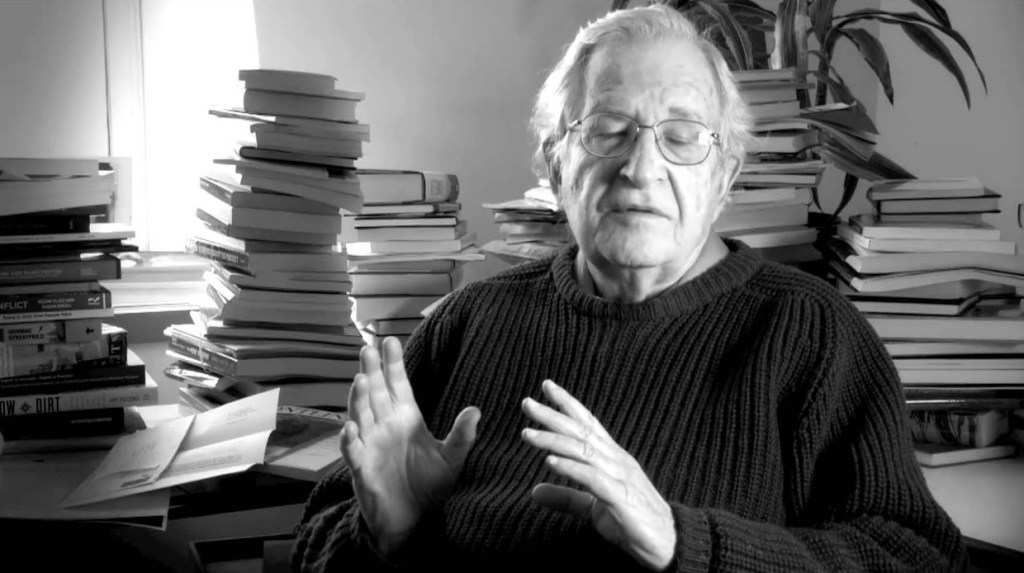

Noam Chomsky on postmodernism:

“If you look at what’s happening, I think it’s pretty easy to figure out what’s going on. I mean, suppose you’re a literary scholar at some elite university or an anthropologist or whatever. If you do your work seriously, that’s fine, but you don’t get any big prizes for it. On the other hand, you take a look over in the rest of the university, and you got these guys in the physics department and the math department, and they have all kind of complicated theories, which, of course, we can’t understand, but they they seem to understand them. And they have principles and they deduce complicated things from the principles and they do experiments, and they find either they work or they don’t work. And so that’s really impressive stuff, so I want to be like that too. So I want to have a theory in the humanities, you know, literary criticism, anthropology, and so on. There’s a field called ‘theory.’ We’re just like the physicists. They talk incomprehensibly, we can talk incomprehensibly. They have big words, we’ll have big words. They draw far reaching conclusions, we’ll draw far reaching conclusions. We’re just as prestigious as they are. Now if they say, well, look, we’re doing real science and you guys aren’t, that’s white, male, sexist, bourgeois, whatever the answer is. How are we any different from them? Okay. That’s appealing.”

Chomsky is correct on the nonsense hailing from literary studies and philosophy. Critical race theory, queer theory, etc., aren’t theories at all but ideologies that work at cross purposes with science. They are designed to rationalize political goals that threaten prevailing and just normative systems.

The core premise of critical race theory is that law founded on individualism is a white supremacy construct and that race-based social justice—with its atavistic ethics of intergenerational and collective guilt—should replace it. The “logic” of the “theory” rests on the fallacy of misplaced concreteness, reifying demographic categories and reducing flesh and blood individuals to personifications of statistical abstractions. For example, because, on average, white men have more wealth than black men, all white men are “privileged.” In the real world, there are black men with vast sums of money while white men live under bridges with no money at all.

The core premise in queer theory is that gender is a social construct independent of natural history. This is said to advance a project to normalize paraphilias. Queer theory’s premise is easily falsified by scientific investigation. Indeed, the objectivity and materiality of gender is one of those rare settled questions in the sciences. But gender activists deny or obscure the truth because truth is an obstacle in their political path. As with critical race theory, I have written extensively on this subject on the pages of Freedom and Reason.

