A cockroach in the concrete, courthouse tan and beady eyes

A slouch with fallen arches, purging truths into great lies

A little man with a big eraser, changing history

Procedures that he’s programmed to, all he hears and sees

Altering the facts and figures, events and every issue

Make a person disappear, and no one will ever miss you

Rewrites every story, every poem that ever was

Eliminates incompetence, and those who break the laws

Follow the instructions of the New Ways’ Evil Book of Rules

Replacing rights with wrongs, the files and records in the schools

—Dave Mustaine and Danny Ellefson, “Hook in Mouth” (1988)

Before the election, at a small gathering on my front porch, when it was still warm outside, a neighbor expressed his concern about the uninformed people reading and believing misinformation and disinformation on X. Platforms like X, he said, should be policed to remove misinformation and disinformation for the good of society. Given his politics, pro-Democrat and progressive, I felt I could make assumptions about who he thought should serve as commissar. Recently, on Facebook, a former colleague expressed a similar sentiment in the wake of Facebook dropping its fact-checking regime. I asked him whether the “lot of people out there who believe whatever they read, hear or are told at face value” (his words) should believe the fact-checkers. His answer: “[I]f something is verified by multiple reliable sources then yes.”

But how would the people who take things at face value know the fact checkers are reliable? Knowing his politics, I noted that one of Facebook’s factchecking services was Check Your Fact, a service associated with right-wing magazine The Daily Caller, co-founded by Tucker Carlson. The service’s tagline is “We check the facts so you don’t have to.” From the organization’s site: “The Daily Caller’s fact-checking team is funded by The Daily Caller’s general news budget, as well as revenue generated through advertising. Check Your Fact is also partially funded by Meta, which contracts the outlet to do third-party fact-checking on Facebook and Instagram.” I posed the question to my former colleague: “Were you confident during Meta’s factchecking era that an organization owned by former Fox News host and current Trump advocate Tucker Carlson would steer those who take things at face value in the right direction?” Obviously, it is a rhetorical question.

In 2019, Science, a publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), published an exposé on Check Your Fact in its section ScienceAdviser, “Facebook fact checker has ties to news outlet that promotes climate doubt.” (I presume you received the memo that there is to be no doubt about climate change.) Science is the same magazine that published the editorial “Transgender health research needed,” in which the authors told its readership as fact that “TGD [transgender and gender diverse] people have gender identities that differ from society’s expectations based on sex assigned at birth. Gender-affirming care consists of personalized health interventions that help patients achieve their goals of decreasing gender dysphoria and increasing gender euphoria. Hormone therapy, surgeries, and mental health services help TGD people live in alignment with their gender identity and expression, consistent with the accepted biomedical ethics principle of respect for autonomy, articulated by philosophers Tom Beauchamp and James Childress in 1979.” Presumably, Science is the sort of a reliable source those who take things on face value are supposed to trust—in contrast to The Daily Caller’s Check Your Fact service Meta hired to check facts.

Recall the censorship on social media platforms of COVID-19 information that contradicted the prevailing narrative developed by the medical industrial complex and states and government and nongovernmental organizations around the world. Social media platforms, news outlets, and government agencies took steps to suppress or flag content that diverged from what was portrayed as the mainstream scientific consensus, particularly when it came to alternative treatments, the origins of the virus, and vaccine efficacy. Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube enforced policies that often removed posts or accounts that promoted conflicting or “unverified information.” “Experts” argued that this censorship was necessary to prevent the spread of misinformation that could jeopardize public health. When Elon Musk assumed control of Twitter (now X), he ended the practice (on this and several other matters, such as the expression of gender critical views). In the wake of Donald Trump’s re-election, Mark Zuckerberg has followed suit, ending Meta’s relationship with fact-checkers.

Why is there so much angst over these developments? From the elite side, this isn’t hard to understand. “Advertiser concern,” is a euphemism for the concerns of corporate governance. Corporations do a lot more than move product. They manage perceptions. They govern the populace. They can’t do that when platforms allow for the free trucking of information. But perhaps popular trepidation over these developments is not hard to understand, either. A population conditioned to accept on face value the claims of “multiple reliable sources” cannot determine for itself its beliefs. Not knowing what to believe produces anxiety, which is often projected onto the “lot of people out there who believe whatever they read, hear or are told at face value.” Not seeing their own egoism in supposing that, while they know what the truth is, others cannot be trusted to know the difference between what true information and something else, they leave that matter to those with whom they share ideological affinity, assuming that the fact-checkers in Meta’s employ fit the bill. In other words, they themselves take at face value “facts” from sources purported by some authority to be reliable. It is a hopeless paradox.

