final consolidation of the Democratic Party as the party of centralized corporate control, institutionalizing the administrative state and displacing Republican populism. This shift was reinforced by post-war internationalism, with Democratic leadership spearheading initiatives like the United Nations (realizing Saint-Simon’s dream), projects that subordinated national sovereignty to global governance. Republicans, meanwhile, struggled to maintain political relevance amid this sea change.

The Bush and Obama years represented the zenith of technocratic governance, where both parties converged on a shared agenda of globalization and administrative expansion. The disillusionment with this consensus set the stage for the populist resurgence embodied by Donald Trump, whose political movement rekindled the spirit of economic nationalism and skepticism toward bureaucratic overreach. Trump’s presidency challenged the realignment of Republican leadership, a betrayal of the Party of Lincoln, as well as the founding vision of America, with corporate interests and internationalist policies, instead championing tariffs, deregulation, and a reassertion of national sovereignty. This shift was met with fierce resistance from entrenched elites, who employed legal, media, and institutional mechanisms to counteract his influence.

Despite these challenges, Trump’s political success—culminating in a Republican-led government—signaled a broader ideological shift away from the technocratic status quo and toward a renewed vision of democratic republicanism. The establishment’s aggressive opposition, including attempts to delegitimize his presidency and policies through legal and political maneuvering, underscores the stakes of this ongoing struggle. Thus, the narrative that contemporary Republicans merely adopted the old Southern Democratic ethos, despite being crude and false, obscures the deeper reality: the Republican Party today represents a revival of the original populist-nationalist principles that animated Lincoln’s coalition, reclaimed by Republicans during the 1920s, and then marginalized during progressive hegemony. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party, long a bastion of aristocratic control, evolved into the party of globalized technocracy and transnational corporate power, and these loyalties have been central to the party throughout its history. The Republican Party hasn’t really changed, only derailed from time to time. The Democratic Party is the same party it has always been, its desire for racial control periodically reimagined (what replaces affirmative action and DEI awaits to be seen).

As the political landscape continues to evolve, looking forward, figures like Vice-President JD Vance and other populist conservatives represent the next phase in this ideological battle. Vance’s blistering speech before European leaders Friday at the Munich Security Conference demanding that they listen to their voters is a preview of coming attractions. Whether the Republican Party can fully reclaim its historic role as the champion of democratic participation and economic independence remains to be seen, but the realignment now underway suggests a profound challenge to the status quo of the past century. A crucial moment will be the midterm elections in 2026. That depends on Trump, Vance, and the team around them (conservatives and liberals working together) having early legislative and policy successes. Today, Trump maintains his popularity among the masses, but, as we have seen, just as it did in the aftermath of the Civil War, and during the capitalist crisis of the 1930s, populist-nationalism today faces considerable opposition. The people can take nothing for granted.

* * *

At the top of this essay, I note the words of Howard Zinn from his popular revisionist text, A Peoples History of the United States. Zinn correctly acknowledges that historical writing inherently involves selection and emphasis (as I have here). His framing wants us to believe that this process is not just unavoidable but ideological. Perhaps. But the problem is not merely that his work is ideological, but that it is partisan, deliberately shaping narratives to serve contemporary political objectives. While Zinn described his politics as democratic socialist, he did implore people to vote for Barack Obama.

In A People’s History of the United States, Zinn does not just emphasize overlooked perspectives (his justification for writing the book in the way he does); he simplifies or omits complexities that do not fit the narrative he sets before us. His approach reflects a partisan strategy of mobilizing history for present-day political activism. He selects facts and frames them in ways that reinforce a progressive worldview, to be sure draped in anti-establishment rhetoric, downplaying ambiguities and counterpoints in the subjects to which he chooses gives his treatment. This is the work of an activist-historian who constructs history as a tool for political ends.

The broader problem with progressive history is that it portrays itself as a corrective to mainstream narratives while engaging in moral absolutism, omission, and oversimplification. If all history involves selection, the question becomes: to what end is that selection made? A historian’s role is ideally to illuminate complexity, not historicize contemporary political dogma. But progressive history prioritizes present-day ideological alignment over historical nuance, making it less a scholarly endeavor and more a means of political persuasion—and not always by the force of its reason, but by often manipulating emotion.

I want to be clear. Zinn does not explicitly make the argument that the parties flipped. I am using his justification for working the way he did to illustrate the problem. An example of the argument I have critiqued (I am confident Zinn would have agreed—not with my critique but the target of it) is the work of Dan T. Carter. Many years ago, when I first taught race and ethnic relations, I used Carter’s The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics. This was when I was still in the antiracism camp. I confess, my selection of the book was an ideological choice.

Carter’s central argument is that Wallace, a populist, adopted the rhetoric of racial segregation, and that the Republican Party, especially Nixon and later Reagan, adopted Wallace’s themes, albeit more subtle versions of such appeals—framing racial issues in terms of “law and order” and as opposition to “big government” rather than explicitly segregationist. In this way, Carter contends, Southern white conservatives, once loyal to the Democratic Party, realigned with the GOP. Historian Kevin Kruse makes a similar argument, arguing that white Southerners and many Northern whites abandoned the Democratic Party in response to the civil rights movement, particularly after the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act. He contends that Republicans, through Nixon’s Southern Strategy, courted these voters by using coded racial appeals — “states’ rights,” “law and order,” and “forced busing.”

The interpretation that opposition to big intrusive government, the desire to return to a more robust federalism, support for law and order (America was experiencing a crime wave during these years), and the desire of parents to keep their children closer to home are code words for racism, moreover that Democrats’ embrace of affirmative action and the rhetoric of antiracism did not represent a turn to identitarian policies centered on ginning up racial animosity, is emblematic of the partisan ideological approach that marks progressive historiography.

It’s not about race. It’s about opposition to big intrusive government and all the rest of it. It’s also about rejecting the progressive tactic of demonizing white people for wanting to be free and safe and for refusing to be enlisted in the identitarian project.