However, compelling Chomsky’s critique of postmodernist literary theory, his extension of this critique to anthropology, sociology, and other social sciences fails. Theories in the social sciences are indeed distinct from those in natural sciences like physics or biology, as I explain in my essay The Four Domains of Reality: Sketching an Analytical Model of Emergent Complexity, but this distinction reflects the different natures of the phenomena studied, not an absence of rigor or intellectual merit. Theory plays a crucial role in the social sciences by providing frameworks for understanding cultural phenomena, human behavior, and social structures, as well as offering explanatory and predictive tools and frameworks.

Theories in the social sciences differ fundamentally from those in the natural sciences because they address human behavior and social phenomena, which are complex, context-dependent, and influenced by myriad factors such as agency, culture, and history. While natural science theories often seek universal laws (e.g., Newton’s laws of motion or Darwin’s theory of natural selection), social science theories are typically more contingent and interpretive, aiming to explain patterns, relationships, and processes in human societies. However, the physical and natural sciences also involve contingency and interpretation. All sciences works both deductively and inductively.

Social science theories are derived from systematic observation, data analysis, and careful interpretation. Theories of social stratification, such as Max Weber’s analysis of class, status, and power, or Karl Marx’s theory of historical materialism, are rooted in empirical study and offer valuable insights into the dynamics of economic, political, and social systems. These theories are not universally deterministic, but rather provide robust tools for understanding complex social phenomena. They enjoy considerable degrees of criterion-related validity.

One of the key roles of theory in the social sciences is to provide frameworks for explaining why and how particular social phenomena occur. Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus, which explains how individual behaviors and perceptions are shaped by social structures and past experiences, illuminates the interplay between agency and structure, helping observers understand how societal norms and individual actions influence each other. Such theories deepen our understanding of social behavior and offer ways to analyze human interactions that would otherwise appear chaotic or random.

Unlike atoms or molecules, humans act within culturally, historically, and socially contingent frameworks that are constantly evolving. Theories in the social sciences embrace this complexity rather than reducing it to oversimplified models. Clifford Geertz’s interpretive anthropology emphasizes the importance of “thick description” in understanding cultural phenomena. This approach does not aim for universal generalizations but instead seeks a nuanced understanding of particular social contexts. Such theories allow researchers to engage deeply with the experiences of individuals and communities, offering insights that are both meaningful and practically relevant.

Theories in the social sciences also have predictive value, more probabilistic than the deterministic, but, again, this is true of the physical and natural sciences, as well. Criminological theories, such as strain theory, provide predictive insights into crime trends and patterns, which can inform policy and intervention strategies.

Critiques like Chomsky’s (Richard Feynman’s critique of sociology is another example) stem from comparing the social sciences to the natural and physical sciences without fully appreciating the unique nature of social phenomena. While it is true that social science theories may lack the precision and universal applicability of some natural science theories, this is a reflection of the subject matter rather than a shortcoming of the discipline. The social sciences grapple with the dynamic, fluid, and meaning-laden realm of human life, which requires theoretical frameworks that are flexible, interpretive, and responsive to context.

Theories in the social sciences are indispensable for understanding the complexities of human behavior and social systems. While they differ from the theories of natural sciences in their approach and scope, this difference is a strength, not a weakness. Social science theories provide crucial explanatory frameworks and offer practical tools for addressing societal challenges. Far from being a detriment to the intellectual landscape, the theoretical work of the social sciences enriches our understanding of the human condition and equips us to navigate an increasingly complex world.

This is not true of postmodernist literary theory. Its incorporation of theoretical language is pretentious. Postmodernist approaches employ dense and abstract terminology that can obscure meaning rather than clarify it. Unlike the empirically grounded and practically applicable theories in the social sciences, postmodernist theory avoids empirical engagement—even denying that universalism is possible since science itself is just another discourse. Postmodernists emphasize rhetorical style over explanatory power. It is more performative than substantive. The obscurantism inherent in such postmodernist “theories” as critical race theory and queer theory is not a bug but a feature. In fields serving the interests of corporate power, one should not expect otherwise.