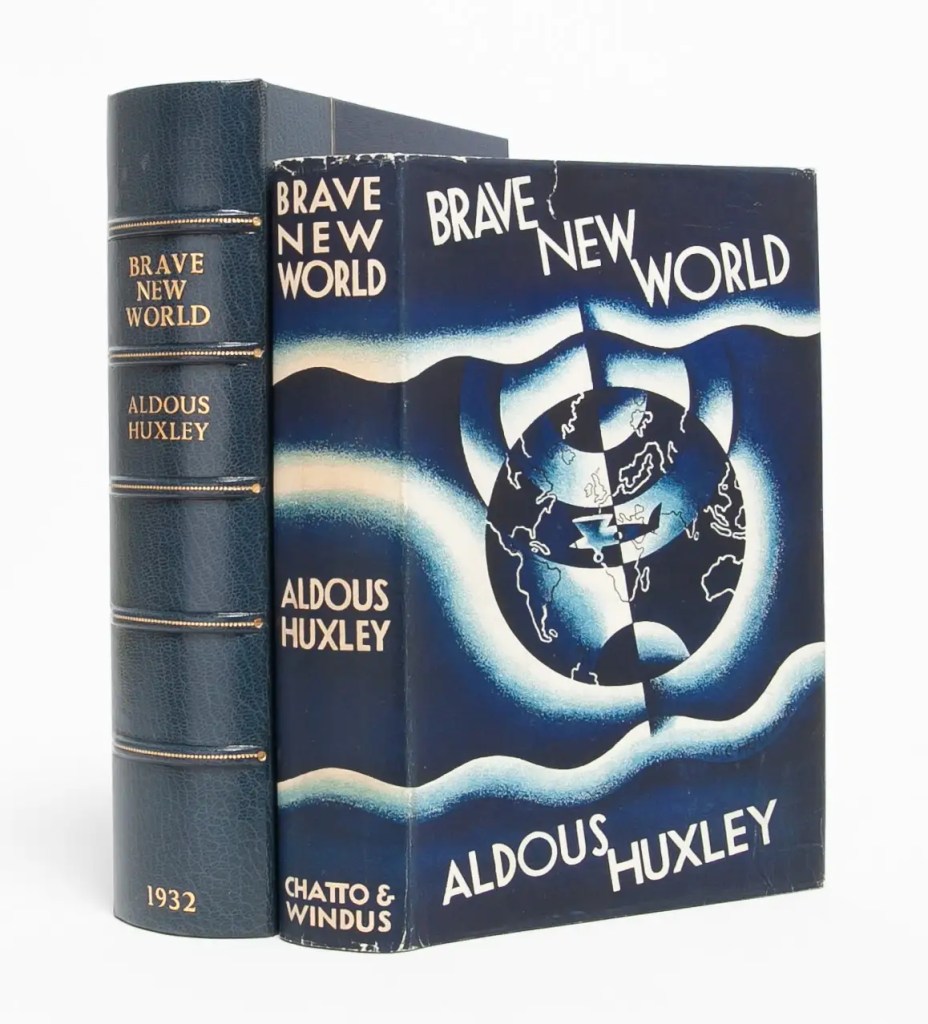

In Brave New World, Aldous Huxley introduces the concept of “mandatory perception,” a feature of the World State’s relentless efforts to control how individuals feel, think, and view reality. Through pervasive methods, such as hypnopedia, or sleep-teaching, which is learning by hearing while sleeping or under hypnosis, citizens are conditioned from birth to accept societal values without question. Conditioning implants beliefs that shape mass perceptions of the world, creating a population that sees conformity, obedience, and stability as the highest virtues. Individuality and personal interpretation are systematically suppressed in Huxley’s dystopia. The World State fosters an environment where deviation from the collective mindset is not just discouraged but unsettling, even threatening. By programming people to perceive their world in narrowly defined ways, the World State ensures its citizens remain compliant and content, incapable of challenging the status quo. The result is a society where perception is not merely shaped but dictated, leaving no room for alternative viewpoints or independent thought.

Today, this is known as “perception management.” Perception management is the deliberate effort by corporations and governments to influence how individuals or groups interpret information, events, or situations. It’s a strategy used in advertising, marketing, and public relations, in politics, to justify military action, etc., to shape public opinion, suppress dissent, and maintain control over narratives. The process involves carefully curating messages, emphasizing certain aspects of reality, omitting or downplaying others, to guide the audience toward a desired understanding or reaction. At its core, perception management leverages the psychological principles of cognitive bias and framing. By controlling the context in which information is presented, those managing perceptions can influence how people interpret that information. When one knows it, he sees it everywhere. A political campaign might highlight a candidate’s achievements while deflecting attention from controversies, crafting an image that aligns with voters’ aspirations. Perhaps this is expected. Is it expected that the entire media apparatus would highlight controversies to deflect attention from the candidate’s achievements and virtues to turn voters against him?

Often subtle—always subtle to those who don’t know what’s happening—, this practice has profound effects, particularly when used to sway public opinion on contentious issues. The rise of digital platforms has amplified the reach and complexity of perception management. Social media algorithms, targeted advertising, and influencer endorsements create environments where tailored narratives can spread rapidly and persuasively. This dynamic makes it increasingly challenging for individuals to distinguish between authentic information and content designed to manipulate their perceptions, underscoring the importance of media literacy (the opposite of factchecking) and skepticism (central to critical thinking) in navigating today’s information landscape. The regime of factchecking is not only a strategy for imposing Huxley’s mandatory perception, but also for obscuring the manipulation inherent in the present workings of social media.

One can see this power in the way the media apparatus can turn on a dime and cause tens of millions of people to believe or disbelieve something today about which they held the contrary view the day before. Things that were never true become always true. The paradigm is the case of Donald Trump.

Before entering politics, former President and current President-elect Donald Trump, a prominent real estate developer from Queens and a television personality, had expanded the family business into a global brand, becoming synonymous with luxury and opulence through high-profile properties, casinos, and ventures. Known for his larger-than-life persona, Trump was a frequent figure in entertainment (talk shows, SNL, etc.), sports, and tabloids, sports, rubbing elbows with celebrities and politicians while cultivating an image as a charismatic billionaire and shrewd dealmaker. In the 2000s, Trump became a cultural icon through his role as the host of the reality TV show The Apprentice, which showcased his commanding personality. However, when Trump announced his run for president in 2015, the media’s portrayal underwent a dramatic shift. Once celebrated as a pop culture icon, he became a polarizing figure in American politics. Far from framing the man as a voice for disenfranchised Americans and a disruptor of the political establishment, the media and partisans portrayed him as a fascist (even comparing him to Hitler) and a racist.

Why this shift occurred is easy enough to explain. Trump was adored as long as he was on the outside the sphere of corporate state power. His fierce independence and views on political economy and foreign policy were tolerated because they could have no effect on policy and world affairs. The people who adored him were believed to be well under the control of the power elite. When he entered politics, that changed. His meteoric rise in the ranks for Republican contenders terrified elites, not only because o his views, but because he brought tens of millions of disaffected Americans with him. He gave them a voice when they were suppose to have no voice. So the hegemony machine flipped the switch, and Trump was transformed. A face became a heel. His wickedness was bottomless. He was a Russian stooge, determined to sell out America to the arch-villain Vladimir Putin. He was a rapist. An insurrectionist. A dunderhead and a kook. Anything and everything said about him was believed by tens of millions, and no amount of factchecking could change their opinion. For those who disbelieved the mandatory perception, their wickedness was a bottomless, which justified harassing the red MAGA hat wearer or disinviting an uncle to Thanksgiving Dinner—or worse: open disappointment that an assassin’s bullet missed its target.

The efficacy of hegemonic power tells us that a large proportion of the population already lives in Huxley’s World State. The popular turn against Trump is one example. There are many others. “MeToo” set feminism on its head. Racism is ubiquitous. Over a number of years queer theory redefined gender, but one day we just seemed to know that affirming the obvious—that a man cannot be a woman—would rightly be met with negative sanction and shame, that we would even think of ourselves as terrible persons for having even thought this, even though everybody thought it only a little while ago. The very fact that we know without being told that this or that is an entirely unacceptable opinion, a belief that can have no purchase in polite society, testifies to this power.

The magic of this power lies in its ability to erase what came before it, since what came before it, if allowed to be the subject of mutual knowledge, negates the thing we’re all supposed to know as eternal truth. Indeed, the wholesale and immediate reconstruction of common sense is perhaps the scariest aspect of hegemonic power. And that is why the fact-checker has no place in a free and democratic society.

Put your hand right up my shirt

Pull the strings that make me work

Jaws will part, words fall out

Like a fish with hook in mouth